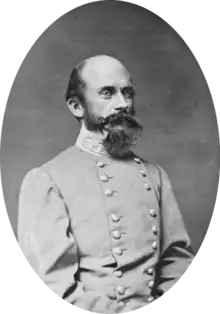

Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell (February 8, 1817 – January 25, 1872) was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee and fought effectively through much of the war. Still, his legacy was clouded by controversies over his actions at the Battle of Gettysburg and the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

Richard Stoddert Ewell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Old Bald Head Baldy |

| Born | February 8, 1817 Georgetown, D.C. |

| Died | January 25, 1872 (aged 54) Spring Hill, Tennessee |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1840–1861 (USA) 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank | Lieutenant General (CSA) |

| Commands held | Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations | Benjamin S. Ewell (brother) Benjamin Stoddert (grandfather) |

Early life and career

Ewell was born in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. He was raised in Prince William County, Virginia, from the age of 3, at an estate near Manassas known as "Stony Lonesome."[1] He was the third son of Dr. Thomas and Elizabeth Stoddert Ewell; the grandson of Benjamin Stoddert, the first United States Secretary of the Navy; the grandson of Revolutionary War Colonel Jesse Ewell; and the brother of Benjamin Stoddert Ewell.[2] He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1840, thirteenth in his class of 42 cadets. His friends called him "Old Bald Head" or "Baldy." He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Dragoons and was promoted to first lieutenant in 1845. From 1843 to 1845, he served with Philip St. George Cooke and Stephen Watts Kearny on escort duty along the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails.[3] In the Mexican–American War, serving under Winfield Scott, he was recognized and promoted to captain for his courage at the Battle of Contreras and the Battle of Churubusco. At Contreras, he conducted a nighttime reconnaissance with engineer Captain Robert E. Lee, his future commander.

Ewell served in the New Mexico Territory for some time, exploring the newly acquired Gadsden Purchase with Colonel Benjamin Bonneville. He was wounded in a skirmish with Apaches under Cochise in 1859.[2] In 1860, while in command of Fort Buchanan, Arizona, illness compelled him to leave the West for Virginia to recuperate.[3] He described his condition as "very ill with vertigo, nausea, etc., and now am excessively debilitated[,] having occasional attacks of the ague."[4] Illnesses and injuries would cause difficulties for him throughout the upcoming Civil War.

Civil War

As the nation moved towards war, Ewell had generally pro-Union sentiments.[3] Nevertheless, when his home state of Virginia declared secession, Ewell resigned from the U.S. Army on May 7, 1861, to join the Provisional Army of Virginia. He was appointed a colonel of cavalry on May 9 and was the first officer of field grade wounded in the war at a May 31 skirmish at Fairfax Court House where he was hit in the shoulder.[5] He was promoted to brigadier general in the Confederate States Army on June 17. He commanded a brigade in the (Confederate) Army of the Potomac at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas). Still, his brigade was guarding fords downstream and did not get into the action at all.[6]

Hours after the battle, Ewell proposed to President of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis that for the Confederacy to win the war, enslaved people must be freed and join the ranks of the army; he was also willing to lead black soldiers into battle. But Davis considered that "impossible", and that topic never came up between him and Ewell again. Nevertheless, like Patrick Cleburne, Ewell was one of those few Confederate generals who believed the Confederacy needed all the soldiers it could get, regardless of race.[7]

In late July, Ewell was furious when he heard that his commanding officer, P. G. T. Beauregard, blamed him for not following orders at Bull Run (Manassas) when the orders did not reach him in time.[8]

Ewell inspired his men despite, not because of, his appearance. Historian Larry Tagg using General Richard Taylor's description, described him:[9]

Rather short at 5 feet 8 inches, he had just a fringe of brown hair on an otherwise bald, bomb-shaped head. Bright, bulging eyes protruded above a prominent nose, creating an effect which many likened to a bird—an eagle, some said, or a woodcock—especially when he let his head droop toward one shoulder, as he often did, and uttered strange speeches in his shrill, twittering lisp. He had a habit of muttering odd remarks in the middle of normal conversation, such as "Now why do you suppose President Davis made me a major general anyway?" He could be spectacularly, blisteringly profane. He was so nervous and fidgety he could not sleep in a normal position, and spent nights curled around a camp stool. He had convinced himself that he had some mysterious internal "disease," and so subsisted almost entirely on frumenty, a dish of hulled wheat boiled in milk and sweetened with sugar. A "compound of anomalies" was how one friend summed him up. He was the reigning eccentric of the Army of Northern Virginia, and his men, who knew at first hand his bravery and generosity of spirit, loved him all the more for it.

— Larry Tagg, The Generals of Gettysburg

With Stonewall Jackson

Ewell was promoted to major general and division command on January 24, 1862. When Joe Johnson's army pulled out of the Manassas area in March and went down to Richmond, Ewell's division was stationed around Culpeper. In May, he was ordered to the Shenandoah Valley to reinforce "Stonewall" Jackson. Ewell moved west, crossing the Blue Ridge, and managed to locate Jackson's command after some difficulty. Although the two generals worked together well and were noted for their quixotic personal behavior, they had many stylistic differences. Jackson was stern and pious, whereas Ewell was witty and extremely profane. Jackson was flexible and intuitive on the battlefield, while Ewell, although brave and effective, required precise instructions to function effectively.[10] Ewell was initially resentful about Jackson's tendency to keep his subordinates uninformed about his tactical plans, but he eventually adjusted to Jackson's methods.

Ewell superbly commanded a division in Jackson's small army during the Valley Campaign, personally winning quite a few battles against the larger U.S. armies of Maj. Gens. Nathaniel P. Banks, John C. Frémont, and James Shields at the Battle of Front Royal and First Battle of Winchester, Battle of Cross Keys, and Battle of Port Republic, respectively. Jackson's army was then recalled to Richmond to join Robert E. Lee in protecting the city against Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac in the Peninsula Campaign. Ewell fought conspicuously at Gaines' Mill and saw relatively light action at Malvern Hill. After Lee repelled the U.S. army in the Seven Days Battles, U.S. Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia threatened to attack from the north, so Jackson was sent to intercept him. Ewell defeated Banks again at the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9, and, returning to the old Manassas battlefield, he led his division into action at Brawner's Farm on August 28. A Minie ball shattered Ewell's left leg, and he lay on the ground for several hours before being found and taken away. The leg was amputated above the knee, and Ewell faced a painful recovery lasting months. Although he received a wooden leg, the irregular shape of the leg stump made it difficult to fit it. Ewell slipped and fell in Richmond on Christmas Day, aggravating his injury further.

While recovering from his injury, Ewell was nursed by his first cousin, Lizinka Campbell Brown, a wealthy widow from the Nashville area. Ewell had been attracted to Lizinka since his teenage years, and they had flirted with romance in 1861 and during the Valley Campaign, but now the close contact resulted in their wedding in Richmond on May 26, 1863.[11]

Ewell returned to Lee's Army of Northern Virginia after the Battle of Chancellorsville. After the mortal wounding of Jackson at that battle, on May 23, Ewell was promoted to lieutenant general and command of the Second Corps (now slightly smaller than Jackson's because units were detached to create a new Third Corps, under Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill, also one of Jackson's division commanders). Ewell was given a date of rank one day earlier than Hill's, so he became the third-highest-ranking general in the Army of Northern Virginia, after Lee and James Longstreet.[12]

Gettysburg and controversy

Ewell continued to have difficulty walking and needed crutches when not mounted on horseback. In the opening days of the Gettysburg Campaign, at the Second Battle of Winchester, Ewell performed superbly, capturing the U.S. garrison of 4,000 men and 23 cannons. He escaped severe injury there when he was hit in the chest with a spent bullet (the second such incident in his career, after Gaines' Mill).[2] His corps took the lead in the invasion of Pennsylvania and almost reached the state capital of Harrisburg before being recalled by Lee to concentrate at Gettysburg. These successes led to favorable comparisons with Jackson.

But at the Battle of Gettysburg, Ewell's military reputation started a long decline. On July 1, 1863, Ewell's corps approached Gettysburg from the north and smashed the U.S. XI Corps and part of the I Corps, driving them back through the town and forcing them to take up defensive positions on Cemetery Hill south of town. Lee had just arrived on the field and saw the importance of this position. He sent discretionary orders to Ewell that Cemetery Hill be taken "if practicable." Historian James M. McPherson wrote, "Had Jackson still lived, he undoubtedly would have found it practicable. But Ewell was not Jackson."[13] Ewell chose not to attempt the assault.

Ewell had several possible reasons for not attacking. The orders from Lee contained an innate contradiction. He was "to carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army."[14] Lee also refused to provide assistance that Ewell requested from the corps of A. P. Hill. Ewell's men were fatigued from their lengthy marching and strenuous battle in the hot July afternoon. It would be difficult to reassemble them into battle formation and assault the hill through the narrow corridors afforded by the streets of Gettysburg. The fresh division under Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson was arriving. Still, Ewell also received intelligence that heavy U.S. reinforcements were approaching from the east on the York Pike, potentially threatening his flank.[15] Ewell's normally aggressive subordinate, Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early, concurred with his decision.

Lee's order has been criticized because it left too much discretion to Ewell. Historians such as McPherson have speculated on how the more aggressive Stonewall Jackson would have acted on this order if he had lived to command this wing of Lee's army and how differently the second day of battle would have proceeded with Confederate possession of Culp's Hill or Cemetery Hill. Discretionary orders were customary for General Lee because Jackson and James Longstreet, his other principal subordinate, usually reacted to them very well and could use their initiative to respond to conditions and achieve the desired results. Ewell's critics have noted that this failure of action on his part, whether justified or not, ultimately cost the Confederates the battle.[16] Other historians have noted that Lee, as the overall commanding general who issued discretionary orders to Ewell and then continued the battle for another two days, bears the final responsibility for the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg.[17]

When Ewell's corps attacked these positions on July 2 and 3, the U.S. army had had time to fully occupy the heights and build impregnable defenses, resulting in heavy Confederate losses. Postwar proponents of the Lost Cause movement, particularly Jubal Early, but also Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble, assigned to Ewell's staff during the battle, criticized him bitterly to deflect any blame for losing the battle on Robert E. Lee. Part of their argument was that the U.S. soldiers were demoralized by their defeat earlier in the day. Still, Ewell's men were also disorganized, and their decisions were far simpler to make in hindsight than in the heat of battle and fog of war.[18]

On July 3, Ewell was again wounded, but only in his wooden leg. He led his corps on an orderly retreat back to Virginia. By late November, Ewell took a leave of absence due to fever and continued problems with his leg. Within a month, he returned to command but struggled with his health and mobility. He was bruised in a fall from his horse in January 1864.

Overland Campaign and Richmond

Ewell led his corps in the May 1864 Battle of the Wilderness and performed well, enjoying a slight numerical superiority over the U.S. corps that attacked him. In the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Lee felt compelled to lead the defense of the "Mule Shoe" on May 12 personally because of Ewell's indecision and inaction. At one point, Ewell began hysterically berating some of his fleeing soldiers and beating them over the back with his sword. Lee reined him in, saying sharply, "General Ewell, you must restrain yourself; how can you expect to control these men when you have lost control of yourself? If you cannot repress your excitement, you had better retire." Ewell's behavior on this occasion undoubtedly was the source of a statement made by Lee to his secretary, William Allan, after the war that on May 12, he "found Ewell perfectly prostrated by the misfortune of the morning, and too much overwhelmed to be efficient."[19] In the final combat at Spotsylvania, on May 19, 1864, Ewell ordered an attack on the U.S. left flank at the Harris Farm, which had little effect beyond delaying Grant for a day, at the cost of 900 casualties, about one-sixth of his remaining force.[20]

Lee felt that Ewell was not in any shape for field command and decided to reassign him to the Richmond defenses. In April 1865, as Ewell and his troops were retreating, many fires in Richmond were started, although it is unclear by whose orders the fires were started.[21] Ewell blamed the plundering mobs of civilians for burning a tobacco warehouse, which was a significant source of the fire, but Nelson Lankford, the author of Richmond Burning, wrote that "Ewell convinced few people that the great fire had nothing to do with his men or their deliberate demolition of the warehouses and bridges through military orders passed down the chain of command."[22] These fires created The Great Conflagration of Richmond, which left a third of the city destroyed, including all of the business district.[23] Ewell and his troops were then surrounded and captured at Sailor's Creek. This was a few days before Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House. Ewell told his captors that he had no idea what Lee was planning to do next, but the Confederacy was clearly doomed, and he hoped he would have the sense to surrender. He was held as a prisoner of war at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor until July.

While imprisoned, Ewell organized a group of sixteen former generals also at Fort Warren, including Edward "Allegheny" Johnson and Joseph B. Kershaw, and sent a letter to Ulysses S. Grant about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, for which they said no Southern man could feel anything other than "unqualified abhorrence and indignation" and insisting that the crime should not be connected to the southern states.[24]

Postbellum life

After his parole, Ewell retired to work as a "gentleman farmer" on his wife's farm near Spring Hill, Tennessee, which he helped to become profitable, and also leased a successful cotton plantation in Mississippi. His leg stump had largely healed by the war's end and no longer seriously bothered him, but he continued to suffer from neuralgia and other ailments. He doted on Lizinka's children and grandchildren. He was president of the Columbia Female Academy's board of trustees, a communicant at St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Columbia, and president of the Maury County Agricultural Society.[25] Ewell and his wife came down with pneumonia in January 1872 and died within a few days of each other.[26] They were buried in Old City Cemetery in Nashville, Tennessee. He is the author of The Making of a Soldier, published posthumously in 1935.

In popular media

Tim Scott portrayed Ewell in the 1993 film Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara's novel, The Killer Angels. In that movie, Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble meets with Robert E. Lee and tells him that Ewell had refused to take Cemetery Hill, giving the U.S. army a massive advantage, and that many men would die in the coming days because of that failure.

Ewell is the main character in the 1963 gospel film Red Runs the River and is portrayed by Bob Jones Jr. The film, directed by Katherine Stenholm, details Ewell's relationship with Stonewall Jackson and Ewell's conversion to Christ following his wound at the Second Battle of Bull Run (Manassas). It is an Unusual Films production from the Cinema Department of Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina.[27] Red Runs the River was the film the University Film Producers Association selected to represent the United States at the International Congress of Motion-Picture and Television Schools in Budapest, Hungary.[28]

Notes

- Pfanz, p. 6.

- Eicher, p. 229.

- Fredriksen, p. 664.

- Pfanz, p. 119.

- Pfanz, p. 124–128.

- Pfanz, p. 135–141.

- Pfanz, p. 139

- Pfanz, pp. 135–140.

- Tagg, p. 251.

- Fredriksen, p. 665.

- Pfanz, p. 275.

- Pfanz, p. 273.

- McPherson, p. 654.

- Sears, p. 227.

- Sears, p. 228.

- Fredriksen, p. 665. A recent summary of Ewell's decision and the feasibility of an assault can be found in Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White, "Richard Ewell at Gettysburg," Civil War Times, August 2010.

- Elizabeth Brown Pryor, "Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through Private Letters," p. 359. Also see Emory Thomas, "Robert E. Lee," p. 303.

- Coddington, pp. 318-19.

- Pfanz, p. 389.

- Rhea, p. 187; Pfanz, p. 393.

- George, J et al., Abraham Lincoln, 1890, pp. 205-06

- Lankford, p. 107.

- Ripley, G. et al., The American Cyclopaedia, 1883, p. 237.

- "Letter to Lt. Gen. Grant, April 16, 1865." The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Washington, DC; Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), v. 46, Part 3, 787.

- Pfanz, p. 489.

- Pfanz, p. 494.

- Red Runs the River at IMDB.

- Katherine Stenholm biography at IMDB.

References

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 978-0-684-84569-2.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Frederiksen, John C. "Richard Stoddert Ewell." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Lankford, Nelson. Richmond Burning: The Last Days of the Confederate Capital. New York: Viking, 2002. ISBN 0-670-03117-8.

- Pfanz, Donald C. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier's Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8078-2389-9.

- Rhea, Gordon C. To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee, May 13–25, 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8071-2535-0.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.