Recognition memory

Recognition memory, a subcategory of explicit memory, is the ability to recognize previously encountered events, objects, or people.[1] When the previously experienced event is reexperienced, this environmental content is matched to stored memory representations, eliciting matching signals.[2] As first established by psychology experiments in the 1970s, recognition memory for pictures is quite remarkable: humans can remember thousands of images at high accuracy after seeing each only once and only for a few seconds.[3]

Recognition memory can be subdivided into two component processes: recollection and familiarity, sometimes referred to as "remembering" and "knowing", respectively.[1] Recollection is the retrieval of details associated with the previously experienced event. In contrast, familiarity is the feeling that the event was previously experienced, without recollection. Thus, the fundamental distinction between the two processes is that recollection is a slow, controlled search process, whereas familiarity is a fast, automatic process.[4][5]

Mandler's "Butcher-on-the-bus" example:[4]

Imagine taking a seat on a crowded bus. You look to your left and notice a man. Immediately, you are overcome with this sense that you've seen this man before, but you cannot remember who he is. This automatically elicited feeling is familiarity. While trying to remember who this man is, you begin retrieving specific details about your previous encounter. For example, you might remember that this man handed you a fine chop of meat in the grocery store. Or perhaps you remember him wearing an apron. This search process is recollection.

Historical overview

The phenomenon of familiarity and recognition has long been described in books and poems. Within the field of Psychology, recognition memory was first alluded to by Wilhelm Wundt in his concept of know-againness or assimilation of a former memory image to a new one. The first formal attempt to describe recognition was by the English Doctor Arthur Wigan in his book Duality of the Mind. Here he describes the feelings of familiarity we experience as being due to the brain being a double organ.[6] In essence we perceive things with one half of our brain and if they somehow get lost in translation to the other side of the brain this causes the feeling of recognition when we again see said object, person etc. However, he incorrectly assumed that these feelings occur only when the mind is exhausted (from hunger, lack of sleep etc.). His description, though elementary compared to current knowledge, set the groundwork and sparked interest in this topic for subsequent researchers. Arthur Allin (1896) was the first person to publish an article attempting to explicitly define and differentiate between subjective and objective definitions of the experience of recognition although his findings are based mostly on introspections. Allin corrects Wigan's notion of the exhausted mind by asserting that this half-dream state is not the process of recognition.[6] He rather briefly refers to the physiological correlates of this mechanism as having to do with the cortex but does not go into detail as to where these substrates are located.[6] His objective explanation of the lack of recognition is when a person observes an object for a second time and experiences the feeling of familiarity that they experienced this object at a previous time.[6] Woodsworth (1913) and Margaret and Edward Strong (1916) were the first people to experimentally use and record findings employing the delayed matching to sample task to analyze recognition memory.[7] Following this Benton Underwood was the first person to analyze the concept of recognition errors in relation to words in 1969. He deciphered that these recognition errors occur when words have similar attributes.[8] Next came attempts to determine the upper limits of recognition memory, a task that Standing (1973) endeavored. He determined that the capacity for pictures is almost limitless.[9] In 1980 George Mandler introduced the recollection-familiarity distinction, more formally known as the dual process theory[4]

Dual-process versus single-process theories

It is debatable whether familiarity and recollection should be considered as separate categories of recognition memory. This familiarity-recollection distinction is what is called a dual-process model/theory. "Despite the popularity and influence of dual-process theories [for recognition memory], they are controversial because of the difficulty in obtaining separate empirical estimates of recollection and familiarity and the greater parsimony associated with single-process theories."[10] A common criticism of dual process models of recognition is that recollection is simply a stronger (i.e. more detailed or vivid) version of familiarity. Thus, rather than consisting of two separate categories, single-process models regard recognition memory as a continuum ranging from weak memories to strong memories.[1] An account of the history of dual process models since the late 1960s also includes techniques for the measurement of the two processes.[11]

Evidence for the single-process view comes from an electrode recording study done on epileptic patients who took an item-recognition task.[12] This study found that hippocampal neurons, regardless of successful recollection, responded to the familiarity of objects. Thus, the hippocampus may not exclusively subserve the recollection process. However, they also found that successful item recognition was not related to whether or not 'familiarity' neurons fired. Therefore, it's not entirely clear which responses relate to successful item recognition. However, one study suggested that hippocampal activation does not necessarily mean that conscious recollection will occur.[13] In this object-scene associative recognition study, hippocampal activation was not related to successful associative recollection; it was only when the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus was activated that successful performance was observed. Further, eye tracking evidence revealed that participants looked longer at the correct stimulus, and this was related to increases in hippocampal activity. Therefore, the hippocampus may play a role in the recovery of relational information, but it requires concomitant activation with the prefrontal cortex for conscious recollection.

Studies with amnesics, do not seem to support the single-process notion. A number of reports feature patients with selective damage to the hippocampus who are impaired only in recollection but not in familiarity, which provides tentative support for dual-process models.[14] Further, a double dissociation between recollection and familiarity has been observed.[15] Patient N.B. had regions of her medial temporal lobes removed, including the perirhinal cortex and entorhinal cortex, but her hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex were spared. She exhibited impaired familiarity but intact recollection processes relative to controls in a yes-no recognition paradigm, and this was elucidated using ROC, RK, and response-deadline procedures. In another study, even when performance between patient N.B. was matched to one amnesic patient who had their hippocampus removed, the double dissociation was still present.[16] While performance was matched post hoc and replication is needed, this evidence rules out the idea that these brain regions are part of a unitary memory strength system.[17] Instead, this double dissociation strongly suggests that distinct brain regions and systems underlie both recollection and familiarity processes.

The dual process theories make it possible to distinguish two types of recognition: first, recognizing THAT one has encountered some object/event before; and second recognizing WHAT that object/event was. Thus one may recognize a face, but only later recollect whose face it was.[11] Delayed recognition also shows differences between fast familiarity and slow recollection processes[18][19] In addition, in the “familiarity” system of recognizing memory two functional subsystems are distinguished: the first one is responsible for recognition of previously presented stimuli and the second one supports recognition of objects as new.[20]

At present, neuroscientific research has not provided a definitive answer to this controversy, although it heavily favors dual-process models. While many studies provide evidence that recollection and familiarity are represented in separate regions of the brain, other studies show that this is not always the case; there may be a great deal of neuroanatomical overlap between the two processes.[1] Despite the fact that familiarity and recollection sometimes activate the same brain regions, they are typically quite distinct functionally.[1]

The question of whether recollection and familiarity exist as two independent categories or along a continuum may ultimately be irrelevant; the bottom line is that the recollection-familiarity distinction has been extremely useful in understanding how recognition memory works.

Measurement and methods

Old-new recognition

Used to assess recognition memory based on the pattern of yes-no responses.[21] This is one of the simplest forms of testing for recognition, and is done so by giving a participant an item and having them indicate 'yes' if it is old or 'no' if it is a new item. This method of recognition testing makes the retrieval process easy to record and analyze.[22]

Forced choice recognition

Participants are asked to identify which of several items (two to four) is correct.[21] One of the presented items is the target—a previously presented item. The other items are similar, and act as distractors. This allows the experimenter a degree of manipulation and control in item similarity or item resemblance. This helps provide a better understanding of retrieval, and what kinds of existing knowledge people use to decide based on memory.[21]

Use of mental chronometry

When response time is recorded (in milliseconds or seconds), a faster speed is thought to reflect a simpler process, whereas slower times reflect more complex physiological processes.[21]

Hermann von Helmholtz was the first psychologist to inquire whether the velocity of a nerve impulse could be a speed that is measurable.[23] He devised an experimental set-up for measuring psychological processes with a very precise and critical time-scale. The birth of mental chronometry is attributed to an experiment by Helmholtz's colleague, Franciscus Donders. In the experiment, he attached electrodes to both feet of the subject. He then administered a mild shock to either the left or right foot, and told the subject to move the hand on the same side—which turned the stimulus (the shock) off. In a different condition, the subject was not told which foot the stimulus would act on. The time difference between these conditions was measured as one-fifteenth of a second. This was a significant finding in early experimental psychology, because researchers previously thought that psychological processes were too fast to measure.[23]

Dual process models

An early model of dual process theories was suggested by Atkinson and Juola's (1973) model.[24] In this theory, the familiarity process would be the first activated as a fast search for recognition. If that is unsuccessful in retrieving the memory trace, then there is a more forced search into the long-term memory store.[24]

The "horse-race" model is a more recent view of dual process theories. This view suggests that the two processes of familiarity and recollection occur simultaneously, but that familiarity, being the faster process, completes the search before recollection.[4] This view holds true the idea that familiarity is an unconscious process whereas recollection is more conscious, thoughtful.

Factors in recognition accuracy

Decision-making

In circumstances of uncertainty, identification of a prior occurrence depends on decision-making processes. The available information must be compared with some internal criteria that provide guidance on which decision is more advantageous.[25]

Signal detection theory has been applied to recognition memory as a method of estimating the effect of the application of these internal criteria, referred to as bias. Critical to the dual process model is the assumption that recognition memory reflects a signal detection process in which old and new items each have a distinct distribution along a dimension, such as familiarity.[26] The application of Signal Detection Theory (SDT) to memory depends on conceiving of a memory trace as a signal that the subject must detect in order to perform in a retention task. Given this conception of memory performance, it is reasonable to assume that percentage correct scores may be biased indicators of retention—just as thresholds may be biased indicators of sensory performance—and, in addition, that SDT techniques should be used where possible to separate the truly retention-based aspects of memory performance from the decision aspects.[27] In particular, we assume that the subject compares the trace strength of the test item with a criterion, responding "yes" if the strength exceeds the criterion and "no"otherwise. There are two types of test items, "old" (a test item that appeared in the list for that trial) and new" (one that did not appear in the list). Strength theory assumes that there may be noise in the value of the trace strength, the location of the criterion, or both. We assume that this noise is normally distributed.[28] The reporting criterion can shift along the continuum in the direction of more false hits, or more misses. The momentary memory strength of a test item is compared with the decision criteria and if the strength of the item falls within the judgment category, Jt, defined by the placement of the criteria, S makes judgment. The strength of an item is assumed to decline monotonically (with some error variance) as a continuous function of time or number of intervening items.[29] False hits are 'new' words incorrectly recognized as old, and a greater proportion of these represents a liberal bias.[25] Misses are 'old' words mistakenly not recognized as old, and a greater proportion of these represents a conservative bias.[25] The relative distributions of false hits and misses can be used to interpret recognition task performance and correct for guessing.[30] Only target items can generate an above-threshold recognition response because only they appeared on the list. The lures, along with any targets that are forgotten, fall below threshold, which means that they generate no memory signal whatsoever. False alarms in this model reflect memory-free guesses that are made to some of the lures.[31]

Level of processing

The level of cognitive processing performed on a given stimuli has an effect on recognition memory performance, with more elaborate, associative processing resulting in better memory performance.[32] For example, recognition performance is improved through the use of semantic associations over feature associations.[33] However, this process is mediated by other features of the stimuli, for example, the relatedness of the items to one another. If the items are highly interrelated, lower-depth item-specific processing (such as rating the pleasantness of each item) helps to distinguish them from one another, and improves recognition memory performance over relational processing.[34] This unusual phenomenon is explained by the automatic tendency to perform relational processing on highly interrelated items. Recognition performance is improved by additional processing, even of a lower level of associativeness, but not by a task that duplicates the automated processing already performed on the list of items.[35]

Context

There are a variety of ways that context can influence memory. Encoding specificity describes how memory performance is enhanced if testing conditions match learning (encoding) conditions.[36] Certain aspects during the learning period, whether it be the environment, your current physical state, or even your mood, become encoded in the memory trace. Later during retrieval, any of these aspects can serve as cues to aid in recognition. For example, research by Godden and Baddeley[37] tested this concept on scuba divers. One group of divers learned lists of words on land, and another group learned underwater. Not surprisingly, test results were highest when the retrieval conditions matched the encoding conditions (those who learned the word lists on land performed best on land, and those who learned underwater performed best underwater). There have also been studies that show similar effects regarding an individual's physical state. This is known as state-dependent learning.[38] Another type of encoding specificity is mood congruent memory, where individuals are more likely to remember material if the emotional content of the material and the prevailing mood at recall matched.[39]

The presence of other individuals can also have an effect on recognition. Two opposing effects, collaborative inhibition and collaborative facilitation impact memory performance in groups. Specifically, collaborative facilitation refers to the increased performance on recognition tasks in groups. The opposite, collaborative inhibition, refers to a decreased memory performance on recall tasks in groups.[40] This is because in a recall task, a specific memory trace must be activated, and outside ideas could produce a kind of interference. Recognition, on the other hand does not utilize the same manner of retrieval plan as recall and is therefore not affected.[41]

Recognition errors

The two basic categories of recognition memory errors are false hits (or false alarms) and misses.[30] A false hit is the identification of an occurrence as old when it is in fact new. A miss is the failure to identify a previous occurrence as old.

Two specific types of false hits emerge when elicited through the use of a recognition lure. The first is a feature error, in which a part of an old stimulus is presented in combination with a new element.[42] For example, if the original list contained "blackbird, jailbait, buckwheat", a feature error may be elicited through the presentation of "buckshot" or "blackmail" at test, as each of these lures has an old and a new component.[43] The second type of error is a conjunction error, in which parts of multiple old stimuli are combined.[42] Using the same example, "jailbird" could elicit a conjunction error, as it is a conjunction of two old stimuli.[43] Both types of errors can be elicited through both auditory and visual modalities, suggesting that the processes that produce these errors are not modality-specific.[44]

A third false hit error can be induced through the use of the Deese–Roediger–McDermott[45] paradigm. If all items studied are highly related to one word that does not appear on the list, the subject is highly likely to recognize that word as old in the test.[46] An example of this would be a list containing the following words: nap, drowsy, bed, duvet, night, relax. The lure in this case is the word 'sleep'. It is highly likely that 'sleep' would be falsely recognized as appearing on that list due to the level of activation received from the list words. This phenomenon is so pervasive that the rate of false generated in this manner can even surpass the rate of correct responses[47]

Mirror effect

According to Robert L. Green (1996), the mirror effect occurs when stimuli that are easy to recognize as old when old are also easy to recognize as new when new in recognition. The mirror effect refers to the consistency of the recognition of the stimuli in memory. In other words, they are easier to remember when you have previously studied the stimuli i.e., old, and easier to reject when you have not seen them before, i.e. new. Murray Glanzer and John K. Adams first described the mirror effect in 1985. The mirror effect has been effective in tests of associative recognition, measures of latency responses, discriminations of order, and others (Glanzer & Adams, 1985).

Neural underpinnings

On the whole, research concerning the neural substrates of familiarity and recollection demonstrates that these processes typically involve different brain regions, thereby supporting a dual-process theory of recognition memory. However, due to the complexity and inherent interconnectivity of the neural networks of the brain, and given the close proximity of regions involved in familiarity to regions involved in recollection, it is difficult to pinpoint the structures that are specifically related to recollection or to familiarity. What is known at present is that most of a number of neuroanatomical regions involved in recognition memory are primarily associated with one subcomponent over the other.

Normal brains

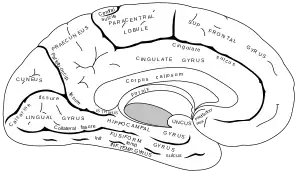

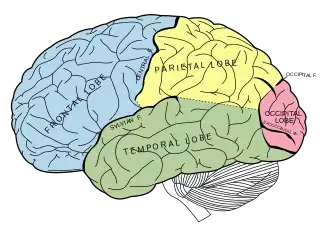

Recognition memory is critically dependent on a hierarchically organized network of brain areas including the visual ventral stream, medial temporal lobe structures, frontal lobe and parietal cortices[48] along with the hippocampus.[49] As mentioned previously, the processes of recollection and familiarity are represented differently in the brain. As such, each of the regions listed above can be further subdivided according to which part is primarily involved in recollection or in familiarity. In the temporal cortex, for instance, the medial region is related to recollection whereas the anterior region is related to familiarity. Similarly, in the parietal cortex, the lateral region is related to recollection whereas the superior region is related to familiarity.[49] An even more specific account divides the medial parietal region, relating the posterior cingulate to recollection and the precuneus to familiarity.[49] The hippocampus plays a prominent role in recollection whereas familiarity depends heavily on the surrounding medial-temporal regions, especially the perirhinal cortex.[50] Finally, it is not yet clear what specific regions of the prefrontal lobes are associated with recollection versus familiarity, although there is evidence that the left prefrontal cortex is correlated more strongly with recollection whereas the right prefrontal cortex is involved more in familiarity.[51][52] Though left-side activation involved in recollection was originally hypothesized to result from semantic processing of words (many of these earlier studies used written words for stimuli) subsequent studies using nonverbal stimuli produced the same finding—suggesting that prefrontal activation in the left hemisphere results from any kind of detailed remembering.[53]

As previously mentioned, recognition memory is not a stand-alone concept; rather it is a highly interconnected and integrated sub-system of memory. Perhaps misleadingly, the regions of the brain listed above correspond to an abstract and highly generalized understanding of recognition memory, in which the stimuli or items-to-be-recognized are not specified. In reality, however, the location of brain activation involved in recognition is highly dependent on the nature of the stimulus itself. Consider the conceptual differences in recognizing written words compared to recognizing human faces. These are two qualitatively different tasks and as such it is not surprising that they involve additional, distinct regions of the brain. Recognizing words, for example, involves the visual word form area, a region in the left fusiform gyrus, which is believed to specialized in recognizing written words.[54] Similarly, the fusiform face area, located in the right hemisphere, is linked specifically to the recognition of faces.[55]

Encoding

Strictly speaking, recognition is a process of memory retrieval. But how a memory is formed in the first place affects how it is retrieved. An interesting area of study related to recognition memory deals with how memories are initially learned or encoded in the brain. This encoding process is an important aspect of recognition memory because it determines not only whether or not a previously introduced item is recognized, but how that item is retrieved through memory. Depending on the strength of the memory, the item may either be 'remembered' (i.e. a recollection judgment) or simply 'known' (i.e. a familiarity judgment). Of course, the strength of the memory depends on many factors, including whether or not the person was giving their full attention to memorizing the information or whether they were distracted, whether they are actively attempting to learn (intentional learning) or only learning passively, whether they were allowed to rehearse the information or not, etc., although these contextual details are beyond the scope of this entry.

Several studies have shown that when an individual is devoting his/her full attention to the memorization process, the strength of the successful memory is related to the magnitude of bilateral activation in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus.[56][57][58] The greater the activation in these areas during learning, the better the memory. Thus, these areas are involved in the formation of detailed, recollective memories.[59] In contrast, when subjects are distracted during the memory-encoding process, only the right prefrontal cortex and left parahippocampal gyrus are activated.[52] These regions are associated with "a sense of knowing" or familiarity.[59] Given that the areas involved in familiarity are also involved in recollection, this conforms to a single-process theory of recognition, at least insofar as the encoding of memories is concerned.

In other senses

Recognition memory is not confined to the visual domain; we can recognize things in each of the five traditional sensory modalities (i.e. sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste). Although most neuroscientific research has focused on visual recognition, there have also been studies related to audition (hearing), olfaction (smell), gustation (taste), and tactition (touch).

Audition

Auditory recognition memory is primarily dependent on the medial temporal lobe as displayed by studies on lesioned patients and amnesics.[60] Moreover, studies conducted on monkeys[61] and dogs[62] have confirmed that perinhinal and entorhinal cortex lesions fail to affect auditory recognition memory as they do in vision. Further research needs must be done on the role of the hippocampus in auditory recognition memory, as studies in lesioned patients suggest that the hippocampus does play a small role in auditory recognition memory[60] while studies with lesioned dogs[62] directly conflict this finding. It has also been proposed that area TH is vital for auditory recognition memory[60] but further research must be done in this area as well. Studies comparing visual and auditory recognition memory conclude the auditory modality is inferior.[63]

Olfaction

Research on human olfaction is scant in comparison to other senses such as vision and hearing, and studies specifically devoted to olfactory recognition are even rarer. Thus, what little information there is on this subject is gleaned through animal studies. Rodents such as mice or rats are suitable subjects for odor recognition research given that smell is their primary sense.[64] "[For these species], recognition of individual body odors is analogous to human face recognition in that it provides information about identity."[65] In mice, individual body odors are represented at the major histocompatibility complex (MHC).[65] In a study performed with rats,[66] the orbitofrontal cortex (OF) was found to play an important role in odor recognition. The OF is reciprocally connected with the perirhinal and entorhinal areas of the medial temporal lobe,[66] which have also been implicated in recognition memory.

Gustation

Gustatory recognition memory, or the recognition of taste, is correlated with activity in the anterior temporal lobe (ATL).[67] In addition to brain imaging techniques, the role of the ATL in gustatory recognition is evidenced by the fact that lesions to this area result in an increased threshold for taste recognition for humans.[68] Cholinergic neurotransmission in the perirhinal cortex is essential for the acquisition of taste recognition memory and conditioned taste aversion in humans.[69]

Tactition

Monkeys with lesions in the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices also show impairment on tactual recognition.[70]

Lesioned brains

The concept of domain specificity is one that has helped researchers probe deeper into the neural substrates of recognition memory. Domain specificity is the notion that some areas of the brain are responsible almost exclusively for the processing of particular categories. For example, it is well documented that the fusiform gyrus (FFA) in the inferior temporal lobe is heavily involved in face recognition. A specific region in this gyrus is even named the fusiform face area due to its heightened neurological activity during face perception.[71] Similarly there is also a region of the brain known as the parahippocampal place area on the parahippocampal gyrus. As the name implies, this area is sensitive to environmental context, places.[72] Damage to these areas of the brain can lead to very specific deficits. For example, damage to the FFA often leads to prosopagnosia, an inability to recognize faces.[73] Lesions to various brain regions such as these serve as case study data that help researchers understand the neural correlates of recognition.

Medial temporal lobe

The medial temporal lobes and their surrounding structures are of immense importance to memory in general. The hippocampus is of particular interest. It has been well documented that damage here can result in severe retrograde or anterograde amnesia, the patient is unable to recollect certain events from their past or create new memories respectively.[74] However, the hippocampus does not seem to be the "storehouse" of memory. Rather, it may function more as a relay station. Research suggests that it is through the hippocampus that short term memory engages in the process of consolidation (the transfer to long term storage). The memories are transferred from the hippocampus to the broader lateral neocortex via the entorhinal cortex.[75] This helps explain why many amnesics have spared cognitive abilities. They may have a normal short term memory, but are unable to consolidate that memory and it is lost rapidly. Lesions in the medial temporal lobe often leave the subject with the capacity to learn new skills, also known as procedural memory. If experiencing anterograde amnesia, the subject cannot recall any of the learning trials, yet consistently improves with each trial.[76] This highlights the distinctiveness of recognition as a particular and separate type of memory, falling into the domain of declarative memory.

The hippocampus is also useful in the familiarity vs. recollection distinction in recognition as mentioned above. A familiar memory is a context free memory in which the person has a feeling of "know", as in, "I know I put my car keys here somewhere". It can sometimes be likened to a tip of the tongue feeling. Recollection on the other hand is a much more specific, deliberate, and conscious process, also termed remembering.[4] The hippocampus is believed heavily involved in recollection, whereas familiarity is attributed to the perirhinal cortex and broader temporal cortex in general, however, there is debate over the validity of these neural substrates and even the familiarity/recollection separation itself.[77]

Damage to the temporal lobes can also result in visual agnosia, a deficit in which patients are unable to properly recognize objects, either due to a perceptive deficit, or a deficit in semantic memory.[78] In the process of object recognition, visual information from the occipital lobes (such as lines, movement, colour etc.) must at some point be actively interpreted by the brain and attributed meaning. This is commonly referred to in terms of the ventral, or "what" pathway, which leads to the temporal lobes.[79] People with visual agnosia are often able to identify features of an object (it is small, cylindrical, has a handle etc.), but are unable to recognize the object as a whole (a tea cup).[80] This has been termed specifically as integrative agnosia.[78]

Parietal lobe

Recognition memory was long thought to involve only the structures of the medial temporal lobe. More recent neuroimaging research has begun to demonstrate that the parietal lobe plays an important, though often subtle[81] role in recognition memory as well. Early PET and fMRI studies demonstrated activation of the posterior parietal cortex during recognition tasks,[82] however, this was initially attributed to retrieval activation of precuneus, which was thought involved in reinstating visual content in memory.[83]

New evidence from studies of patients with right posterior parietal lobe damage indicates very specific recognition deficits.[84] This damage causes impaired performance on object recognition tasks with a variety of visual stimuli, including colours, familiar objects, and new shapes. This performance deficit is not a result of source monitoring errors, and accurate performance on recall tasks indicates that the information has been encoded. Damage to the posterior parietal lobe therefore does not cause global memory retrieval errors, only errors on recognition tasks.

Lateral parietal cortex damage (either dextral or sinistral) impairs performance on recognition memory tasks, but does not affect source memories.[85] What is remembered is more likely to be of the 'familiar', or 'know' type, rather than 'recollect' or 'remember',[81] indicating that damage to the parietal cortex impairs the conscious experience of memory.

There are several hypotheses that seek to explain the involvement of the posterior parietal lobe in recognition memory. The attention to memory model (AtoM) posits that the posterior parietal lobe could play the same role in memory as it does in attention: mediating top-down versus bottom-up processes.[81] Memory goals can either be deliberate (top-down) or in response to an external memory cue (bottom-up). The superior parietal lobe sustains top-down goals, those provided by explicit directions. The inferior parietal lobe can cause the superior parietal lobe to redirect attention to bottom-up driven memory in the presence of an environmental cue. This is the spontaneous, non-deliberate memory process involved in recognition. This hypothesis explains many findings related to episodic memory, but fails to explain the finding that diminishing the top-down memory cues given to patients with bilateral posterior parietal lobe damage had little effect on memory performance.[86]

A new hypothesis explains a greater range of parietal lobe lesion findings by proposing that the role of the parietal lobe is in the subjective experience of vividness and confidence in memories.[81] This hypothesis is supported by findings that lesions on the parietal lobe cause the perception that memories lack vividness, and give patients the feeling that their confidence in their memories is compromised.[87]

The output-buffer hypothesis of the parietal cortex postulates that parietal regions help hold the qualitative content of memories for retrieval, and make them accessible to decision-making processes.[81] Qualitative content in memories helps to distinguish those recollected, so impairment of this function reduces confidence in recognition judgments, as in parietal lobe lesion patients.

Several other hypotheses attempt to explain the role of the parietal lobe in recognition memory. The mnemonic-accumulator hypothesis postulates that the parietal lobe holds a memory strength signal, which is compared with internal criteria to make old/new recognition judgments.[81] This relates to signal-detection theory, and accounts for recollected items being perceived as 'older' than familiar items. The attention to internal representation hypothesis posits that parietal regions shift and maintain attention to memory representations.[81] This hypothesis relates to the AtoM model, and suggests that parietal regions are involved in deliberate, top-down intention to remember.

A possible mechanism of the parietal lobe's involvement in recognition memory may be differential activation for recollected versus familiar memories, and old versus new stimuli. This region of the brain shows greater activation during segments of recognition tasks containing primarily old stimuli, versus primarily new stimuli.[82] A dissociation between the dorsal and ventral parietal regions has been demonstrated, with the ventral region experiencing more activation for recollected items, and the dorsal region experiencing more activation for familiar items.[81]

Anatomy provides further clues to the role of the parietal lobe in recognition memory. The lateral parietal cortex shares connections with several regions of the medial temporal lobe, including its hippocampal, parahippocampal, and entorhinal regions.[81] These connections may facilitate the influence of the medial temporal lobe in cortical information processing.[82]

Frontal lobe

Evidence from amnesic patients have shown that lesions in the right frontal lobe are a direct cause of false recognition errors. Some suggest this is due to a variety of factors including defective monitoring, retrieval and decision processes.[88] Patients with frontal lobe lesions also showed evidence of marked anterograde and relatively mild retrograde face memory impairment.[89]

Evolutionary basis

The ability to recognize stimuli as old or new has significant evolutionary advantages for humans. Discerning between familiar and unfamiliar stimuli allows for rapid threat appraisals in often hostile environments. The speed and accuracy of an old/new recognition judgment are two components in a series of cognitive processes that allow humans to identify and respond to potential dangers in their environments.[90] Recognition of a prior occurrence is one adaptation that provides a cue of the utility of information to decision-making processes.[90]

The perirhinal cortex is notably involved in both the fear response and recognition memory.[91] Neurons in this region activate strongly in response to new stimuli, and activate less frequently as familiarity with the stimulus increases.[17] Information regarding stimulus identity arrives at the hippocampus via the perirhinal cortex,[92] with the perirhinal system contributing a rapid, automatic appraisal of the familiarity of the stimuli and the recency of its presentation.[93] This recognition response has the distinct evolutionary advantage of providing information for decision-making processes in an automated, expedient, and non-effortful manner, allowing for faster responses to threats.

Applications

A practical application of recognition memory is in relation to developing multiple choice tests in an academic setting. A good test does not tap recognition memory, it wants to discern how well a person encoded and can recall a concept. If people rely on recognition for use on a memory test (such as multiple choice) they may recognize one of the options but this does not necessarily mean it is the correct answer.[94]

References

- Medina, J. J. (2008). The biology of recognition memory Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. Psychiatric Times.

- (Norman & O'Reilly, 2003)

- Standing, L. (1973). "Learning 10,000 pictures". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 25(2), 207–222. Retrieved Jan 20 2020, from doi:10.1080/14640747308400340.

- Mandler, G. (1980). "Recognizing: The judgment of previous occurrence". Psychological Review. 87 (3): 252–271. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.87.3.252. S2CID 2166238.

- Jacoby, L. L. (1991). "A process dissociation framework: separating automatic from intentional uses of memory". Journal of Memory and Language. 30 (5): 513–541. doi:10.1016/0749-596X(91)90025-F.

- Allin, A. (1896). "Recognition". Psychological Review. 3 (5): 542–545. doi:10.1037/h0069343.

- Strong, M., & Strong E. (1916). "The Nature of Recognition Memory and of the Localization of Recognitions". The American Journal of Psychology. 27 (3): 341–362. doi:10.2307/1413103. JSTOR 1413103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dr. Dewey. "Recognition Errors" in Introduction to Psychology. intropsych.com

- Dr. Dewey. The Almost Limitless Capacity of Recognition Memory. in Introduction to Psychology. intropsych.com

- Curran, T.; Debuse, C.; Woroch, B.; Hirshman, E. (2006). "Combined Pharmacological and Electrophysiological Dissociation of Familiarity and Recollection". Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (7): 1979–1985. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5370-05.2006. PMC 6674941. PMID 16481430.

- Mandler, G. (2008). "Familiarity breeds attempts: A critical review of dual process theories of recognition". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 3 (5): 392–401. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00087.x. PMID 26158957. S2CID 205908239.

- Rutishauser, U.; Schuman, E. M.; Mamelak, A. N. (2008). "Activity of human hippocampal and amygdala neurons during retrieval of declarative memories". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (1): 329–334. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105..329R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706015105. PMC 2224211. PMID 18162554.

- Hannula, D. E.; Ranganath, C. (2009). "The Eyes Have It: Hippocampal Activity Predicts Expression of Memory in Eye Movements". Neuron. 63 (5): 592–599. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.025. PMC 2747814. PMID 19755103.

- Aggleton, J. P.; Brown, M. W. (1999). "Episodic memory, amnesia, and the hippocampal-anterior thalamic axis" (PDF). The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 22 (3): 425–444, discussion 444–89. doi:10.1017/S0140525X99002034. PMID 11301518. S2CID 11258997.

- Bowles, B.; Crupi, C.; Mirsattari, S. M.; Pigott, S. E.; Parrent, A. G.; Pruessner, J. C.; Yonelinas, A. P.; Kohler, S. (2007). "Impaired familiarity with preserved recollection after anterior temporal-lobe resection that spares the hippocampus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (41): 16382–16387. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10416382B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705273104. PMC 1995093. PMID 17905870.

- Bowles, B.; Crupi, C.; Pigott, S.; Parrent, A.; Wiebe, S.; Janzen, L.; Köhler, S. (2010). "Double dissociation of selective recollection and familiarity impairments following two different surgical treatments for temporal-lobe epilepsy". Neuropsychologia. 48 (9): 2640–2647. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.05.010. PMID 20466009. S2CID 25898729.

- Squire, L. R.; Wixted, J. T.; Clark, R. E. (2007). "Recognition memory and the medial temporal lobe: A new perspective". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 8 (11): 872–883. doi:10.1038/nrn2154. PMC 2323975. PMID 17948032.

- Mandler, G.; Boeck, W. J. (1974). "Retrieval processes in recognition". Memory & Cognition. 2 (4): 613–615. doi:10.3758/BF03198129. PMID 24203728.

- Rabinowitz, J.C.; Graesser, A.C.I. (1976). "Word recognition as a function of retrieval processes". Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 7: 75–77. doi:10.3758/bf03337127.

- Kozlovskiy, SA; Neklyudova, AK; Vartanov, AV; Kiselnikov, AA; Marakshina, JA (September 2016). "Two systems of recognition memory in human brain". Psychophysiology. 53: 93. doi:10.1111/psyp.12719.

- Radvansky, G. (2006) Human Memory. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Group, Inc.

- Finnigan, S.; Humphreys, MS; Dennis, S; Geffen, G (2002). "Erp". Neuropsychologia. 40 (13): 2288–2304. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00113-6. PMID 12417459. S2CID 5914792.

- Benschop, R.; Draaisma, D. (2000). "In Pursuit of Precision: The Calibration of Minds and Machines in Late Nineteenth-century Psychology". Annals of Science. 57 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/000337900296281. PMID 11624166. S2CID 37504910.

- Atkinson, R.C.; Juola, J.F. (1973). "Factors influencing speed and accuracy of word recognition". Attention and Performance. 6: 583–612.

- Bernbach, H. A. (1967). "Decision processes in memory". Psychological Review. 74 (6): 462–480. doi:10.1037/h0025132. PMID 4867888.

- Yonelinas, A. (2001). "Components of episodic memory: the contribution of recollection and familiarity", pp. 31–52 in A. Baddeley, J. Aggleton, & M. Conway (Eds.), Episodic memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Banks, William P. (1970). "Signal Detection Theory and Human Memory". Psychological Bulletin. 74 (2): 81–99. doi:10.1037/h0029531.

- Norman, Donald A.; Wayne A. Wckelgren (1969). "Strength Theory of Decision Rules and Latency in Retrieval from Short-Tem Memory" (PDF). Mathematical Psychology. 6 (2): 192–208. doi:10.1016/0022-2496(69)90002-9. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- Hinrichs, J. V. (1970). "A two-process memory-strength theory for judgment of recency". Psychological Review. 77 (3): 223–233. doi:10.1037/h0029101.

- Parks, T. E. (1966). "Signal-detectability theory of recognition-memory performance". Psychological Review. 73 (1): 44–58. doi:10.1037/h0022662. PMID 5324567.

- Wixted, John T. (2007). "Dual-Process theory and Signal Detection Theory of Recognition Memory". Psychological Review. 114 (1): 152–176. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.152. PMID 17227185. S2CID 1685052.

- Adams, J. (1967). Human memory. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Craik, F. I. M.; Lockhart, R. S. (1972). "Levels of processing: A framework for memory research". Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 11 (6): 671–684. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X. S2CID 14153362.

- Hunt, R. R.; Einstein, G. O. (1981). "Relational and item-specific information in memory". Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 20 (5): 497–514. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(81)90138-9.

- Roediger, H., & Guynn, M. (1996). "Retrieval Processes". pp. 197–236 in E. Bjork & R. Bjork (Eds.), Memory. California: Academic Press.

- Thomson, D. M.; Tulving, E. (1970). "Associative encoding and retrieval: Weak and strong cues". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 86 (2): 255–262. doi:10.1037/h0029997.

- Godden, D. R.; Baddeley, A. D. (1975). "Context-Dependent Memory in Two Natural Environments: On Land and Underwater". British Journal of Psychology. 66 (3): 325–331. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975.tb01468.x. S2CID 10699186.

- Goodwin, D. W.; Powell, B.; Bremer, D.; Hoine, H.; Stern, J. (1969). "Alcohol and Recall: State-Dependent Effects in Man". Science. 163 (3873): 1358–1360. Bibcode:1969Sci...163.1358G. doi:10.1126/science.163.3873.1358. PMID 5774177. S2CID 38794062.

- Bower, G. H. (1981). "Mood and memory". The American Psychologist. 36 (2): 129–148. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.129. PMID 7224324. S2CID 2215809.

- Weldon, M. S.; Bellinger, K. D. (1997). "Collective memory: Collaborative and individual processes in remembering". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 23 (5): 1160–1175. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.23.5.1160. PMID 9293627. S2CID 7373565.

- Hinsz, V. B. (1990). "Cognitive and consensus processes in group recognition memory performance". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 59 (4): 705–718. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.4.705.

- Jones, T. C.; Jacoby, L. L. (2001). "Feature and Conjunction Errors in Recognition Memory: Evidence for Dual-Process Theory". Journal of Memory and Language. 45: 82–102. doi:10.1006/jmla.2000.2761. S2CID 218476893.

- Jones, T. C.; Brown, A. S.; Atchley, P. (2007). "Feature and conjunction effects in recognition memory: Toward specifying familiarity for compound words". Memory & Cognition. 35 (5): 984–998. doi:10.3758/BF03193471. PMID 17910182. S2CID 19398704.

- Jones, T. C.; Jacoby, L. L.; Gellis, L. A. (2001). "Cross-Modal Feature and Conjunction Errors in Recognition Memory". Journal of Memory and Language. 44: 131–152. doi:10.1006/jmla.2001.2713. S2CID 53416282.

- Roediger, H. L.; McDermott, K. B. (1995). "Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 21 (4): 803–814. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.21.4.803.

- Nadel, L.; Payne, J. D. (2002). "The relationship between episodic memory and context: Clues from memory errors made while under stress". Physiological Research. 51 Suppl 1: S3–11. PMID 12479781.

- Roediger, H., McDermott, K., & Robinson, K. (1998). "The role of associative processes in creating false memories", pp. 187–245 in M. Conway, S. Gathercole, & C. Cornoldi (Eds.), Theories of memory II. Sussex: Psychological Press.

- Neufang, M.; Heinze, H. J.; Duzel, E. (2006). "Electromagnetic correlates of recognition memory processes". Clinical EEG and Neuroscience. 37 (4): 300–308. doi:10.1177/155005940603700407. PMID 17073168. S2CID 22137108.

- Yonelinas, A. P.; Otten, L. J.; Shaw, K. N.; Rugg, M. D. (2005). "Separating the Brain Regions Involved in Recollection and Familiarity in Recognition Memory". Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (11): 3002–3008. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5295-04.2005. PMC 6725129. PMID 15772360.

- Yonelinas, A. P. (2002). "The Nature of Recollection and Familiarity: A Review of 30 Years of Research". Journal of Memory and Language. 46 (3): 441–517. doi:10.1006/jmla.2002.2864. S2CID 145694875.

- Henson, R. N.; Rugg, M. D.; Shallice, T.; Josephs, O.; Dolan, R. J. (1999). "Recollection and familiarity in recognition memory: An event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study". The Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (10): 3962–3972. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03962.1999. PMC 6782715. PMID 10234026.

- Kensinger, E. A.; Clarke, R. J.; Corkin, S. (2003). "What neural correlates underlie successful encoding and retrieval? A functional magnetic resonance imaging study using a divided attention paradigm". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (6): 2407–2415. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02407.2003. PMC 6742028. PMID 12657700.

- Ranganath, C.; Johnson, M. K.; d'Esposito, M. (2000). "Left anterior prefrontal activation increases with demands to recall specific perceptual information". The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (22): RC108. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-j0005.2000. PMC 6773176. PMID 11069977.

- Cohen, L.; Dehaene, S. (2004). "Specialization within the ventral stream: The case for the visual word form area". NeuroImage. 22 (1): 466–476. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.049. PMID 15110040. S2CID 10459157.

- Kanwisher, N.; Wojciulik, E. (2000). "Visual attention: Insights from brain imaging". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 1 (2): 91–100. doi:10.1038/35039043. PMID 11252779. S2CID 20304513.

- Johnson, M. K.; Kounios, J.; Nolde, S. F. (1997). "Electrophysiological brain activity and memory source monitoring" (PDF). NeuroReport. 8 (5): 1317–1320. doi:10.1097/00001756-199703240-00051. PMID 9175136. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-14.

- Wagner, A. D.; Koutstaal, W.; Schacter, D. L. (1999). "When encodong yields remembering: Insights from event-related neuroimaging". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 354 (1387): 1307–1324. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0481. PMC 1692641. PMID 10466153.

- Brewer, J. B.; Zhao, Z.; Desmond, J. E.; Glover, G. H.; Gabrieli, J. D. (1998). "Making memories: Brain activity that predicts how well visual experience will be remembered". Science. 281 (5380): 1185–1187. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.1185B. doi:10.1126/science.281.5380.1185. PMID 9712581.

- Davachi, L.; Maril, A.; Wagner, A. D. (2001). "When Keeping in Mind Supports Later Bringing to Mind: Neural Markers of Phonological Rehearsal Predict Subsequent Remembering" (PDF). Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 13 (8): 1059–1070. doi:10.1162/089892901753294356. PMID 11784444. S2CID 6071005.

- Squire, L. R.; Schmolck, H.; Stark, S. M. (2001). "Impaired Auditory Recognition Memory in Amnesic Patients with Medial Temporal Lobe Lesions". Learning & Memory. 8 (5): 252–256. doi:10.1101/lm.42001. PMC 311381. PMID 11584071.

- Saunders, R.; Fritz, J.; Mishkin, M. (1998). "The Effects of Rhinal Cortical Lesions on Auditory Short-Term Memory in the Rhesus Monkey". Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 28: 757.

- Kowalska, D. M.; Kuśmierek, P.; Kosmal, A.; Mishkin, M. (2001). "Neither perirhinal/entorhinal nor hippocampal lesions impair short-term auditory recognition memory in dogs". Neuroscience. 104 (4): 965–978. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00140-3. PMID 11457584. S2CID 1916998.

- Cohen, M. A.; Horowitz, T. S.; Wolfe, J. M. (2009). "Auditory recognition memory is inferior to visual recognition memory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (14): 6008–6010. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.6008C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811884106. PMC 2667065. PMID 19307569.

- The Humane Society of the United States. (2007). Mouse Archived 2010-01-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- Schaefer, M. L.; Yamazaki, K.; Osada, K.; Restrepo, D.; Beauchamp, G. K. (2002). "Olfactory fingerprints for major histocompatibility complex-determined body odors II: Relationship among odor maps, genetics, odor composition, and behavior". The Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (21): 9513–9521. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09513.2002. PMC 6758037. PMID 12417675.

- Ramus, S. J.; Eichenbaum, H. (2000). "Neural correlates of olfactory recognition memory in the rat orbitofrontal cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (21): 8199–8208. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08199.2000. PMC 6772715. PMID 11050143.

- Small, D. M.; Jones-Gotman, M.; Zatorre, R. J.; Petrides, M.; Evans, A. C. (1997). "A role for the right anterior temporal lobe in taste quality recognition". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (13): 5136–5142. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05136.1997. PMC 6573307. PMID 9185551.

- Henkin, R. I.; Comiter, H.; Fedio, P.; O'Doherty, D. (1977). "Defects in taste and smell recognition following temporal lobectomy". Transactions of the American Neurological Association. 102: 146–150. PMID 616096.

- Gutierrez, R. (2004). "Perirhinal Cortex Muscarinic Receptor Blockade Impairs Taste Recognition Memory Formation". Learning & Memory. 11 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1101/lm.69704. PMC 321319. PMID 14747522.

- Suzuki, W. A.; Zola-Morgan, S.; Squire, L. R.; Amaral, D. G. (1993). "Lesions of the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices in the monkey produce long-lasting memory impairment in the visual and tactual modalities". The Journal of Neuroscience. 13 (6): 2430–2451. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02430.1993. PMC 6576496. PMID 8501516.

- Kanwisher, N. (2000). "Domain specificity in face perception". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (8): 759–763. doi:10.1038/77664. PMID 10903567. S2CID 1485649.

- Epstein, R.; Kanwisher, N. (1998). "A cortical representation of the local visual environment". Nature. 392 (6676): 598–601. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..598E. doi:10.1038/33402. PMID 9560155. S2CID 920141.

- De Renzi, E. (1986). "Prosopagnosia in two patients with CT scan evidence of damage confined to the right hemisphere". Neuropsychologia. 24 (3): 385–389. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(86)90023-0. PMID 3736820. S2CID 53181659.

- Zola-Morgan, S.; Squire, L. R. (1993). "Neuroanatomy of Memory" (PDF). Annual Review of Neuroscience. 16: 547–563. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.002555. PMID 8460903. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-27.

- Nestor, P. J.; Graham, K. S.; Bozeat, S.; Simons, J. S.; Hodges, J. R. (2002). "Memory consolidation and the hippocampus: Further evidence from studies of autobiographical memory in semantic dementia and frontal variant frontotemporal dementia". Neuropsychologia. 40 (6): 633–654. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00155-5. PMID 11792404. S2CID 3100970.

- Knowlton, B. J.; Squire, L. R.; Gluck, M. A. (2004). "Probabilistic category learning in amnesia" (PDF). Learning and Memory. 1: 106–120. doi:10.1101/lm.1.2.106. S2CID 439626.

- Ranganath, C.; Yonelinas, A. P.; Cohen, M. X.; Dy, C. J.; Tom, S. M.; d'Esposito, M. (2004). "Dissociable correlates of recollection and familiarity within the medial temporal lobes". Neuropsychologia. 42 (1): 2–13. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.07.006. PMID 14615072. S2CID 14415860.

- Humphreys, G. W., & Riddoch, M. J. (1987). To see but not to see: A case of visual agnosia. Hove, Uk: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ISBN 0863770657.

- Werner, J. & Chalupa, L (2004). The Visual Neurosciences. MIT Press. pp. 544–. ISBN 978-0-262-03308-4.

- Ellis, R., & Humphreys, G. (1999). Connectionist Psychology. Psychology Press. p. 548–549, ISBN 0863777872.

- Cabeza, R.; Ciaramelli, E.; Olson, I. R.; Moscovitch, M. (2008). "The parietal cortex and episodic memory: An attentional account". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 9 (8): 613–625. doi:10.1038/nrn2459. PMC 2692883. PMID 18641668.

- Wagner, A. D.; Shannon, B. J.; Kahn, I.; Buckner, R. L. (2005). "Parietal lobe contributions to episodic memory retrieval". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 9 (9): 445–453. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.07.001. PMID 16054861. S2CID 8394695.

- Fletcher, P. C.; Frith, C. D.; Baker, S. C.; Shallice, T.; Frackowiak, R. S. J.; Dolan, R. J. (1995). "The Mind's Eye—Precuneus Activation in Memory-Related Imagery". NeuroImage. 2 (3): 195–200. doi:10.1006/nimg.1995.1025. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-A200-7. PMID 9343602. S2CID 20334615.

- Berryhill, M. E.; Olson, I. R. (2008). "Is the posterior parietal lobe involved in working memory retrieval?". Neuropsychologia. 46 (7): 1775–1786. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.03.005. PMC 2494709. PMID 18439630.

- Davidson PS, Anaki D, Ciaramelli E, Cohn M, Kim AS, Murphy KJ, Troyer AK, Moscovitch M, Levine B (2008). "Does lateral parietal cortex support episodic memory?". Neuropsychologia. 46 (7): 1743–1755. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.011. PMC 2806230. PMID 18313699.

- Simons, J. S.; Peers, P. V.; Mazuz, Y. S.; Berryhill, M. E.; Olson, I. R. (2009). "Dissociation Between Memory Accuracy and Memory Confidence Following Bilateral Parietal Lesions". Cerebral Cortex. 20 (2): 479–485. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp116. PMC 2803741. PMID 19542474.

- Ally, B. A.; Simons, J. S.; McKeever, J. D.; Peers, P. V.; Budson, A. E. (2008). "Parietal contributions to recollection: Electrophysiological evidence from aging and patients with parietal lesions". Neuropsychologia. 46 (7): 1800–1812. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.026. PMC 2519009. PMID 18402990.

- Schacter, D. L.; Dodson, C. S. (2001). "Misattribution, false recognition and the sins of memory". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 356 (1413): 1385–1393. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0938. PMC 1088522. PMID 11571030.

- Rapcsak, S. Z.; Nielsen, L.; Littrell, L. D.; Glisky, E. L.; Kaszniak, A. W.; Laguna, J. F. (2001). "Face memory impairments in patients with frontal lobe damage". Neurology. 57 (7): 1168–1175. doi:10.1212/WNL.57.7.1168. PMID 11591831. S2CID 35086681.

- Klein, S. B.; Cosmides, L.; Tooby, J.; Chance, S. (2002). "Decisions and the evolution of memory: Multiple systems, multiple functions". Psychological Review. 109 (2): 306–329. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.109.2.306. PMID 11990320.

- Herzog, C.; Otto, T. (1997). "Odor-guided fear conditioning in rats: 2. Lesions of the anterior perirhinal cortex disrupt fear conditioned to the explicit conditioned stimulus but not to the training context". Behavioral Neuroscience. 111 (6): 1265–1272. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.111.6.1265. PMID 9438795.

- Manns, J. R.; Eichenbaum, H. (2006). "Evolution of declarative memory". Hippocampus. 16 (9): 795–808. doi:10.1002/hipo.20205. PMID 16881079. S2CID 39081299.

- Brown, M.; Aggleton, J. (2001). "Recognition memory: What are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus?". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2 (1): 51–61. doi:10.1038/35049064. PMID 11253359. S2CID 205012302.

- University of Waterloo. Writing Multiple Choice Tests Archived 2008-06-20 at the Wayback Machine.