Raynham Hall Museum

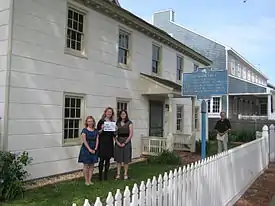

Raynham Hall is in Oyster Bay, New York. Home of the Townsend family, one of the founding families of Oyster Bay, on Long Island, New York, and a member of George Washington's Culper Ring of spies, the house was renamed Raynham Hall (seat of the Marquesses Townshend) after the Townsend seat in Norfolk, England, in 1850 by a grandson of the original owner. The house is now owned by the Town of Oyster Bay and operated as a public museum by the Friends of Raynham Hall Museum, Inc. Raynham Hall is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a Town of Oyster Bay Landmark, and is a featured site on the Oyster Bay History Walk audio walking tour. It is located at 20 West Main Street, in the heart of Oyster Bay. The new Visitors' Center, located next to the historic house at 30 West Main Street, is where guests can purchase tour tickets and see the museum shop.

Raynham Hall | |

"Townsend House" as it appeared around the time of the American Revolution | |

| |

| Location | 30 W Main St, Oyster Bay, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°52′20.21″N 73°31′53.83″W |

| Built | 1738 |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001264 |

| Added to NRHP | June 5, 1974[1] |

Description

Raynham Hall was built in 1738 as a "two by two," or two rooms on the first floor with two rooms above it, with a central chimney. After Samuel Townsend bought the house and moved in, he added onto the home four more rooms, giving the newly dubbed "Homestead" a lean-to addition in the saltbox-style structure.[2] The home remained this way until 1851, when Solomon Townsend remade the house in the Victorian style, adding carpeting, highly decorated wallpaper, ornate furnishings, a central tower onto the house's exterior with a skylight, as well as an entire new wing to the home. Renaming the house "Raynham Hall," Solomon projected his wealth and affluence where his colonial Quaker counterparts lived a much more conservative style. In 1941, the family no longer had the wealth to retain the house and handed the deed over to the Daughters of the American REVOLUTION'S (DAR) local chapter in Oyster Bay. The maintenance of the house by the DAR was too much, and finally the home was granted to the Town of Oyster Bay. After deliberation, it was decided that Raynham Hall would continue as a part of Oyster Bay as a historic home and museum to represent the Colonial and Victorian lifestyles of the Townsend family.

History

Before the Revolution

On May 6, 1738, Samuel Townsend (1717–1790) purchased the property now known as Raynham Hall from Thomas Weedon for 70 pounds.[3] At that time, the house consisted of four rooms with a large central chimney. It is possible that Weedon, whose trade is listed as a carpenter, may have constructed the original building.[3]

Between 1738 and 1740, Townsend enlarged the property to expand it to eight rooms, making it a story-and-a-half salt box.[4] Although the rooms may seem small to us today, the house was fairly large by 18th century standards. Townsend was a merchant, as well as Justice of the Peace and Town Clerk, and at least one of the front rooms of the house may have been used both as an office and a store.[5]

During the War

The Outbreak of the Revolution found Samuel Townsend's sympathies on the side of the Patriots despite the fact that half of Oyster Bay's inhabitants were Loyalists.[6] Townsend went on to become a member of the New York Provincial Congress, which voted to ratify the Declaration of Independence on July 9, 1776.[7]

Following the Patriots' defeat at the Battle of Long Island in the autumn of 1776, the Townsend home became the headquarters for the Loyalist Queen's Rangers, led by British Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe.[8] Since resisting a British officer could mean imprisonment or death, Samuel Townsend and his family had little choice but to make room for Col. Simcoe and his fellow officers. At this time, those members of the Townsend family living at Raynham Hall probably numbered seven, including five children (two boys - William and David, and three girls - Audrey, Sally, and Phebe) as well as Samuel and his wife Sarah Stoddard.[9] In addition, a census taken in 1781 shows that Samuel owned eight slaves, one man and three women and four children.[9] Samuel's older sons, Solomon, Samuel, and Robert were all engaged in trade and living away from home.[10] Whatever their personal feelings were regarding the British, the family seemed to get along quite well with the officers on a certain level. In fact, on Valentine's Day 1778, Lt. Col. Simcoe gave Sally a Valentine, and a number of compliments were etched on panes of glass from the soldiers to two of the sisters.[11] Even Robert Townsend who worked as a spy for General Washington during the Revolution, remarked when Major Andre died that he had "never felt more sensibly for the death of a person.[12]

Raynham Hall finds its place in national history through the activities of Robert Townsend. Prior to the outbreak of war, Robert had served as a purchasing agent for his father.[13] However by the late 1770s he was living and working in Manhattan as a merchant and a freelance journalist.[14] Since his business contacts brought him into close contact with many of the British officers then occupying the city, Abraham Woodhull, known within the New York spy ring as "Culper, Sr.," asked Robert if he would act as a spy in the city.[15] With a certain amount of reluctance Robert accepted the position[15] and became known as "Culper, Jr.," thus completing the circle of communication that went from Manhattan to Setauket across the sound to Connecticut and on the General George Washington's headquarters. From August 1779 until May of the following year, Robert provided George Washington with as much useful information as he could gather regarding British plans and troop movements. In May 1780, Culper, Jr. abruptly stopped work only to resume again in July. One of Robert's Oyster Bay cousins, Samuel Townsend (1744–1792) also served the colonial cause as a captain and Paymaster in the New York 5th Regiment of the Continental Line.[16][17][18]

The Valentine

In the winter of 1779, Lieutenant Colonel John Simcoe gave a Valentine's Day letter to Sarah 'Sally' Townsend, the daughter of Samuel Townsend and Sarah Stoddard Townsend. The museum claims that this letter is the first recorded Valentine's Day letter in America.

Fairest Maid, where all is fair

Beauty's pride and Nature's care;

To you my heart I must resign

O choose me for your Valentine!

Love, Mighty God! Thou know'st full well

Where all thy Mother's graces dwell,

Where they inhabit and combine

To fix thy power with spells divine;

Thou know'st what powerful magick lies

Within the round of Sarah's eyes,

Or darted thence like lightning fires

And Heaven's own joys around inspires;

Thou know'st my heart will always prove

The shrine of pure unchanging love!

Say; awful God! Since to thy throne

Two ways that lead are only known-

Here gay Variety presides,

And many a youthful circle guides

Through paths where lilies, roses sweet,

Bloom and decay beneath their feet;

Here constancy with sober mein

Regardless of the flowery Scene

With Myrtle crowned that never fades,

In silence seeks the Cypress Shades,

Or fixed near Contemplation's cell,

Chief with the Muses loves to dwell,

Leads those who inward feel and burn

And often clasp the abandon'd urn,--

Say, awful God! Did'st thou not prove

My heart was formed for Constant love?

Thou saw'st me once on every plain

To Delia pour the artless strain -

Thou wept'sd her death and bad'st me change

My happier days no more to range

O'er hill, o're dale, in sweet Employ,

Of singing Delia, Nature's joy;

Thou bad'st me change the pastoral scene

Forget my Crook; with haughty mien

To raise the iron Spear of War,

Victim of Grief and deep Despair:

Say, must I all my joys forego

And still maintain this outward show?

Say, shall this breast that's pained to fell

Be ever clad in horrid steel?

Now swell with other joys than those

Of conquest o'er unworthy foes?

Shall no fair maid with equal fire

Awake the flames of soft desire:

My bosom born, for transport, burn

And raise my thoughts from Delia's urn?

"Fond Youth," the God of Love replies,

"Your answer take from Sarah's eyes."

From the homestead to the hall: the Victorian Era

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Raynham Hall was occupied by various members of the Townsend Family. Phebe married Dr. Ebenezer Seely of Norwalk, Connecticut on December 25, 1808, when Phebe was 45 years of age Dr. Seely became the owner of the house in 1812 through a transfer from Sally Townsend. Robert and his sister, Sally, along with the Seelys, spent their adult lives at the "Old Homestead" (Raynham Hall). Robert died in 1838 at the age of 85 and Sally in 1842 at the age of 82. In 1851, Solomon Townsend, grandson of Samuel, purchased the Townsend home and land from Dr. Seely for $1,300 (~$45,729 in 2022). Solomon transformed the house by adding a rear wing, a water tower and a number of other Victorian architectural features. He then renamed the house Raynham Hall after the baronial great house, begun in 1619, of the famous Townshends in Norfolk, England. Despite some "wishful thinking," the families are not related to one another (Townsendsociety.org). It appears that Solomon had spent summers in Oyster Bay until 1861, when he moved there permanently from New York City at the outbreak of the Civil War. Like his father and grandfather before him, Solomon II was also a merchant and importer. By his early twenties he had begun his own business which would eventually be known as Townsend, Clinch and Dike. In 1849, at the age of 44, he married his first cousin Helene DeKay.[19] The couple had six children, five boys and a girl, all of whom were brought up in Raynham Hall. By 1860, he was one of the wealthiest men in Oyster Bay with a personal worth of $97,000 (~$2.44 million in 2021).

In keeping with the tradition of public service established by his father and grandfather, Solomon II represented New York Count in the State Legislature and served as a delegate to two State Constitutional Conventions. He also completed two terms as Commissionaire of Education in New York City and after his return to Oyster Bay served as president to the Oyster Bay Board of Education.

Raynham Hall becomes a museum

Solomon died on April 2, 1880. His wife, Helene, died on February 3, 1895, leaving daughter Maria holding the land and house. In one of her obituaries, Helene Townsend was described as "preeminently domestic in her habits,"[20] a phrase which helps conjure up the busy Victorian household which must have existed at Raynham Hall. Maria died on March 7, 1908, without a will. Her brothers Maurice and Solomon Samuel were left residing at the house. As a result of family dispute, the courts ordered that the house and various lots be sold to pay Maria's debts. Edward Nicholl Townsend Jr. (grandson of Solomon II) purchased the house for $4,800 (~$98,471 in 2021) on October 14, 1912. The last Townsend to live in Raynham Hall was Maurice, who died at the Amityville Sanitarium on November 26, 1927. In 1914 Julia Weeks Cole (niece of Helene DeKay), with the help of her sister Sallie Townsend Coles Halstead, purchased Raynham Hall for $100 (~$2,922 in 2022) to preserve it from change. During their tenure, it was used as both a tea room and meeting place for the Oyster Bay Historical and Genealogical Society. In 1933 Miss Coles deeded the house to the Oyster Bay Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), with a mortgage of $20,000 (~$338,684 in 2021). The DAR maintained the house through the depression, and in 1941 Miss Cole gave the house to DAR. The DAR continued to keep the house open to the public, as well as maintaining the Raynham Hall Tea Room. Six years later, maintenance on Raynham Hall became too burdensome for the DAR and the decision was made to offer the building to the Town of Oyster Bay. The Town accepted the offer and in 1947 took possession of the building and with an advisory committee made the decision to restore the front of the building to its original 18th century proportions in the 1950s.

The New York firm of Goodwin and Jaeger were responsible for the initial restoration which involved removing many of Solomon's Victorian additions.[21] The focus of the house and the interpretation were turned back to the historical events of the Revolutionary period. In 1953, with the help of the Friends of Raynham Hall, Inc., the building officially opened as a museum. The last restoration was completed in 1958 by Watland and Hopping when the front windows were realigned and the exterior siding of the Colonial saltbox refinished.

Raynham Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[22]

The written record of Raynham Hall's ghosts goes back only to the early 20th century. Julia Weeks Cole, who owned the house from 1914 to 1933, wrote an article on the ghosts for the Glen Cove Record in 1938. In her article, Miss Coles recorded the story of an overnight guest to Raynham Hall who awoke to the sounds of a ghostly white horse and a rider outside her bedroom window. Miss Coles theorized that this might have been the spectre of Major John Andre, who visited the house shortly before his capture and execution during the American Revolution. Other accounts have connected this particular ghost with the original Raynham Hall in Norfolk, England, where it is supposed to appear as a harbinger of an impending death in the family.[23]

A second incident from Miss Coles' files concerned her sister, Susan Coles Halstead, who signed a ghost descending the front stairs. She saw the spectre of an elderly man come down the stairs, turn back toward the dining room, and vanish. Mrs. Halstead stated that she was sure that the ghost was Robert Townsend, the Revolutionary War spy also known as "Culper, Jr.". What she did not explain was why Robert would be haunting a portion of the house which was not built until 13 years after his death in 1838.

Whoever the ghost on the stairs is, he may not be alone. The only recent incidents of a possibly supernatural origin have all taken place on or near the stairs. A visitor to the museum claimed to hear the swish of petticoats behind her as she walked past the base of the staircase. Turning, she was able to see just a portion of a figure, dressed in Victorian finery, go past her down the hallway toward the back of the house.[24]

Also unexplained noises have been heard throughout the house, staff members have heard distinct footsteps following them throughout the front hallway of the Victorian section of the house. Noises have been heard up in the slaves quarters which are currently used only for storage. Several unexplained smells have also been noticed in the house. From the first floor of the Colonial section staff and visitors have noticed smells of pipe tobacco and wood fire in an area where Samuel Townsend used to relax with his family in front of the fireplace with his pipe. From the kitchen the scent of apple pies baking or cinnamon have been known as a welcoming smell from the spirits to visitors of the house. And smells of roses have been noticed coming from the slave quarters.[25]

Another spectral resident made himself known back in 1999. He was first sighted looking into the garden from the servant's entrance at the rear of the house. A man, between the ages of 20 and 30 with dark curly hair. Beard and moustache, and wearing a dark coat with brass buttons. It is believed that this man is one of the Irish servants employed by the Townsend home during the Victorian period by the name of Michael Conlin. The records have been unable to confirm the name of Michael Conlin in connection with the house as the records of servants during that period were not kept very well.[26]

The main ghost story at the home revolves around the relationship of Sally Townsend with John Simcoe. She is believed to have fallen in love with Colonel Simcoe during his stay at the home during the Revolutionary War. But, at the war's end Simcoe returned to England, where he married. Sally, on the other hand, never married and died in the house, a spinster at the age of 82.[23] After her death the Valentine's latter that Simcoe had given her during his stay at the house was found with well-worn creases from countless rereadings. The room belonging to Sally is in the Colonial portion of the house known as the West Room. Many have said they noticed a change in temperature inside the room, usually about 5–10 degrees colder than the rest of the house. Some psychics and ghost hunters have come to the house and found Sally's aura to be one of sadness.[26]

Raynham Hall in Oyster Bay also shares a haunted connection with its namesake in Norfolk, England. The ancestral estate hosts The Brown Lady, first photographed in 1938 as a wispy figure descending the staircase. The Brown Lady has been spotted repeatedly since then along with other spirits of that home.

Hours of operation

Tuesday-Sunday, 1pm – 5pm. Fee: $12 adults, $8 seniors & students, youngsters under age 5 free.

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "The Townsend Family and Raynham Hall". raynhamhallmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2009-07-15. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- Oyster Bay Town Records, ed. John Cox, Jr., 6 Vols. (New York: Tobias Wright, Inc. 1930) 5:611-613.

- John Collins, notes from Trustee Simar, Raynham Hall Museum, Spring 1979.

- Raynham Hall National Register Nomination, NY State Division for Historic Preservation, Albany.

- Oyster Bay Town Records, ed. John Cox, Jr., 6 Vols. (New York: Tobias Wright, Inc. 1930) Vol. II, pp 53-55.

- Journals of the Provincial Congress, 1775-1777, Vol. I p. 517-18 cited by Dorothy H. McGee, "Raynham Hall" (Town of Oyster Bay, 1979) p. 7.

- John Graves Simcoe, Military Journal, New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844) pp. 94-95.

- "Nassau County Historical Journal" Vol. XIII, p. 49-50 cited by Dorothy H. McGee, "Raynham Hall" (Town of Oyster Bay, 1979) p.13.

- Memorial of John, Henry and Richard Townsend and their Descendants (New York: W. A. Townsend, Publisher 1865), pp. 98 and 101.

- Panes of Glass, Collection of Raynham Hall Museum, Oyster Bay.

- Letters from Robert Townsend cited by Corey Ford, A Peculiar Service (Boston: Little Brown, 1965) p. 250.

- Morton Pennypacker. General Washington's Spies. (Brooklyn: Long Island Historical Society, 1939) p.30.

- Letters from Robert Townsend cited by Corey Ford, A Peculiar Service (Boston: Little Brown, 1965) p. 170.

- Morton Pennypacker. General Washington's Spies. (Brooklyn: Long Island Historical Society, 1939) p. 44.

- Saffell, W.T.R, Records of the Revolutionary War (Baltimore: C. F. Saffell, 1894) p. 161.

- Memorial of John, Henry and Richard Townsend and their Descendants (New York: W. A. Townsend, Publisher 1865) p. 169-171.

- Davenport, Robert, Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of Cincinnati, 1783-2008 (Washington, DC: The Society of the Cincinnati) p. 351

- Memoriam to Helene DeKay Townsend, Archives, Raynham Hall, Oyster Bay, p. 3.

- Memoriam to Helene DeKay Townsend, Archives, Raynham Hall, Oyster Bay, p. 4.

- Memo to the Town of Oyster Bay from Goodwin & Jaeger 12/21/52, archives, Raynham Hall Museum.

- National Register of Historic Places, listed June 5, 1974.

- Susan Smitten, Ghost Stories of New York (Canada: Ghost House Books, 2004), 51.

- Susan Smitten, Ghost Stories of New York (Canada: Ghost House Books, 2004), 55.

- Susan Smitten, Ghost Stories of New York (Canada: Ghost House Books, 2004), 56.

- Susan Smitten, Ghost Stories of New York (Canada: Ghost House Books, 2004), 52.