Real Muthaphuckkin G's

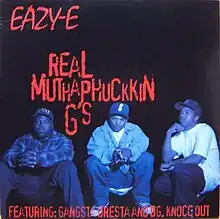

"Real Muthaphuckkin G's," or "Real Compton City G's" in its radio edit, is a diss track released as a single in August 1993 by American rapper Eazy-E with guest rappers Gangsta Dresta and B.G. Knocc Out. Peaking at #42 on Billboard's Hot 100, and the most successful of Eazy's singles as a solo artist,[4] it led an EP, also his most successful, It's On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa.[5] This diss track answers Eazy's former N.W.A bandmate Dr. Dre and his debuting, guest rapper Snoop Dogg, who had dissed Eazy on Dre's first solo album, The Chronic.

| "Real Muthaphuckkin G's" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Eazy-E featuring Dresta and B.G. Knocc Out | ||||

| from the album It's On ( | ||||

| Released | August 26, 1993 | |||

| Recorded | 1993 | |||

| Genre | G-funk,[1] gangsta rap[2] | |||

| Length | 5:32 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) | Dr.Dre | |||

| Eazy-E singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Real Muthaphuckkin G's" on YouTube | ||||

Dresta wrote his own verses and ghostwrote Eazy-E's verses, and B.G. Knocc Out wrote his own verse.[3] They performed the song live at 92.3 The Beat Summer Jam in 1994.

Backstory

In 1991, Dr. Dre left N.W.A and, with Suge Knight, launched Death Row Records. It released Dre's The Chronic, which in 1993 broke gangsta rap onto pop radio. On the album, Dre and guest rapper Snoop Doggy Dogg, a star on the rise at the time, diss Eazy-E in skits, in the single "Fuck wit Dre Day" plus its music video, and, closing the album, in the hidden track "Bitches Ain't Shit."[6][7]

To seize the moment, Eazy planned an EP, shorter than an album. Its lead single originally slated was "It's On."[8] But an Eazy associate got word of two halfbrothers, both Nutty Blocc Compton Crips, who rapped.[8] Recently released from several years of youth incarceration, Dresta had forged his rap skill through activities inside, whereby his reputation preceded him onto the streets.[8]

Visiting the brothers' house, Eazy's associate found Dresta and took him to the studio, where Eazy told him tales of Dre.[8] Dresta, thereby forming the song concept, wrote all the lyrics for an Eazy and Dresta duet.[8] Yet the next day, Dresta brought to the studio his brother Knocc Out, who, improvising it on the spot, added a verse.[8] And so Eazy's leading answer to Dre became "Real Muthaphuckkin G's."[6]

Content

The three "Real Muthaphukkin G's" rappers, claiming gangster authenticity, mock Dre and Snoop as "studio gangstas."[9] Also disputing Dre's masculinity, Eazy alludes to Dre's androgynous styling, by attire and makeup,[9] in the 1980s DJ crew World Class Wreckin' Cru, which, in line with Los Angeles county's hip hop scene until N.W.A, was also an electro rap group,[10] occasionally donning glitzy styling.[11] In the process, Eazy briefly disses Snoop as an "anorexic rapper" who weighs "60 pounds" when "wet and wearing boots."

Back to Dre, Eazy disparages the sentiment that beating a woman makes one a man, as Dre's assault of TV personality Dee Barnes was highly publicized.[12] Further, Eazy refers to the single "Fuck wit Dre Day" as "Eazy's pay day." Dre's contract with Eazy's label, Ruthless Records, left Eazy profiting from Dre's earnings through Death Row.[13] Finally, claiming rumors that Death Row is Dre's "boot camp," Eazy calls its CEO, Suge Knight, widely known for strongarm tactics in the music business, Dr. Dre's "sergeant."

Music video

The music video, written and directed by Eazy-E's longtime Ruthless video director Marty Thomas, was shot in Compton, California. It opens with aerial shots of Compton streets and scenes of lowriders, gangsters, and the metro Blue Line. There are numerous cameo appearances: Kokane, Rhythm D, Cold 187um, Dirty Red, Krazy Dee, Steffon, H.W.A., DJ Slip from Compton's Most Wanted, Young Hoggs, Blood of Abraham, K9 Compton, and Tony-A.

Once Eazy-E, on camera, raps, "All of a sudden, Dr. Dre is the G thang / But on his old album covers, he was a she-thang," shown is a photo of Dre on a World Class Wreckin' Cru album cover, predating N.W.A, wearing a white, sequined jumpsuit and detectable makeup.[9] Related cover photos appear several times during the video. On the other hand, nearly closing the video, in Eazy's hand, artificially blurred out, is perhaps a pistol while he alleges that if disobedient, Dre would get popped by Suge Knight's Smith & Wesson.

Previously, in Dr. Dre's music video for "Fuck wit Dre Day," actor and comedian Anthony "A. J." Johnson parodies Eazy-E as "Sleazy-E." In the "Real Muthaphuckkin G's" video, A. J. reprises the Sleazy-E role. As Eazy-E's music video opens, still jittering, Sleazy stands roadside, holding up the sign WILL RAP FOR FOOD. But Eazy's posse, including Dresta and Knocc Out, chase him through town, and finally pull him into van. As the video closes, Sleazy lies, apparently dead, at his original, roadside spot. The clean version's video closes instead with Sleazy, running again, falling flat at a Leaving Compton sign.

Although paid in advance, Johnson failed to appear for his second of two days shooting.[14] Eventually, he publicly confirmed the speculation that he had been threatened by Death Row or by its associates.[14] Johnson explained that Suge Knight had summoned him to his office and threatened him with a gun, eliciting A. J.'s agreement to abandon the video shoot.[14] Johnson informed Eazy of the threat, and recommended fellow comedian Arnez J to replace him in the video.[14]

Charts

| Chart (1993–94) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Hot 100[15] | 42 |

| US Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs (Billboard)[16] | 12 |

| US Hot Rap Songs (Billboard)[17] | 2 |

See also

References

- "The 30 best G-Funk tracks of all time". Fact Magazine. July 26, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- A. Berry, Peter (May 31, 2018). "Hip-Hop Fans Name the Most Disrespectful Diss Track of All Time". XXL. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

Returning to the peak of 1990s gangsta rap, more than a few folks called Eazy-E's epic Dr. Dre diss, "Real Muthaphuckkin G's," the most disrespectful ever.

- "Dresta on Writing Eazy-E's Lyrics for 'Real Compton City G's', AJ Johnson Situation (Part 5)". YouTube. November 8, 2018. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- Joel Whitburn, Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955–2002, 10th edn. (Record Research Inc., 2003), p 217.

- Gerrick D. Kennedy, Parental Discretion Is Advised: The Rise of N.W.A and the Dawn of Gangsta Rap (New York: Atria Books, 2017), p 211.

- Sacha Jenkins, Elliott Wilson, Gabe Alvarez, Jeff Mao & Brent Rollins, eds., Ego Trip's Book of Rap Lists (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2014), p 237.

- Thomas Golianopoulous, "Dr. Dre, 'The Chronic' at 20: Classic track-by-track review", Billboard.com, 15 Dec 2012.

- On the single's production, see Vlad Lyubovny, interviewer, "BG Knocc Out: Story behind Eazy-E's Dre diss 'Compton City G's' ", VladTV–DJVlad @ YouTube, 22 Sep 2015, or for deeper backstory, "Dresta & BG Knocc Out (full interview)", 13 Dec 2018. For a glimpse of the times, see Arsenio Hall, interviewer, with Eazy-E, guest, and live stage performance featuring Dresta and Knocc Out, The Arsenio Hall Show, Season 6, Episode 64, 10 Dec 1993.

- Elijah Lossner, "Studio gangsta", in Mickey Hess, ed., Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture, Volume 1 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007), p 325.

- David Diallo, ch 10 "From electro-rap to G-funk: A social history of rap music in Los Angeles and Compton, California", in Mickey Hess, ed., Hip Hop in America: A Regional Guide, Volume 1: East Coast and West Coast (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press, 2010), with pp 228–231 on the original gangsta rapper Ice-T, p 233 and following on the World Class Wreckin' Cru transitional period, and pp 234–238 on N.W.A, igniting the LA scene's switch from electro and funk rap to hardcore and gangsta rap.

- Retrospectively harped upon by others, too, Dre's androgynous styling on the album cover, circa 1985, was en vogue in LA's contemporary rap scene, dominated by electro-funk rap, but nonetheless was infrequent even for the World Class Wreckin' Cru, which usually performed in commonplace styling, jeans and sneakers [Marquette "Cli-ntel" Hawkins's letter, "Re: Kevin Powell's article 'Little Big Man' about Eazy-E, Dr. Dre, and the World Class Wreckin' Cru", Vibe, Mar 1994;2(2):20].

- Newsweek staff, "Number one with a bullet", Newsweek, 30 Jun 1991; Bethonie Butler, "Dr. Dre confronts his 1991 assault on Dee Barnes in HBO's 'The Defiant Ones' ", Washington Post, 11 Jul 2017.

- Death Row's distributor, Interscope Records, paid Ruthless a "huge" cash payout and publishing royalties on Dre's Death Row earnings: 10% on production and 15% on solo performance [Gerrick D. Kennedy, Parental Discretion Is Advised (New York: Atria Books, 2017), p 156]. By some estimates, Eazy netted up to some $1.5 million before his 1995 death: 25 to 50 cents per copy on some three million sold [Al Shipley, "Dr. Dre's The Chronic: 10 things you didn't know", Rolling Stone, 15 Dec 2017].

- Vlad Lyubovny, interviewer, "AJ Johnson: Suge pulled a gun on me for playing 'Sleazy-E' in Eazy-E's video (part 3)", VladTV–DJVlad @ YouTube, 1 Oct 2018.

- "Eazy-E Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- "Eazy-E Chart History (Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- "Eazy-E Chart History (Hot Rap Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved February 12, 2016.