Robert of Jumièges

Robert of Jumièges[lower-alpha 1] (died between 1052 and 1055) was the first Norman Archbishop of Canterbury.[1] He had previously served as prior of the Abbey of St Ouen at Rouen in Normandy, before becoming abbot of Jumièges Abbey, near Rouen, in 1037. He was a good friend and adviser to the king of England, Edward the Confessor, who appointed him bishop of London in 1044, and then archbishop in 1051. Robert's time as archbishop lasted only about eighteen months. He had already come into conflict with the powerful Earl Godwin and, while archbishop, made attempts to recover lands lost to Godwin and his family. He also refused to consecrate Spearhafoc, Edward's choice to succeed Robert as Bishop of London. The rift between Robert and Godwin culminated in Robert's deposition and exile in 1052.

Robert of Jumièges | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

| Appointed | 1051 |

| Term ended | September 1052 |

| Predecessor | Eadsige |

| Successor | Stigand |

| Other post(s) | Abbot of Jumièges Abbey Bishop of London |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 1044 |

| Personal details | |

| Died | between 1052 and 1055 Jumièges |

A Norman medieval chronicler[lower-alpha 2] claimed that Robert travelled to Normandy in 1051 or 1052 and told Duke William of Normandy that Edward wished for him to become his heir. The exact timing of Robert's trip, and whether he actually made it, have been the subject of debate among historians. The archbishop died in exile at Jumièges sometime between 1052 and 1055. Robert commissioned significant building work at Jumièges and was probably involved in the first Romanesque building in England, the church built in Westminster for Edward the Confessor, now known as Westminster Abbey. Robert's treatment by the English was used by William as one of the justifications for his invasion of England.

Background and life in Normandy

Robert was prior of the monastery of St Ouen at Rouen before he became abbot of the important Jumièges Abbey[4][5] in 1037.[2] Jumièges had been refounded under the Norman ruler William Longsword[6][7] around 940.[8] Its ties with the ducal family were close and it played a role in ducal government and church reform.[9] Robert's alternate surname "Champart" or "Chambert" probably derived from champart, a term for the part of a crop paid as rent to a landlord. Besides evidence that the preceding abbot at Jumièges was a relative, Robert's origin and family background are otherwise unknown. While abbot, Robert began construction of the abbey church, in the new Romanesque style.[2]

Robert became friendly with Edward the Confessor, a claimant to the English throne, while Edward was living in exile in Normandy, probably in the 1030s.[1] Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready, king of England, who had been replaced by Cnut the Great in 1016. Cnut subsequently married Æthelred's widow Emma of Normandy, Edward's mother, and had a son with her, Harthacanute. For their own safety, Edward and his brother Alfred were sent to Emma's relatives in Normandy.[10][lower-alpha 3] After Cnut's death in 1035, Harold Harefoot, his elder son by his first wife, acceded to the English throne. Following Harald's death in 1040, Harthacanute succeeded him for a short time, but as neither Harald nor Harthacanute left offspring, the throne was offered to Edward on Harthacanute's death in 1042.[12] There is some evidence that Edward spent some of his time in exile around Jumièges, as after becoming king he gave gifts to the abbey.[13]

Bishop and archbishop

Robert accompanied Edward the Confessor on Edward's recall to England in 1042[1] to become king following Harthacanute's death.[2] It was due to Edward that in August 1044 Robert was appointed Bishop of London,[14] one of the first episcopal vacancies which occurred in Edward's reign.[15] Robert remained close to the king and was the leader of the party opposed to Earl Godwin, Earl of Wessex.[2] Godwin, for his part, was attempting to expand the influence of his family, which had already acquired much land. His daughter was Edward's queen, and two of his sons were elevated to earldoms.[16] The Life of Saint Edward, a hagiographical work on King Edward's life, claimed that Robert "was always the most powerful confidential adviser of the king".[17] Robert seems to have favoured closer relations with Normandy, and its duke.[15] Edward himself had grown up in the duchy, and spent 25 years in exile there before his return to England. He brought many Normans with him to England, and seems to have spent much time in their company.[18]

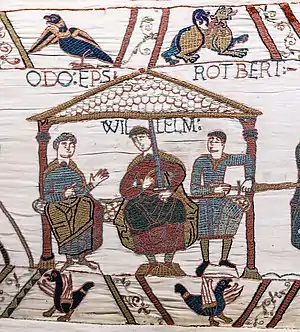

When Archbishop Eadsige of Canterbury died in October 1050,[19] the post remained vacant for five months.[2] The cathedral chapter elected Æthelric, a kinsman of Godwin and a monk at Canterbury,[20][21] but were over-ruled when Edward appointed Robert Archbishop of Canterbury the following year.[2][22] Godwin was attempting to exercise his power of patronage over the archbishopric, but the king's appointment signalled that the king was willing to contest with the earl over the traditional royal rights at Canterbury.[23] Although the monks of Canterbury opposed it, the king's appointment stood.[24] Robert went to Rome to receive his pallium and returned to England[25] where he was ceremonially enthroned at Canterbury on 29 June 1051.[2] Some Norman chroniclers state that he visited Normandy on this trip and informed Duke William the Bastard that he was the childless King Edward's heir.[15] According to these chroniclers, the decision to make William the heir had been decided at the same lenten royal council in 1051 that had declared Robert archbishop.[2]

After returning from Rome, Robert refused to consecrate Spearhafoc, the Abbot of Abingdon and the king's goldsmith,[26] as his successor to the bishopric of London, claiming that Pope Leo IX had forbidden the consecration. Almost certainly the grounds were simony,[27] the purchase of ecclesiastical office,[28] as Leo had recently issued proclamations against the practice. In refusing to consecrate Spearhafoc, Robert may have been following his own interests against the wishes of both the king and Godwin, as he had his own candidate, a Norman, in mind.[27] In the end Robert's favoured candidate, William the Norman, was consecrated instead of Spearhafoc.[2][26] Robert also discovered that some lands belonging to Canterbury had fallen into Godwin's hands, but his efforts to recover them through the shire courts were unsuccessful.[27] Canterbury had lost control of some revenues from the shire of Kent to Godwin during Eadsige's tenure as archbishop, which Robert unsuccessfully attempted to reclaim.[29] These disputes over the estates and revenues of the archbishopric contributed to the friction between Robert and Godwin,[29][30] which had begun with Robert's election. Robert's election had disrupted Godwin's patronage powers in Canterbury, and now Robert's efforts to recover lands Godwin had seized from Canterbury challenged the earl's economic rights.[23] Events came to a head at a council held at Gloucester in September 1051, when Robert accused Earl Godwin of plotting to kill King Edward.[31][lower-alpha 4] Godwin and his family were exiled; afterwards Robert claimed the office of sheriff of Kent, probably on the strength of Eadsige, his predecessor as archbishop, having held the office.[33]

Although Robert refused to consecrate Spearhafoc, there is little evidence that he was interested in the growing movement towards Church reform being promulgated by the papacy.[34] Pope Leo IX was beginning a reform movement later known as the Gregorian Reform, initially focused on improving the clergy and prohibiting simony. In 1049 Leo IX declared that he would take more interest in English church matters and would investigate episcopal candidates more strictly before confirming them. It may have been partly to appease Leo that Edward appointed Robert instead of Æthelric, hoping to signal to the papacy that the English crown was not totally opposed to the growing reform movement.[35] It was against this backdrop that Robert refused to consecrate Spearhafoc, although there is no other evidence that Robert embraced the reform position, and his claim that the pope forbade the consecration may have had more to do with finding an easy excuse than any true desire for reform.[34] There are also some indications that Spearhafoc was allied to Godwin, and his appointment was meant as a quid pro quo for the non-appointment of Æthelric.[19][36] If true, Robert's refusal to consecrate Spearhafoc would have contributed to the growing rift between the archbishop and the earl.[19]

Royal adviser

The Life of Saint Edward claims that while Godwin was in exile Robert tried to persuade King Edward to divorce Edith, Godwin's daughter, but Edward refused and instead she was sent to a nunnery.[33] However, the Life is a hagiography, written soon after Edward's death to show Edward as a saint. Thus it stresses that Edward voluntarily remained celibate, something unlikely to have been true and not corroborated by any other source. Modern historians have felt it more likely that Edward, at Robert's urging, wished to divorce Edith and remarry to have children to succeed him on the English throne,[37] although it is possible that he merely wished to be rid of her, without necessarily wanting a divorce.[2]

During Godwin's exile, Robert is said to have been sent by the king on an errand to Duke William of Normandy.[38] The reason for the embassy is uncertain. William of Jumièges says that Robert went to tell Duke William that Edward wished William to be his heir. The medieval writer William of Poitiers gives the same reason, but also adds that Robert took with him as hostages Godwin's son Wulfnoth and grandson Hakon (son of Sweyn). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is silent on the visit however, so it is uncertain whether Robert visited Normandy or not, or why he did so.[39] The entire history of the various missions which Robert is alleged to have made is confused, and complicated by propaganda claims made by Norman chroniclers after the Norman Conquest in 1066,[35][40][lower-alpha 5] leaving it unclear if Robert visited Normandy on his way to receive his pallium or after Godwin was in exile, or if he went twice or not at all.[35][41][42]

Outlawing, death, and legacy

After Godwin left England, he went to Flanders, and gathered a fleet and mercenaries to force the king to allow his return. In the summer of 1052, Godwin returned to England and was met by his sons, who had invaded from Ireland. By September, they were advancing on London, where negotiations between the king and the earl were conducted with the help of Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester.[43] When it became apparent that Godwin would be returning, Robert quickly left England[44] with Bishop Ulf of Dorchester and Bishop William of London, probably once again taking Wulfnoth and Hakon with him as hostages, whether with the permission of King Edward or not.[45][lower-alpha 6] Robert was declared an outlaw and deposed from his archbishopric on 14 September 1052 at a royal council, mainly because the returning Godwin felt that Robert, along with a number of other Normans, had been the driving force behind his exile.[22][44][lower-alpha 7] Robert journeyed to Rome to complain to the pope about his own exile,[48] where Leo IX and successive popes condemned Stigand,[49] whom Edward had appointed to Canterbury.[50] Robert's personal property was divided between Earl Godwin, Harold Godwinson, and the queen, who had returned to court.[51]

Robert died at Jumièges,[52] but the date of his death is unclear. Various dates are given, with Ian Walker, the biographer of Harold arguing for between 1053 and 1055,[39] but H. E. J. Cowdrey, who wrote Robert's Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry, says on 26 May in either 1052 or 1055.[2][lower-alpha 8] H. R. Loyn, another modern historian, argues that it is likely that he died in 1053.[53]

Robert's treatment was used by William as one of the justifications for his invasion of England, the other being that Edward had named William his heir. Ian Walker, author of the most recent scholarly biography of Harold Godwinson, suggests that it was Robert, while in exile after the return of Godwin, who testified that King Edward had nominated Duke William to be Edward's heir.[49] However, this view is contradicted by David Douglas, a historian and biographer of William the Conqueror, who believes that Robert merely relayed Edward's decision, probably while Robert was on his way to Rome to receive his pallium.[4] Several medieval chroniclers, including the author of the Life of Saint Edward, felt that the blame for Edward and Godwin's conflict in 1051–1052 lay squarely with Robert;[54] modern historians tend to see Robert as an ambitious man, with little political skill.[2]

Artistic patronage

In notable contrast to his successor Stigand, Robert does not figure among the important benefactors to English churches,[55] but we know of some transfers to Jumièges of important English church treasures, the first trickle of what was to become a flood of treasure taken to Normandy after the Conquest.[56] These included the relic of the head of Saint Valentine only recently given to the monks of Winchester Cathedral by Emma of Normandy. Though the Winchester head remained in place, another one appeared at Jumièges; he "must have clandestinely removed the head, or at least the greater part of it, and left his monks to venerate the empty or nearly empty capsa".[57] Two of the four most important surviving late Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts went the same way,[lower-alpha 9] thus probably preventing their destruction in a series of fires that devastated the major English libraries.[59] One is the so-called Missal of Robert of Jumièges, actually a sacramentary with thirteen surviving full-page miniatures, which bears an inscription apparently in Robert's own hand recording its donation to Jumièges when he was Bishop of London,[58] and the other the so-called Benedictional of Archbishop Robert, actually a pontifical with three remaining full-page miniatures and other decoration (respectively Rouen, Bibliothèque Municipale, Manuscripts Y.6 and Y.7). The latter may well have been commissioned by Æthelgar, Robert's predecessor as archbishop in 988–90, although it is possible the "Archbishop Robert" of the traditional name is Emma's brother Robert, Archbishop of Rouen from 990 to 1037.[60][61][lower-alpha 10] These masterpieces of the Winchester style were the most elaborately decorated Anglo-Saxon manuscripts known to have reached Normandy, either before or after the Conquest, and influenced the much less-developed local style, though this remained very largely restricted to initials.[63]

Before he came to England, Robert had begun the construction of a new abbey church at Jumièges, in the new Romanesque style which was then becoming popular,[64] and introduced to Normandy the two-towered western facade from the Rhineland. On his return to Normandy he continued to build there,[65] and the abbey church was not finished until 1067.[66] Although the choir has been torn down, the towers, nave and transepts have survived.[67] Robert probably influenced Edward the Confessor's rebuilding of the church at Westminster Abbey, the first known building in the Romanesque style in England, which is so described by William of Malmesbury.[64][68] Edward's work began in about 1050 and was completed just before his death in 1065. The recorded name of one of the senior masons, "Teinfrith the churchwright" indicates foreign origins, and Robert may have arranged for Norman masons to be brought over, though other names are English.[69] It is possible that Westminster influenced the building at Jumièges, as the arcade there closely resembles Westminster's arcade, both of them in a style that never became common in Normandy.[70] The Early Romanesque style of both was to be superseded after the Conquest by the Anglo-Norman High Romanesque style pioneered in Canterbury Cathedral and St Étienne, Caen by Lanfranc.[71]

Notes

- Sometimes known as Robert Chambert or Robert Champart.

- This refers to William of Jumièges who does not appear to be a relation to Robert. Both gained the surname by being monks at Jumièges.[2][3]

- Both Alfred and Edward returned to England in 1036, but afterwards Alfred was murdered, apparently on Harold's orders.[11]

- Godwin was especially vulnerable to this charge, as he had been involved in the death of Edward's brother Alfred during Harthacanute's reign.[32]

- The whole issue is discussed in John "Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession" English Historical Review, and Oleson "Edward the Confessor's Promise of the Throne" English Historical Review, listed in the references, where the various theories are set forth in great detail.

- Ulf never returned to England, but William was allowed to return eventually.[46]

- Edith, after her father's restoration to power, was returned to court and reinstated as queen.[47]

- Note that May 1052 is probably wrong, as it is prior to the September 1052 date when, according to most historians, Robert fled England.[2][39][53]

- The other two being the Benedictional of St Aethelwold and the Harley Psalter, according to D. H. Turner.[58]

- The inscription naming it as a gift of "Archbishop Robert" dates from the 17th century and is not clear which Archbishop Robert is being referred to.[62]

Citations

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 50

- Cowdrey "Robert of Jumièges" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- van Houts, Elizabeth "William of Jumièges" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Douglas William the Conqueror p. 167–170

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 44

- Crouch Normandy Before 1066 p. 30

- Crouch Normans p. 12

- Crouch Normandy Before 1066 p. 58

- Crouch Normandy Before 1066 pp. 193–194

- Hindley Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons pp. 306–310

- Hindley Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons pp. 316–317

- Hindley Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons pp. 315–318

- Crouch Normans p. 78

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 230

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 pp. 46–50

- Mason House of Godwine pp. 51–53

- Quoted in Huscroft Ruling England p. 50

- Potts "Normandy" Companion to the Anglo-Norman World p. 33

- Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England pp. 128–129

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 104

- Walker Harold p. 27

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 214

- Bates "Land Pleas of William I's Reign" Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research p. 16

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 209

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 106

- Huscroft Ruling England p. 52

- Walker Harold p. 29–30

- Coredon Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases p. 260

- Rex Harold II pp. 42–43

- Campbell "Pre-Conquest Norman Occupation of England" Speculum p. 22

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 111

- Barlow Godwins p. 42

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 115

- Rex Harold II p. 46

- Stafford Unification and Conquest pp. 89–92

- John Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England p. 177

- Walker Harold p. 35–36

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 107

- Walker Harold p. 37–38

- Bates William the Conqueror p. 73

- John "Edward the Confessor" English Historical Review

- Oleson "Edward the Confessor" English Historical Review

- Mason House of Godwine pp. 69–75

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 124

- Walker Harold p. 47

- Rex Harold II p. 12

- Mason House of Godwine p. 75

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 126

- Walker Harold p. 50–51

- Stafford Unification and Conquest p. 94

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 568

- Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England p. 137

- Loyn English Church p. 59

- Stafford Queen Emma and Queen Edith p. 11

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art mentions many of these, but not Robert.

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art pp. 216–222 and passim

- Kelly Chaucer p. 54

- Turner "Illuminated Manuscripts" Golden Age p. 69

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art pp. 224–225

- Turner "Illuminated Manuscripts" Golden Age p. 60

- Gameson "Winchester School" Blackwell Encyclopaedia p. 482

- Lawrence "Anglo-Norman Book Production" England and Normandy p. 83

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art pp. 225–226

- Mason House of Godwine p. 83

- Gem "Origins" Westminster Abbey p. 15

- Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England p. 148

- Plant "Ecclesiastical Architecture" Companion to the Anglo-Norman World pp. 219–222

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 51 footnote 2

- Gem "Origins" Westminster Cathedral pp. 13–15

- Breese "Early Normandy and the Emergence of Norman Romanesque Architecture" Journal of Medieval History p. 212

- Gem "English Romanesque Architecture" English Romanesque Art p. 26

References

- Barlow, Frank (1970). Edward the Confessor. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01671-8.

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1000–1066: A History of the Later Anglo-Saxon Church (Second ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49049-9.

- Barlow, Frank (2003). The Godwins: The Rise and Fall of a Noble Dynasty. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-78440-9.

- Bates, David (May 1978). "The Land Pleas of William I's Reign: Penenden Heath Revisited". Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. LI (123): 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1978.tb01962.x.

- Bates, David (2001). William the Conqueror. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1980-3.

- Breese, Lauren Wood (1988). "Early Normandy and the Emergence of Norman Romanesque Architecture". Journal of Medieval History. 14 (3): 203–216. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(88)90003-6.

- Campbell, Miles W. (January 1971). "A Pre-Conquest Norman Occupation of England". Speculum. 46 (1): 21–31. doi:10.2307/2855086. JSTOR 2855086. S2CID 162235772.

- Coredon, Christopher (2007). A Dictionary of Medieval Terms & Phrases (Reprint ed.). Woodbridge, UK: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-138-8.

- Cowdrey, H. E. J. (2004). "Robert of Jumièges (d. 1052/1055)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23717. Retrieved 10 November 2007. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Crouch, David (1982). Normandy Before 1066. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-48492-8.

- Crouch, David (2007). The Normans: The History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN 978-1-85285-595-6.

- Dodwell, C.R (1982). Anglo-Saxon Art, A New Perspective. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0926-X.

- Douglas, David C. (1964). William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. OCLC 399137.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third Edition, revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Gameson, Richard (2001). "Winchester School". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donal (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 482–484. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Gem, Richard (1984). "English Romanesque Architecture". In Zarnecki, George; et al. (eds.). English Romanesque Art, 1066–1200. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. OCLC 12480908.

- Gem, Richard (1986). "The Origins of the Abbey". In Wilson, Christopher; et al. (eds.). Westminster Abbey. London: Bell and Hyman. OCLC 13125790.

- Higham, Nick (2000). The Death of Anglo-Saxon England. Stroud, UK: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-2469-1.

- Hill, Paul (2005). The Road to Hastings: The Politics of Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3308-3.

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2006). A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons: The Beginnings of the English Nation. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1738-5.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- John, Eric (April 1979). "Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession". The English Historical Review. 96 (371): 241–267. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXXI.241. JSTOR 566846.

- John, Eric (1996). Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5053-7.

- Kelly, Henry Ansgar (1986). Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-07849-5.

- Lawrence, Anne (1994). "Anglo-Norman Book Production". In Bates, David; Curry, Anne (eds.). England and Normandy in the Middle Ages. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 80–93. ISBN 1-85285-083-3.

- Loyn, H. R. (2000). The English Church, 940–1154. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-30303-6.

- Mason, Emma (2004). House of Godwine: The History of Dynasty. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN 1-85285-389-1.

- Oleson, T. J. (April 1957). "Edward the Confessor's Promise of the Throne to Duke William of Normandy". The English Historical Review. 72 (283): 221–228. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXII.CCLXXXIII.221. JSTOR 558704.

- Plant, Richard (2002). "Ecclesiastical Architecture c.1050 to c.1200". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; van Houts, Elizabeth (eds.). A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 215–253. ISBN 978-1-84383-341-3.

- Potts, Cassandra (2002). "Normandy, 911–1144". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; van Houts, Elizabeth (eds.). A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 19–42. ISBN 978-1-84383-341-3.

- Rex, Peter (2005). Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7394-7185-2.

- Stafford, Pauline (1997). Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women's Power in Eleventh-century England. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-22738-5.

- Stafford, Pauline (1989). Unification and Conquest: A Political and Social History of England in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-6532-4.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Turner, D.H (1984). "Illuminated Manuscripts: Part II, The Golden Age". In Backhouse, Janet; Turner, D.H.; Webster, Leslie (eds.). The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art, 966–1066. British Museum Publications. OCLC 11211909.

- van Houts, Elizabeth (2004). "Jumièges, William of (fl. 1026–1070)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54418. Retrieved 30 September 2008. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Walker, Ian (2000). Harold the Last Anglo-Saxon King. Gloucestershire, UK: Wrens Park. ISBN 0-905778-46-4.

Further reading

- Gem, R. D. H. (1980). "The Romanesque rebuilding of Westminster Abbey". Anglo-Norman Studies. Vol. 3. pp. 33–60. or his collected papers