Robert Fassnacht

Robert E. Fassnacht (January 14, 1937 – August 24, 1970) was an American physics post-doctoral researcher who was killed by the August 1970 bombing of Sterling Hall on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, perpetrated as a protest against the Vietnam War.[2][3]

Robert Fassnacht | |

|---|---|

| Born | January 14, 1937 |

| Died | August 24, 1970 (aged 33) |

| Cause of death | Bomb explosion |

| Alma mater | Kalamazoo College University of Wisconsin–Madison |

| Occupation | Physics researcher |

| Spouse | Stephanie Fassnacht |

| Children | Christopher, Heidi and Karin |

| Parent | Walter Fassnacht[1] |

Fassnacht was a student from South Bend, Indiana, who received a Westinghouse scholarship to attend college.[4] He was at the University of Wisconsin–Madison pursuing post-doctoral research in the field of superconductivity.

Bombing

On the night of August 23 and into the early morning hours of August 24, 1970, Fassnacht was in the lab taking care of unfinished work because he and his family were slated to leave for a vacation in San Diego, California. His lab was located in the basement of Sterling Hall. He was in the process of cooling down his dewar with liquid nitrogen when the explosion occurred. Rescuers found him face down in about a foot of water. The cause of death, determined from the autopsy, was internal trauma.

As a protest against the Vietnam War, the bomb was built and planted by Karleton "Karl" Armstrong, Dwight Armstrong, David Fine, and Leo Burt. The intention was to destroy the Army Mathematics Research Center, but instead destroyed much of the physics department and severely damaged neighboring buildings.[5]

After the bombing

Family

Fassnacht was survived by his wife, Stephanie, and their three children, a three-year-old son, Christopher, and twin daughters, Heidi and Karin who turned one a month after their father's death.[2] The family continued to live in Madison in relative quiet and anonymity for many decades after the explosion, often crossing paths with the site of their father/husband's murder.

Stephanie Fassnacht completed a long career at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, occupying an office just blocks from the site of her husband's death. She stated that she harbored "no ill will" toward Karl Armstrong "and never did."[6] Instead she held the Board of Regents responsible.[7] Christopher attended Harvard University and Caltech and is now a physics professor at the University of California at Davis.[8] Heidi and Karin both graduated from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

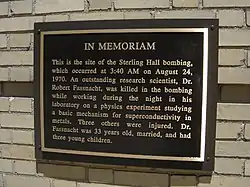

Commemorative plaque

On May 18, 2007, the University of Wisconsin–Madison unveiled a plaque on the side of Sterling Hall commemorating the bombing and Robert Fassnacht's death. The event was attended by John D. Wiley, then Chancellor of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and an acquaintance of Robert Fassnacht, by current and former members of the Physics department, including chair Susan Coppersmith, and family and friends of Robert, including his daughters Heidi and Karin.[9][10][11]

The plaque reads:

IN MEMORIAMThis is the site of the Sterling Hall Bombing, which occurred at 3:40 AM on August 24, 1970. An outstanding research scientist, Dr. Robert Fassnacht, was killed in the bombing while working in his laboratory on a physics experiment studying a basic mechanism for superconductivity in metals. Three others were injured. Dr. Fassnacht was 33 years old, married, and had three young children.

Bibliography

- Fassnacht, R. E.; Dillinger, J. R. (1967-08-01). "Superconductivity of Cd–Bi Eutectic Solder". Journal of Applied Physics. 38 (9): 3667–3668. doi:10.1063/1.1710191. ISSN 0021-8979.

- Fassnacht, R. E.; Dillinger, J. R. (1967-08-08). "Time Mark Generator for an X‐Y Recorder". Review of Scientific Instruments. 39 (1): 127. doi:10.1063/1.1683090. ISSN 0034-6748.

- Fassnacht, R. E.; Dillinger, J. R. (1967-12-10). "Superconducting Transitions of Isotopes of Zinc". Physical Review. 164 (2): 565–574. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.164.565.

- Dillinger, J. R.; Fassnacht, R. E.; Jones, D. M. (1968-10-31). "Isotope Effect in Zinc and Zirconium". OSTI 4507358.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Fassnacht, R. E.; Dillinger, J. R. (1969-03-10). "Isotope Effect in Superconducting Gallium". Physics Letters A. 28 (11): 741–742. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(69)90595-7. ISSN 0375-9601.

- Fassnacht, R. E.; Dillinger, J R. (1970-05-11). "Evidence for Fluctuation Effects above TC in Isotopically and Metallurgically Pure Bulk Type-I Superconductors". Physical Review Letters. 24 (19): 1059–1061. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.24.1059.

- Fassnacht, R. E.; Dillinger, J. R. (1970-12-01). "Isotope Effect in Superconducting Cadmium". Physical Review B. 2 (11): 4442–4444. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.2.4442.

References

- Fathers cope with sons' bomb death, jailing United Press International

- Dillinger, Joseph R. (October 1970). "Obituary: Robert E. Fassnacht". Physics Today. 23 (10): 69. doi:10.1063/1.3021801.

- Ziff, Deborah; Seely, Ron (17 August 2010). "Sterling Hall bombing: 40 years later, family members celebrate physicist's life". Wisconsin State Journal. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018.

On Aug. 24, 1970, four young men, angry about the war in Vietnam, drove up to Sterling Hall in the middle of the night to bomb the Army Mathematics Research Center on the building's upper floors. They parked their Econoline van and lit a fuse, not thinking anyone was inside. Neither a soldier nor a radical, Fassnacht was caught in the crossfire.

- Doug Moe: Chicago's other great columnist by Doug Moe, July 2, 2004, The Capital Times

- Durhams, Sharif; Maller, Peter (19 August 2000). "30 years ago, bomb shattered UW campus". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- Ziff, Deborah (22 May 2012). "On Campus: Stephanie Fassnacht tells CBS: "no ill will" toward Karl Armstrong over Sterling Hall bombing". Wisconsin State Journal. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-29.

Fassnacht and her family have largely avoided the media in an effort to move on with their lives

- Bingham, Clara (April 2017). Witness to the Revolution. Random House Publishing Group. p. 485. ISBN 9780812983265.

- "Christopher Fassnacht". UC Davis, Department of Physics. Archived from the original on 13 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Memorial Plaque Honors Fassnacht by Katie Dean, The Capital Times

- Fassnacht, Heidi (24 August 2011). "Reflections on Sterling Hall, a thank-you for opening your hearts". The Capital Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- LaRoi, Heather (18 May 2007). "PLAQUE TO BE DEDICATED FOR 1970 STERLING HALL BOMBING". The Capital Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

Books and Resources

- Rads: The 1970 Bombing of the Army Math Research Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Its Aftermath, 1992, by Tom Bates (ISBN 0060167548)

- The Madison Bombings, 1988, by Michael Morris (ISBN 0947002308)

- Madison Newspapers Archive of the Sterling Hall Bombing

- Dillinger, Joseph R. (2008-12-30). "Robert E. Fassnacht". Physics Today. 23 (10): 69. doi:10.1063/1.3021801. ISSN 0031-9228.

- "STERLING HALL/MATH RESEARCH CENTER BOMBING FINDING AID" (PDF). UW Archives. 12 February 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

The bombing of Sterling Hall on the morning of August 24, 1970 was one of the pivotal events of the protest movements of the 1960s and 70s, as well as in the history of the University of Wisconsin's Madison campus. [...] this research guide has been compiled with the aim of aiding those inquiring into the bombing.

- Reeves, Troy (ed.). "Sterling Hall Bombing of 1970 | Oral History Website". University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- Crandell, Marlene, ed. (2009) [1957]. The Kalamazoo College Boiling Pot (PDF). Kalamazoo, Michigan: Kalamazoo College Archives. pp. 32, 33, 66, 67. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- "91st Congress, 2nd Session - SENATE; ILLEGAL TRANSPORTATION, USE, OR POSSESSION OF EXPLOSIVES" (PDF). Congressional Record. 116, Part 26 (October 1, 1970 to October 8, 1970): 35630. 8 October 1970.

Senator McClellan: Robert Fassnacht lost his life at the University of Wisconsin in Madison when a terrorist bomb, aimed at [the] Army-funded mathematics center on the second and fourth floors of the building, demolished the physics lab below. Lost, too, was the life's work of Prof. Joseph R. Dillinger, who has spent the last 23 years constructing, step by painful step, an intricate assemblage of cryogenic machinery, which was totally wiped out by the blast. Faced with this destruction of his own life's work, Dillinger, according to Life magazine-September 18, 1970, at page 41, column 3-is bewildered and bitter. "Fassnacht is dead and nothing can bring him back," he says. "That's the biggest loss of all. As for my lab, I could rebuild it all for about $150,000 (equivalent to $1,130,000 in 2022). It would take me about 6 years, but I could do it. But by then I'd be 60. And suppose they blew it up again? What's the point?"