Maze

A maze is a path or collection of paths, typically from an entrance to a goal. The word is used to refer both to branching tour puzzles through which the solver must find a route, and to simpler non-branching ("unicursal") patterns that lead unambiguously through a convoluted layout to a goal. The term "labyrinth" is generally synonymous with "maze", but can also connote specifically a unicursal pattern.[1] The pathways and walls in a maze are typically fixed, but puzzles in which the walls and paths can change during the game are also categorised as mazes or tour puzzles.

| Part of a series on |

| Puzzles |

|---|

|

Construction

Mazes have been built with walls and rooms, with hedges, turf, corn stalks, straw bales, books, paving stones of contrasting colors or designs, and brick,[2] or in fields of crops such as corn or, indeed, maize. Maize mazes can be very large; they are usually only kept for one growing season, so they can be different every year, and are promoted as seasonal tourist attractions.

Indoors, mirror mazes are another form of maze, in which many of the apparent pathways are imaginary routes seen through multiple reflections in mirrors. Another type of maze consists of a set of rooms linked by doors (so a passageway is just another room in this definition). Players enter at one spot, and exit at another, or the idea may be to reach a certain spot in the maze. Mazes can also be printed or drawn on paper to be followed by a pencil or fingertip. Mazes can be built with snow.

Quality conventions for designing mazes differ according to the medium each maze is to be rendered in: Mazes to be walked by people should not reveal a closed end from a primary branch point, so that any person traversing the maze must walk further, in order to determine if a turn leads to a viable path. Mazes traced on paper typically use long, mostly parallel, convoluted routes, even for paths that are dead ends, so that a person tracing the maze has difficulty identifying dead ends while the pencil is set at a branch point.

Generation

Maze generation is the act of designing the layout of passages and walls within a maze. There are many different approaches to generating mazes, with various maze generation algorithms for building them, either by hand or automatically by computer.

There are two main mechanisms used to generate mazes. In "carving passages", one marks out the network of available routes. In building a maze by "adding walls", one lays out a set of obstructions within an open area. Most mazes drawn on paper are done by drawing the walls, with the spaces in between the markings composing the passages.

Solution

Maze solving is the act of finding a route through the maze from the start to finish. Some maze solving methods are designed to be used inside the maze by a traveler with no prior knowledge of the maze, whereas others are designed to be used by a person or computer program that can see the whole maze at once.

The mathematician Leonhard Euler was one of the first to analyze plane mazes mathematically, and in doing so made the first significant contributions to the branch of mathematics known as topology.

Mazes containing no loops are known as "standard", or "perfect" mazes, and are equivalent to a tree in graph theory. Thus many maze solving algorithms are closely related to graph theory. Intuitively, if one pulled and stretched out the paths in the maze in the proper way, the result could be made to resemble a tree.[3]

Psychology experiments

Mazes are often used in psychology experiments to study spatial navigation and learning. Such experiments typically use rats or mice. Examples are:

Types

- Ball-in-a-maze puzzles

- Dexterity puzzles which involve navigating a ball through a maze or labyrinth.

- Block maze

- A maze in which the player must complete or clear the maze pathway by positioning blocks. Blocks may slide into place or be added.

- Fractal maze

- A maze containing holes inside which the maze is indefinitely repeated at a smaller scale.[4]

- Hamilton maze

- A maze in which the goal is to find the unique Hamiltonian cycle.[5][6]

- Linear or railroad maze

- A maze in which the paths are laid out like a railroad with switches and crossovers. Solvers are constrained to moving only forward. Often, a railroad maze will have a single track for entrance and exit.

- Logic mazes

- These are like standard mazes except they use rules other than "don't cross the lines" to restrict motion.

- Loops and traps maze

- A maze that features one-way doors. One must find the correct sequence of doors to escape.

- Number maze

- A maze in which numbers are used to determine jumps that form a pathway, allowing the maze to criss-cross itself many times.

- Picture maze

- A standard maze that forms a picture when solved.

- Turf mazes and mizmazes

- A pattern like a long rope folded up, without any junctions or crossings.

Gallery

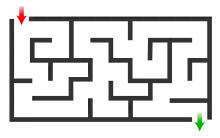

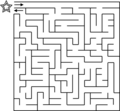

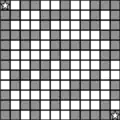

Standard maze: Find a path from and back to the star.

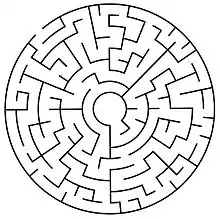

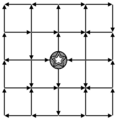

Standard maze: Find a path from and back to the star. Circular maze type: Find a route to the centre of the maze.

Circular maze type: Find a route to the centre of the maze. Loops and traps maze: Follow the arrows from and back to the star

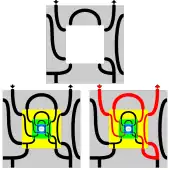

Loops and traps maze: Follow the arrows from and back to the star Block maze: Fill in four blocks to make a road connecting the stars. No diagonals.

Block maze: Fill in four blocks to make a road connecting the stars. No diagonals. Number maze: Begin and end at the star. Using the number in your space, jump that number of blocks in a straight line to a new space. No diagonals.

Number maze: Begin and end at the star. Using the number in your space, jump that number of blocks in a straight line to a new space. No diagonals.

Publications

Numerous mazes of different kinds have been drawn, painted, published in books and periodicals, used in advertising, in software, and sold as art. In the 1970s there occurred a publishing "maze craze" in which numerous books, and some magazines, were commercially available in nationwide outlets and devoted exclusively to mazes of a complexity that was able to challenge adults as well as children (for whom simple maze puzzles have long been provided both before, during, and since the 1970s "craze").

Some of the best-selling books in the 1970s and early 1980s included those produced by Vladimir Koziakin,[7] Rick and Glory Brightfield, Dave Phillips, Larry Evans, and Greg Bright. Koziakin's works were predominantly of the standard two-dimensional "trace a line between the walls" variety. The works of the Brightfields had a similar two-dimensional form but used a variety of graphics-oriented "path obscuring" techniques. Although the routing was comparable to or simpler than Koziakin's mazes, the Brightfields' mazes did not allow the various pathway options to be discerned easily by the roving eye as it glanced about.

Greg Bright's works went beyond the standard published forms of the time by including "weave" mazes in which illustrated pathways can cross over and under each other. Bright's works also offered examples of extremely complex patterns of routing and optical illusions for the solver to work through. What Bright termed "mutually accessible centers" (The Great Maze Book, 1973) also called "braid" mazes, allowed a proliferation of paths flowing in spiral patterns from a central nexus and, rather than relying on "dead ends" to hinder progress, instead relied on an overabundance of pathway choices. Rather than have a single solution to the maze, Bright's routing often offered multiple equally valid routes from start to finish, with no loss of complexity or diminishment of solver difficulties because the result was that it became difficult for a solver to definitively "rule out" a particular pathway as unproductive. Some of Bright's innovative mazes had no "dead ends", although some clearly had looping sections (or "islands") that would cause careless explorers to keep looping back again and again to pathways they had already travelled.

The books of Larry Evans focused on 3-D structures, often with realistic perspective and architectural themes, and Bernard Myers (Supermazes No. 1) produced similar illustrations. Both Greg Bright (The Hole Maze Book) and Dave Phillips (The World's Most Difficult Maze) published maze books in which the sides of pages could be crossed over and in which holes could allow the pathways to cross from one page to another, and one side of a page to the other, thus enhancing the 3-D routing capacity of 2-D printed illustrations.

Adrian Fisher is both the most prolific contemporary author on mazes, and also one of the leading maze designers.[8] His book The Amazing Book of Mazes (2006) contains examples and photographs of numerous methods of maze construction, several of which have been pioneered by Fisher; The Art of the Maze (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1990) contains a substantial history of the subject, whilst Mazes and Labyrinths (Shire Publications, 2004) is a useful introduction to the subject.

A recent book by Galen Wadzinski (The Ultimate Maze Book) offers formalized rules for more recent innovations that involve single-directional pathways, 3-D simulating illustrations, "key" and "ordered stop" mazes in which items must be collected or visited in particular orders to add to the difficulties of routing (such restrictions on pathway traveling and re-use are important in a printed book in which the limited amount of space on a printed page would otherwise place clear limits on the number of choices and pathways that can be contained within a single maze). Although these innovations are not all entirely new with Wadzinski, the book marks a significant advancement in published maze puzzles, offering expansions on the traditional puzzles that seem to have been fully informed by various video game innovations and designs, and adds new levels of challenge and complexity in both the design and the goals offered to the puzzle-solver in a printed format.

Public attractions

Japan

Austria

- Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, has a large hedge maze in its gardens.

- Swarovski Crystal World, Wattens, Tyrol, has a hand-shaped hedge maze in its gardens.

Belgium

- Loppem Castle maze

Czech republic

- Obludiste , Dolni Pena (Jindrichuv Hradec) - hedge maze 6.000 m2

Germany

- Hortus Vitalis – Der Irrgarten,[16] Bad Salzuflen (hedge maze)

Greece

- Labyrinth Park near Hersonissos, Crete (extends to approximately 1.300 m2)[17][18]

Italy

- Castello di Masino, Caravino 10010, Torino, Italia

- Porsenna's Maze,[19] Chiusi, Tuscany (see Pliny's Italian labyrinth)

- Villa Pisani, Stra, near Venice (45.409587°N 12.013131°E)

- The labyrinth of Franco Maria Ricci at Fontanellato[20] (44.853989°N 10.146446°E)

Netherlands

- Waterlabyrinth, Nijmegen, designed by Klaus van de Locht, 1981[21] (51.85016°N 5.860471°E)

- Doolhof Ruurlo, Ruurlo, designed by Daniel Marot, based on the design for Hampton Court Maze[22] (52.078266°N 6.433654°E)

Portugal

- Parque do Arnado,[23] Ponte de Lima, District of Viana do Castelo

- Parque de São Roque,[24] District of Porto[25]

- Forest Reserve of Pinhal da Paz,[26] São Miguel Island, Azores

Spain

- Alcázar of Seville, Seville

- Corn Laberynth in the Camino de Santiago, León[27]

- Parc del laberint d'Horta, Barcelona,[28] (41.440235°N 2.145769°E)

- Parc de la Torreblanca, Esplugues de Llobregat (41.37856°N 2.054628°E)

- Parque de El Capricho, Madrid

- Laberinto de Villapresente,[29] Cantabria. With 5,625qm, it is the largest maze in Spain.

- Parque de Tentegorra,[30] Murcia

- Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso,[31] Segovia (40.5352°N 3.5956°W)

United Kingdom

- Blake House Craft Centre, Braintree, Essex, England (Open July–September)[32][33]

- Carnfunnock Country Park, Northern Ireland. A hedge maze in the shape of Northern Ireland and winner of 1985 Design a Maze competition.[34]

- Castlewellan, Northern Ireland, world's largest permanent hedge maze[35][36]

- Chatsworth House garden maze, planted with 1,209 yews.

- Cliveden House Originally laid out in 1894, the maze was restored and re-opened to the public in 2011, consisting of 1100 Yew trees.

- Crystal Palace Park, South London. Laid out in the 1870s, this is the largest maze in London.[37]

- Glendurgan Garden, Cornwall. A cherry laurel hedge maze created in 1833.[38]

- Hampton Court Maze. A famous historic maze in the Palace gardens.[39]

- Hever Castle Maze, Hever, Kent. Yew tree maze and a splashing water maze[40]

- Hoo Hill Maze, Shefford, Bedfordshire, England[41][42]

- Norwich Cathedral, Norfolk, England. A labyrinth in the Cloister Garth. Laid to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of HM Queen Elizabeth II in 2002.[43]

- Richings Park Amazing Maize Maze, Richings Park, near Heathrow, England (Open July–September)[44]

- Saffron Walden, an Essex town with its historic Bridge End Gardens hedge maze and the England's largest turf maze[45]

- Saltwell Park, Gateshead, Tyne and Wear, England. A yew-tree maze restored to its original condition in 2005 and open to the public during park opening hours.[46]

- Somerleyton Hall, Suffolk, England. A yew hedge maze designed and planted in 1846 by William Nesfield.[47]

- Traquair House, Peeblesshire, Scotland. A beech tree hedge maze designed by John Schofield.[48]

- York Maze, near RAF Elvington, with a different design each year

North America

.jpg.webp)

Canada

- In 2012, the Kraay Family Farm in Alberta, Canada created the world's largest QR code in the form of a massive corn maze, popularly known as The Edmonton Corn Maze.[49][50]

United States

- The Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, Colorado in 2015 installed a 10,100-square-foot hedge maze on its front lawn, using 1,600 to 2,000 Alpine Currant hedge bushes. Previously the hotel had no maze, though one was featured prominently in the 1980 film adaption of Stephen King's novel The Shining, which is set at the hotel.[51][52]

- Dole Pineapple Plantation, Oahu.

- Tanglewood Music Center Hedge Maze, Lenox and Stockbridge, Massachusetts.[53]

- Mazes are a popular attraction at Renaissance Festivals across the United States.[54]

- The Wooz was a maze attraction opened in 1988 in Vacaville, California by Sun Creative System, a Japanese company that had seen success with the concept in Japan. Despite initial interest, high admission cost and hot summers led the park to close in 1992. The failure of the Wooz scuttled Sun Creative System's plans for additional maze attractions in the U.S.[55]

South Africa

Chartwell Castle in Johannesburg claims to have the biggest known uninterrupted hedgerow maze in the Southern world, with over 900 conifers. It covers about 6000 sq.m. (approximately 1.5 acres), which is around 5 times bigger than The Hampton Court Maze. The center is about 12m × 12m. The maze was designed and laid out by Conrad Penny.[56]

Cuba

The colonial city of Camagüey, Cuba, founded in 1528, layout resembles a real maze, with narrow, short streets always turning in one direction or another. After pirate Henry Morgan burned the city in the 17th century, it was designed like a maze so attackers would find it hard to move around inside the city. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Brazil

- Labirinto Verde,[57] Nova Petrópolis, (Circular hedge maze built in 1989; Latitude 29°22'32.71"S Longitude 51°06'43.68"W)

In popular culture

Television

- Both Nubeluz and American Gladiators, from Peru and the United States respectively, featured a giant life-size maze used in competition. The object on both programs was for the contestants to find their way from the entrance to the exit as quickly as possible. On Nubeluz, the contestants took turns running through the maze and had a maximum of 1 minute to reach the exit;[58] on American Gladiators, both contestants ran through the maze simultaneously and were given 45 seconds to find the correct solution.[59] The giant maze was part of the game rotation on both programs concurrently, and was also retired from both programs simultaneously.

The Shining

- The film adaptation of Stephen King's 1977 novel, The Shining (1980), includes a scene featuring Jack Torrance and Danny Torrance in a hedge maze.[51][52]

References

- Hermann Kern (2000). Through the labyrinth: designs and meanings over 5000 years. Prestel. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-7913-2144-8. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014.

- "Trevithick Brick Path Maze". Lappa Valley Steam Railway. Archived from the original on 12 August 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- Maze to Tree Archived 12 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. YouTube (23 December 2007). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- "Fractal Maze - Wolfram Demonstrations Project".

- de Ruiter, Johan (2017). Hamilton Mazes - The Beginner's Guide.

- Friedman, Erich (2009). "Hamiltonian Mazes". Erich's Puzzle Palace. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- Mazes, Vladimir Koziakin (Grosset & Dunlap, 1971) ISBN 0-448-01836-5

- Twilley, Nicola (18 November 2021). "How the World's Foremost Maze-Maker Leads People Astray". The New Yorker. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- Retail Arabia to open French hypermarket Géant in The Gardens Shopping Mall | Nakheel Properties Archived 2 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. AMEinfo.com. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- welcome to hikimi town!! Archived 13 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Iwami.or.jp. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- 巨大迷路パラディアム Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Kinugawa.ne.jp. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- 仙台ハイランド ホームページ Archived 14 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Hi-land.co.jp. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- ::白浜エネルギーランド:: 移転連絡 Archived 7 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Royalpines.co.jp. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Samsø Labyrinten – verdens største labyrint Archived 22 April 2003 at the Wayback Machine. Samsolabyrinten.com. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Google Maps. Maps.google.com.au (1 January 1970). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Hortus Vitalis – Irrgarten und Erlebniswelt – Ausflugsziel in Bad Salzuflen Archived 13 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Hortus-vitalis.de. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Labyrinth Park Archived 24 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 26 April 2017.

- Google Maps. Maps.google.com.au (1 January 1970). Retrieved on 26 April 2017.

- "Nuova pagina 0". Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- "Italian creates world's largest maze". TheGuardian.com. 4 July 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016.

- "Het Labyrinth". klausvandelocht.nl. Archived from the original on 2 October 2010.

- "Doolhof van Ruurlo – geschiedenis". Archived from the original on 1 August 2012.

- Jardins no Parque do Arnado Archived 3 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Ponte de Lima. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- C.M. Porto Archived 18 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Cm-porto.pt. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Google Maps. Maps.google.com.au (1 January 1970). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Reserva Florestal de Recreio do Pinhal da Paz (São Miguel) Archived 19 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Azores.gov.pt. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- "León cuenta con un laberinto único en el mundo. nortecastilla.es". www.elnortedecastilla.es. 22 September 2008.

- "Parc del Laberint d'Horta". Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Identificación". Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Palacio Real de la Granja de San Ildefonso". Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- maze Archived 14 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Greatmaze.info. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Google Maps. Maps.google.com.au (1 January 1970). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- "Carnfunnock Maze". Larne Borough Council. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Records Search Page Archived 8 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Guinness World Records. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Google Maps. Maps.google.com.au (1 January 1970). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- London's Labyrinths and Mazes Archived 21 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine Londonist. Retrieved on 20 November 2016.

- Glendurgan Garden Archived 20 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. National Trust (17 November 2005). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Palaces, Historic Royal. "Lose Yourself in the Famous, Fun-Filled Hampton Court Maze - Historic Royal Palaces". Archived from the original on 29 July 2012.

- "Mazes - Hever Castle". Archived from the original on 2 March 2012.

- Hoo Hill Maze Archived 20 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Wuff.me.uk. Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Google Maps. Maps.google.com.au (1 January 1970). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- Norwich Cathedral Labyrinth Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Norwich Cathedral. Retrieved on 4 April 2012.

- The Maize Maze Archived 22 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Farmmaze.co.uk (10 July 2005). Retrieved on 18 June 2011.

- "The Essex town where you can do five amazing outdoor mazes in a day". 18 February 2019.

- "Would yew enjoy maize?". Evening Chronicle. 19 January 2005. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Somerleyton Hall and Gardens Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Somerleyton Estate. Retrieved on 4 April 2012.

- "The Traquair maze".

- Kooser, Amanda (11 September 2012). "World's largest QR code is a Canadian corn maze". CNet. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- Kooser, Amanda (4 September 2013). "Navigate this massive corn maze using Google Street View". CNet.

- Kooser, Amanda (9 January 2015). "'The Shining' hotel wants you to design a hedge maze for it". CNet. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- "'The Shining' Hotel to Finally Get a Real Hedge Maze". Construction Equipment Guide. 26 May 2015. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015.

- "Music in the Berkshires: Classical Beyond Tanglewood, Part 3". Hampton Terrace. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- "I Entered A Renaissance Festival Maze". Sir Guy of Warwick.

- Dowd, Katie (17 June 2021). "The history of the hottest, most ill-advised theme park ever made: The Wooz". sfgate.com. SFGATE. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- "Maze". Chartwell Castle. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- WEBDE.COM.BR. "Município de Nova Petrópolis - Empresa". Archived from the original on 30 September 2011.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O43hZ3piBZQ A segment of an early 1992 episode of Nubeluz featuring the maze. The first player's turn begins at the top of the segment; the second player's turn begins at 5:20.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWB3x6rVmQw The maze featured on American Gladiators.

Further reading

- Ettore Selli, "Labirinti Vegetali, la guida completa alle architetture verdi dei cinque continenti", Ed. Pendragon, 2020; ISBN 9788833642222

- Abelson, H.; diSessa, A. (1980). Turtle Geometry: The Computer as a Medium for Exploring Mathematics. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262010634.

- Fisher, Adrian (2006). The Amazing Book of Mazes. London: Thames & Hudson and New York: Harry N Abrams Inc. ISBN 978-0-500-51247-0.

- Fisher, Adrian; Gerster, Georg (1990). The Art of the Maze. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-83027-9.

- Fisher, Adrian & Loxton, Howard (1997). Secrets of the Maze. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01811-8.

- Fisher, Adrian; Saward, Jeff (1991). The British Maze Guide. St Albans, UK: Minotaur Designs. The definitive guide to British Mazes.

- Martineau, John Southcliffe (2005). Mazes and Labyrinths: In Great Britain. Wooden Books. ISBN 978-1-904263-33-3.

- Matthews, W. H. (1927). Mazes and Labyrinths: Their History and Development. Includes "Bibliography". Mazes and Labyrinths. Dover Publications. 1970. ISBN 0-486-22614-X.

- Saward, Jeff (2002). Magical Paths. Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 1-84000-573-4.

External links

Media related to Mazes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mazes at Wikimedia Commons- "Britain's best mazes". Times Online. 21 August 2006.

- Labyrinth Society official web page

- Neild, Barry (29 September 2006). "Shortcuts: Escaping a maze". CNN Briefing Room.