Rio Grande do Sul Revolt of 1924

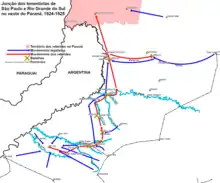

The Rio Grande do Sul Revolt of 1924 was triggered by tenentist rebels from the Brazilian Army and civilian leaders from the Liberating Alliance on 28–29 October of that year. The civilians, continuing the 1923 Revolution, wanted to remove the governor of Rio Grande do Sul, Borges de Medeiros, while the military were against the president of Brazil, Artur Bernardes. After a series of defeats, in mid-November the last organized stronghold was in São Luiz Gonzaga. In the south, guerrilla warfare continued until the end of the year. From São Luiz Gonzaga, the remnants of the revolt headed out of the state, joining other rebels in the Paraná Campaign and forming the Miguel Costa-Prestes Column.

| Rio Grande do Sul Revolt of 1924 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Tenentism | |||||||

Loyalist defenses in Itaqui | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Rebels

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

The "liberators" were the opposition to the hegemony of the Rio-Grandense Republican Party (PRR) in the state's politics. Their alliance with tenentism, a movement of national aspirations, was circumstantial. The tenentists' military authority, general Isidoro Dias Lopes, and the "civilian leader of the revolution", Joaquim Francisco de Assis Brasil, were not in Rio Grande do Sul. The operations were in charge of young officers trained in military science, like Juarez Távora, Siqueira Campos and Luís Carlos Prestes, and veteran leaders of Rio Grande do Sul's military tradition, such as Honório Lemes and Zeca Neto. Their enemies also combined regular units, the loyalists of the army and the Military Brigade, and irregulars, the "provisionals" (provisórios). Several PRR politicians, such as Osvaldo Aranha and Flores da Cunha, commanded government forces.

As in other conflicts in Rio Grande do Sul, cavalry was widely used and the temporary exile of rebels abroad was normal and commonplace. The initial uprisings were in Uruguaiana, São Borja, São Luiz Gonzaga and Santo Ângelo. Civilian and military governors were installed in the first three cities; their most controversial measures were the requisitions of goods and money. The rebels went on the offensive, but were unable to take Itaqui, whose loyalist garrison separated their territories. To the east, they were repelled when they tried to progress towards Ijuí and Alegrete and suffered a major defeat at Guaçu-Boi, on 9 November. In the south, the rebels continued a guerrilla campaign until their definitive expulsion to Uruguay; the last border incursion was in January 1925.

In the Missões region, the rebels concentrated in São Luiz Gonzaga, where captain Luís Carlos Prestes was designated commander in a letter from general Isidoro. The loyalists set up an "iron ring" of seven columns, in full numerical superiority, around the city. Prestes had to escape the siege to join the other rebels in Paraná, and in the process, the Prestes Column, as it would be known, began to take shape and employ its characteristic war of movement. The battle in Ramada, on 3 January, was the most violent in this phase. At the end of the month, the rebels entered Santa Catarina, and in April they joined the remnants of the revolt in São Paulo in Paraná. A community of exiles remained abroad, launching new revolts in 1925 and 1926. There is no consensus on the initial landmark of the Prestes Column (São Paulo, Santo Ângelo, São Luiz or Paraná). The memory of the revolt in Rio Grande do Sul today has its most notable public commemoration in Santo Ângelo.

Background

Rio Grande do Sul and Brazil's politics

The governments of Brazil and Rio Grande do Sul were respectively headed by Artur Bernardes and Borges de Medeiros in 1924. The relationship between the two, and their oppositions, was complex. In the 1922 presidential election, Medeiros supported the opposition Republican Reaction ticket against Bernardes' candidacy for the federal government. Conversely, the Rio Grande do Sul opposition supported Bernardes, who won the election.[1] To prevent Bernardes' inauguration, army officers began the July 1922 uprisings. They were quickly suppressed, but they inaugurated a movement opposing Brazil's Old Republic, tenentism. New revolts continued to be organized in the barracks.[2]

Bernardes' victory weakened the relationship between the federal government and the Rio-Grandense Republican Party (PRR), hegemonic in Rio Grande do Sul's politics. The dominant groups were ousted in the other states that supported the Republican Reaction (Bahia, Pernambuco and Rio de Janeiro), and the threat of federal intervention hovered in Rio Grande do Sul.[3][4] Borges de Medeiros was re-elected for a fifth time at the end of 1922, but the opposition, led by Joaquim Francisco de Assis Brasil, contested the results and initiated a civil war in 1923. The "assististas" were outnumbered, but expected federal support. When it did not come, they were forced to negotiate peace.[1] Meanwhile, in the middle of the civil war, general Isidoro Dias Lopes, future commander of the revolt in São Paulo, was in Rio Grande do Sul contacting opposition leaders.[5]

The army, represented in the state by the 3rd Military Region, remained neutral during the conflict, but its command was unable to prevent the participation of some officers and sergeants in the conflict. The federal government helped negotiate the Pact of Pedras Altas, putting an end to the conflict and prohibiting re-election in future elections.[6][7]

The tenentist-liberating alliance

In January 1924, the opposition from Rio Grande do Sul united in the Liberating Alliance to contest the parliamentary elections for federal deputy and senator. This ticket was a heterogeneous alliance of three groups, the members of the Federalist Party, the "democrats" and PRR dissidents. Their common cause was to revise the Constitution of Rio Grande do Sul and break the power monopoly of Borges de Medeiros, who they considered to be authoritarian.[8] In the same period, conspiracies in the barracks intensified.[9] The tenentists planned to raise a great "revolutionary arc", from Rio Grande do Sul to São Paulo. The participation of civilians from Rio Grande do Sul would be advantageous, but it was not certain; the Pact of Pedras Altas could keep them away from a new conflict.[10]

However, many liberators were disappointed with the pact's terms, as it did not result in Borges' immediate departure from power.[8] Discontent was even greater due to non-compliance with part of what was agreed by the state and federal governments. The liberators still suffered persecution, and several of their leaders were sent into exile. In this way, the state political crisis was not over.[11][1] For the disaffected, siding with the army conspirators may have been seen as a continuation of the 1923 struggle.[12] Since before the 1924 revolt in São Paulo, lieutenants and liberators had already maintained contact.[13]

The resulting alliance was circumstantial. Both wanted to overthrow rulers — the lieutenants, Artur Bernardes, and the liberators, Borges de Medeiros. The lieutenants demanded the moralization of politics, the secret ballot and other issues of national scope, while the liberators were interested in agribusiness production, smuggling on Brazil's border and other local issues.[14] This did not prevent Assis Brasil from exerting an ideological influence on lieutenant officers.[15] Tenentist Juarez Távora highlighted the "alignment of goals regarding national aspirations between the rebels in São Paulo and the opposition from Rio Grande do Sul".[16] Government supporters, on the other hand, presented the rebels as opportunists, "rioters who did not accept the political defeats they suffered".[17]

The south in the plans for São Paulo

Rio Grande do Sul was of great interest as it had the largest concentration of army forces,[18] a reflection of its position on the border with Argentina. The terrain was especially favorable to cavalry; there were three divisions of this branch and one of infantry.[19] It would be up to a revolt in the south of the country to distract the army force based in Porto Alegre, preventing it from reinforcing the loyalists in São Paulo.[20]

Emissaries from the center of the country, usually officers with false identities, came to weave the conspiracy. The most notable was captain Juarez Távora.[10] The distance between the units was an obstacle. Messages could only be delivered in person, as the Post Office was monitored by loyalists. Santo Ângelo was 100 kilometers from São Luiz Gonzaga which, in turn, was 120 kilometers from São Borja. The messengers did not always arrive on time. Even abroad, the government monitored the conspiracy, bribing telegraph officials.[21]

Repercussions of the São Paulo Revolt of 1924

The new tenentist uprising, which began in July 1924, had a smaller scope than expected, and at first was limited to the city São Paulo.[10] The committed officers in Rio Grande do Sul awaited the order for a revolt, but were caught off guard by the events in São Paulo. There was no time to warn them, and the conspirators' focus was São Paulo.[22] The conflict gave Borges de Medeiros the opportunity to reconcile with Artur Bernardes, contributing with battalions of the Military Brigade to the loyalist military effort.[23][24] This institution was a true state army, battle hardened in the previous wars in Rio Grande do Sul's territory and guarantor of the PRR's power.[25]

Within Rio Grande do Sul, the government reacted by persecuting the opposition press and former revolutionaries of 1923. In public, Liberating Alliance politicians declared their support for Artur Bernardes. Within the group, however, whether or not to align with the government was controversial.[26] The liberators would have something to gain by approaching Artur Bernardes, but he was already reconciling with Borges de Medeiros, and thus, discontent with the state government became louder.[12]

The alliance with the tenentists, until then considered unfeasible, was sealed in the following months; during the negotiations, the Alliance deputy João Batista Luzardo stood out. Assis Brasil, as leader of the liberators, accepted the position of "civilian leader of the revolution", even without participating in its planning. General Isidoro valued this membership, as Assis' political prestige would attract more support for the revolt. On the front line, the opposition forces would be represented by warlords such as Honório Lemes, Zeca Neto and Leonel Rocha.[27][28] Rumors about this alliance soon circulated.[13] The start date, scheduled for 7 September, was postponed due to government surveillance.[5]

Coordination with Paraná

The uprising in São Paulo was unable to defend the state capital and withdrew to the interior, where the rebels reestablished themselves in western Paraná. On 5 October, civil and military liaison officers in Rio Grande do Sul met with generals João Francisco and Olinto Mesquita de Vasconcelos in Foz do Iguaçu. The emissaries argued for the viability of a new revolt in Rio Grande do Sul, and Juarez Távora, a member of the São Paulo column, was appointed to coordinate it. Antônio de Siqueira Campos, a veteran of the 1922 uprising exiled in Argentina, joined the preparations.[29] Initiating a revolt in Rio Grande do Sul was necessary to distract the loyalists in Paraná.[30] However, the decision was taken in the absence of the supreme commander, general Isidoro, who had not yet arrived in Foz do Iguaçu.[31]

According to João Alberto Lins de Barros:[32]

...each garrison, fearing the first step, waited for the other to decide to act. The young officers were ready to fight. However, the top brass appeared to be uneasy about the development of events in São Paulo [...] The situation of the revolutionaries, finally located in the Iguaçu region, worsened day by day. It was necessary to hasten the uprising in Rio Grande, at any cost.

The federal government did not trust the army in Rio Grande do Sul, and left the units' arsenals empty.[30] In Buenos Aires, Assis Brasil had been purchasing weapons since the beginning of October, smuggling them, inside fruit boxes, across the Argentine border in Paso de los Libres.[33] The date was set for 29 October.[34] On the 23rd, the press reported Honório Lemes' participation in an imminent military revolt. Members of the Liberating Alliance denied the rumors.[35]

Overview

First uprisings

Today, 29 October, by order of general Isidoro Dias Lopes, all army troops from the garrisons of Santo Ângelo, São Luiz, São Borja, Itaqui, Uruguaiana, Sant'Ana, Alegrete, Dom Pedrito, Jaguarão and Bagé rise up, today united by the same cause and the same ideals, the revolutionary forces from Rio Grande do Sul rise up from Palmeira, Nova Wutemberg, ljuí, São Nicolau, São Luís, São Borja, Santiago and from across the border to Pelotas and, today, the revolutionary leaders Honório Lemos and Zeca Neto enter our state, all in accordance with the great plan already organized.

— Captain Luís Carlos Prestes' manifesto, leader of the revolt in Santo Ângelo[36]

This panorama was very exaggerated. Only four army units had joined: the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Independent Cavalry Regiments (RCI's), respectively based in São Borja, São Luiz Gonzaga and Uruguaiana, the 1st Railway Battalion (BF), from Santo Ângelo, plus a section of the 3rd Horse Artillery Group, from Alegrete. Among civilians, Honório Lemos and Zeca Neto kept their promises.[37]

_24.jpg.webp)

In Santo Ângelo, the revolt began on the night of 28 October. Captain Luís Carlos Prestes and lieutenant Mário Portela Fagundes arrested the commander of the 1st Railway Battalion in his home and took over the unit based on a forged telegram from the commander of the Military Region that transferred command to Prestes. Thanks to his prestige among soldiers, support was almost total. Among the officers, only the medical captain and lieutenants José Machado Lopes and Hugo Carvalho did not want to join. The rebels surrounded the residence of the intendant of Santo Ângelo and presented a letter requesting his weapons and ammunition, thus obtaining around 50 rifles.[38] Many civilians joined the uprising, as the Missões region was a stronghold of oppositionists and PRR dissidents.[39]

The three cavalry regiments were in revolt in the early hours of 29 October. In São Luiz Gonzaga, the revolt was led by lieutenant João Pedro Gay, from the 3rd RCI.[40] At around 2:00 at night, patrols occupied the city and surrounded the Hotel Central, where the commander was. The quartermaster's office and the telegraph post were occupied, establishing contact with the other revolts. The city was a PRR stronghold, under the influence of Pinheiro Machado, but according to João Alberto Lins de Barros, there was no local resistance. This can be attributed to the local Liberating Alliance, which received weapons and leadership positions, and to the reinforcements that later came from Santo Ângelo.[41]

In Uruguaiana, Juarez Távora crossed the Argentine border the night before, meeting with opposition colonel Áfrico Serpa and other military personnel, including the inspector of the 5th RCI, Ambire Cavalcanti. Honório Lemes arrived the next day to take command of the uprising. The revolt was facilitated by the city being a stronghold of Batista Luzardo,[42] receiving, from the beginning, the support of figures from the local elite.[43]

A PRR dissident, Dinarte Rey Dornelles, actively participated in São Borja,[44] welcoming Siqueira Campos when he arrived clandestinely from Argentina. With the collaboration of captain Ruy Zubaran and lieutenant Aníbal Benévolo, Siqueira entered the 2nd RCI barracks at 20:00 on the 28th, finding the soldiers in formation in the courtyard. When Aníbal Benévolo introduced the newcomer, ecstasy was widespread. At 2:00 troops were already heading to occupy the city center.[30][45]

From Santana do Livramento, headquarters of the 7th RCI, numerous officers asked the rebels for help, as they had boarding orders, but wanted to join the revolt. In response, agents cut the telegraph line to Rosário do Sul on 1 November and transmitted to Livramento the news of the destruction of several sections of the railway, halting shipment. This rebel group went to Caverá, where much of the weapons had been hidden since 1923. Several groups of liberators, gathered on 6 November, were armed in the region, fighting some battles against the loyalists.[46][47][48]

Administration of the occupied territory

The rebels appointed two "governors", one military officer and one civilian, in Uruguaiana, São Borja and São Luiz Gonzaga.[49] The manifesto published in Uruguaiana clarified the functions of the military governor (Juarez Távora): the "organization of the city's policing and security service, the call up of reservists, organization of units and contingents, superintendence of the requisitions service, organization of martial courts and all measures of a military nature". The superintendent, vice-intendant, municipal councillors, police chief, district sub-intendents, police sub-delegates and the administrators of the public market and the slaughterhouse were removed from their positions.[50]

In both Santo Ângelo and Uruguaiana, revolutionary manifestos promised to respect property, maintain public order and not disturb the population. In Uruguaiana, it specified that "policing in the city will be carried out by armed volunteers under the supervision of a police officer in order to guarantee everyone absolute peace of mind. Civilian courts will be able to continue to freely exercise its functions in the trial of common crimes".[36][50] The police authorities, on the other hand, presented the rebels as agitators and subversives, perpetrators of looting, depredations and murders against the population.[51]

The most controversial measures were the requisitions of goods and money for the war effort. In Uruguaiana, weapons stores had to hand over their stocks to the military government. Foodstuffs in warehouses, automobiles, and pack and saddle animals were listed and presented to the government by their owners. Merchants and individuals were "strictly obliged" to provide the goods required by the military government, which would be responsible for their subsequent restitution or compensation. Requisitions without authorization from the military governor were illegal.[52]

The population did not always understand or accept the requests, and sometimes responded by hiding goods or resisting. The revolutionary command did not want to deliberately harm the population and tried to impose a regularized process, with limits, but considering the size of the troops, not all of them with firm discipline, excesses and violence occurred. The Police Headquarters considered the bureaucratic process as a "formal excuse" for "free looting". The witnesses in the police investigation were always declared supporters of legality. Still, even this inquiry recognized the revolutionary command's punishments for cases of insubordination and abuses.[53]

The revolutionary army

Assis Brasil, as a civilian leader, remained in refuge in Uruguay,[37] where the "Revolutionary Committee" was installed in the city of Rivera.[43] In Rio Grande do Sul territory, the movement was led by alliance leaders and army officers.[37] The culture shock was stark. Young officers, trained in military science at the Military School of Realengo, served alongside veteran warlords, some even illiterate, but well-versed in the local terrain and people.[30][54] The warlords had their own style of fighting, and ignored the standards of technical warfare (such as a better security service and organized General Staff) demanded by army officers.[55]

The warlords referred to themselves with officer ranks, and each group of irregulars was independent and only obeyed its leader, only recognizing the hierarchical superiority of Honório Lemes, the only one with the title of general. This created command difficulties. Prestes reported that it was necessary to talk for hours with each warlord, over chimarrão and churrasco, until convincing them of a measure through suggestion.[55][56][57]

Honório Lemes ridiculed Juarez Távora for being a bad horse rider.[58] War on horseback, still important in a time of incipient motorization, was well understood by the Rio Grande do Sul irregulars.[54] Both sides appropriated all the horses they found on the way, increasing their mobility and denying the enemy mounts.[59] The clothing was typically gaucho in style, distinguished by the red scarves and ribbons, symbols of the revolution.[60] Many carried obsolete weapons: garruchas, shotguns and Comblain and Chassepot rifles. The Winchester rifle, more recent and widespread in rural areas, had less range and power.[61] This diversity of weapons made remuniciation very difficult.[62]

The columns remained in constant movement, cutting railway and telegraph connections. Battles were marked by cavalry charges, often ending in hand-to-hand combat, with spears and other melee weapons.[63] As typical of gaucho wars, the 1924 revolt was bloody,[64] with victories culminating in the beheadings of wounded men and prisoners. These executions were typically personal reckonings, carried out out of sight of commanders. Juarez Távora protested to Honório Lemes, who banned the practice.[65] Another characteristic of the Rio Grande do Sul struggles, seen in 1924, was the temporary asylum abroad. The defeated men had their weapons taken from them, but lived in freedom and returned as soon as possible.[66][67]

The course of the campaign was bad for the civilian leaders.[68] Even so, Juarez Távora and João Alberto Lins de Barros praised the tactical sense of Honório Lemes, "the greatest expert on the roads, shortcuts, river crossings and wetlands in that entire region".[69][70] Officials with formal training, and not just the warlords, were involved in several defeats.[71]

Loyalist reaction

The largest military hub in Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Maria, was not threatened by the revolt.[19] The loyalist reaction was immediate, led by Borges de Medeiros and general Eurico de Andrade Neves, commander of the 3rd Military Region.[72] The American consul in Montevideo estimated the number of army personnel available to suppress the revolt at 15,000 men or more, but for him, federal troops were not used in the most serious combats, as they had sympathy for the enemy.[73] João Alberto Lins de Barros also stated that the loyalist army lacked will.[69] The American consulate reported to the State Department the call of 1,900 men from the Public Forces of São Paulo, Minas Gerais and Bahia to Porto Alegre.[73][lower-alpha 1]

The Military Brigade was placed at the disposal of general Andrade Neves.[74] Better equipped than the federal army at the time of the revolt,[75] it was concentrated in Porto Alegre and in the Rio Grande do Sul's pampas,[25] a stronghold of the Liberating Alliance.[76] In addition to the regular troops and seven active Auxiliary Corps (ACs), 29 corps were mobilized.[72] These small irregular units, known as "provisionals" (provisórios), were recruited from civilians and were consisted essentially of cavalry.[18][1][77]

The federal government extended the state of emergency to Rio Grande do Sul[78] and ordered the censorship of news about the revolt. The newspaper Correio do Povo, in protest against the appointment of a censor officer to its editorial staff, did not publish any news about the revolt from 6 to 27 November. Still, the newspaper referred to the uprising as "seditious" and "subversive", the same terms used in official government notes.[79] O Paiz, a newspaper in Rio de Janeiro, only started reporting on the revolt on 12 November, always with a favorable stance to the government.[78]

Rebel regions

By the end of 29 October, the rebels controlled the banks of the Uruguay River, with the exception of Itaqui.[80] After a series of defeats, in mid-November the last organized stronghold was São Luiz Gonzaga.[81] From there, the most important fighting took place in the northwest of the state.[19] Meanwhile, the revolt continued in the south in the form of a guerrilla, and from mid-November until December it locked some loyalist troops.[82] For historian Glauco Carneiro, in this period "civil leaders were engaged in an inconsequential fight".[64] By early 1925, the revolt was close to an end, but it was not over.[83]

Operations in the south

Alegrete

Alegrete's loyalists intended, on 29 October, to destroy the Capivari bridge, cutting off railway communications with Uruguaiana. The contingent sent to the task included provisional members of the Military Brigade, loyal to the government, and a section of the 2nd Horse Artillery Group, under João Alberto Lins de Barros, committed to the uprising. When the train encountered a group of rebels, João Alberto managed to disarm the provisionals and arrest their leader, lieutenant Larré. His support was complete, but the intended attack on Alegrete could only take place in the early hours of 30 October, as he had to wait for the arrival of Juarez Távora with reinforcements from Uruguaiana.[84][85][76]

Alegrete would resist, as it was a PRR stronghold, under the influence of Osvaldo Aranha,[76] and the base of the 2nd Cavalry Division, whose commander, General Firmino Borba, mobilized the remainder of the 2nd Horse Artillery Group and the 2nd Auxiliary Corps.[86] Historian Glauco Carneiro cited a small number of attackers: 180, leaving 50 behind on the train, but reinforced by 20 from lieutenant João Alberto.[64] Hélio Silva quantified 300 attackers and 500 defenders of the army, not counting the provisional members of the Military Brigade.[87] The reinforcements requested by the general had not yet arrived; for military historian Virgílio Muxfeldt, the rebels' problem was not the enemy strength, but possibly their own inexperience and vacillation.[88] Glauco Carneiro, on the other hand, emphasized the time the defenders had to prepare.[64]

The rebels attacked in two wings, reaching the Alegrete's main street. Lieutenant João Alberto provided accurate artillery support with a cannon. After four hours of fighting, when ammunition ran out, loyalist resistance remained firm, and the command of the attackers ordered the left wing to retreat. Due to a misinterpretation of orders, the right wing thought there was a general retreat, and the attackers fled in disarray. João Alberto, covering the retreat, had to abandon his artillery piece when he was bypassed on the flanks by the loyalist cavalry, who slit the throats of the wounded left behind. With heavy casualties, the rebels crossed the Ibirocaí River and concentrated again in Uruguaiana.[64][89]

Juarez Távora ordered another attack on 3 November, and was again defeated.[90] The disaster was used by civilians to discredit the army soldiers warfare style. Soon after the defeat, Honório de Lemes arrived in Uruguaiana,[55] taking command of the column. Juarez Távora remained his chief of staff.[30] Together, they had around 800 liberators and 200 soldiers from the 5th RCI.[86] Domingos Meirelles quantified 3 thousand combatants, of which only 200 were professional soldiers; Of the irregulars, only a thousand had modern weapons. Along with them came 5 thousand horses.[61]

Guaçu-Boi

In Alegrete, General Borba was reinforced by a detachment from the army (elements of the 9th and 13th RCIs and an artillery battery) and another from the Military Brigade (1st Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Auxiliary Corps and Patriot Corps, constituting a state cavalry brigade), with which he advanced against Uruguaiana. The state brigade, under colonel Claudino Nunes Pereira, followed the railway. To its left, the army detachment, under colonel Estevão Taurino de Rezende, accompanied it along the highway.[82][91] The rebels abandoned Uruguaiana on 5 November and headed towards Santana do Livramento,[62] where they expected the 7th RCI to join. This unit, although small in strength, had a large stock of weapons and ammunition.[61][76]

Honório Lemes' column would first pass through Quaraí, moving at night, along unknown roads and shortcuts, to surprise the enemy.[92] According to João Alberto, however, there was no military professionalism in this movement: "instead of a covered march, avoiding demonstrations that could reveal us to the enemy, the general acted carelessly, without thinking about the opposing forces that were supposed to be distant". Several sources agree, attributing the failed security to the civilian component of the column.[92][93] Muxfeldt, however, noted that the soldiers of the 5th RCI were the ones responsible for the security of the column. According to Juarez Távora, the order did not reach the regiment commander, and other sources claim that he deserted.[62]

The vanguard of the state brigade was led by deputy Flores da Cunha, a veteran of 1923. The direction of the rebel column was noticed on 7 November.[94] Loyalists also moved around carefree. But by chance, they marched faster, woke up earlier, and detected their enemy in advance.[92] At midnight on the 8th, Flores da Cunha informed colonel Claudino of the enemy's approach,[94] who left near Guaçu-Boi in the early hours of the 9th. The soldiers stopped to rest, and Honório Lemes informed Juarez Távora: "until now there was danger, but from now on we are safe". The loyalists, camped two to three kilometers away, attacked by surprise at 07:00.[72][92] The loyalist victory was decisive, and would determine the course of the conflict:[93]

The revolutionaries, harassed on all sides, were panicking. The ground was covered with the most diverse objects that fell from the overturned carts. Musical instruments, bass drums, accordions, horns, were mixed with spears, tents and pans. The stampede became widespread. Honório galloped, indifferent to the bullets, shouting to his men: — "Extend line, extend line". An army platoon, commanded by lieutenant Manuel Aranha, sustained the fight, to allow the troops to regroup and begin the retreat to a more advantageous position.[66]

The bulk of the rebels withdrew with Honório and Juarez towards Quaraí. João Alberto, Cordeiro de Farias and others remained in isolated groups, returning via Ibirocaí to Uruguaiana, which the loyalists were already occupying. Many rebels took temporary refuge in Argentina.[66] Honório Lemes' column had perhaps only a fifth of its initial strength remaining.[62]

Barro Vermelho

On the same day as the battle of Guaçu-Boi, captain Fernando Távora revolted the 3rd Engineering Battalion (BE), in Cachoeira. The unit's commander was arrested and 118 men left the barracks towards Passo de São Lourenço, on the Jacuí River.[44] The Military Brigade estimated the number of rebels at 200, including civilian supporters.[95] Small and isolated in the center of the state, the only option for this force was to join the liberators of Honório Lemes and Zeca Neto.[62] They were pursued by part of the 3rd BE itself, part of the 11th AC and the 2nd Company of the 1st Infantry Battalion of the Military Brigade, coming from Santa Maria. On 10 November, the rebels were defeated at the Barro Vermelho farm.[95][96] The remnants of that fight were unable to connect with Zeca Neto and dispersed towards Uruguay, via Aceguá.[81][96]

Saicã

In Quaraí and Serra do Caverá, Honório Lemes' column was reinvigorated by hundreds of men mobilized by his comrades from 1923. From there, he continued to the weakly defended municipality of Rosário, where he would confiscate the army cavalry at the National Stud Farm of Saicã and the Horse Supply Post from São Simão.[65][97][98]

The Stud Farm, defended by 90 men from the 12th RCI, was attacked on 13 November. The detachment commander received an ultimatum to surrender, signed by Juarez Távora: "general Honório Lemes da Silva, at the head of 1,200 men, has just completely besieged the forces under your command". 100 men from the 15th AC, from Rosário, came to his rescue, but were defeated in a trap. 80 men defending the bridge over the Santa Maria River were captured. On the 14th, the defenders of Saicã surrendered all their resources. Honório Lemes continued to Cacequi on the 16th, cutting telegraphic communications and invading the Supply Post, which had only 60 defenders.[65][82][99]

The attack on Saicã prompted a note of protest from the Minister of War, marshal Setembrino de Carvalho, accusing Honório Lemes of breaking the Pact of Pedras Altas.[65]

Cerro da Conceição

The column headed towards São Gabriel and stopped at the wetlants in Inhatium on 17 November.[82] The loyalist persecution column was in the same municipality,[lower-alpha 2] commanded by lieutenant colonel Augusto Januário Corrêa and consisting of the 15th AC and the 2nd Cavalry Regiment of the Military Brigade, coming from Santana do Livramento. To set up an ambush, Honório Lemes went back to Cerro do Caverá, a very familiar terrain, full of hills covered in forest and brooks.[65][100]

The loyalist column moved with a squadron from the 15th AC in the vanguard. Its careless movement culminated in an ambush on 23 November, in the town of Cerro da Conceição. The rebels waited for the vanguard to pass and attacked the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. Despite his advantage of surprise, Honório Lemes was counterattacked and abandoned his positions.[100] This combat was perhaps the most violent of the conflict, leaving dozens of people dead and injured. Honório lost old companions, and lieutenant colonel Corrêa had his leg amputated. Honório's column consumed a large part of its ammunition, making an attack on Livramento impossible. Juarez Távora, disenchanted with the outcome of the revolt, went to Uruguay, from where he would later return to Foz do Iguaçu.[101][102]

The loyalist effort was reorganized on the 23rd. The new detachment, consisting of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment and 1st and 15th ACs, would be commanded by lieutenant colonel Emílio Lúcio Esteves. Initially he was busy repairing the railway line between Livramento and Rosário.[103][104]

Camaquã River

After Cerro da Conceição, Honório Lemes passed through Rosário, where he sent a detachment to take goods and money on 26 June. The police investigation into the revolt also mentioned other "raids" in São Gabriel and São Vicente.[97] His next objective was in Caçapava and Lavras, where he hoped to join the 3rd BE rebels, without knowing that they were defeated. His next attempt at connection was with Zeca Neto, who had crossed the border in Dom Pedrito, on an undefined date, with around 40 men and then took refuge along the Camaquã river, which he knew well.[105]

In the pursuit of Honório Lemes, lieutenant colonel Júlio Rafael de Aragão Bozzano, commander of the 11th AC, a lawyer, journalist, and intendant of Santa Maria stood out.[68] On 5 December, Honório finally joined forces with Zeca Neto on the banks of the Camaquã river, south of Caçapava, but was defeated in the region of Passo do Velhaco.[lower-alpha 3] The pursuit continued until the fighting at Passo das Carretas, on the 8th, and Passo do Camaquã, leaving the rebels no longer able to fight.[97][105] The rebels passed through Candiota, on their way to Uruguay, on the 10th, and finally crossed the border between Passo da Mina and the Aceguá hills,[106] on 13 December.[105] This border region was defended by the 10th AC. According to an official note from the 3rd Military Region, the rebels hid their weapons in the woods and caves and entered Uruguay unarmed.[106]

Galpões

Parallel to the conflict in Rio Grande do Sul, tenentists in the Brazilian Navy launched a revolt in the battleship São Paulo on 4 November. Without support from the rest of the navy, the ship headed south, hoping to join its fellow gaucho rebels.[107] Unaware of the real situation in Rio Grande do Sul, on the 9th the ship intended to dock at the Port of Rio Grande, but the local authorities ignored all their messages. São Paulo's officers then decided to deliver the ship in Uruguay.[108] To continue the fight, they tried to board an Argentine ship to Foz do Iguaçu, but at the request of the Brazilian authorities, they did not receive authorization.[109]

Lieutenant Ademar Siqueira and some sailors went to Rivera, where they would wait for their companions in Montevideo. Without authorization from the lieutenants, they accepted the call from colonel Julio Barrios,[lower-alpha 4] who was organizing a new invasion of Rio Grande do Sul in Uruguay. The formed column had 200 liberators and 25 sailors.[105][110]

The Uruguayan and Brazilian authorities noticed the formation of the column. A rebel picket was repelled at the border, near Santana do Livramento, on 26 November. Colonel Barrios again attacked this city on 10 December, and the following day, he was defeated by the Esteves detachment in the Galpões region. Short and violent, the battle ended with a chase into Uruguayan territory. The escape was much worse for the sailors, who were not used to riding. Sinhô Cunha's provisionals beheaded twelve prisoners, including eight sailors, creating an international incident and forcing Brazil to send its formal apology to Uruguay. Aldo Ribeiro, a historian of the Military Brigade, mentioned that some of the rebels' lines of fire, during the battle, were within Uruguayan territory.[105][111][112][113]

The Uruguayan border remained under surveillance. A new revolutionary column, with around 300 men, entered the Quaraí river region, defeating a surveillance picket from the 2nd AC on 3 January. On the 5th, these rebels were defeated at the Sarandi pass and then at the Potreiro pass, returning to Uruguay.[114]

Operations in the west

Ijuí

On 29 October, Luís Carlos Prestes, from Santo Ângelo, had Ijuí as his first target, where the railway connecting his city to the rest of the state passed. In the morning, around 40 rebels were repelled by military and civilians when they tried to attack the city, losing their commander, sergeant Teodósio Boelner, in combat. Due to this setback, the rebels only stayed in Santo Ângelo for three days. Prestes requisitioned the city's automobiles and withdrew all his troops to São Luiz Gonzaga, a city with no railway connection, and therefore easier to defend.[115]

The government sent reinforcements such as the 7th Battalion of Caçadores (BC), from Porto Alegre, to the Missões region.[115] Santo Ângelo was reoccupied by loyalists from Ijuí and Santa Rosa.[96]

Itaqui

The 1st Horse Artillery Group (GACav), based in Itaqui, did not join the revolt, separating the rebels in São Luiz and São Borja from their companions in Uruguaiana. Consequently, the city was targeted from two directions,[116][117] since 4 November.[lower-alpha 5] Loyalist resistance was organized by Osvaldo Aranha, a local PRR politician, and captain Carneiro Pinto,[80][116] counting on a provisional body of the Military Brigade, made up of veterans from the previous year, and the 1st GACav.[117][116] The attack was commanded by Siqueira Campos and Aníbal Benévolo.[118]

Both sides called in reinforcements.[118] The rebel reinforcements coming from the south were unable to help;[lower-alpha 6] in Uruguaiana they received no communication from their comrades, they feared a loyalist attack from Alegrete and were distracted by the call of some officers from the 7th RCI, from Livramento.[88] To the north, Siqueira Campos received the 1st Company of the 1st BF, and Osvaldo Aranha, a civilian contingent from Santiago and the 7th Auxiliary Corps of the Military Brigade.[119][120]

To block the loyalist reinforcements, Aníbal Benévolo went with 70 men to the Recreio railway station and the Padre ranch, where he was defeated and killed in combat on 12 November. Reinforcements continued to Itaqui, from where the loyalists began a counteroffensive,[119][120] achieving a clear advantage on the 13th.[118] Threatened with being surroundered, Siqueira Campos headed towards Uruguaiana, finding the passages over the Ibicuí River blocked.[96] With 200 men, he escaped to Argentina, while the 1st BF company managed to retreat to São Borja.[118]

The siege of São Luiz Gonzaga

The units that had attacked Itaqui and new supporters rushed to São Luiz Gonzaga.[121] These forces, called "1st Brigade of the Center Division",[105] was commanded by Luís Carlos Prestes, commissioned with the rank of colonel in a letter from Isidoro Dias Lopes. This message was delivered by colonel João Francisco, coming from Argentina, when Prestes was still in São Borja.[122][lower-alpha 7] The title was important to reinforce his authority with the liberators.[123]

There, 1,500 soldiers and civilians resisted, with just 700 rifles.[121] The others only had a revolver and ammunition on their belts. The troops were heterogeneous, poorly structured and lived without pay. The best armed unit was the 3rd RCI, with a rifle for each man, but Prestes trusted his 1st BF more, whose training he had handled personally, and whose soldiers trusted him. Isidoro had promised a shipment of weapons through Argentina, but a new emissary from Paraná warned that they would not arrive due to diplomatic pressure from the Brazilian government.[124]

The defenders of São Luiz were distributed within a radius of 90 kilometers around the city,[125] in positions on the bridge over the Piratini River, in the direction of Santiago, and on both banks of that river; in the passages of the Ijuí River and Passo do Guerreiro, in the direction of Ijuí; and at the crossings of the Ijuizinho river and Estrada do Cadeado, in the direction of Cruz Alta.[96] Victorious in the south, the loyalists transferred some units from there to the Missões region.[126] The government was preparing a siege of seven columns around São Luiz,[127] in the directions of Santiago, São Borja, São Nicolau, Serro Azul, Santo Ângelo, Cruz Alta and Tupanciretã. This "iron ring" had up to 14 thousand men;[128][129] in Prestes' estimate, there were more than 10 thousand.[130]

At the end of November, the rebels were informed of the loyalist concentration in Tupanciretã, southeast of São Luiz, with a strategic position on the railway. Interested in seizing weapons and ammunition, Prestes led an attack on that city on 2 December. With 800 men, the attackers were outnumbered and outgunned by the loyalists, who had two army battalions, two auxiliary corps and could easily call in reinforcements. The seven hours of fighting ended with a retreat back to São Luiz.[lower-alpha 8]

Escaping the "iron ring"

The government wanted to win a decisive fight and expel the survivors to Argentina.[131] On 30 December, the Buenos Aires newspaper La Nación speculated about the three remaining alternatives for the revolutionaries: "cross the Uruguay River [...], try to open the way to the north, [...], or else fight for the honor of arms, without plausible hope of victory [...]. In any of the three cases, this would inevitably mean the death of the revolution in the territory of Rio Grande do Sul".[132] Since the previous month, Isidoro had already recommended the second option, calling on the rebels from Rio Grande do Sul to join him in Paraná.[133]

The loyalists intended to tighten the siege on 30 December.[131] The 1st Cavalry Regiment of the Military Brigade, the vanguard of the Tupanciretã detachment, had already been moving towards São Luiz since the 24th, fighting some skirmishes along the way.[134] Prestes abandoned the city on the 27th and made his way north. Taking advantage of the lack of flank guards in loyalist detachments, he divided his force into smaller groups to sneak between enemy columns.[127][135] It was necessary to avoid unnecessary expenditure of ammunition.[129] Still, his column had to face strong contingents of provisionals on the way.[64] It was divided into three mixed detachments of military and civilians: the 1st, commanded by lieutenant Portela Fagundes, was organized around the 1st BF. The 2nd, by lieutenant João Alberto, around the 2nd RCI, and the 3rd, by lieutenant Siqueira Campos, around the 3rd RCI.[136]

When the loyalists occupied São Luiz Gonzaga, the city was empty.[137] Passing through São Miguel,[127] on 29 December the rebels crossed the Ijuizinho river,[138] and the following day they encountered the 3rd squadron of the 11th AC in Passo da Cruz, near Ijuí. The rebels forced passage over the Conceição stream.[129][139] The Military Brigade sent colonel Claudino Nunes Pereira with reinforcements,[lower-alpha 9] but on 1 January, Siqueira Campos' detachment forced a gap through which the entire column crossed the Ijuí River. João Alberto's detachment served as rearguard.[136] The death in an ambush of lieutenant colonel Bozzano, commander of the 11th AC, undermined the official discourse that the revolt was almost pacified.[140]

From Ijuí, the column continued towards Palmeira.[138] In the same direction, lieutenant colonel Esteves had just taken over another loyalist detachment,[lower-alpha 10] with 1,600 men. On 3 January, the opponents clashed in Ramada, in one of the bloodiest battles of the conflict.[141] The battle lasted from 8:00 in the morning until the late afternoon hours. The loyalists employed artillery, but its effect was more psychological than material. Their aim was to block the rebels or redirect them south.[142] Prestes' column managed to get through, but paid a heavy cost:[129] approximately 50 dead and 100 wounded.[141]

The border with Santa Catarina

From Ramada, Prestes changed direction and took his column towards Campo Novo, where he defeated a group of loyalists on 5 January. From there, his column entered the trail on the way to the Military Colony of Alto Uruguai, heading towards the Santa Catarina border.[138] The column escaped the siege, consolidating Prestes' image among the revolutionaries.[143] The best route from Rio Grande do Sul to Paraná was via Passo Bormann, Chapecó and Xanxerê, but a patriotic battalion blocked this passage. The rebels followed another route to Porto Feliz, in the extreme west of Santa Catarina,[144] crossing tributaries of the Uruguay River (Turvo, Guarita and Pardo).[138][145]

Both sides faced poor conditions and a hostile environment.[146] The region was sparsely populated, and heavy rain made the inhospitable trails muddy. There were no camp tents and food was consumed sparingly. The forest offered no pasture for horses. Accustomed to life on horseback, Rio Grande do Sul civilians were discouraged by the prospect of fighting on foot, making their way through the forests with machetes. Nor were they interested in fighting far from their homeland, as their political objective was at the state level. Consequently, the Rio Grande do Sul chiefs emigrated with hundreds of men, taking their weapons and animals with them and lowering the morale of the army officers.[144][147][148]

The loyalist persecution was led by colonel Atalibio Rezende's Group of Detachments. One of these detachments was that of colonel Pereira, whose vanguard, the 6th AC, reached the rebels on 24 or 27 January,[lower-alpha 11] during the crossing of the Pardo River. The loyalists recorded having inflicted heavy casualties in a surprise attack, including killing lieutenant Portela, whose detachment covered the rear. João Alberto Lins de Barros added that Portela, as was customary, waited until the last of his men had passed. His death was "one of the losses he [Prestes] felt most".[149][150] His companions who had already crossed the river could do little.[151]

The march to Santa Catarina lasted until 28 January.[145] On 1–2 February, the last elements of the rearguard left Porto Feliz, in Santa Catarina territory.[152] The Military Brigade maintained a presence on the left bank of the Uruguay River, watching for a possible return of the rebels.[153]

Link with the Paraná Campaign

Operations in Contestado

Until its junction with the remnants of the São Paulo Revolt, Prestes' column spent 45 days in the Contestado region, in western Paraná and Santa Catarina, where it operated as a guerrilla group.[154] Desertion was still a problem, notably that of the 3rd Detachment commander, lieutenant Gay.[129][155] On the other hand, a regional colonel, Fidêncio de Melo, joined the rebels, occupying the border town of Dionísio Cerqueira on 2 February. On the 7th, Prestes reached Barracão, in Paraná, a city neighboring Dionísio Cerqueira. The revolutionary territory in Paraná, under attack by general Cândido Rondon, was further north, beyond the Iguaçu River. Prestes would remain at this point for more than a month. He contacted Isidoro, reporting he had 800 men, of whom less than 50 were armed, and requesting weapons and ammunition. This request could not be granted, as Isidoro's logistical situation was also precarious.[156] In Rio de Janeiro, O Paiz repeatedly trumpeted the rebels' defeat, but the loyalists never achieved a decisive victory.[157]

Prestes wanted to relieve loyalist pressure in Paraná, while Rondon realized that his rear in Santa Catarina was poorly guarded. Consequently, the loyalist command created the Palmas Detachment and disembarked four Auxiliary Corps in Porto União that followed the São Paulo-Rio Grande Railway towards Paraná. These units, commanded by colonel Firmino Paim Filho, defeated a rebel offensive against Clevelândia, on 19 February. Colonel Claudino Nunes Pereira brought reinforcements from Rio Grande do Sul the following month. These two loyalist columns had a friendly fire incident in the village of Maria Preta, on the way to Barracão, on 24 March. At this time Prestes was already leaving Barracão, finally joining the São Paulo on 3 April, in the town of Benjamin, between Catanduvas and Foz do Iguaçu.[158]

Formation of the Revolutionary Division

The junction of the Rio Grande do Sul rebels with the São Paulo ones occurred too late to avoid the latter's defeat in Catanduvas. The remnants retreated to the Paraná River. The revolutionaries who still wanted to fight organized themselves into a single formation, the 1st Revolutionary Division. Commanded by Miguel Costa from São Paulo, it was divided into two columns, one from São Paulo, under Juarez Távora, and the other from Rio Grande do Sul, under Prestes. This division spread throughout the interior of the country, continuing the tenentist struggle until 1927.[159][160][161]

This division is referred to in historiography as the "Miguel Costa-Prestes Column", or, more commonly, as the "Prestes Column"; a minority current uses "Miguel Costa Column". Formally, Miguel Costa was the commander. Prestes was nothing more than chief of the General Staff, but exercised informal leadership.[162][163] The name "Prestes Column" had existed since before April 1925, referring in isolation to the Rio Grande do Sul column on the part of its enemies.[164][146][165]

There is no consensus on the time frame for this column. Its beginning, depending on the source, is located at the beginning of the 1924 revolt in São Paulo, at the beginning in Santo Ângelo, at the reorganization in São Luiz Gonzaga or at the junction with the São Paulo rebels, in Paraná. From the beginning, there was no idea of marching to Paraná, much less the war of movement characteristic of the column. It was not born from prior planning, but acquired its own characteristics as a reaction to its inferiority in numbers and weapons.[166][163] Against conventional warfare, traditional in the army, Prestes defended a war of movement, which had already been used before in the interior of São Paulo and was also characteristic of the "gaucho style warfare". This procedure was put into practice after the escape from São Luiz Gonzaga.[167][168][169][170]

Legacy

_.jpg.webp)

The conflict left a large number of liberating civilian and soldiers from the army, navy and Public Force of São Paulo in exile in Argentina and Uruguay. Coordinated by general Isidoro, they remained in contact with each other and planned new revolts in the barracks and border incursions. The first was in September 1925, with a border invasion by Honório Lemes; the committed military elements did not rise up, and the civilian commander surrendered to Osvaldo Aranha and Flores da Cunha. A broader uprising began in late 1926, the "Lightning Column". The new uprisings were both civil and military, initiating in Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, and also including a border incursion into Santa Catarina. The rebels were again defeated. The issue of rebel exiles led the Brazilian government to sign an agreement with Uruguay, in force from 1927, for the latter to intern the officers responsible for the revolts in places far from the border.[171]

The alliance with tenentism gave prestige and national projection to the Rio Grande do Sul opposition, at the cost of new dissent within their ranks and the distancing of political leaders from their local bases. This was only remedied when the opposition reconciled with Getúlio Vargas, a PRR politician from São Borja, supporting his presidential candidacy in 1930.[172] Ironically, Vargas, whose family had been loyalists in previous years, joined forces with the tenentists to rise to power in the 1930 Revolution.[44][173]

In São Luiz Gonzaga, the revolt left a balance of social and economic losses. However, there was not the bloodshed expected by the community, which honored this fact with a grotto for Our Lady of Lourdes, inaugurated in 1926.[174] The conflict had little influence on the historical memory and cultural heritage of the Missões region until the 1980s, when it was rescued. Santo Ângelo was the city that most remembered the Prestes Column and used the story to promote tourism.[175] The old railway station building, deactivated in 1969, became the Prestes Column Memorial in 1996.[176] Further north, the period is commemorated in the name of the municipality of Tenente Portela and in a monument at the site of his death, in the current municipality of Pinheirinho do Vale.[151]

Notes

- Meirelles 2002, p. 305 mentions these contingents in combat. However, there is no mention of operations in Rio Grande do Sul by Minas Gerais troops, in Três Revoluções (Imprensa Oficial do Estado de Minas Gerais, 1976), by Paulo René de Andrade, which describes the operations of this institution against tenentists; the last days of 1924 were spent inside the barracks in Minas Gerais (p. 110). Os marcos históricos da milícia paulista (A Força Policial, 2000), by Waldyr Rodrigues de Moraes, also does not mention such operations.

- That is, "on the left bank of the Ibaré brook" on 18 November (Ribeiro 1953, p. 311).

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 332, gives other reference points in the region: the corner of Inferno, Passo dos Enforcados and Passo do Cação.

- Barrios was a former Uruguayan Army officer, according Ribeiro 1953 and Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022. Caggiani 1997 chama-o de Júlio Cesar de Barros.

- Donato 1987, p. 324, cites 1 November.

- The movement to the south did not occur, according to, Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, or was too late, according to Aragão 2021, p. 174.

- The document Promoção de Luiz Carlos Prestes ao posto de coronel is dated 14 November. It is cited in O tenentismo na Marinha: os primeiros anos (1922-1924) (São Paulo, Paz e Terra, 2005), by Francisco Cascardo Carlos Pereira, p. 757 and 813.

- Vitor 2021, p. 143, Savian 2020, p. 134 and Ribeiro 1953, pp. 335–336. The defenders were commanded by colonel Enéas Pompilio Pires, with the 7th Battalion of Caçadores, the 1st Battalion of the 10th Infantry Regiment and the "Auxiliary Forces Battalion Group", consisting of the 8th and 9th ACs.

- They were members of a detachment formed by the "1st Cavalry Regiment and the Group of Battalions of Auxiliary Forces [...] and incorporated into another detachment, of which colonel Francelino Cezar de Vasconcelos was commander" (Ribeiro 1953, pp. 351–352).

- Initially made up of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment and the 18th Auxiliary Corps and later added by the 26th Auxiliary Corps and the 2nd Battery of the 6th Horse Artillery Regiment (Ribeiro 1953, p. 354).

- The testimony of the legalist commander, transcribed in Ribeiro 1953, says 24, date seconded by Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022. Other sources, such as Meirelles 2002, Vitor 2021 and Aragão 2021, say 27.

References

Citations

- CPDOC FGV 2015, MEDEIROS, Borges de, p. 16.

- Vitor 2021, p. 59-62.

- Forno 2017, p. 162.

- Ferreira 1993, p. 21.

- Vitor 2021, p. 93.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 209-210.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 274-275.

- Forno 2017, p. 160-163.

- Vitor 2021, p. 64.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 291-292.

- Aragão 2021, p. 130-131.

- Forno 2017, p. 169-170.

- Forno 2017, p. 166.

- Vitor 2021, p. 125-126, 152, 430.

- Aragão 2021, p. 52-53.

- Vitor 2021, p. 94.

- Vitor 2021, p. 430, 435.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 292.

- Alves 2014, p. 20.

- Aragão 2011, p. 175.

- Aragão 2021, p. 160-162.

- Aragão 2021, p. 160.

- Forno 2017, p. 164.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 223-224.

- Karnikowski 2010, p. 452.

- Forno 2017, p. 163-165.

- Vitor 2021, p. 93-95.

- Castro 2016, p. 73-74.

- Vitor 2021, p. 94-96.

- Doria 2016, cap. 22.

- Savian 2020, p. 116.

- Silva 1971, p. 45.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 246.

- Aragão 2021, p. 165-166.

- Vitor 2021, p. 95-96.

- Castro 2016, p. 12.

- Savian 2020, p. 131.

- Vitor 2021, p. 111-113, 117.

- Vitor 2021, p. 173.

- Vitor 2021, p. 96.

- Vitor 2021, p. 138-139.

- Vitor 2021, p. 121-122, 126.

- Caggiani 1997, p. 23.

- Vitor 2021, p. 134.

- Vitor 2021, p. 132.

- Caggiani 1997, p. 23-24.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 222.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 291.

- Vitor 2021, p. 121.

- Vitor 2021, p. 124.

- Vitor 2021, p. 127, 435.

- Vitor 2021, p. 125.

- Vitor 2021, p. 128-129, 433.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 293.

- Silva 1971, p. 48-49.

- Aragão 2021, p. 168-170.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 326.

- Silva 1971, p. 49.

- Aragão 2021, p. 167.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 448.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 273.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 295.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 266, 284.

- Carneiro 1965, p. 290.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 297.

- Silva 1971, p. 51.

- Aragão 2021, p. 171-172.

- Carneiro 1965, p. 291.

- Aragão 2021, p. 168.

- Vitor 2021, p. 120-121.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 294-295.

- Savian 2020, p. 132.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 300-301.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 311.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 265.

- Vitor 2021, p. 130.

- Karnikowski 2010, p. 125-126.

- Teixeira 2018, p. 91-93.

- Vitor 2021, p. 118-120.

- CPDOC FGV 2015, CAMPOS, Siqueira, p. 8-9.

- Vitor 2021, p. 135.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 224.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 351.

- Silva 1971, p. 46-47.

- CPDOC FGV 2015, ALBERTO, João, p. 2.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 223.

- Silva 1971, p. 47.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 294.

- Silva 1971, p. 47-48.

- Donato 1987, p. 202.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 295.

- Silva 1971, p. 50.

- Vitor 2021, p. 130-131.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 296.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 298-302.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 225.

- Vitor 2021, p. 131.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 304-305.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 305-307.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 311-316.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 284.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 297-298.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 337.

- Caggiani 1997, p. 26.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 298.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 334.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 294.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 271-275.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 298.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 299.

- Caggiani 1997, p. 26-27.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 337-342.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 299-300.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 363-364.

- Vitor 2021, p. 112-115.

- CPDOC FGV 2015, ARANHA, Oswaldo, p. 5.

- Vitor 2021, p. 133.

- Savian 2020, p. 133.

- Donato 1987, p. 324.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 303.

- Aragão 2021, p. 175.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 295-297.

- Doria 2016, cap. 13.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 302-304.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 303.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 347.

- Aragão 2021, p. 177.

- Vitor 2021, p. 143-144.

- Muxfeldt & Giorgis 2022, p. 299.

- Silva 1971, p. 69.

- Vitor 2021, p. 143.

- Teixeira 2018, p. 98.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 296-297.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 346.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 305-306.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 226.

- Teixeira 2018, p. 99.

- Silva 1971, p. 68.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 348-349.

- Vitor 2021, p. 147-148.

- Vitor 2021, p. 148-149.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 359-360.

- Teixeira 2018, p. 100.

- Savian 2020, p. 151.

- Vitor 2021, p. 149.

- Teixeira 2018, p. 101.

- Heller 2006, p. 121-122.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 325-326.

- Aragão 2021, p. 179-180.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 364-368.

- Vitor 2021, p. 150.

- "História Completa de Mondaí". Prefeitura de Mondaí. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- Ribeiro 1953, p. 371.

- Vitor 2021, p. 152-153.

- Meirelles 2002, p. 344.

- Savian 2020, p. 151-152.

- Teixeira 2018, p. 101-102.

- Savian 2020, p. 153-155.

- Savian 2020, p. 177-178.

- Silva 1971, p. 73.

- Castro 2016, p. 60, 151.

- Cunha 2013.

- Gaudêncio 2021, p. 110-113.

- Vitor 2021, p. 148.

- Cunha 2013, p. 5.

- Vitor 2021, p. 431.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 228.

- Aragão 2021, p. 183.

- Gaudêncio 2021, p. 108.

- Vitor 2021, p. 137.

- Aragão 2021, p. 217-232.

- Forno 2017, p. 170.

- Bento & Giorgis 1995, p. 229.

- Vitor 2021, p. 143-145.

- Vitor 2021, p. 424-432.

- Vitor 2021, p. 354.

Bibliography

- Alves, Eduardo Henrique de Souza Martins (2014). "As revoltas militares de 1924 no Estado de São Paulo e no Sul do Brasil e a" Guerra Intestina" movida pelos tenentes". A Defesa Nacional. Vol. 101, no. 824.

- Aragão, Isabel Lopez (2011). Da caserna ao cárcere - uma identidade militar-rebelde construída na adversidade, nas prisões (1922-1930) (PDF) (Masters thesis). Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

- Aragão, Isabel Lopez (2021). Identidade militar-revoltosa e exílio: perseguição, articulação e resistência (1922-1930) (PDF) (Doctorate thesis). Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

- Bento, Cláudio Moreira; Giorgis, Luiz Ernani Caminha (1995). História da 3ª Região Militar 1889 -1953 (PDF) (2 ed.). Porto Alegre: AHIMTB.

- Carneiro, Glauco (1965). História das revoluções brasileiras 1.º volume: da revolução da República à Coluna Prestes (1889/1927). Rio de Janeiro: O Cruzeiro.

- Castro, Maria Clara Spada de (2016). Além da Marcha: a (re) formação da Coluna Miguel Costa - Prestes (PDF) (Masters thesis). Universidade Federal de São Paulo.

- Caggiani, Ivo (1997). 2º Regimento da Brigada Militar (2º RPMon) - O Heróico (PDF). Sant' Ana do Livramento: Edigraf.

- CPDOC FGV (2015). Dicionário da Elite Política Republicana (1889-1930). Rio de Janeiro: Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022.

- Cunha, Paulo Ribeiro da (2013). "Um enigma e sua esfinge". Novos Rumos. 50 (1).

- Donato, Hernâni (1987). Dicionário das batalhas brasileiras – dos conflitos com indígenas às guerrilhas políticas urbanas e rurais. São Paulo: IBRASA.

- Doria, Pedro (2016). Tenentes: a guerra civil brasileira (1 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Record.

- Ferreira, Marieta de Moraes (1993). "A Reação Republicana e a crise política dos anos 20". Estudos Históricos. Rio de Janeiro. 6 (11): 9–23.

- Forno, Rodrigo dal (2017). "A revolta tenentista de 1924 e a participação da Aliança Libertadora no Rio Grande do Sul". Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico do Rio Grande do Sul. No. 153.

- Gaudêncio, Bruno Rafael de Albuquerque (2021). A política da memória na construção biográfica de Luiz Carlos Prestes (1945-2015) (PDF) (Doctorate thesis). Universidade de São Paulo.

- Karnikowski, Romeu Machado (2010). De exército estadual à polícia-militar: o papel dos oficiais na 'policialização' da Brigada Militar (1892-1988) (PDF) (Doctorate thesis). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

- Meirelles, Domingos João (2002). As noites das grandes fogueiras: uma história da Coluna Prestes (9 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Record.

- Muxfeldt, Virgílio Ribeiro; Giorgis, Luiz Ernani Caminha (2022). O Exército Republicano (PDF). Porto Alegre: Renascença.

- Heller, Milton Ivan (2006). De Catanduvas ao Oiapoque: o martírio de rebeldes sem causa. Curitiba: Instituto Histórico e Geográfico do Paraná.

- Ribeiro, Aldo Ladeira (1953). Esboço histórico da Brigada Militar do Rio Grande do Sul v. 2 (1918-1930) (PDF) (1 ed.). Porto Alegre: MBM.

- Savian, Elonir José (2020). Legalidade e Revolução: Rondon combate tenentistas nos sertões do Paraná (1924/1925). Curitiba: edição do autor.

- Silva, Hélio (1971). 1926: a Grande Marcha (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

- Teixeira, Eduardo Perez (2018). A Coluna Prestes vista por O Paíz e o Correio da Manhã (1924 - 1927) (PDF) (Masters thesis). Universidade de Brasília. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2023.

- Vitor, Amilcar Guidolim (2021). A Coluna Prestes: disputas em torno do passado e construção do patrimônio cultural sul-rio-grandense (PDF) (Doctorate thesis). Universidade Federal de Santa Maria.