Reza Abbasi

Reza Abbasi (Persian: رضا عباسی),[lower-alpha 1] also known as Aqa Reza (c. 1565 – 1635),[lower-alpha 2] was the leading Persian miniaturist of the Isfahan School during the later Safavid period, spending most of his career working for Shah Abbas I.[1] He is considered to be the last great master of the Persian miniature, best known for his single miniatures for muraqqa or albums, especially single figures of beautiful youths.

Reza Abbasi | |

|---|---|

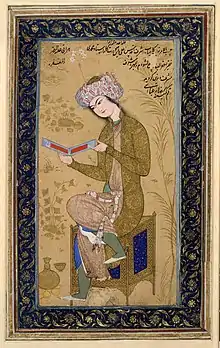

Posthumous portrait of Reza Abbasi by his student Mo'en Mosavver. Created in Isfahan on 19 April 1676 | |

| Born | 1565 |

| Died | 1635 (aged 69–70) Tabriz, Safavid Iran |

| Family | Ali Asghar (father) |

Life and art

Riza was possibly born in Kashan, as Āqā Riżā Kāshānī is one of the versions of his name; it has also been suggested that he was born in Mashad, where his father, the miniature artist Ali Asghar, is recorded as having worked in the atelier of the governor, Prince Ibrahim Mirza.[2] After Ibrahim's murder, Ali Asghar joined Shah Ismail II's workshop in the capital Qasvin.[3] Riza probably received his training from his father and joined the workshop of Shah Abbas I at a young age. By this date, the number of royal commissions for illustrated books had diminished, and had been replaced by album miniatures in terms of employment given to the artists of the royal workshop.[4]

Unlike most earlier Persian artists, he typically signed his work, often giving dates and other details as well, though there are many pieces with signatures that scholars now reject.[5] He may have worked on the ambitious, but incomplete Shahnameh, now in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin.[6] A much later copy of the work, from 1628, at the end of Abbas' reign and rendered in a very different style, may also be his. It is now in the British Library (MS Additional 27258).[7] His first dated drawing is from 1601, in the Topkapi Palace.[8] A book miniature of 1601–2 in the National Library of Russia has been attributed to him; the only other miniature in the book is probably by his father.[9] He is generally attributed with the 19 miniatures in a Khusraw and Shirin of 1631–32, although their quality has been criticised.[10]

His speciality, however, was the single miniature for the albums or muraqqas of private collectors, typically showing one or two figures with a lightly drawn garden background, sometimes in gold, in the style formerly used for border paintings, with individual plants dotted about on a plain background. These vary between pure pen drawings and fully painted subjects with colour throughout, with several intermediate varieties. The most typical have at least some colour in the figures, though not in the background; later works tend to have less colour. His, or his buyers', favourite subjects were idealized figures of stylishly dressed and beautiful young men. According to Barbara Brend:

The line of Riza's ink drawings has an absolute mastery conveying texture, form, movement and even personality. His coloured figures, which must often be portraits, are more restrained and lay more emphasis on the fashions of the day, the rich textiles, the carelessly draped turban, the European hat. Effete figures are often presented standing in a curved posture which accentuates their well-fed waists.[11]

The style he pioneered remained influential on subsequent generations of Persian painters; several pupils were prominent artists, including Mo'en Mosavver, who painted his portrait many decades later (illustrated at top) as well as Riza's son, Muhammed Shafi Abbasi.[12]

His earlier works were signed Aqa Risa (or Riza, Reza etc., depending on the transliteration used), which, confusingly, is also the name of a contemporary Persian artist who worked for the Mughal Emperor Jahangir in India. In 1603, at the age of about 38, the artist in Persia received the honorific title of Abbasi from his patron, the shah, associating him with his name. In the early 20th century, there was much scholarly debate, mostly in German, as to whether the later Aqa Risa and Riza Abbasi were the same figures. It is now accepted that they were, although his style shows a considerable shift in mid-career.[13] Riza Abbasi, the painter, is also not to be confused with his contemporary Ali Riza Abbasi, Shah Abbas' favourite calligrapher, who in 1598, was appointed to the important position of royal librarian, and therefore in charge of the royal atelier of painters and calligraphers. Both Rizas accompanied the shah on his campaign to Khurasan in 1598 and followed him to the new capital he established in Isfahan from 1597 to 1598.[14] Soon after, Riza Abbasi left the Shah's employ in a "mid-life crisis",[15] apparently seeking greater independence and freedom to associate with Isfahan's "low-life" world, including athletes, wrestlers and other unrespectable types.[16] In 1610, he returned to the court, probably because he was short of money, and continued in the employ of the Shah until his death.[17] A series of drawings copying the miniatures attributed to the great 15th-century artist Behzad, which were in the library of the shrine at Ardabil, strongly suggest that Riza had visited the city, probably as part of the Shah's party and perhaps on his visits in 1618 or 1625.[18]

About the time of his return to court service, there is a considerable change in his style. "The primary colours and virtuoso technique of his early portraits give way in the 1620s to darker, earthier colours and a coarser, heavier line. New subjects only partly compensate for this disappointing stylistic development".[19] He painted many older men, perhaps scholars, Sufi divines, or shepherds, as well as birds and Europeans, and in his last years sometimes satirized his subjects.[20]

Sheila Canby's 1996 monograph accepts 128 miniatures and drawings as by Riza, or probably so, and lists as "Rejected" or "Uncertain Attributions" a further 109 that have been ascribed to him at some point[21] Today, his works can be found in Tehran in the Reza Abbasi Museum and in the library at the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. They can also be found in several western museums, such as the Smithsonian, where the Freer Gallery of Art has an album of works by him and pupils,[22] the British Museum, Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gallery

Reclining woman, 1595

Reclining woman, 1595.jpg.webp) Two Lovers, 1630

Two Lovers, 1630 Youth kneeling and holding out a wine cup

Youth kneeling and holding out a wine cup Prince Muhammad-Beik of Georgia by Reza Abbasi, 1620

Prince Muhammad-Beik of Georgia by Reza Abbasi, 1620 Cup-bearer. Miniature

Cup-bearer. Miniature Young Portuguese

Young Portuguese Musician dressed as a European with viol

Musician dressed as a European with viol Young man with a sword

Young man with a sword Lady with a Fan

Lady with a Fan

Notes

- also spelled Riza yi-Abbasi or Reza-e Abbasi

- Āqā Riżā Kāshānī

References

- Brend, 165

- Grove

- Titley, 108

- Brend, 165-166: Grove

- Canby (1996), Appendix III and passim

- Canby (1996), 181, allows him four of the miniatures

- Titley, 108-109, 114

- Grove

- Canby (2009), 176

- Canby (1996), 193, items 75-93

- Brend, 165-166

- Grove

- Titley, 114; Grove; Gray, 80-81 represents an older view

- Canby (2009), 36; see also the calligrapher's biography in Encyclopedia Iranica

- Grove

- Grove; Brend, 165; Titley, 114. Both contemporary sources and the female scholars who dominate the study of the Persian miniature show little patience with Riza's mid-life interlude.

- Titley, 114; Brend 165; Canby (2009), 36, 50

- Canby (2009), 123, 179

- Grove

- Grove

- Canby (1996), Appendices I & III

- Titley, 114

Bibliography

- Brend, Barbara. Islamic art, Harvard University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-674-46866-X, 9780674468665

- "Canby (2009)",Canby, Sheila R. (ed). Shah Abbas; The Remaking of Iran, 2009, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-2452-0

- "Canby (1996)", Canby, Sheila R, Rebellious Reformer: The Drawings and Paintings of Riza Yi-Abbasi of Isfahan, 1996, Tauris IB.

- Gray, Basil, Persian Painting, Ernest Benn, London, 1930

- "Grove" - Canby, Sheila R., Riza [Riżā; Reza; Āqā Riżā; Āqā Riżā Kāshānī; Riżā-yi ‛Abbāsī], in Oxford Art Online (subscription required), accessed 5 March 2011

- Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India, 1983, University of Texas Press, 0292764847

External links

- Canby, Sheila R. (1995). "Riḍā ʿAbbāsī". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian

- Persian drawings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Abbasi