Raychaudhuri equation

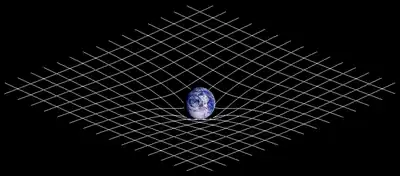

In general relativity, the Raychaudhuri equation, or Landau–Raychaudhuri equation,[1] is a fundamental result describing the motion of nearby bits of matter.

The equation is important as a fundamental lemma for the Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems and for the study of exact solutions in general relativity, but has independent interest, since it offers a simple and general validation of our intuitive expectation that gravitation should be a universal attractive force between any two bits of mass–energy in general relativity, as it is in Newton's theory of gravitation.

The equation was discovered independently by the Indian physicist Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri[2] and the Soviet physicist Lev Landau.[3]

Mathematical statement

Given a timelike unit vector field (which can be interpreted as a family or congruence of nonintersecting world lines via the integral curve, not necessarily geodesics), Raychaudhuri's equation can be written

where

are (non-negative) quadratic invariants of the shear tensor

and the vorticity tensor

respectively. Here,

is the expansion tensor, is its trace, called the expansion scalar, and

is the projection tensor onto the hyperplanes orthogonal to . Also, dot denotes differentiation with respect to proper time counted along the world lines in the congruence. Finally, the trace of the tidal tensor can also be written as

This quantity is sometimes called the Raychaudhuri scalar.

Intuitive significance

The expansion scalar measures the fractional rate at which the volume of a small ball of matter changes with respect to time as measured by a central comoving observer (and so it may take negative values). In other words, the above equation gives us the evolution equation for the expansion of the timelike congruence. If the derivative (with respect to proper time) of this quantity turns out to be negative along some world line (after a certain event), then any expansion of a small ball of matter (whose center of mass follows the world line in question) must be followed by recollapse. If not, continued expansion is possible.

The shear tensor measures any tendency of an initially spherical ball of matter to become distorted into an ellipsoidal shape. The vorticity tensor measures any tendency of nearby world lines to twist about one another (if this happens, our small blob of matter is rotating, as happens to fluid elements in an ordinary fluid flow which exhibits nonzero vorticity).

The right hand side of Raychaudhuri's equation consists of two types of terms:

- terms which promote (re)-collapse

- initially nonzero expansion scalar,

- nonzero shearing,

- positive trace of the tidal tensor; this is precisely the condition guaranteed by assuming the strong energy condition, which holds for the most important types of solutions, such as physically reasonable fluid solutions,

- terms which oppose (re)-collapse

- nonzero vorticity, corresponding to Newtonian centrifugal forces,

- positive divergence of the acceleration vector (e.g., outward pointing acceleration due to a spherically symmetric explosion, or more prosaically, due to body forces on fluid elements in a ball of fluid held together by its own self-gravitation).

Usually one term will win out. However, there are situations in which a balance can be achieved. This balance may be:

- stable: in the case of hydrostatic equilibrium of a ball of perfect fluid (e.g. in a model of a stellar interior), the expansion, shear, and vorticity all vanish, and a radial divergence in the acceleration vector (the necessary body force on each blob of fluid being provided by the pressure of surrounding fluid) counteracts the Raychaudhuri scalar, which for a perfect fluid is in geometrized units. In Newtonian gravitation, the trace of the tidal tensor is ; in general relativity, the tendency of pressure to oppose gravity is partially offset by this term, which under certain circumstances can become important.

- unstable: for example, the world lines of the dust particles in the Gödel solution have vanishing shear, expansion, and acceleration, but constant vorticity just balancing a constant Raychuadhuri scalar due to nonzero vacuum energy ("cosmological constant").

Focusing theorem

Suppose the strong energy condition holds in some region of our spacetime, and let be a timelike geodesic unit vector field with vanishing vorticity, or equivalently, which is hypersurface orthogonal. For example, this situation can arise in studying the world lines of the dust particles in cosmological models which are exact dust solutions of the Einstein field equation (provided that these world lines are not twisting about one another, in which case the congruence would have nonzero vorticity).

Then Raychaudhuri's equation becomes

Now the right hand side is always negative or zero, so the expansion scalar never increases in time.

Since the last two terms are non-negative, we have

Integrating this inequality with respect to proper time gives

If the initial value of the expansion scalar is negative, this means that our geodesics must converge in a caustic ( goes to minus infinity) within a proper time of at most after the measurement of the initial value of the expansion scalar. This need not signal an encounter with a curvature singularity, but it does signal a breakdown in our mathematical description of the motion of the dust.

Optical equations

There is also an optical (or null) version of Raychaudhuri's equation for null geodesic congruences.

- .

Here, the hats indicate that the expansion, shear and vorticity are only with respect to the transverse directions. When the vorticity is zero, then assuming the null energy condition, caustics will form before the affine parameter reaches .

Applications

The event horizon is defined as the boundary of the causal past of null infinity. Such boundaries are generated by null geodesics. The affine parameter goes to infinity as we approach null infinity, and no caustics form until then. So, the expansion of the event horizon has to be nonnegative. As the expansion gives the rate of change of the logarithm of the area density, this means the event horizon area can never go down, at least classically, assuming the null energy condition.

See also

- Congruence (general relativity), for a derivation of the kinematical decomposition and of Raychaudhuri's equation

- Gravitational singularity

- Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems for an application of the focusing theorem

Notes

- Spacetime as a deformable solid, M. O. Tahim, R. R. Landim, and C. A. S. Almeida, arXiv:0705.4120v1.

- Dadhich, Naresh (August 2005). "Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri (1923–2005)" (PDF). Current Science. 89: 569–570.

- The large scale structure of space-time by Stephen W. Hawking and G. F. R. Ellis, Cambridge University Press, 1973, p. 84, ISBN 0-521-09906-4.

References

- Poisson, Eric (2004). A Relativist's Toolkit: The Mathematics of Black Hole Mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83091-5. See chapter 2 for an excellent discussion of Raychaudhuri's equation for both timelike and null geodesics, as well as the focusing theorem.

- Carroll, Sean M. (2004). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity. San Francisco: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-8053-8732-3. See appendix F.

- Stephani, Hans; Kramer, Dietrich; MacCallum, Malcolm; Hoenselaers, Cornelius; Hertl, Eduard (2003). Exact Solutions to Einstein's Field Equations (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46136-7. See chapter 6 for a very detailed introduction to geodesic congruences, including the general form of Raychaudhuri's equation.

- Hawking, Stephen & Ellis, G. F. R. (1973). The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09906-4. See section 4.1 for a discussion of the general form of Raychaudhuri's equation.

- Raychaudhuri, A. K. (1955). "Relativistic cosmology I.". Phys. Rev. 98 (4): 1123–1126. Bibcode:1955PhRv...98.1123R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.98.1123. hdl:10821/7599. Raychaudhuri's paper introducing his equation.

- Dasgupta, Anirvan; Nandan, Hemwati & Kar, Sayan (2009). "Kinematics of geodesic flows in stringy black hole backgrounds". Phys. Rev. D. 79 (12): 124004. arXiv:0809.3074. Bibcode:2009PhRvD..79l4004D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.79.124004. S2CID 118628925. See section IV for derivation of the general form of Raychaudhuri equations for three kinematical quantities (namely expansion scalar, shear and rotation).

- Kar, Sayan & SenGupta, Soumitra (2007). "The Raychaudhuri equations: A Brief review". Pramana. 69 (1): 49–76. arXiv:gr-qc/0611123. Bibcode:2007Prama..69...49K. doi:10.1007/s12043-007-0110-9. S2CID 119438891. See for a review on Raychaudhuri equations.

External links

- The Meaning of Einstein's Field Equation by John C. Baez and Emory F. Bunn. Raychaudhuri's equation takes center stage in this well known (and highly recommended) semi-technical exposition of what Einstein's equation says.

- Theoretical Cosmology by Raychaudhuri, A. K. Clarendon Press, 1979 https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Theoretical_Cosmology.html?id=p1DApKmlaFoC&redir_esc=y