Rhynchosaur

Rhynchosaurs are a group of extinct herbivorous Triassic archosauromorph reptiles, belonging to the order Rhynchosauria.[1] Members of the group are distinguished by their triangular skulls and elongated, beak like premaxillary bones. Rhynchosaurs first appeared in the Middle Triassic or possibly the Early Triassic, before becoming abundant and globally distributed during the Carnian stage of the Late Triassic.

| Rhynchosaurs | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

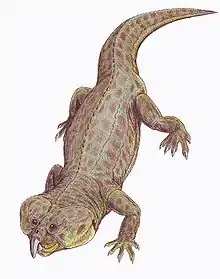

| Life restoration of Hyperodapedon sanjuanensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Order: | †Rhynchosauria Osborn 1903 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Description

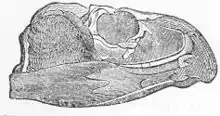

Rhynchosaurs were herbivores, and at times abundant (in some fossil localities accounting for 40 to 60% of specimens found), with stocky bodies and a powerful beak. Early primitive forms, like Mesosuchus and Howesia, were generally small and more typically lizard-like in build, and had skulls rather similar to the early diapsid Youngina, except for the beak and a few other features. Later and more advanced genera grew to medium to medium large size, up to two meters in length. The skull in these forms were short, broad, and triangular, becoming much wider than long in the most advanced forms like Hyperodapedon (= Scaphonyx), with a deep cheek region, and the premaxilla extending outwards and downwards to form the upper beak. The broad skull would have accommodated powerful jaw muscles. The lower jaw was also deep, and when the mouth was closed it clamped firmly into the maxilla (upper jaw), like the blade of a penknife closing into its handle. This scissors-like action would have enabled rhynchosaurs to cut up tough plant material. Rhynchosaur teeth had a unique condition known as ankylothecodonty, similar to the acrodonty of modern tuataras and some lizards but differing in the presence of deep roots.[2]

The teeth were unusual; those in the maxilla and palate were modified into broad tooth plates. The hind feet were equipped with massive claws, presumably for digging up roots and tubers by backwards scratching of the hind limbs. Similar to elephants they had a fixed number of teeth where those further back in the jaws replaced those who were worn out as the animal grew in size and the teeth was worn out because of a diet of very tough plants. In the end they probably starved to death.[3]

Like many animals of this time, they had a worldwide distribution, being found across Pangea. These abundant animals might have died out suddenly at the end of the Carnian (Middle of the Late Triassic period), perhaps as a result of the extinction of the Dicroidium flora on which they may have fed. On the other hand, Spielmann, Lucas and Hunt (2013) described three distal ends of humeri from early-mid Norian Bull Canyon Formation in New Mexico, which they interpreted as bones of rhynchosaurs belonging to the species Otischalkia elderae; thus, the fossils might indicate that rhynchosaurs survived until the Norian.[4]

Classification

Taxonomy

| Genera | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Age | Location | Unit | Notes | |

|

A. navajoi |

||||||

|

B. cooowuse |

||||||

|

B. mariantensis |

Previously known as the "Mariante Rhynchosaur". | |||||

|

B. sidensis |

late Anisian |

|||||

| Elorhynchus | E. carrolli | late Ladinian? - earliest Carnian? | Chañares Formation | |||

|

E. wolvaardti |

early Anisian |

|||||

|

F. spenceri |

late Anisian |

|

||||

|

H. browni |

||||||

|

H. gordoni |

Six valid species has been named, the most of any rhynchosaur. | |||||

|

H. huenei |

||||||

|

H. huxleyi |

||||||

|

H. mariensis |

||||||

|

H. sanjuanensis |

||||||

|

H. tikiensis |

||||||

|

I. genovefae |

Makay Formation (Isalo II) |

|||||

|

M. kuttyi |

||||||

|

L. brodiei |

|

|||||

|

M. browni |

||||||

|

N. colletti |

early Induan |

The earliest known species, and the only Early Triassic representative.[6] | ||||

|

O. bairdi |

||||||

|

R. articeps |

|

|||||

|

S. stockleyi |

late Anisian |

|||||

|

S. stockleyi |

Tunduru district |

|||||

|

T. sulcognathus |

early Norian |

The latest surviving species, and the only Norian rhynchosaur. | ||||

Phylogeny

The Rhynchosauria included a single family, named Rhynchosauridae. All rhynchosaurs, apart from the four Early and Middle Triassic monospecific genera, Eohyosaurus, Mesosuchus, Howesia and Noteosuchus, are included in this family.[6] Hyperodapedontidae named by Lydekker (1885) was considered its junior synonym.[7] However, Langer et al. (2000) noted that Hyperodapedontidae was erected by Lydekker to include Hyperodapedon gordoni and H. huxleyi, clearly excluding Rhynchosaurus articeps, which was the only other rhynchosaur known at that time. Thus, they defined it as the stem-based taxon that includes all rhynchosaurs more closely related to Hyperodapedon than to Rhynchosaurus.[8]

Within Hyperodapedontidae, which is now a subgroup of Rhynchosauridae, two subfamilies have been named. Stenaulorhynchinae named by Kuhn (1933) is defined sensu Langer and Schultz (2000) to include all species more closely related to Stenaulorhynchus than to Hyperodapedon. Hyperodapedontinae named by Chatterjee (1969) was redefined by Langer et al. (2000) to include "all rhynchosaurs closer to Hyperodapedon than to "Rhynchosaurus" spenceri" (now Fodonyx).[9]

The cladogram below is based on Schultz et al. (2016) which is the most genera inclusive rhynchosaur phylogenetic analysis to date,[9] with the position of Noteosuchus taken from other recent analyses (since it was removed in Schultz et al. (2016)), all in consensus with one another.[6][10]

| Rhynchosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Ezcurra, Martín D.; Montefeltro, Felipe; Butler, Richard J. (2016). "The Early Evolution of Rhynchosaurs". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 3. doi:10.3389/fevo.2015.00142. ISSN 2296-701X.

- Sethapanichsakul, Thitiwoot; Coram, Robert A.; Benton, Michael J. (2023). "Unique dentition of rhynchosaurs and their two‐phase success as herbivores in the Triassic". Palaeontology. 66 (3). doi:10.1111/pala.12654.

- Ancient herbivore's diet weakened teeth and lead to eventual starvation, suggests study

- Justin A. Spielmann; Spencer G. Lucas & Adrian P. Hunt (2013). "The first Norian (Revueltian) rhynchosaur: Bull Canyon Formation, New Mexico, U.S.A." (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 61: 562–566.

- Fitch, A. J.; Haas, M.; C'Hair, W.; Ridgley, E.; Ridgley, B.; Oldman, D.; Reynolds, C.; Lovelace, D. M. (2023). "A New Rhynchosaur Taxon from the Popo Agie Formation, WY: Implications for a Northern Pangean Early-Late Triassic (Carnian) Fauna". Diversity. 15 (4): 544. doi:10.3390/d15040544. hdl:10919/114487.

- Richard J. Butler; Martín D. Ezcurra; Felipe C. Montefeltro; Adun Samathi & Gabriela Sobral (2015). "A new species of basal rhynchosaur (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha) from the early Middle Triassic of South Africa, and the early evolution of Rhynchosauria". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 174 (3): 571–588. doi:10.1111/zoj.12246. hdl:11449/167867.

- Benton, M. J. (1985). "Classification and phylogeny of the diapsid reptiles". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 84 (2): 97–164. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1985.tb01796.x.

- Max C. Langer & Cesar L. Schultz (2000). "A new species of the Late Triassic rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon from the Santa Maria Formation of south Brazil". Palaeontology. 43 (6): 633–652. Bibcode:2000Palgy..43..633L. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00143. S2CID 83566087.

- Cesar Leandro Schultz; Max Cardoso Langer & Felipe Chinaglia Montefeltro (2016). "A new rhynchosaur from south Brazil (Santa Maria Formation) and rhynchosaur diversity patterns across the Middle-Late Triassic boundary". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 90 (3): 593–609. doi:10.1007/s12542-016-0307-7. hdl:11449/161986. S2CID 130644209.

- Ezcurra MD. (2016) The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms. PeerJ, 4:e1778

Bibliography

- Benton, M. J. (2000), Vertebrate Paleontology, 2nd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd.

- Carroll, R. L. (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, W.H. Freeman & Co.

- Dilkes, D. W. 1998. The Early Triassic rhynchosaur Mesosuchus browni and the interrelationships of basal archosauromorph reptiles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: Biological Sciences, 353:501-541.