Rio Grande marine ecoregion

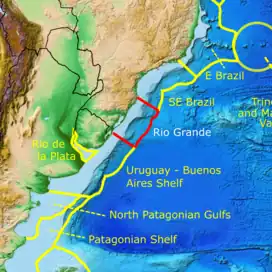

The Rio Grande marine ecoregion covers the waters offshore of the southern Brazilian states of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. The ecoregion stretches along 500 miles of sandy beach coast, and 200 miles out to sea. The warm Brazil Current flows south through the region in parallel with the coast. The continental shelf is smooth and flat, with the bottom mostly sand and mud. Overfishing is a problem, but marine life in recent years has benefited from measures such as a 2018 ban on motorized shrimp trawler fishing within 12 miles of the Rio Grande do Sul coast. The Rio Grande ecoregion is one of four coastal marine ecoregions in the Warm Temperate Southwestern Atlantic marine province. It is thus part of the Temperate South America realm. [1] [2] [3] .[4]

| Rio Grande marine ecoregion | |

|---|---|

Parque da Guarita, Torres, Brazil | |

Marine ecoregion boundaries (red line) | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Temperate South America |

| Province | Warm Temperate Southwestern Atlantic |

| Borders (marine) | Southeastern Brazil marine ecoregion, Uruguay - Buenos Aires Shelf marine ecoregion |

| Geography | |

| Country | Brazil |

Physical setting

The ecoregion is bounded on the north at Florianopolis (latitude 28°S), and on the south at the border with Uruguay (latitude 34°S), where the ecoregion transitions to the Uruguay - Buenos Aires Shelf marine ecoregion. Together the two ecoregions make up the South Brazil Shelf, a Large Marine Ecosystem (LME). The bordering coast is generally low-lying coastal scrub and sand in a long barrier island fronting a chain of lakes and lagoons. The terrestrial ecoregion on-shore is the Uruguayan savanna ecoregion.[5] There are no major rivers feeding directly into the ocean in the ecoregion.

A significant feature of the Rio Grande marine ecoregion is the inclusion of an inland lagoon - Lagoa dos Patos, the largest coastal lagoon in South America. The 150 mile long lagoon is separated from the ocean by a 5-10 mile wide sand bar, and is open to the sea at an opening at the city of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul. Just south of Lagoa dos Patos is Lagoon Mirim, which is cut off from the sea.

The continental shelf along this coast of Brazil extends an average of 200 km out to sea before dropping off. The deepest point in the ecoregion overall is −1,054 metres (−3,458 ft), and the average is −84 metres (−276 ft).[2]

Currents and climate

The Brazil Current (BC) flows south through the ecoregion, parallel to the coast.[6] The Brazil Current flows at a transport rate averaging 11 Sverdrups (Sv) as it enters the region in the north, building to 22 Sv as the current leaves the region in the south. It moves at a mean speed of 60–100 centimetres per second (1.3–2.2 mph). Surface temperatures range from 18–28 °C (64–82 °F), but vary by 5-13 18–28 °C (64–82 °F), with the warmer temperatures in August and further inshore.[6] The BC is a western boundary current, the southern hemisphere counterpart of the Gulf Stream, but shallower and weaker.[6] There is some evidence that the BC may be shifting slightly southward due to the influence of surface warming hotspots.[7]

Animals / Fish

The marine life of the region is influenced by the convergence of the south-flowing Brazil Current and the north-flowing Malvinas Current south of the ecoregion.[8] The nutrients of the currents plus continental runoff support high biological production in the lagoons and on the continental shelf. Commercial fisheries exist for shrimp, weakfish, mullet, sardines, anchovies, and, offshore, shark and tuna.[9][10] The lagoon complexes support pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus paulensis) (São Paulo shrimp) and southern white shrimp (Litopenaeus schmitti).[11]

One study in the 1990s found that 80% of the biomass on the shelf were teleost (ray-finned) fish species of the family (Sciaenidae) (drums and croaker). Many of the fish are seasonal, coming from the colder, more nutrient-rich waters to the south. The commercially important seasonal fish include the striped (Argentine) croaker (Umbrina canosai), weakfish (Cynoscion guatucupa), croaker (Micropogonias furnieri), red porgy (Pagrus pagrus) and school shark (Galeorhinus galeus). These migrant fish account for 70% of the catch in the ecoregion.[9]

Because the bottom in the region features flat, smooth, and shallow waters, it is in important breeding ground for species such as rays and sharks. But the high levels of shrimp trawling, which uses tight nets, led to destructive levels of bycatch and disturbance of the sand and mud bottom. In 2018, overfishing led to a ban on trawler fishing out to 12 miles from the coast of the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The result has been a comeback for depleted species.[12]

Conservation status

Only about 0.4% of the ecoregion is in an officially protected area, including:[2]

- Área de Proteção Ambiental da Baleia Franca, in Santa Catarina state.

- Reserva Particular Do Patrimônio Natural Estadual Barba

References

- Spalding, MD; Fox, Helen; Allen, Gerald; Davidson, Nick. "Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas". Bioscience. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Rio Grande". Digital Observatory for Protected Areas (DOPA). Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- "Rio Grande". MarineRegions.org. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- "South Brazil Shelf". One Shared Ocean. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- "Setting Geographic Priorities for Marine Conservation in Latin America and the Caribbean" (PDF). The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- "Brazil Current". University of Miami. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- Bárbara Cristie Franco; Vincent Combes; Victoria González Carman (2020). "Subsurface Ocean Warming Hotspots and Potential Impacts on Marine Species: The Southwest South Atlantic Ocean Case Study". Frontiers in Marine Science. Frontier in Marine Science. 7. doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.563394. hdl:11336/143909.

- Marcelo Vasconcellosa; Maria A. Gasalla. "Fisheries catches and the carrying capacity of marine ecosystems in southern Brazil". Fisheries Research (2001). Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "Present state and perspectives for the southern Brazil shelf demersal fisheries" (PDF). Fisheries Management and Ecology (1998). Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- J. P. Castello; P. S. Sunye; M. Haimovici; D. Hellebrandt. "Fisheries in southern Brazil: a comparison of their management and sustainability". Journal of Applied Ichthyology. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles - Brazil". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "Fish return to Southern Brazil after trawling ban". Mongabay. 19 September 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2023.