List of regional characteristics of Romanesque churches

Romanesque is the architecture of Europe which emerged in the late 10th century and evolved into Gothic architecture during the 12th century. The Romanesque style in England is more traditionally referred to as Norman architecture.

The style can be identified across Europe with certain significant architectural features occurring everywhere. There are other characteristics that differ greatly from region to region.

Most of the buildings that are still standing are churches, some of which are very large abbey churches and cathedrals. The majority of these are still in use, some of them having been substantially altered over the centuries.[1]

This list presents a comparison of Romanesque churches, abbeys and cathedrals of different countries. The second section describes the architectural features that can be identified within pictures of major architectural elements.

Romanesque architecture, regional characteristics

Features of Romanesque architecture that is seen in different areas around Europe.

- Small churches are generally without aisles, with a projecting apse.

- Large churches are basilical with a nave flanked by aisles and divided by an arcade.[2]

- Abbey churches and cathedrals often had transepts.[2]

- Round arches in arcades, windows, doors and vaults.[3]

- Massive walls.[3]

- Towers.[2]

- Piers.[3]

- Stout columns.[3]

- Buttresses of shallow projection.[3]

- Groin vaulting.[3]

- Portals with sculpture and mouldings.[3]

- Decorative arcades as an external feature, and frequently internal also.[3]

- Cushion capitals.[3]

- Murals.[3]

Features which are regionally diversified

These features often have strong local and regional traditions. However, the movement of senior clergy, stonemasons and other craftsmen meant that these traditional features are sometimes found at distant locations.

Romanesque churches in Italy

Atrium of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, in Milan

Atrium of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, in Milan Facade of the Basilica of San Michele Maggiore, in Pavia

Facade of the Basilica of San Michele Maggiore, in Pavia Pisa Cathedral showing polychrome, galleries, dome (completed later), and free-standing campanile

Pisa Cathedral showing polychrome, galleries, dome (completed later), and free-standing campanile San Zeno, Verona, showing defined facade, porch and wheel window

San Zeno, Verona, showing defined facade, porch and wheel window West front of Trani Cathedral, with bell tower

West front of Trani Cathedral, with bell tower Front of Basilica di San Nicola, in Bari

Front of Basilica di San Nicola, in Bari

Influences

- Pre-Romanesque is demonstrated in Italy by the construction of churches with thick walls of undressed stone, very small windows and massive fortresslike character.

- Early Christian and Italian Byzantine architecture formed a stylistic link with the architecture of Ancient Rome, through which the basilica plan and the Classical form of column were transmitted.[2]

- The architecture of Northern Italy has features in common with French and German Romanesque.[2]

- The architecture of Southern Italy and Sicily was influenced by both Norman and Islamic architecture.[2]

- Building stone was available in mountainous regions, while brick was employed for most building in river valleys and plains. The availability of marble had a profound effect on the decoration of buildings.[4]

- The existence and continuance of local rather than unified rule meant the construction and continued existence of many Romanesque civic buildings, and a large number of cathedrals.

- A great many religious buildings of this period remain, many of them little altered. Other buildings include fortifications, castles, civic buildings, and innumerable domestic buildings that are often much altered.

Modena Cathedral showing tri-apsidal eastern end, shallow transepts and square campanile

Modena Cathedral showing tri-apsidal eastern end, shallow transepts and square campanile Interior of the Baptistery of St John, Florence, showing polychrome marble veneer and gold mosaics

Interior of the Baptistery of St John, Florence, showing polychrome marble veneer and gold mosaics

Bari Cathedral, showing shallow apse, domed crossing, Corinthianesque columns and maetreum gallery

Bari Cathedral, showing shallow apse, domed crossing, Corinthianesque columns and maetreum gallery The Church of Sant'Ambrogio, Milan, has domical ribbed vaults and a contrasting red brick and stone.

The Church of Sant'Ambrogio, Milan, has domical ribbed vaults and a contrasting red brick and stone.

Characteristics

- Large churches often have basilical form, with a projecting apse.[4]

- Some large churches have projecting transepts as at Pisa Cathedral.[5]

- Towers are freestanding and may be circular as at Pisa.[5]

- Windows are small.[6]

- The façade takes two forms, that which coincides with the basilical section of nave and aisles, as at Pisa Cathedral and that which screens the form, such as San Michele, Pavia.[6]

- Dwarf galleries are the prevalent form of decoration on the façade as at Pisa Cathedral.[4]

- A number of churches have facades and interiors that are faced with polychrome marble, as at San Miniato al Monte.[4] The rest of a brick exterior was generally left undecorated with some notable exceptions including Pisa Cathedral.[5]

- Portals were rarely large and were square rather than round, as at San Miniato al Monte. Decorative tympanums, where they exist, are mosaic, fresco or shallow relief, as at San Zeno, Verona.[6]

- Shallow relief carving in marble was a feature of some facades, as at San Zeno and Modena Cathedral

- Ocular and Wheel windows are commonly found in facades, as at San Zeno and Modena Cathedral.[6]

- Portals are sometimes covered by an open porch supported on two columns standing on the backs of lions at San Zeno, Verona.[4]

- Internally, large churches generally have arcades resting on columns of Classical form.[6]

- There is little emphasis on vertical mouldings.[6]

- The wall surface above the arcade was covered with decorative marble, mosaic or fresco.[5] Galleries such as that at Pisa were uncommon, but occur in convent churches as nuns' galleries.

- Open timber roofs prevailed.[6]

- Ribbed vaults, when used, are large, square and domical, spanning two bays as at San Michele, Pavia, and Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio.

- The crossing is often covered by a dome, as at Bari Cathedral and Pisa Cathedral (where the dome is oval and of a later date).[6]

- The choir may be above a vaulted crypt, accessible from the nave or aisles, as at San Zeno, Verona.[6]

- Freestanding polygonal baptisteries were common, as at Parma Cathedral and the Baptistery of San Giovanni, Florence.[4]

- Cloisters often have an array of elaborately twisted columns, and fanciful decoration in mosaic tiles as at the Romanesque cloister of the Ancient Basilica of St Paul's Outside the Walls, Rome.[5]

- The large churches and cathedrals of Southern Italy and Sicily were influenced by Norman architecture, as at Trani Cathedral and Bari Cathedral in Apulia.[4]

- Churches in Sicily were influenced by Islamic architecture, in the employment of the pointed arch as at Monreale Cathedral and Palermo Cathedral.[4]

Notable buildings

- Pisa Cathedral and complex. Tuscany

- Baptistery of Florence, Tuscany

- Basilica of San Miniato al Monte, Tuscany

- Santa Maria della Pieve, Arezzo

- Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, Milan, Northern Italy

- Basilica of San Michele Maggiore, Pavia, Northern Italy

- Basilica of San Zeno, Verona, Northern Italy

- Modena Cathedral, Northern Italy

- Ancona Cathedral, Northern Italy

- San Vittore alle Chiuse, Genga.

- Parma Cathedral and complex, Northern Italy

- Trani Cathedral, Apulia

- Bari Cathedral, Apulia

- Basilica di San Nicola, Apulia

- Palermo Cathedral, Sicily

- Monreale Cathedral, Sicily

- Cefalù Cathedral, Sicily

Romanesque churches in France

Notre-Dame-du-Mont-Cornadore, Saint-Nectaire, Puy-de-Dôme with a polygonal crossing tower like Cluny, flat buttresses and a high eastern apse with radiating low apses forming a chevete.

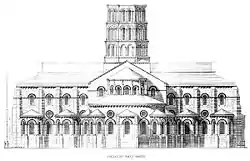

Notre-Dame-du-Mont-Cornadore, Saint-Nectaire, Puy-de-Dôme with a polygonal crossing tower like Cluny, flat buttresses and a high eastern apse with radiating low apses forming a chevete. The Abbey of Saint-Georges, Boscherville, is very typical of Norman architecture of the early 12th century with storeys of identical windows, blind arcading and paired turrets. The facade reveals the form of nave and aisles.

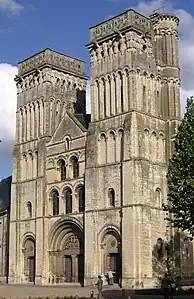

The Abbey of Saint-Georges, Boscherville, is very typical of Norman architecture of the early 12th century with storeys of identical windows, blind arcading and paired turrets. The facade reveals the form of nave and aisles. The Church of the Abbey of la Trinité, Caen shows the development of the twin-tower and triple-portal facade

The Church of the Abbey of la Trinité, Caen shows the development of the twin-tower and triple-portal facade Angouleme Cathedral shows a turreted screen facade which gives little indication of the building's form and is typical of southern France.

Angouleme Cathedral shows a turreted screen facade which gives little indication of the building's form and is typical of southern France. Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, is a typical example of large pilgrimage churches, with double side aisles.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, is a typical example of large pilgrimage churches, with double side aisles.

Influences

- Monastic tradition was a major influence on church architecture with the Abbey Church of Cluny, founded 910 AD, being the largest church in the world at that time.[7]

- The foundation of the Cistercian Order in 1098 introduced a simplicity of design and austerity of ornament.[8]

- Particularly in the south, the existence of Roman structures such as the Pont du Gard played a part in the development of storied arcades and other structural forms.[8]

- Building stone was readily available, including high grade limestone suitable for fine carving.[8]

- For much of the period Normandy were comparatively large and powerful political unit, and developed consistent styles that affected much of northern France.[8]

- South of the Loire Valley churches showed considerable diversity of architectural form and are often without aisles.[8]

- The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain led to the establishment of four pilgrim routes through France, and the establishment of many religious houses along the routes.

- Crusade and pilgrimage brought contact with Islamic and Byzantine architecture that influenced the forms of a number of churches such as Saint-Front, Périgueux.[8]

- The development of ribbed vaulting at Saint-Etienne, Caen, and the adoption of a number of new techniques within a single influential building, the Abbey of Saint-Denis, led to the early employment of the Gothic methods of construction and style from 1140 onwards.[7]

- A great many abbey churches, some of which are now cathedrals or have been elevated to the rank of Minor Basilica, date from this period, and are among the finest architectural works of France. There are also numerous village churches, many of which have remained little changed.

The Church of Saint-Etienne Nevers shows three stages of the nave: arcade, gallery and clerestorey.

The Church of Saint-Etienne Nevers shows three stages of the nave: arcade, gallery and clerestorey. Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe shows a high apse with a clerestorey, and ambulatory with columns of Classical form typical of southern France.

Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe shows a high apse with a clerestorey, and ambulatory with columns of Classical form typical of southern France.

Characteristics

- Large churches of northern have basilical form of nave and aisles separated by arcades.[9]

- Large churches of southern France may be without aisles, as at Angouleme Cathedral.[9]

- Churches generally have transepts.[9]

- The eastern end often takes the form of an apse that is almost as high as the walls.[9]

- The high apse was increasingly surrounded by an ambulatory and later Romanesque churches have a fully developed chevet with radiating chapels.

- In Normandy, two towers on the façade flanking the nave became standard for large churches and influenced the subsequent Romanesque and Gothic facades of Northern France, England, Sicily and other buildings across Europe.

- At the Abbey Church of Cluny, as well as paired towers on the west front, there was a variety of towers large and small. Of these the octagonal tower over the crossing and smaller transept tower remain intact. This arrangement was to influence other churches such as the Basilica of St. Sernin, Toulouse.

- Windows are increasingly of larger size and are often coupled, particularly in cloisters and towers.[9]

- The façade takes two forms, that with two large towers, such as that at Saint-Etienne, Caen, and the screen form with two small flanking turrets, as at Angouleme Cathedral.

- There are often three portals, as at the Abbey of la Trinité, Caen, left

- Façade decoration is rich and varied, with the central portal being the major feature.[9]

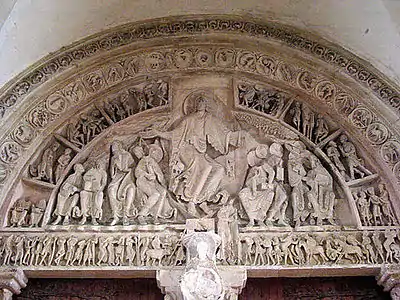

- Large sculptured portals are a distinguishing feature of French Romanesque. The portal is deeply recessed and the jambs set with shafts and mouldings. They typically have lintels, supporting a tympanum carved in high relief.[9]

- Interiors generally employed piers to support the arcades, rather than columns. The form of the piers became increasing complex with shafts and mouldings leading into the mouldings of the arch, or the vault as at Saint-Etienne Nevers. left[9]

- In the 12th century, cylindrical piers with Corinthian style capitals came into use.[9]

- A pattern of three stages—vault, arcade and clerestory—was established in the 11th century.[9]

- Masonry vaults were preferred for larger churches, and were initially barrel or groin vaults, often with arches spanning the nave between the vaults. Vaulted bays are square.[9]

- The earliest ribbed high vault in France is at Saint-Etienne, Caen (1120). The wide adoption of this method led to the development of Gothic architecture.[7][9]

- Several churches of Aquitaine and Anjou are roofed with domes, and have no aisles, as at Angouleme Cathedral.[9]

Notable examples

- Abbey Church of Cluny, Cluny, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté

- The Abbey of Saint-Etienne, Caen, Normandy

- The Church of the Abbey of la Trinité, Caen, Normandy

- The Basilica of St. Sernin, Toulouse, Occitania

- Angoulême Cathedral, Angoulême, Nouvelle-Aquitaine

- Saint-Front, Périgueux, Nouvelle-Aquitaine

- Notre Dame du Puy, Le Puy-en-Velay, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes

- Abbey Church of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, Nouvelle-Aquitaine

- Abbey of la Madaleine, Vézelay, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté

- Church of St Philibert, Tournus, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté

- Abbey of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, Occitania

- Abbey of Saint-Georges, Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville, Normandy

Romanesque churches in Britain and Ireland

St Mary the Virgin, Iffley, 12th century, shows the detailed carving, particularly chevrons, and the side portal typical of Britain.

St Mary the Virgin, Iffley, 12th century, shows the detailed carving, particularly chevrons, and the side portal typical of Britain. Southwell Minster 1108–1250, west front 1108–1150 (west window 1450). The severe twin-towered facade with balance of vertical buttresses and horizontal courses is similar to St Etienne, Caen. It has retained its simple spires.

Southwell Minster 1108–1250, west front 1108–1150 (west window 1450). The severe twin-towered facade with balance of vertical buttresses and horizontal courses is similar to St Etienne, Caen. It has retained its simple spires. Rochester Cathedral, 1115–1280, west front 1150 (west window 1470). The west front has its interior forms emphasised by the verticals of the large pinnacled buttresses. The portal is richly carved with Christ in Majesty.

Rochester Cathedral, 1115–1280, west front 1150 (west window 1470). The west front has its interior forms emphasised by the verticals of the large pinnacled buttresses. The portal is richly carved with Christ in Majesty.

Influences

- The Pre-Romanesque tradition of architecture was Saxon. The thick-walled churches without aisles had archway leading into rectangular chancels. Bell towers often had an attached circular stair turret. Windows were often arched or had triangular heads.[10]

- The Norman invasion of 1066 unified the government of England.[10]

- Norman bishops were installed in English cathedrals and monasteries were established following Benedictine, Cluniac, Cistercian, and Augustinian rules.[10][11]

- Monasteries were established in Wales, Scotland and Ireland, suppressing local Celtic monastic tradition.[12]

- Many cathedrals were of monastic foundation serving a dual role, which affected their architecture, in particular the extended length of the choir and transepts.[13]

- There was a great diversity of building stone including limestone, New Red Sandstone, flint and granite.[11]

- In England, the relative political stability led to large diocese with few bishops. Cathedrals were correspondingly few in number and large in scale.

- Geographical isolation led to the development of distinct regional character.[11]

- The climate led to the construction of long naves to facilitate processions in wet weather.[11]

- Of the medieval cathedrals, nearly all were commenced in this period, and several have remained substantially Norman structures.[14]

- Many parish churches were commenced at this period.[15]

- The abbey churches suffered destruction at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries in the early 16th century and the majority were reduced to ruins, some surviving as parish churches.[11]

The nave of Durham Cathedral has cylindrical piers with incised decoration, also found at Dunfermline Abbey, Scotland. Although Norman in character, the building has the first use of the pointed ribbed vault and flying buttresses.

The nave of Durham Cathedral has cylindrical piers with incised decoration, also found at Dunfermline Abbey, Scotland. Although Norman in character, the building has the first use of the pointed ribbed vault and flying buttresses. Peterborough Cathedral, the three-stage nave 1155–1175 has piers of ovoid section with attached shafts. While the forms are typically Norman, the length is greater than found in Normandy. The wooden ceiling is original.

Peterborough Cathedral, the three-stage nave 1155–1175 has piers of ovoid section with attached shafts. While the forms are typically Norman, the length is greater than found in Normandy. The wooden ceiling is original.

Kelso Abbey, Scotland, was founded by French monks and maintains French characteristics.

Kelso Abbey, Scotland, was founded by French monks and maintains French characteristics. Cormac's Chapel, Rock of Cashel, Ireland, with its steeply pitched roof and bands of blind arcading maintains a distinctly Irish character.

Cormac's Chapel, Rock of Cashel, Ireland, with its steeply pitched roof and bands of blind arcading maintains a distinctly Irish character.

Characteristics

- It is characteristic of the medieval churches of the British Isles and England in particular that they were continually expanded, altered and rebuilt.[16] Consequently, although Norman buildings are numerous, few are intact, and at some, such as Lincoln Cathedral, Gloucester Cathedral and Worcester Cathedral, Norman architecture might be represented only by the portals, the columns of the nave or the crypt.[17]

- The Norman facades of cathedrals and large abbeys follow the two basic forms found in France, that with paired towers as at Southwell Minster and that with framing turrets as at Rochester Cathedral.

- Portals are usually arched and decorated with chevrons and other geometric ornament, barbaric faces and spirals.[18] There are a few carved Romanesque tympanums, with a Christ in Majesty at Rochester Cathedral. The ornamentation of portals in Ireland have distinctive elements of Celtic design as at the gabled portal of Clonfert Cathedral.[12]

- Side porches are common and are often the usual mode of entrance, the western portal only being opened for major festivals.[11]

- Blind arcading is used as a major decorative feature, often around internal walls.[19]

- Windows are comparatively large and may be arranged in tiers as in the transepts of Peterborough Cathedral. Paired windows occur in towers.[18]

- Naves of cathedrals and abbey churches are of great length, and transepts are of strong projection.[13][14]

- Chancels of cathedrals and abbey churches are also very long.[13]

- The chancels of cathedrals and abbeys were round and with an ambulatory in the French manner, as indicated at Peterborough and Norwich Cathedrals but none have survived unchanged.[14]

- Large central towers are characteristic, as at Tewkesbury Abbey and Norwich Cathedral.

- Many round towers occur in Ireland. They are also found in Saxon (Pre-Romanesque) architecture in England as stair towers attached to larger towers of square plan.

- The nave rises in three stages, arcade, gallery and clerestory.[20]

- The arcade has two forms: arches resting on large cylindrical masonry columns as at Gloucester and Hereford Cathedrals, and arches springing from composite piers as at Peterborough and Ely Cathedrals. Durham Cathedral has alternating piers and columns.[21]

- Crypts are groin vaulted, as at Canterbury Cathedral.[22]

- Nearly every large Norman church has a later, Gothic high vault, except at Peterborough and Ely Cathedrals which have retained trussed wooden ceilings.[23] The vaults at Durham are of unique importance, that of the south aisle being the oldest ribbed vault in the world, and that of the nave being the earliest pointed ribbed vault in the world.[22] Ribbed vaults of the Norman period exist over the aisles at Peterborough Cathedral and other large churches.[22]

- Barrel vaults are rare, examples being St John's Chapel, Tower of London[22] and several 12th century monastic churches in Ireland including Cormac's Chapel and St Flannan's oratory.[12]

Notable examples

- Durham Cathedral, England

- Peterborough Cathedral, England

- Ely Cathedral, England

- Southwell Cathedral, England

- Rochester Cathedral, England

- Tewkesbury Abbey, England

- St Bartholomew-the-Great, London, England

- St Mary the Virgin, Iffley, England

- Kilpeck Church, England

- The Leper Chapel, Cambridge, England

- Dunfermline Abbey, Scotland

- Kelso Abbey, Scotland (ruined)

- Cormac's Chapel, Ireland

- St Mary Magdalene, Campsall, England

Romanesque churches in Spain, Portugal and Andorra

.jpg.webp) Church of Santa Coloma, Andorra, one of a group of such churches, built of rough stone, sometimes laid without mortar

Church of Santa Coloma, Andorra, one of a group of such churches, built of rough stone, sometimes laid without mortar Jaca Cathedral, Spain, has the deep side porch and galleried tower found on many Spanish churches.

Jaca Cathedral, Spain, has the deep side porch and galleried tower found on many Spanish churches. The imposing facade of Lisbon Cathedral, Portugal, The facade has two bell towers in the Norman manner and a wheel window.

The imposing facade of Lisbon Cathedral, Portugal, The facade has two bell towers in the Norman manner and a wheel window. The cupola of the Cathedral of Zamora has a ribbed stone vault and gives light to the centre of the church.

The cupola of the Cathedral of Zamora has a ribbed stone vault and gives light to the centre of the church. Old Cathedral of Coimbra, like in Lisbon it has a heavy, fortress-like quality.

Old Cathedral of Coimbra, like in Lisbon it has a heavy, fortress-like quality.

Influences

- Prior to the beginning of the period, the greater part of the Iberian Peninsula was ruled by Muslims, with Christian rulers controlling only a strip at the north of the country.[24][25]

- By 900 the Reconquista had increased the area under Christian rule to about one third of Iberia. This expanded to about half the area by 1150 and included Galicia, Leon, Castille, Navarre, Aragon, Catalonia and Portugal.[24]

- Romanesque churches are located in the northern half of the peninsula, with a number occurring in Avila which was re-established and fortified around 1100 and Toledo in central Spain from 1098.[25]

- Many small Pre-Romanesque churches were established in the 10th century with distinctive local characteristics including vaults, horseshoe arches, and rose windows of pierced stone.[25]

- Many Benedictine monasteries were established in Spain by Italian bishops and abbots, followed by the French orders of Cluniacs and Cistercians.

- In 1032, the church of Santa Maria de Ripoll was built to a complex plan with double aisles, inspired directly by Old St. Peter's Basilica. The church set a new standard for architecture in Spain.[26]

- Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela began as early as the 9th century, and by the 11th century was drawing pilgrims from England. The Way of Saint James (Camino de Santiago) was well established by the early 12th century and encouraged the foundation of monasteries along the route.[24]

- Most of the area has abundant building stone, granite, limestone, Red Sandstone and volcanic rubble.[24]

- There was little timber, so it was used sparingly for roofs.[24]

- The northern part of the region is dotted with numerous small churches such as those of Andorra and the Vall de Boí in Catalonia.[27][28] There are also larger monasteries. Many cathedrals were commenced at this time.[29]

The Church of San Lorenzo in Sahagún, Leon, has the tiered apses and galleried tower of brick churches in the region.

The Church of San Lorenzo in Sahagún, Leon, has the tiered apses and galleried tower of brick churches in the region. The west front of the Cathedral of Santa Maria d'Urgell has retained its

The west front of the Cathedral of Santa Maria d'Urgell has retained its Interior of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, a major pilgrimage destination.

Interior of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, a major pilgrimage destination. Sant Climent, Taüll, one of the Catalan Romanesque churches of the Vall de Boí

Sant Climent, Taüll, one of the Catalan Romanesque churches of the Vall de Boí

Characteristics

- It is characteristic of both cathedrals and large abbey churches that they have many accretions of different periods, particularly flanking chapels, in later styles, often Baroque.

- Most churches are built of stone. In areas where brick is used, Toledo, Sahagún, Cuéllar, the bricks are similar to Roman bricks. The exterior of brick churches, particularly the apses, are decorated with tiers of shallow blind arcading and square-topped niches, as at the churches of San Tirso and San Lorenzo, Sahagún

- Small churches abound across the area, usually having an aisleless nave and projecting apse and a bell turret on one gable.

- Larger churches often have a wide turret extending across the upper facade with a gallery of openings holding bells, as at Jaca Cathedral

- Larger monastic churches often have a short transept and three eastern apses, the larger off the nave and a smaller flanking apse off each transept as at La Seu Vella, Lleida.

- Lateral arcaded porches are a distinctive regional characteristic of small churches.[29] Larger churches sometimes have a similar narthex at the west as at Santa Maria, Ripoll

- Portals are typically deep set, round topped and with many mouldings, as at La Seu Vella, Lleida, Spain. Portals that are set within porches may be surrounded by rich figurative carvings as at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

- Freestanding towers with increasing openings in each stage, like those of Italy, occur with small churches.

- Small churches are sometimes barrel vaulted and are roofed with stone slabs lying directly on the vault.

- Wider spaces have timber roofs of low profile, as timber was scarce.

- Larger churches such as the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, have barrel vaults, sometimes with transverse arches marking the bays.

- Abbey churches of later French foundation have ribbed vaults.

- Larger monastic churches and cathedrals have nave and aisles and follow French plans, including chevets as at Avila Cathedral.

- The crossing of a large church sometimes has an octagonal tower or dome supported on squinches, as at Santa Maria, Ripoll and the Cathedral of Santa Maria d'Urgell .

- At the Old Cathedral, Salamanca and the Cathedral of Zamora there are polygonal crossing domes on pendentives, with narrow windows and with four small corner turrets.

- Externally, many large churches are fortresslike, such as Lisbon Cathedral and the Old Cathedral of Coimbra in Portugal and the Sigüenza Cathedral, Spain

- Rose windows with pierced tracery similar to those that occur in Pre-Romanesque churches of Oviedo are a feature in some facades, such as that at the Monastery of Santa María de Armenteira, Galicia.

Notable examples

- The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain

- Santa Maria de Ripoll, Ripoll, Catalonia, Spain

- The Cathedral of Santa Maria d'Urgell, La Seu d'Urgell, Catalonia, Spain

- Jaca Cathedral, Jaca, Aragon, Spain

- The cloister of the Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos, Santo Domingo de Silos, Castile and León, Spain

- San Martín de Tours, Frómista, Castile and León, Spain

- The Basilica of San Isidoro, León, Castile and León, Spain

- San Vicente, Ávila, Castile and León, Spain

- Sant Climent de Taüll, Taüll, Catalonia, Spain

- The Cathedral of Zamora, Zamora, Castile and León, Spain

- Old Cathedral, Salamanca, Castile and León, Spain

- Lisbon Cathedral, Portugal

- Old Cathedral of Coimbra, Portugal

- Monastery of Rates, Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal

Romanesque churches in Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands

Maastricht, Netherlands, showing the Basilica of Our Lady, Maastricht to the right, and the shorter towers of the Basilica of Saint Servatius (with the tower of St Jan's Church to the left)

Maastricht, Netherlands, showing the Basilica of Our Lady, Maastricht to the right, and the shorter towers of the Basilica of Saint Servatius (with the tower of St Jan's Church to the left) Sainte-Gertrude, Nivelles, Belgium, a sturdy church screened behind a large westwerk.

Sainte-Gertrude, Nivelles, Belgium, a sturdy church screened behind a large westwerk.

Influences

- Much of Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands were united under Charlemagne who built a castle on the Valkhof, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and the Palatine Chapel at Aachen.[30]

- The power of individual bishops and the establishment of cathedrals and monasteries were focused initially in the south of Germany and the Rhineland.[30]

- In the early 10th century Germany and Lombardy were united under Otto the Great, crowned in Charlemagne's church at Aachen.[30]

- Consolidation under Frederick Barbarossa in the 12th century led to the establishment of towns, imperial palaces and churches of imperial patronage.[30]

- Despite internal divisions and threats from Poland, Hungary and Denmark, Germany regained power and in the early 13th century Frederick II became Holy Roman Emperor of Germany, Sicily, Lombardy, Burgundy and Jerusalem.[30]

- Southern Germany, the Rhineland and Belgium had abundant building stone.[31]

- Saxony and Flanders had little stone, while large parts of the Netherlands and the river plains of northern Germany had none, so that brick was the main building material.[30][31]

- Timber was abundant in Germany and Belgium.[31]

- The rich fertile river valleys, particularly those of the Rhine and the Meuse, encouraged the growth of towns.[30]

- The period dating from the 9th to the 13th century produced Romanesque churches.[32] Several important Early Romanesque churches occur in Saxony at Hildesheim and Gernrode. Many of the most notable examples of Romanesque architecture occur around the Rhineland, with twelve churches of this period in the city of Cologne.

Worms Cathedral, Germany, is a double-apsed church with a side entrance.

Worms Cathedral, Germany, is a double-apsed church with a side entrance. Laach Abbey, Germany, has a westwerk that demonstrates the careful massing and balancing of forms that is typical of Romanesque architecture in Germany.

Laach Abbey, Germany, has a westwerk that demonstrates the careful massing and balancing of forms that is typical of Romanesque architecture in Germany.

Tournai Cathedral, Belgium, the south transept, is a balanced composition with much detail.

Tournai Cathedral, Belgium, the south transept, is a balanced composition with much detail._2010-12-19_025_adj.JPG.webp) Speyer Cathedral, Germany, an imperial church that set the style for the region, and includes a groin vault over the nave.

Speyer Cathedral, Germany, an imperial church that set the style for the region, and includes a groin vault over the nave.

Characteristics

- The most distinctive characteristic of large Romanesque churches is the prevalence of apses at both ends of the church, as on 9th-century Plan of St. Gall, the earliest example being at Gernrode Abbey. Two reasons are suggested: that the bishop presided at one end and the abbot at the other, or that the western apse served as a baptistery.[32]

- The main portal of a double-apsed church is into the side of the building, and may be richly decorated with carving.[32]

- Both apses are flanked by paired towers. Many of the smaller towers are circular, as at Worms Cathedral. There may be numerous towers of varied shapes and sizes.[33]

- The crossing is generally surmounted by an octagonal tower, as at Speyer Cathedral.

- Spires are of roofed timber rather than stone and take a variety of forms, the most distinctive being the Rhenish helm.[33] Stone is sometimes used for Rhenish helms as at the eastern end of the Basilica of Our Lady, Maastricht.

- The towers and apse of the western end are often incorporated into a multi-storey westwerk. These latter take a great variety of forms, from a flat façade as at Limburg Cathedral, a flat façade with projecting apse at St Gertrude, Nivelles and a rectangular projecting structure of several storeys that juts beyond the towers as at St Serviatius, Maastricht.

- The transepts do not project strongly.

- In the Rhineland, the exterior walls and towers are encircled with courses, Lombard bands and dwarf galleries, which serve to emphasise the individual mass of each component part of the whole, as at Speyer Cathedral.[33]

- Wheel windows, ocular windows and windows with simple quatrefoil tracery often occur in apses, as at Worms Cathedral.

- Wooden roofs were common, with an ancient painted ceiling retained at St Michael's, Hildesheim.

- Stone vaults were used at a later date than in France, occurring over the aisles at Speyer in about 1060.[32]

Notable examples

- Aachen Cathedral, Aachen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (Carolingian)

- Gernrode Abbey, Gernrode, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany

- St. Michael's Church, Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, Germany (Ottonian)

- Hildesheim Cathedral, Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, Germany

- Brunswick Cathedral, Braunschweig, Lower Saxony, Germany

- Speyer Cathedral, Speyer, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

- Worms Cathedral, Worms, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

- Mainz Cathedral, Mainz, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

- Naumburg Cathedral, Naumburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany

- Trier Cathedral, Trier, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

- Laach Abbey, Andernach, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

- Bamberg Cathedral, Bamberg, Bavaria, Germany

- Limburg Cathedral, Limburg, Hesse, Germany

- Collegiate Church of Saint Gertrude, Nivelles, Wallonia, Belgium

- Collegiate Church of St. Bartholomew, Liège, Wallonia, Belgium

- Tournai Cathedral, Tournai, Wallonia, Belgium

- Basilica of Our Lady, Maastricht, Limburg, the Netherlands

- Basilica of Saint Servatius, Maastricht, Limburg, the Netherlands

- Munsterkerk, Roermond, Limburg, the Netherlands

- Susteren Abbey, Susteren, Limburg, the Netherlands

Romanesque churches in Scandinavia

Old Aker Church, Norway, has a very large tower dividing the nave from the chancel.

Old Aker Church, Norway, has a very large tower dividing the nave from the chancel..jpg.webp) Nylars Church, Bornholm, Denmark, one of a group of rotunda church found in Denmark

Nylars Church, Bornholm, Denmark, one of a group of rotunda church found in Denmark At Aa Church, Bornholm, Denmark, the western tower has a fortified appearance and crow-step gables.

At Aa Church, Bornholm, Denmark, the western tower has a fortified appearance and crow-step gables. Lund Cathedral, Sweden, has an arcade with paired openings set under a single arch, in a manner common in gallery openings but not usual for nave arcades.

Lund Cathedral, Sweden, has an arcade with paired openings set under a single arch, in a manner common in gallery openings but not usual for nave arcades.

Influences

- Norway, Sweden and Denmark were separate kingdoms for much of the period.

- Much of Norway was united from the late 9th century until 1387 under Harold I and his successors.

- Cnut the Great briefly united Denmark, England, Norway and parts of Sweden in the early 11th century.

- King Olaf II of Norway, known as St Olav, did much to enforce Christianity on the Vikings, and by the end of the 11th century, Christianity was the only legal religion.

- In Denmark, Christianity was promoted by Canute the Holy in the late 11th century, with Sweyn II of Denmark dividing the country into eight dioceses, and establishing many churches, cathedrals and monasteries from about 1060 onwards.

- Much of Sweden was united under Olaf Eiríksson around 995, with the southern area, Götaland being united with Svealand by Sverker I of Sweden in the 1130s.

- Lund Cathedral, Sweden, was made the seat of the archbishop for all of Scandinavia in 1103, but only the crypt remains from the 1130s, the rest being mostly 19th century rebuilding.[34]

- Bishop Absalon founded Roskilde Cathedral in Denmark in 1158 and the city of Copenhagen (1160–67).

- Architectural influences came with clergy brought from England (such as Nicholas Breakspeare), Lombardy and Germany. The influence of English Norman architecture is seen particularly in Norway at Nidaros Cathedral, Trondheim, and of German Romanesque at Lund Cathedral, Sweden.[34]

- Benedictine monks from Italy introduced the skill of firing bricks to Denmark.

- While most churches were initially built of timber, the larger ones were replaced by stone, with brick being the dominant material in much of Denmark where building stone is scarce.

- Small Romanesque churches are plentiful and are generally in relatively unchanged condition. Large churches are rare and are much altered as at Aarhus Cathedral, Lund Cathedral and Roskilde Cathedral.[34]

- Norway has 25 wooden stave churches from this period,[34] making up all but three of the world's medieval wooden churches.

- In Sweden, surviving Romanesque churches are concentrated mainly but not exclusively to three provinces: Gotland, Scania and Västra Götaland

At Husaby Church, Sweden, the massive tower is framed by round turrets.

At Husaby Church, Sweden, the massive tower is framed by round turrets. Hopperstad Stave church, Norway (1130), one of twenty-five remaining from the Medieval period.

Hopperstad Stave church, Norway (1130), one of twenty-five remaining from the Medieval period.

Characteristics

- The wooden stave churches of Norway represent a type that was once common across Northern Europe, but elsewhere have been destroyed or replaced. They have timber frames, walls of planks, and shingled roofs which are steeply pitched and overhanging to protect the joints of the building from the weather.[34]

- Denmark has seven rotunda churches, which have a circular nave, divided into several storeys internally, and have projecting chancel and apse as at Bjernede Church and Nylars Church.[34] At Østerlars Church, the chancel and apse are constructed as small intersecting circles. Rotunda churches also occur in Sweden as at Hagby Church.

- Bulky west towers with stepped gables are typical of Denmark and are found on smaller churches as at Horne Church, Søborg Church, and Aa Church, Bornholm where the tower has paired crow-step gables at each side.

- In Denmark the west tower may extend across the whole width of the church, forming a westwerk as at Aa Church and Hvidbjerg Church, Morsø, with some such towers incorporating a large open archway with stairs such as at Torrild Church.

- Small stone churches in Norway and Sweden have a short wide nave, square chancel, an apse and a western tower with pyramidal shingled spire, as at Hove Church, Norway and Kinneveds Church and Våmbs Church, Sweden.

- Large central towers occur in Norway, as at Old Aker Church.

- Free standing belltowers are found, often with half-timbered upper sections.

- Stone churches, such as Aa Church, Denmark and Lund Cathedral, Sweden, have Lombard bands and paired windows, similar to churches of Lombardy and Germany.

- Openings are generally small and simple. Many doors have a carved tympanum as at Vestervig Church and Ribe Cathedral, Denmark

- Most churches have timber roofed naves, but ribbed vaulting over smaller spaces such as the chancel is common. Some small churches, such as Marka Church in Sweden, have groin vaults. Larger churches such as Ribe Cathedral are vaulted.

- Arcades may be of simple rectangular piers such as at Ribe, Denmark, or drum columns such as at Stavanger Cathedral, Norway. Lund Cathedral has alternating rectangular piers and piers with attached shafts which support the vault.

- Fully developed Romanesque arcades of three stages occur in churches built under English or German influence as at Nidaros Cathedral, Trondheim.[34]

- Large churches may have paired towers at the western end, as at Mariakirken, Bergen.

- Visby Cathedral and Husaby Church, Sweden, both have a tall westwerk, framed by round towers. At Ribe Cathedral the stone westwerk is framed on the south by a Romanesque tower of German form with a Rhenish helm spire and on the north by a taller Gothic tower in red brick.

Notable examples

- Hopperstad Stave Church, Vikøyri, Vestland, Norway (1130)

- Borgund Stave Church, Borgund, Vestland, Norway

- Aa Church, Aakirkeby, Bornholm, Denmark (late 12th century)

- Bjernede Church, Sorø, Zealand, Denmark

- Østerlars Church, Østerlars, Bornholm, Denmark

- Horne Church, Faaborg, Funen, Denmark

- Vestervig Church, Vestervig, Jutland, Denmark

- Roskilde Cathedral, Roskilde, Zealand, Denmark (1160–1280)

- St. Bendt's Church, Ringsted, Zealand, Denmark (1170)

- Ribe Cathedral, Ribe, Jutland, Denmark

- Old Aker Church, Oslo, Norway (1080)

- Stavanger Cathedral, Stavanger, Rogaland, Norway

- Buttle Church, Buttle, Gotland, Sweden

- Hemse Church, Hemse, Gotland, Sweden

- Fardhem Church, Fardhem, Gotland, Sweden

- Husaby Church, Husaby, Västergötland, Sweden

Romanesque churches in Poland, Austria, Hungary and the Czech Republic

Church of St Peter and St Paul, Budeč Czech Republic, one of several rotunda churches in the region.

Church of St Peter and St Paul, Budeč Czech Republic, one of several rotunda churches in the region. Tum Collegiate Church, Poland, restored after much damage, has small round towers flanking the eastern apses.

Tum Collegiate Church, Poland, restored after much damage, has small round towers flanking the eastern apses._7.jpg.webp) Ják Abbey, Hungary (1220-1256)

Ják Abbey, Hungary (1220-1256) Collegiate Church in Kruszwica, Poland

Collegiate Church in Kruszwica, Poland Lébény Abbey, Hungary, (early-13th century)

Lébény Abbey, Hungary, (early-13th century)

Influences

- The remaining buildings are few in number and the influences are diverse.[35]

- Poland became Christian under Mieszko I in 966, resulting in the foundation of the first Pre-Romanesque churches, including Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, Gniezno and Poznań Cathedrals.[35]

- During the period 976–1248 Austria was ruled by margraves of the House of Babenberg. Towns and monasteries were established.

- The Romanesque style was introduced to Poland from Germany with the founding of the bishopric of Gniezno in 1000.[35]

- In Hungary, Stephen I brought the Magyar states together in 1001 and created two Catholic archbishoprics.[35]

- Bohemia was largely Christianised in the 10th century under Vaclav I.[35]

- The bishopric of Prague was established in 973 with a Saxon Benedictine bishop, Thietmar.[35]

- The Benedictine, Premonstratensian and Augustinian orders founded monasteries and built abbey churches throughout the area.[35]

- The influence on architectural style was initially from Germany, and later from France and Italy.[35]

At St. Andrew's Church, Kraków, the plain westwerk resolves into octagonal towers.

At St. Andrew's Church, Kraków, the plain westwerk resolves into octagonal towers. Gurk Cathedral, Austria, has remarkably little adornment of the westwerk, and arbitrary placement of the lower windows

Gurk Cathedral, Austria, has remarkably little adornment of the westwerk, and arbitrary placement of the lower windows

Characteristics

- There are a number of surviving small rotunda churches, generally with an apse as at Öskü, Hungary and Saint Nicholas Rotunda in Cieszyn, Poland.[35]

- Rotunda churches sometimes have towers which may be circular as at Saint Procopius Church, Strzelno, Poland or square in plan as at the Church of St Peter and St Paul, Budeč, Czech Republic.

- Other small churches found in the region are rectangular, aisleless and with a square chancel,[35] or an apse as at the Church of Saint Wenceslaus, Hrusice, Czech Republic. Schöngrabern Church, Austria, has a square chancel and projecting apse.

- Larger churches have a nave and aisles, each ending in an apse, and with no transept.[35] Examples are Pécs Cathedral, Ják Church and the Basilica of the Assumption, Tismice, Czech Republic.

- The aisles sometimes contained galleries for the nobility.[35]

- While arcades are usually supported on piers, the Basilica of the Assumption, Tismice has alternating piers and columns which have cushion capitals.

- Larger churches have paired western towers, some with decorated central portals, as at Ják Church and the ruined Zsambek Church, Hungary.

- At St. Andrew's Church, Kraków, the unornamented facade takes the form of westwerk, with an octagonal towers rising on either side. Gurk Cathedral, Austria, has a similarly flat facade, rising to two very tall square towers.

- The Collegiate Church at Tum has and apse at either end, similar to many German Romanesque churches.[35] The western apse is flanked by square towers.

- Pécs Cathedral, Hungary, has four towers of square plan, like Bamberg Cathedral, Germany.

- Tower openings take the typical Romanesque paired form as at Church of St Peter and St Paul, Budeč, Czech Republic.

- Roofs are generally of wood, with vaults occurring.

- Lombard bands are used, as at Schöngrabern Church, Austria, and around the towers of Tum and Ják churches.

- The facade of Sulejów Abbey Church, founded by the Cistercians, and having a gabled portal and rose window, heralds the influence of French architectural style that was to introduce Gothic.

Notable examples

- Gurk Cathedral, Gurk, Carinthia, Austria

- Schöngrabern Church, Schöngrabern, Lower Austria, Austria

- Tum Collegiate Church, Tum, Poland

- St. Andrew's Church, Kraków, Lesser Poland, Poland

- St. Leonard's Crypt in Wawel Cathedral, Kraków, Lesser Poland, Poland

- Saint Procopius Rotunda Church, Strzelno, Kuyavia, Poland

- St Martin's Collegiate Church, Opatów, Lesser Poland, Poland

- Sulejów Abbey, Sulejów, Poland

- St. Nicholas Church, Wysocice, Lesser Poland, Poland

- St. Peter and Paul-Collegiate in Kruszwica, Kruszwica, Kuyavia, Poland

- Cathedral in Kamień Pomorski, Pomerania, Poland

- Dominican Church and Convent of St. James in Sandomierz, Sandomierz, Lesser Poland, Poland

- St. Trinity-Church in Strzelno, Kuyavia, Poland, with unique sculpted columns inside depicting vices and virtues.

- Zsámbék Church, Zsámbék, Hungary. The facade of this ruined Premonstratensian abbey church, (1220), has remained largely intact.

- Pécs Cathedral, Pécs, Hungary. Although the plan reflects the church of the 11th century, the exterior appearance is almost entirely due to 19th-century renovation.[36]

- Ják Church, Ják, Hungary, is one of the most complete Romanesque churches in the region.

- Church of Saint Wenceslaus, Hrusice, Bohemia, Czech Republic

- Church of St Peter and St Paul, Budeč, Bohemia, Czech Republic (c. 900 AD)

- Basilica of the Assumption, Tismice, Bohemia, Czech Republic

See also

- Romanesque architecture

- Romanesque secular and domestic architecture

- List of Romanesque architecture

- Romanesque art

- Romanesque sculpture

- Spanish Romanesque

- Renaissance of the 12th century

- Romanesque Revival architecture

- Medieval architecture

- Mosan art

- Pre-Romanesque art

- Ottonian architecture

- Gothic architecture

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- Architecture of cathedrals and great churches

References

- Notes

- Fletcher 1996

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter VII, pp. 303–308

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter VII, pp. 308–310

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter VIII, pp. 311–319

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter VIII, pp. 320–328

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter VIII, pp. 329–333

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter IX, pp. 340–347

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter IX, pp. 335–340

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter IX, pp. 347–352

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, pp. 386–397

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, pp. 379–386

- O'Keeffe 2003

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 402

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 490

- Cox & Ford 1961, pp. 47–48

- Clifton-Taylor 1986, p. 15

- Clifton-Taylor 1986, pp. 29–65

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 496

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 506

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 493

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 505

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 397

- Fletcher 1996, Chapter XII, p. 501

- Banister Fletcher, pp. 635–639

- Toman, Romanesque, Bruno Klein, Romanesque architecture in Spain and Portugal, pp. 178–179

- Bruno Klein, pp. 180–181

- The Romanesque, Andorra, the official site, (accessed 13 Aug 2012)

- Catalan Romanesque Churches of the Vall de Boí, UNESCO World Heritage List

- Romanesque in Castile-León, Spain thenandnow, (accessed 13 Aug 2012)

- Banister Fletcher, pp 353–357

- Banister Fletcher p. 570

- Banister Fletcher, p. 357

- Banister Fletcher, pp. 363–364

- Wischermann 1997a

- Wischermann 1997b

- World Monuments Fund: Pécs Cathedral

- Bibliography

- Wischermann, Heinfried (1997a). "The Romanesque Period in Scandinavia". In Toman, Rolf (ed.). Romanesque : architecture, sculpture, painting. Köln: Könemann. pp. 252–253. ISBN 3-89508-447-6.

- Wischermann, Heinfried (1997b). "The Romanesque Period in Scandinavia". In Toman, Rolf (ed.). Romanesque : architecture, sculpture, painting. Köln: Könemann. pp. 254–255. ISBN 3-89508-447-6.

- Fletcher, Banister (1996). Cruickshank, Dan (ed.). Sir Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture on the Comparative method (20 ed.). London: Architectural Press. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9.

- Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1986) [1967]. The cathedrals of England. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500200629.

- O'Keeffe, Tadhg (2003). Romanesque Ireland : architecture and ideology in the twelfth century. Dublin: Four Courts. ISBN 1851826173.

- Cox, John Charles; Ford, Charles Bradley (1961). Parish Churches. London: Batsford. OCLC 1114706. (1914 edition is available from Archive.org)

Further reading

- Gardner, Helen (2005). Kleiner, Fred S.; Mamiya, Christin J. (eds.). Gardner's Art through the Ages. Thomson/Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-15-505090-7.

- Holmes, George, ed. (1988). The Oxford illustrated history of medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820073-0.

- Huyghe, René (1958). Larousse Encyclopedia of Byzantine and Medieval Art. Paul Hamlyn.

- Icher, François (1998). Building the great cathedrals. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-4017-5.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (2009) [1957]. An Outline of European Architecture. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 978-1-4236-0493-8.

- Beckwith, John (1985) [1969]. Early medieval art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500200193.

- Kidson, Peter (1967). The Medieval World. London: Paul Hamlyn. OCLC 260121688.

- Bumpus, Thomas Francis (1928). The Cathedrals and Churches of Belgium (2 ed.). T. Werner Laurie. (1st edition available from Archive.org)

- Harvey, John Hooper (1961). English cathedrals. London: Batsford. OCLC 222355466.

External links

- Romanesque churches in Cologne,Germany

- Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland

- Overview of French Romanesque art

- French Romanesque art through 150 places (fr)(es)(en)

- Corrèze region Illustrated history (French)

- Italian, French and Spanish Romanesque art (it) (fr) (es) (en)

- Spanish and Zamora´s Romanesque art, easy navigation{es}

- Spanish Romanesque art{es}

- El Portal del Arte Románico Visigothic, Mozarabe and Romanesque art in Spain.

- Romanesque Churches in Portugal {en}

- The Nine Romanesque Churches of the Vall de Boi – Pyrenees – France {en}

- Satan in the Groin – exhibitionist carvings on mediæval churches