Novara-class cruiser

The Novara class (sometimes called the Helgoland class[1] or the Admiral Spaun class[2][lower-alpha 1]) was a class of three scout cruisers built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Named for the Battle of Novara, the class comprised SMS Saida, SMS Helgoland, and SMS Novara. Construction started on the ships shortly before World War I; Saida and Helgoland were both laid down in 1911, Novara followed in 1912. Two of the three warships were built in the Ganz-Danubius shipyard in Fiume; Saida was built in the Cantiere Navale Triestino shipyard in Monfalcone. The Novara-class ships hold the distinction for being the last cruisers constructed by the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

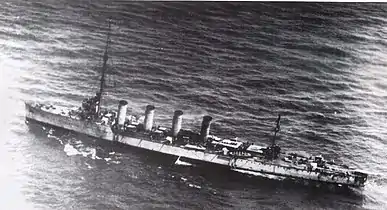

Novara, after the Battle of the Otranto Straits | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Novara class |

| Builders | |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Admiral Spaun |

| Built | 1911–1915 |

| In service | 1914–1941 |

| In commission | 1914–1937 |

| Completed | 3 |

| Scrapped | 3 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Scout cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 130.6 m (428 ft 6 in) o/a |

| Beam | 12.77 m (41 ft 11 in) |

| Draught | 4.95–5.3 m (16 ft 3 in – 17 ft 5 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts; 2 × steam turbines |

| Speed | 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) |

| Range | 1,600 nautical miles (3,000 km; 1,800 mi) at 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) |

| Complement | 340 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Saida and Helgoland were commissioned into the fleet in the opening weeks of World War I, in August and September 1914, respectively. Novara followed in January 1915. All three ships saw limited action during the first year of the war, and following Italy's declaration of war on Austria-Hungary in May 1915, the ships participated in a bombardment of the Italian coastline. Throughout the rest of 1915, the Novara-class cruisers engaged in various operations across the Adriatic Sea and the Strait of Otranto.

All of the Novaras were assigned to the First Torpedo Flotilla of the Austro-Hungarian Navy upon their commissioning, with Saida named the flotilla leader. and were initially stationed out of the naval base at Sebenico, before eventually being deployed to Cattaro. Throughout the rest of 1915 and 1916, all three ships saw extensive combat in several raids directed at the Otranto Barrage which prohibited the bulk of the Austro-Hungarian Navy from leaving the Adriatic Sea. These actions culminated in the Battle of the Strait of Otranto in May 1917, where the Novaras participated in the largest surface engagement of the Adriatic Campaign of World War I. The ensuing battle resulted in an Austro-Hungarian victory, though Novara suffered damage.

Emboldened by this operation and determined to break the Otranto Barrage with a major attack on the strait, Austria-Hungary's newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet (German: Flottenkommandant) Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya organized a massive attack on the Allied forces with the three Novara-class cruisers, alongside seven battleships, one cruiser, four destroyers, four torpedo boats, and numerous submarines and aircraft, but the operation was abandoned after the battleship Szent István was sunk by the motor torpedo boat MAS-15 on the morning of 10 June.

After the sinking of Szent István, the ships returned to port where they remained for the rest of the war. When Austria-Hungary was facing defeat in October 1918, the Austrian government transferred its navy to the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs in order to avoid having to hand the ship over to the Allies. Following the Armistice of Villa Giusti in November 1918, the Novara-class cruisers were divided between Italy and France, with Saida and Helgoland both being ceded to the Italians before being renamed Venezia and Brindisi respectively, while Novara was handed over to France and renamed Thionville. The Novara-class cruisers were the largest ships of Austro-Hungarian Navy to serve under the flag of another nation after the war, having been transferred to the victors.[3] After serving in the Italian Regia Marina for 17 years, Venezia and Brindisi were sold for scrap in March 1937; Thionville was decommissioned from the French Navy in 1932 and broken up for scrap in 1941.

Background

In 1904, the Austro-Hungarian Navy consisted of 10 battleships of various types, three armored cruisers, six protected cruisers, eight torpedo vessels, and 68 torpedo craft. The total tonnage of the navy was 131,000 tonnes (129,000 long tons; 144,000 short tons).[4] While the navy was capable of defending the coastline of Austria-Hungary, it was drastically outclassed by other major Mediterranean navies, namely Italy and the United Kingdom.[5] Following the establishment of the Austrian Naval League in September 1904,[lower-alpha 2] and the October appointment of Vice-Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli to the posts of Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (German: Marinekommandant) and Chief of the Naval Section of the War Ministry (German: Chef der Marinesektion),[6][7] the Austro-Hungarian Navy began an expansion program suitable for that of a Great Power. Montecuccoli immediately pursued the efforts championed by his predecessor, Admiral Hermann von Spaun, and pushed for a greatly expanded and modernized navy.[8]

The Novara-class cruisers were developed at a time when Austria-Hungary's naval policy began to shift away from simply coastal defense, to projecting power into the Adriatic and even Mediterranean Seas. This change in policy was motivated by both internal and external factors. New railroads had been constructed through Austria's Alpine passes between 1906 and 1908, linking Trieste and the Dalmatian coastline to the rest of the Empire and providing the interior of Austria-Hungary with quicker access to the sea than ever before. Lower tariffs on the port of Trieste aided the expansion of the city and a similar growth in Austria-Hungary's merchant marine. These changes necessitated the development of a new line of battleships capable of more than the defense of Austria-Hungary's coastline.[9] Prior to the turn of the century, sea power had not been a priority in Austrian foreign policy, and the navy had little public interest or support. The appointment of Archduke Franz Ferdinand – heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and a prominent and influential supporter of naval expansion – to the position of admiral in September 1902 greatly increased the importance of the navy in the eyes of both the general public and the Austrian and Hungarian Parliaments.[10][11] Franz Ferdinand's interest in naval affairs stemmed primarily from his belief that a strong navy would be necessary to compete with Italy, which he viewed as Austria-Hungary's greatest regional threat.[12]

Austro-Italian naval arms race

The Novara-class cruisers were authorized when Austria-Hungary was engaged in a naval arms race with its nominal ally, Italy.[13][14] Italy's Regia Marina was considered the most-important naval power in the region which Austria-Hungary measured itself against, often unfavorably. The disparity between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian navies had existed for decades; in the late 1880s Italy boasted the third-largest fleet in the world, behind the French Navy and the British Royal Navy.[15] While that disparity had been somewhat equalized with the Imperial Russian Navy and the German Imperial Navy surpassing the Italian Navy in 1893 and in 1894,[16] by 1904 the balance began to shift towards Italy's favor once more.[17] Indeed, by 1904 the size of the Italian Regia Marina was by tonnage was over twice that of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, and while the two nations had relatively even numbers of battleships, Italy had over twice as many cruisers.[18]

| Naval strength of Italy and Austria-Hungary in 1904[18][lower-alpha 3] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Italy | Austria-Hungary | Italian/Austro-Hungarian

tonnage ratio | ||

| Number | Tonnage | Number | Tonnage | ||

| Battleships | 13 | 166,724 tonnes (164,091 long tons; 183,782 short tons) | 10 | 85,560 tonnes (84,209 long tons; 94,314 short tons) | 1.9:1 |

| Armored cruisers | 6 | 39,903 tonnes (39,273 long tons; 43,986 short tons) | 3 | 18,810 tonnes (18,513 long tons; 20,734 short tons) | 2.1:1 |

| Protected cruisers | 14 | 37,393 tonnes (36,802 long tons; 41,219 short tons) | 6 | 17,454 tonnes (17,178 long tons; 19,240 short tons) | 2.1:1 |

| Torpedo vessels | 15 | 12,848 tonnes (12,645 long tons; 14,162 short tons) | 8 | 5,070 tonnes (4,990 long tons; 5,589 short tons) | 2.5:1 |

| Torpedo Craft | 145 | 10,477 tonnes (10,312 long tons; 11,549 short tons) | 68 | 4,252 tonnes (4,185 long tons; 4,687 short tons) | 2.4:1 |

| Total | 195 | 267,345 tonnes (263,123 long tons; 294,697 short tons) | 95 | 131,246 tonnes (129,173 long tons; 144,674 short tons) | 2.3:1 |

Proposals

The Novara-class ships were first conceived on paper in early 1905 when Montecuccoli drafted his first proposal for a modern Austrian fleet as part of his plan to construct a navy large enough to contest the Adriatic Sea. This initial plan consisted of 12 battleships, four armored cruisers, eight scout cruisers, 18 destroyers, 36 high seas torpedo craft, and 6 submarines. While specifics had yet to be drawn up, the four cruisers in Montecuccoli's plan would ultimately become Admiral Spaun and the three ships of the Novara class.[19][20] While the Austrian and Hungarian Delegations for Common Affairs approved Montecuccoli's program in part at the end of 1905, the budget only included for the three Erzherzog Karl-class battleships, the cruiser Admiral Spaun, and six destroyers. While Montecuccoli's 1907 naval budget was able to secure funding for Admiral Spaun, it was not until 1909 that the Novara-class cruisers made it from the drawing board into the navy's budget.[21]

Taking advantage of political support for naval expansion he had obtained in both Austria and Hungary since coming into office, and Austrian fears of a war with Italy over the Bosnian Crisis during the previous year, Montecuccoli drafted a new memorandum to Emperor Franz Joseph I in January 1909 proposing an enlarged Austro-Hungarian Navy consisting of 16 battleships, 12 cruisers, 24 destroyers, 72 seagoing torpedo boats, and 12 submarines. This memorandum was essentially a modified version of his 1905 plan, though notable changes included four additional dreadnought battleships with a displacement of 20,000 tonnes (19,684 long tons) at load which would later become the Tegetthoff-class battleships as well as three cruisers modeled after Admiral Spaun, which was nearing completion. These three ships would each have a displacement of 3,500 tonnes (3,400 long tons; 3,900 short tons).[22][23]

The subsequent leaking of this proposal to the general press led to an intensification of the naval arms race between Austria-Hungary and Italy, and diverted most public attention towards the competing dreadnought battleship proposals emerging from both Vienna and Rome.[22] Nevertheless, Montecuccoli did not neglect the other aspects of his proposed program and in September 1909 he proposed to the Austro-Hungarian Ministerial Council a budget for 1910 which would authorize construction on the three cruisers of the Novara class, alongside the four dreadnoughts of the Tegetthoff class and several torpedo boats and submarines. Once again, Montecuccoli's desire to construct a new class of cruisers was delayed, this time due to the financial costs Austria-Hungary took on following the annexation of Bosnia and the mobilization of her fleet and army at the height of the diplomatic crisis stemming from the annexation. Rather than being given the funding needed to begin construction on the Novara-class cruisers, the navy was instead given funds only to speed up completion of the Radetzky-class battleships and Admiral Spaun.[24]

Budget negotiations

Faced with another setback, Montecuccoli drafted a second memorandum to Emperor Franz Joseph I on 30 May 1910, once again calling for a strengthened navy which included three Novara-class cruisers. Recent developments following the Bosnian Crisis, such as Italy's announced naval expansion, the construction of the new Italian dreadnought battleship Dante Alighieri, and the modernization of Italy's torpedo flotilla all led Montecuccoli to warn the Emperor that the navy would be unable to protect Austria-Hungary's coastline, barring the "urgent and quickest possible completion" of his naval expansion program. This program included four proposed Tegetthoff-class battleships, the three Novara-class cruisers, six destroyers, 12 torpedo boats, six submarines, and four river monitors to patrol the Danube. Montecuccoli's plans were to cost 330 million Kronen and would be completed by 1915.[25]

The Emperor supported this proposal and his support, combined with that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the Austrian Naval League, were sufficient for Montecuccoli to obtain the necessary funds he needed from the Austrian and Hungarian delegations in December 1910. By this time, some of the dreadnought battleships in his plan, Viribus Unitis and Tegetthoff, had already been laid down, effectively forcing the hand of the remaining members of the Austro-Hungarian government who opposed Montecuccoli's project.[26][27][13] The final version of Montecuccoli's proposal included a slight modification, with the build range for the ships expanding to 1916, and the final cost being brought down to 312.4 million Kronen. Despite heated debate among the deputies, including an attempt to kill the proposal outright and initiate talks with Italy to end the growing arms race between Austria-Hungary and its nominal ally, the vast majority of both the Austrian and Hungarian delegations supported Montecuccoli's plan to expand the navy.[26]

At a meeting before Austria-Hungary's common Ministerial Council on 5 January 1911, Montecuccoli justified the construction of the Novara-class cruisers by arguing that a class of light or scout cruisers were necessary for operations in the Adriatic Sea, and that their design would enable them to operate in the Mediterranean Sea as well if required. The final price for the ships of the Novara class, tentatively labeled "Cruiser G", "Cruiser H", and "Cruiser J", was to be 30 million Kronen, or 10 million per ship.[lower-alpha 4] By February, the final political hurdles had been cleared and the contract for the first cruiser of the class, "Cruiser G", was awarded to Cantiere Navale Triestino in Monfalcone. In April 1911, the contracts for "Cruiser H" and "Cruiser J" were awarded to Ganz-Danubius in Fiume.[28]

Design

The Novara-class cruisers were initially designed after the cruiser Admiral Spaun,[29] and while despite being a different class of its own, both contemporary and modern publications occasionally link all four ships together as members of the same class.[30][31][32][33][lower-alpha 1] The Novara-class cruisers were based on the premise that the theater of operations they would operate in would be largely confined to the Adriatic Sea. Montecuccoli believed that should Austria-Hungary be drawn into a larger naval conflict encompassing the Mediterranean, the Novara class would still be capable of fulfilling their roles successfully and that a class of battlecruisers was not necessary for such a scenario.[34]

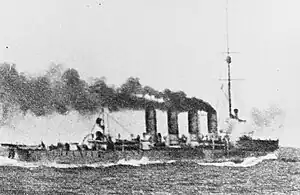

The Novara-class ships had an overall length of 130.64 meters (428 ft 7 in), with a beam of 12.79 meters (42 ft 0 in) and a mean draft of 4.6 meters (15 ft 1 in) at deep load. They were designed to displace 3,500 tonnes (3,400 long tons; 3,900 short tons) at normal load, but at full combat load they displaced 4,017 tonnes (3,954 long tons; 4,428 short tons). The propulsion systems of each ship consisted of two sets of steam turbines driving two propeller shafts. These turbines differed among the ships. Saida was equipped with two Melms-Pfenniger turbines, while Helgoland and Novara each had two AEG-Curtis turbines. These turbines were designed to provide 25,600 shaft horsepower (19,100 kW) and were powered by 16 Yarrow water-tube boilers, giving the Novara-class ships a top speed of 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph). Each ship also carried 710 metric tons (700 long tons) of coal that gave them a range of approximately 1,600 nautical miles (3,000 km; 1,800 mi) at 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph), and were manned by a crew of 340 officers and men.[35][2]

The Novaras were armed with a main battery of nine 50-caliber 10 cm (3.9 in) guns in single pedestal mounts. Three were placed forward on the forecastle of each ship, four were located amidships, two on either side, and two were side by side on the quarterdeck. Each ship also possessed a 47 mm (1.9 in) SFK L/44 gun. A Škoda 7 cm (2.8 in)/50 K10 anti-aircraft gun and six 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes in twin mounts were added to the Novara class in 1917. The guns of the Novara class were of a smaller caliber than many other cruisers of the era,[36] which led to plans to remove the guns on the forecastle and quarterdeck of each ship and replace them with a pair of 15-centimeter (5.9 in) guns fore and aft, but these modifications were not able to take place before the war ended.[35][2]

The Novara class was protected at the waterline with an armored belt which measured 60 mm (2.4 in) thick amidships. The guns had 40 mm (1.6 in) thick shields, while the thickness of the deck for each ship was 20 mm (0.79 in). The armor protecting each conning tower was 60 mm (2.4 in).[35][2]

Ships

| Name | Namesake | Builder | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saida | Bombardment of Saida | Cantiere Navale Triestino, Monfalcone | 9 September 1911 | 26 October 1912 | 1 August 1914 | Ceded to Italy, 19 September 1920 and renamed Venezia. Decommissioned on 11 March 1937 and scrapped. |

| Helgoland | Battle of Helgoland | Ganz-Danubius, Fiume | 28 October 1911 | 23 November 1912 | 5 September 1914 | Ceded to Italy, 19 September 1920 and renamed Brindisi. Decommissioned on 11 March 1937 and scrapped. |

| Novara | Battle of Novara | 9 December 1912 | 15 February 1913 | 10 January 1915 | Ceded to France in 1920 and renamed Thionville. Decommissioned on 1 May 1932 and converted into a barracks ship in Toulon. Scrapped in 1941. |

Construction

The first ship of the "Cruiser G", was formally laid down by Cantiere Navale Triestino at Monfalcone on 9 September 1911 after months of fiscal and political uncertainty as the ships' funding were tied to the same budget which authorized the Tegetthoff-class battleships. One month later "Cruiser H" was laid down by Ganz-Danubis in Fiume on 28 October 1911. The final ship of the class, "Cruiser J", was laid down in Fiume on 9 December 1912.[2][37]

"Cruiser G" was formally named Saida and launched from Monfalcone on 26 October 1912. She was named after the Austrian bombardment of the port city during the Oriental Crisis of 1840. Helgoland followed on 23 November 1912, being named after the Battle of Helgoland during the Second Schleswig War. Novara, named after the decisive Austrian victory at the Battle of Novara during the First Italian War of Independence was constructed in just over two months, being launched in Fiume on 15 February 1913.[2]

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo triggered a chain of events which led to the July Crisis and Austria-Hungary's subsequent declaration of war on Serbia on 28 July. Events unfolded rapidly in the ensuing days. On 30 July 1914 Russia declared full mobilization in response to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia. Austria-Hungary declared full mobilization the next day. On 1 August both Germany and France ordered full mobilization and Germany declared war on Russia in support of Austria-Hungary. While relations between Austria-Hungary and Italy had improved greatly in the two years following the 1912 renewal of the Triple Alliance,[38] increased Austro-Hungarian naval spending, political disputes over influence in Albania, and Italian concerns over the potential annexation of land in the Kingdom of Montenegro caused the relationship between the two allies to falter in the months leading up to the war.[39]

Italy's 1 August declaration of neutrality in the war dashed Austro-Hungarian hopes to use their larger ships, including the Novara class in major combat operations in the Mediterranean, as the navy had been relying upon coal stored in Italian ports to operate in conjunction with the Regia Marina. By 4 August Germany had already occupied Luxembourg and invaded Belgium after declaring war on France, and the United Kingdom had declared war on Germany in support of Belgian neutrality.[40] In response to these events, the Austro-Hungarian Navy decided to suspend any outstanding orders or construction projects on new warships, returning the monetary savings back to the Ministry of Finance for use in the war, which at the time was expected to be over in a matter of months.[41][42] When the war began, Saida was just days away from commissioning.[2] As a result, the Novara-class ships as well as the battleship Szent István were all allowed to continue their construction and fitting-out, though the final commissioning of both Szent István and Novara were delayed by the outbreak of the war.[41]

Service history

Saida was the first ship in the class to be commissioned into the Austro-Hungarian Navy on 1 August 1914, just four days after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.[2] Saida was immediately given a lead role,[43] being designated the flotilla leader of the First Torpedo Flotilla under Captain Heinrich Seitz.[44] The First Torpedo Flotilla included the six Tátra-class destroyers, six Huszár-class destroyers, 10–18 torpedo boats, and the depot ships Gäa and Steamer IV.[43][44] In her first mission, Saida led the First Torpedo Flotilla to the Austro-Hungarian naval base at Sebenico in August 1914.[43] Helgoland was commissioned on 5 September 1914,[2] and was also assigned to the First Torpedo Flotilla in Sebenico.

Following France and Britain's declarations of war on Austria-Hungary on 11 and 12 August respectively, the French Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère was issued orders to close off Austro-Hungarian shipping at the entrance to the Adriatic Sea and to engage any Austro-Hungarian ships his Anglo-French fleet came across. Lapeyrère chose to attack the Austro-Hungarian ships blockading Montenegro. The ensuing Battle of Antivari ended Austria-Hungary's blockade, and effectively placed the Strait of Otranto firmly in the hands of Britain and France.[45][46]

The two Novara-class ships in service at the time had been commissioned too late to participate in Austria-Hungary's naval maneuvers in support of the battlecruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau. After the Battle of Antivari and the breakout of Goeben and Breslau from Messina, the Austro-Hungarian Navy saw very little action, with many of its ships spending much of their time in port. The navy's general inactivity was partly caused by a fear of mines in the Adriatic.[47] Other factors contributed to the lack of naval activity in the first year of the war. Admiral Anton Haus was fearful that direct confrontation with the French Navy, even if it should be successful, would weaken the Austro-Hungarian Navy to the point that Italy would have a free hand in the Adriatic.[48] This concern was so great to Haus that he wrote in September 1914, "So long as the possibility exists that Italy will declare war against us, I consider it my first duty to keep our fleet intact."[49] Haus' decision to keep his fleet in port earned sharp criticism from the Austro-Hungarian Army, the German Navy, and the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry,[50] but it also led to a far greater number of Allied naval forces being devoted to the Mediterranean and the Strait of Otranto. These could have been used elsewhere, such as against the Ottoman Empire during the Gallipoli Campaign.[51] Throughout the rest of 1914, the Novara class were among the most active ships in the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Despite most of the navy remaining in port after August 1914, Helgoland did participate in a sortie to the island of Lissa on 3 November 1914 after receiving reports of French warships in the area, but the French departed from the vicinity before Helgoland arrived at the island.[52]

January–May 1915

By the time Novara was commissioned into the navy on 10 January 1915, Haus had adopted a cautious strategy to preserve his fleet, as Austria-Hungary was drastically outnumbered by the Anglo-French fleets in the Mediterranean, and the attitude of Austria-Hungary's erstwhile ally Italy remained unknown. Haus decided the best course of action would be to act as a fleet in being, which would tie down Allied naval forces, while torpedo boats, mines, and raids with fast cruisers like those of the Novara class could be used to reduce the numerical superiority of the enemy fleets before a decisive battle could be fought.[53]

Indeed, after the beginning of the Allied Dardanelles Campaign against the Ottoman Empire in March 1915, Germany began to pressure Austria-Hungary to assist the Ottomans. Haus considered sending Novara under the command of Miklós Horthy with a cargo of munitions to a friendly Ottoman port, but ultimately decided the operation was too risky for what would have been a minimal gain, as the ship would not have been able to carry a particularly large cargo.[33] Instead, the ships of the Novara class continued operations in the Adriatic. On 2 May, Novara towed the German U-boat UB-8 from Pola out of the Adriatic Sea. They evaded French patrols until 6 May, when the Austro-Hungarian ships were spotted by a French vessel off Cephalonia. Novara cut the tow and sped north, while U-8 submerged and evaded the French patrol.[54]

Bombardment of Ancona

After failed negotiations with Germany and Austria-Hungary over Italy joining the war as a member of the Central Powers, the Italians negotiated with the Triple Entente for Italy's eventual entry into the war on their side in the Treaty of London, signed on 26 April 1915.[55] On 4 May Italy formally renounced her alliance to Germany and Austria-Hungary, giving the Austro-Hungarians advanced warning that Italy was preparing to go to war against them. On 20 May, Emperor Franz Joseph I gave the Austro-Hungarian Navy authorization to attack Italian ships convoying troops in the Adriatic or sending supplies to Montenegro. Haus meanwhile made preparations for his fleet to sortie out into the Adriatic in a massive strike against the Italians the moment war was declared. On 23 May 1915, between two and four hours after the Italian declaration of war reached the main Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola,[lower-alpha 5] the Austro-Hungarian fleet, including the three ships of the Novara class, departed to bombard the Italian coast.[47][56]

During the Austro-Hungarian attacks along the Italian coastline, Novara, along with a destroyer and two torpedo boats, bombarded Porto Corsini near Ravenna. Defensive fire from Italian coastal guns killed six men aboard Novara, while leaving the cruiser relatively undamaged.[57] Meanwhile, Helgoland and two destroyers engaged and sank the Italian destroyer Turbine.[58] Saida and Helgoland, along with the cruisers Admiral Spaun and Szigetvár and nine destroyers, also provided a screen against a possible Italian counterattack, which did not materialize.[57]

The Austro-Hungarian fleet would later move on to bombard the coast of Montenegro, without opposition; by the time Italian ships arrived on the scene, the Austro-Hungarians were safely back in port.[59] The objective of the bombardment of Italy's coastline was to delay the Italian Army from deploying its forces along the border with Austria-Hungary by destroying critical transportation systems,[56] and the surprise attack on Ancona and the Italian Adriatic coast succeeded in delaying the Italian deployment to the Alps for two weeks. This delay gave Austria-Hungary valuable time to strengthen its Italian border and re-deploy some of its troops from the Eastern and Balkan fronts.[60] The bombardment and sinking of several Italian ships also delivered a severe blow to Italian military and public morale.[61]

June–December 1915

Following Italy's entry into the war in May 1915, the Novara-class ships would be regularly used throughout the rest of the year against the Italians in the Adriatic. Saida's first experiences in combat came on 28 July and again 17 August 1915 when she, Helgoland, and four destroyers bombarded Italian forces on the island of Pelagosa which had recently been occupied by the Italians, though planned Austro-Hungarian landings on the island were canceled after it became apparent that the Italian defenses were too strong.[62][63] In late 1915, the Austro-Hungarian Navy began a series of raids against the merchant ships supplying Allied forces in Serbia and Montenegro, with the Novara-class ships serving in a key capacity in these attacks. On the night of 22 November 1915, Saida, Helgoland, and the First Torpedo Division raided the Albanian coast and sank a pair of Italian transports carrying flour.[64] To facilitate further raids against Italian shipping, Helgoland, Novara, six Tátra-class destroyers, six 250t-class T-group torpedo boats and an oiler were transferred to Cattaro on 29 November.[64] On 5 December, Novara, four destroyers, and three torpedo boats made another attack on Italian shipping lanes, sinking three transport ships and numerous fishing boats. While conducting a raid on Shëngjin, they sank five steam ships and five sailing vessels, with one of the steam ships exploding due to munitions on board the vessel.[65] During this attack, the Austro-Hungarian ships spotted the French submarine Fresnel, which had run aground off the mouth of the Bojana river. Novara and the other Austro-Hungarian ships took the French crew captive and destroyed the submarine.[64] Helgoland and five destroyers, participated in another of these raids on the night of 28 December 1915. During this raid, Helgoland rammed and sank the French submarine Monge between Brindisi and the Albanian port of Durazzo, before attacking shipping in Durazzo the following morning.[31] After sinking several ships in the port, two of the Austro-Hungarian destroyers accompanying Helgoland struck mines and one sank. In response to these setbacks, Novara, Admiral Spaun, and the old coastal defense ship Budapest were mobilized to support Helgoland and the Austro-Hungarian destroyers. Helgoland was unscathed in the operation and managed to evade the Allied pursuit when darkness fell, rendezvousing with the reinforcements sent out to escort her back to Cattaro.[66][67]

1916

The Novara-class cruisers saw considerable success in the Adriatic throughout 1916. Despite Italian reports of the sinking of Helgoland by the French submarine Foucault on 13 January 1916, none of the ships of the Novara class would be sunk during the war.[68] Indeed, on 29 January 1916 Novara and two destroyers began another raid, this time on the port of Durazzo. While en route, the two destroyers collided with one another and had to return to port for repairs, leaving just Novara to conduct the attack. Upon reaching the target, she encountered the Italian protected cruiser Puglia and a French destroyer. After a short engagement, Novara broke off the attack and returned to port, since the element of surprise had been lost.[69]

On the night of 31 May 1916, Helgoland again led a raid with two destroyers and three torpedo boats on the drifters blockading the Strait of Otranto. These drifters were meant to prevent German and Austro-Hungarian submarines from trying to exit the Adriatic Sea. The attack led to the sinking of one drifter.[66] In mid-1916, Captain (German: Linienschiffskapitän) Miklós Horthy planned an attack on the Otranto Barrage with Novara, the ship he commanded at the time. On 9 July, he launched his attack. During the engagement, Novara sank a pair of drifters, damaged two more, and captured nine British sailors.[67] Chronic problems with Saida's turbines did not allow her to see as much action as her sister ships, and prevented her from being used for much of the war. This left Helgoland and Novara to shoulder most of the burden of the naval war in the Adriatic.[70] Despite Saida's mechanical issues, throughout most of the war the Novara-class ships served as the "real capital ships of the Adriatic",[71] as many of the larger ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, such as the Tegetthoff-class battleships, remained at port in Pola between May 1915 and June 1918.[50][47]

1917

In February 1917, captain Miklós Horthy planned a major raid on the drifters of the Otranto Barrage with all three ships of the Novara class participating in the attack. The three cruisers were modified to resemble destroyers, and were thoroughly overhauled in preparation for the attack. Their boilers and turbines were cleaned to ensure the highest efficiency, and an anti-aircraft gun was installed on each ship.[70] While the preparations were being made in late April and early May, destroyers made several sweeps down to the coast of Albania to ascertain Allied defenses, and the Austro-Hungarian ships found none. On 13 May, Rear Admiral (German: Konteradmiral) Alexander Hansa issued the order to begin the operation the following morning.[72] The ships were to attack separately while two accompanying destroyers, Balaton and Csepel, made a diversionary attack on the drifters near the Albanian coast.[73] On the night of 14 May, the ships departed port and managed to pass through the line of drifters in the darkness without being identified. As the sounds from the diversionary attack were heard, the drifters released their nets and began to head towards the Strait of Otranto.[74] Between 3:30 am and 03:45 am on 15 May, the Novara-class cruisers opened fire on 47 drifters,[73] though Saida stopped her engines and drifted toward the patrol vessels for about 30 minutes to conceal her position. The attack led to the sinking of fourteen drifters and four more were damaged before the Austro-Hungarians broke off the attack and withdrew. Saida attacked the Allied ships at 4:20 am, setting three drifters on fire, before stopping to pick up nineteen survivors.[75][76][77]

The first contact with Allied warships made by the Austro-Hungarian ships were by a group of four French destroyers led by a small Italian scout cruiser, Carlo Mirabello, but the heavier guns of the Austro-Hungarian ships dissuaded the Allied commander, Admiral Alfredo Acton, from pressing an attack.[78] They were intercepted shortly afterward by a stronger group of two British protected cruisers, Bristol and Dartmouth, escorted by four Italian destroyers. Dartmouth opened fire with her 6-inch (152 mm) guns at a range of 10,600 yards (9,700 m) and Horthy ordered his ships to lay a smoke screen several minutes later. Horthy called for reinforcements that came in the form of the armored cruiser Sankt Georg, which sortied with two destroyers and four torpedo boats.[79] The heavy smoke nearly caused the three Austrian cruisers to collide, but it shrouded them from the fire from the British ships as they closed range.[80] When they emerged, the Austro-Hungarian ships were only about 4,900 yards (4,500 m) from the British, a range much more suitable for the smaller Austrian guns.[81]

The three cruisers were gradually drawing away from their pursuers when Novara, leading the Austro-Hungarian fleet, was hit several times. Novara's boilers were disabled, leaving her dead in the water, while her executive officer had been killed and Horthy himself wounded.[80] Saida was preparing to take Novara under tow when several Italian destroyers attacked in succession. The weight of fire from the three cruisers prevented the Italians from closing to torpedo range, and they scored no hits. With covering fire being provided by Sankt Georg, Saida took Novara under tow for the voyage back to port.[82] The four cruisers assembled in line-ahead formation, with Sankt Georg the last vessel in the line, to cover the other three ships. Later in the afternoon, the old coastal defense ship Budapest and three more torpedo boats joined the ships to strengthen the escort.[83] During the battle, Helgoland under the command of Erich von Heyssler, fired 1,052 shells from her guns. Heyssler received the Order of Leopold with crossed swords in recognition of his leadership during the battle.[84] By 6:40 pm all three Novara-class cruisers were back at Cattaro, and after a week of repairs Novara was once again ready for action.[80]

Following the Battle of the Strait of Otranto, the Austro-Hungarian Navy attempted to follow up with similar raids. Helgoland and six destroyers tried to duplicate the attack with another raid on the night of 18 October, but they were spotted by Italian aircraft and turned back in the face of substantial Allied reinforcements.[85]

1918

By early 1918, the long periods of inactivity had begun to wear on the crews of several Austro-Hungarian ships at Cattaro, primarily those of ships which saw little combat. On 1 February, the Cattaro Mutiny broke out, starting aboard Sankt Georg. The mutineers rapidly gained control of the cruiser Kaiser Karl VI and most of the other major warships in the harbor.[86] The crews of Novara and Helgoland resisted the mutiny,[87] with the latter preparing their ship's torpedoes but Sankt Georg's gunners aimed their 24 cm (9.4 in) guns at Helgoland, forcing them to back down. Novara's commander, Johannes, Prinz von Liechtenstein, initially refused to allow a rebel party to board his vessel, but after Kaiser Karl VI trained her guns on Novara, he relented and let the crew fly a red flag in support of the mutiny. Liechtenstein and Erich von Heyssler, the commander of Helgoland, discussed overnight how to extricate their vessels, their crews having abstained from actively supporting the rebels.[88]

The following day, many of the mutinous ships abandoned the effort and rejoined loyalist forces in the inner harbor after shore batteries loyal to the Austro-Hungarian government opened fire on the rebel guard ship Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf. Liechtenstein tore down the red flag before ordering his ship to escape into the inner harbor; they were joined by the other scout cruisers and most of the torpedo boats, followed by several of the other larger vessels. There, they were protected by shore batteries that opposed the mutiny. By late in the day, only the men aboard Sankt Georg and a handful of destroyers and torpedo boats remained in rebellion. The next morning, the Erzherzog Karl-class battleships arrived from Pola and put down the uprising.[89][90]

After the Cattaro Mutiny, Admiral Maximilian Njegovan was fired as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, though at Njegovan's request it was announced that he was retiring.[11] Miklós Horthy, who had since been promoted to commander of the battleship Prinz Eugen, was promoted to rear admiral and named Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet. Horthy's promotion was met with support among many members of the naval officer corps, who believed he would use Austria-Hungary's navy to engage the enemy. Horthy's appointment posed difficulties. His relatively young age alienated many of the senior officers, and Austria-Hungary's naval traditions included an unspoken rule that no officer could serve at sea under someone of inferior seniority. This meant that the heads of the First and Second Battle Squadrons, as well as the Cruiser Flotilla, all had to go into early retirement.[91]

Otranto Raid

Horthy was determined to use the fleet to attack the Otranto Barrage, and he planned to repeat his successful raid on the blockade in May 1917.[92] Horthy envisioned a massive attack on the Allied forces with his four Tegetthoff-class ships providing the largest component of the assault. They would be accompanied by the three ships of the Erzherzog Karl-class pre-dreadnoughts, all three ships of the Novara class, the cruiser Admiral Spaun, four Tátra-class destroyers, and four torpedo boats. Submarines and aircraft would also be employed in the operation to hunt down enemy ships on the flanks of the fleet.[93][94][95]

On 8 June 1918 Horthy took his flagship, Viribus Unitis, and Prinz Eugen south with the lead elements of his fleet.[92] On the evening of 9 June, Szent István and Tegetthoff followed along with their own escort ships. Horthy's plan called for Novara and Helgoland to engage the Barrage with the support of the Tátra-class destroyers. Meanwhile, Admiral Spaun and Saida would be escorted by the fleet's four torpedo boats to Otranto to bombard Italian air and naval stations.[96] The German and Austro-Hungarian submarines would be sent to Valona and Brindisi to ambush Italian, French, British, and American warships that sailed out to engage the Austro-Hungarian fleet, while seaplanes from Cattaro would provide air support and screen the ships' advance. The battleships, and in particular the Tegetthoffs, would use their firepower to destroy the Barrage and engage any Allied warships they ran across. Horthy hoped that the inclusion of these ships would prove to be critical in securing a decisive victory.[94]

En route to the harbor at Islana, north of Ragusa, to rendezvous with the battleships Viribus Unitis and Prinz Eugen for the coordinated attack on the Otranto Barrage, Szent István and Tegetthoff attempted to make maximum speed in order to catch up to the rest of the fleet. In doing so, Szent István's turbines started to overheat and speed had to be reduced. When an attempt was made to raise more steam in order to increase the ship's speed, Szent István produced an excess of smoke. At about 3:15 am on 10 June,[lower-alpha 6] two Italian MAS boats, MAS 15 and MAS 21, spotted the smoke from the Austrian ships while returning from an uneventful patrol off the Dalmatian coast. Both boats successfully penetrated the escort screen and split to engage each of the dreadnoughts. MAS 15 fired her two torpedoes successfully at 3:25 am at Szent István. Szent István was hit by two 45-centimeter (18 in) torpedoes abreast her boiler rooms. Tegetthoff attempted to take Szent István in tow, which failed.[97] At 6:12 am, with the pumps unequal to the task, Szent István capsized off Premuda.

Fearing further attacks by torpedo boats or destroyers from the Italian navy, and possible Allied dreadnoughts responding to the scene, Horthy believed the element of surprise had been lost and called off the attack, forcing the Novara-class ships back to port. In reality, the Italian torpedo boats had been on a routine patrol, and Horthy's plan had not been betrayed to the Italians as he had feared. The Italians did not even discover that the Austrian dreadnoughts had departed Pola until 10 June when aerial reconnaissance photos revealed that they were no longer there.[98] Nevertheless, the loss of Szent István and the blow to morale it had on the navy forced Horthy to cancel his plans to assault the Otranto Barrage. The Austro-Hungarian ships returned to their bases where they would remain for the rest of the war.[99][100]

End of the war

By October 1918 it had become clear that Austria-Hungary was facing defeat in the war. With various attempts to quell nationalist sentiments failing, Emperor Karl I decided to sever Austria-Hungary's alliance with Germany and appeal to the Allied Powers in an attempt to preserve the empire from complete collapse. On 26 October Austria-Hungary informed Germany that their alliance was over. At the same time, the Austro-Hungarian Navy was in the process of tearing itself apart along ethnic and nationalist lines. Horthy was informed on the morning of 28 October that an armistice was imminent, and used this news to maintain order and prevent a mutiny among the fleet. While a mutiny was spared, tensions remained high and morale was at an all-time low. The situation was so stressful for members of the navy that the captain of Prinz Eugen, Alexander Milosevic, committed suicide in his quarters aboard the battleship.[101]

On 29 October the National Council in Zagreb announced Croatia's dynastic ties to Hungary had come to a formal conclusion. The National Council also called for Croatia and Dalmatia to be unified, with Slovene and Bosnian organizations pledging their loyalty to the newly formed government. This new provisional government, while throwing off Hungarian rule, had not yet declared independence from Austria-Hungary. Thus Emperor Karl I's government in Vienna asked the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs for help maintaining the fleet stationed at Pola and keeping order among the navy. The National Council refused to assist unless the Austro-Hungarian Navy was first placed under its command.[102] Emperor Karl I, still attempting to save the Empire from collapse, agreed to the transfer, provided that the other "nations" which made up Austria-Hungary would be able to claim their fair share of the value of the fleet at a later time.[103] All sailors not of Slovene, Croatian, Bosnian, or Serbian background were placed on leave for the time being, while the officers were given the choice of joining the new navy or retiring.[103][104]

The Austro-Hungarian government thus decided to hand over the bulk of its fleet to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs without a shot being fired. This was considered preferential to handing the fleet to the Allies, as the new state had declared its neutrality. Furthermore, the newly formed state had also not yet publicly dethroned Emperor Karl I, keeping the possibility of reforming the Empire into a triple monarchy alive. The transfer to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs began on the morning of 31 October, with Horthy meeting representatives from the South Slav nationalities aboard his flagship, Viribus Unitis in Pola. After "short and cool" negotiations, the arrangements were settled and the handover was completed that afternoon. The Austro-Hungarian Naval Ensign was struck from Viribus Unitis, and was followed by the remaining ships in the harbor.[105] Control over the battleship, and the head of the newly-established navy for the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, fell to Captain Janko Vuković, who was raised to the rank of admiral and took over Horthy's old responsibilities as Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet.[106][104][107]

Despite the transfer, on 3 November 1918 the Austro-Hungarian government signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti with Italy, ending the fighting along the Italian Front.[108] The Armistice of Villa Giusti refused to recognize the transfer of Austria-Hungary's warships to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. As a result, on 4 November 1918, Italian ships sailed into the ports of Trieste, Pola, and Fiume. On 5 November, Italian troops occupied the naval installations at Pola. While the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs attempted to hold onto their ships, they lacked the men and officers to do so as most sailors who were not South Slavs had already gone home. The National Council did not order any men to resist the Italians, but they also condemned Italy's actions as illegitimate. On 9 November, Italian, British, and French ships sailed into Cattaro and seized the remaining Austro-Hungarian ships which had been turned over to the National Council. At a conference at Corfu, the Allied Powers agreed the transfer of Austria-Hungary's Navy to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs could not be accepted, despite sympathy from the United Kingdom. Faced with the prospect of being given an ultimatum to hand over the former Austro-Hungarian warships, the National Council agreed to hand over all the ships transferred to them by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to include the three ships of the Novara class, beginning on 10 November 1918.[109]

Post-war

It would not be until 1920 when the final distribution of the ships was settled among the Allied powers under the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. France was ceded Novara, while Italy took over Helgoland and Saida.[110] Unlike the larger battleships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, the Novara-class cruisers were not scrapped shortly after the war, as their performance in the Adriatic had impressed the French and Italians.[111] The Novara-class cruisers were the largest ships of Austro-Hungarian Navy to serve under the flag of another nation after the war, as they were given to the victorious Allied powers.[3]

Saida was formally handed over to Italy on 19 September 1920 and later commissioned as Venezia on 5 July 1921 after her anti-aircraft gun was replaced with a 37 mm (1.5 in) anti-aircraft gun of Italian manufacture. Apart from that modification, the ship served in her original configuration. From 1930, she served as a barracks ship, first at Genoa and then in La Spezia.[112] In September 1935, Venezia was drydocked at La Spezia in preparation of being laid up before being scrapped.[113] The ship was sold for scrapping 11 March 1937 and was subsequently broken up.[2]

Helgoland was also ceded to Italy on 19 September 1920. She was subsequently renamed Brindisi and anchored at Bizerte, Tunisia, when the transfer was made, the ship was rated as a scout cruiser (Italian: esploratore) by Italy, and reached La Spezia on 26 October where she was assigned to the Scouting Group (Italian: Gruppo Esploratori). The ship was modified to suit the Italians at La Spezia from 6 April to 16 June 1921 before she entered service. She became the flagship of Rear Admiral Massimiliano Lovatelli, commander of the Light Squadron, upon recommissioning. Brindisi sailed for Istanbul on 3 July, visiting a number of ports in Italy, Greece, and Turkey en route. She relieved the armored cruiser San Giorgio as flagship of the Eastern Squadron upon her arrival on 16 July. The ship was replaced as flagship on 6 October and remained assigned to the Eastern Squadron until she returned to Italy on 7 January 1924.[35]

Brindisi hosted King Victor Emmanuel III aboard during the ceremonies that transferred Fiume to Italian control in accordance with the Treaty of Rome in February–March 1924.[35] The ship was then transferred to Libya where she spent the next year. Brindisi returned to Italy in 1926 and was briefly assigned to the Scout Squadron on 1 April before she was placed in reserve on 26 July. The ship was reactivated on 1 June 1927 when she was assigned as the flagship of the 1st Destroyer Squadron under the command of Rear Admiral Enrico Cuturi. Six months later, she was relieved as flagship and was transferred to the Special Squadron where she became flagship of Rear Admiral Antonio Foschini on 6 June 1928. Between May–June 1929, Brindisi made a cruise in the Eastern Mediterranean where she visited ports in Greece and the Dodecanese Islands. Rear Admiral Salvatore Denti relieved Foschini on 15 October and the ship was disarmed on 26 November. Following her disarmament, Brindisi was used as a depot ship at Ancona, Pula, and Trieste until she was stricken from the Navy List on 11 March 1937 and sold for scrapping alongside Venezia.[114]

While being handed over to the French Navy, Novara sank at Brindisi on 29 January 1920.[115] She was refloated in early April 1920.[116] The ship was renamed Thionville and incorporated into the French fleet after repairs. Thionville was assigned to the torpedo school for use as a training ship, a role she filled until 1 May 1932.[117] The ship was then disarmed and converted into a barracks ship based in Toulon. She remained there until 1941, when she was broken up for scrap.[2]

Notes

- The similarities between the Novara class and the cruiser Admiral Spaun has led to some confusion whereby the three Novara-class cruisers have occasionally been identified as members of a class of four ships, with Admiral Spaun as the lead ship of the class. Most sources draw distinctions between the Novara class and Admiral Spaun however, and recognize them as independent from one another.

- The full name of the Austrian Naval League was "The Association for Advancement of Austrian Shipping: The Austrian Fleet's Association"

- This table includes battleships which would later on be relegated to secondary roles, such as the Monarch-class coastal defense ships

- The Austro-Hungarian Navy followed the traditional German custom of not naming a new ship until it was formally launched. As a result, the Navy only referred to the three Novara-class cruisers during the planning and construction phases of their development as "Cruiser G", "Cruiser H", and "Cruiser J". Upon their launching, they were formally named Saida, Helgoland, and Novara respectively.

- Halpern states that it was four hours after the news of Italy's declaration of war reached Pola until the fleet set sail while Sokol claims that the fleet departed two hours after the declaration reached Admiral Haus.

- There is some debate on what was the exact time when the attack took place. Sieche states that the time was 3:15 am when Szent István was hit while Sokol claims that the time was 3:30 am.

Citations

- Gill 1922, p. 1988.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 336.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 363.

- Vego 1996, p. 35.

- Vego 1996, p. 19.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 170.

- Vego 1996, p. 38.

- Vego 1996, pp. 38–39.

- Sokol 1968, pp. 68–69.

- Sokol 1968, p. 68.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 144.

- Vego 1996, p. 43.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 194.

- Sokol 1968, p. 158.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 128, 173.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 128.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 173.

- Vego 1996, p. 36.

- Vego 1996, p. 39.

- Kiszling 1934, p. 739.

- Vego 1996, pp. 39–41.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 183.

- Vego 1996, pp. 62, 69.

- Vego 1996, p. 62.

- Vego 1996, p. 69.

- Vego 1996, p. 73.

- Sieche 1991, p. 115.

- Vego 1996, pp. 74, 82.

- Vego 1996, pp. 52–53.

- Henderson 1919, p. 353.

- Gill 1916, p. 307.

- Scheifley 1935, p. 58.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 266.

- Vego 1996, p. 74.

- Fraccaroli 1976, p. 317.

- Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 25.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 198–199.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 232–234.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 245–246.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 246.

- Sokol 1978, p. 185.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 269.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 257.

- Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 16.

- Koburger 2001, pp. 33, 35.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 251.

- Halpern 1994, p. 144.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 260.

- Halpern 1987, p. 30.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 261.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 380–381.

- Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 35.

- Halpern 1994, p. 141.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 268.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 272.

- Sokol 1968, p. 107.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 274–275.

- Fraccaroli 1970, p. 66.

- Hore 2006, p. 180.

- Sokol 1968, p. 109.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 276.

- Halpern 1994, p. 150.

- Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 36.

- Halpern 1994, p. 154.

- Gill 1916, p. 308.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 7–8.

- Halpern 1994, p. 161.

- Gill 1916, pp. 307, 661.

- Halpern 1994, p. 158.

- Halpern 2004, p. 44.

- Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 37.

- Koburger 2001, p. 72.

- Sokol 1968, p. 128.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 62–66.

- Halpern 2004, p. 64.

- Halpern 1994, pp. 162–163.

- Sokol 1968, pp. 128–129.

- Sokol 1968, p. 129.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 79–80.

- Sokol 1968, p. 130.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 63, 72, 74–75, 80–86.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 86–97.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 100–101.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 102–104.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 133–134.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 48–50.

- Koburger 2001, p. 96.

- Halpern 2004, p. 50.

- Halpern 2004, pp. 52–53.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 322.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 326.

- Koburger 2001, p. 104.

- Halpern 1987, p. 501.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 335.

- Sokol 1968, p. 134.

- Halpern 2004, p. 142.

- Sokol 1968, p. 135.

- Sieche 1991, p. 135.

- Sokol 1968, pp. 134–135.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 336.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 350–351.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 351–352.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 352.

- Sokol 1968, pp. 136–137, 139.

- Koburger 2001, p. 118.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 353–354.

- Halpern 1994, p. 177.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 329.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 357–359.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 359.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 357.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 264.

- Willmott 2009, p. 60.

- Fraccaroli 1976, pp. 317–18.

- "Imperial and Foreign News Items". The Times. No. 42321. London. 30 January 1920. col F, p. 11.

- "Imperial and Foreign News Items". The Times. No. 42376. London. 5 April 1920. col F, p. 7.

- Jordan & Moulin 2013, p. 167.

References

- Dickson, W. David; O'Hara, Vincent; Worth, Richard (2013). To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1612510828.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0105-7.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1976). "Question 14/76: Details of Italian Cruiser Brindisi". Warship International. International Naval Research Organization. XIII (4): 317–318. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Gill, C.C. (November–December 1916). Greenslade, J.W. (ed.). "Austrian Cruiser Torpedoed and Sunk by French Submarine in Adriatic Sea". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. 42 (6).

- Gill, C.C. (July 1922). Greenslade, J.W. (ed.). "Professional Notes". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. 48 (11).

- Greger, René (1976). Austro-Hungarian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0623-7.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1987). The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1914-1918. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870214489.

- Halpern, Paul (2004). "The Cattaro Mutiny, 1918". In Bell, Christopher M.; Elleman, Bruce A. (eds.). Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective. London: Frank Cass. pp. 45–65. ISBN 0-7146-5460-4.

- Henderson, W.H. (30 March 1919). "Four Months in the Adriatic". The Naval Review. The Naval Society. IV.

- Hore, Peter (2006). Battleships. London: Lorena Books. ISBN 978-0-7548-1407-8. OCLC 56458155.

- Jordan, John & Moulin, Jean (2013). French Cruisers: 1922–1956. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-133-5.

- Kiszling, Rudolf (September 1934). "Die Entwicklung der Oesterreichisch-Ungarischen Wehrmacht seit der Annexion Krise 1908". Berliner Montaschefte (in German). Berlin (9).

- Koburger, Charles (2001). The Central Powers in the Adriatic, 1914–1918: War in a Narrow Sea. Westport: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-313-00272-4.

- Scheifley, William (1935). Impressions of Postwar Europe. Wetzel Publishing.

- Sieche, Erwin (2002). Kreuzer und Kreuzerprojekte der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine 1889–1918 [Cruisers and Cruiser Projects of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1889–1918] (in German). Hamburg. ISBN 3-8132-0766-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sieche, Erwin F. (1991). "S.M.S. Szent István: Hungaria's Only and Ill-Fated Dreadnought". Warship International. International Warship Research Organization. XXVII (2): 112–146. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Sokol, Eugene (1978). "Austria-Hungary's Naval Building Projects, 1914–1918". Warship International. International Naval Research Organization. 3. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Sokol, Anthony (1968). The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 462208412.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867-1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-034-3.

- Vego, Milan N. (1996). Austro-Hungarian Naval Policy: 1904–14. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0714642093.

- Willmott, H. P. (2009). The Last Century of Sea Power (Volume 2, From Washington to Tokyo, 1922–1945). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253004093.

- Freivogel, Zvonimir (2017). Austro-Hungarian Cruisers in World War One. Zagreb: Despot Infinitus. ISBN 978-953-7892-85-2.

Further reading

- Sifferlinger, Nikolaus (2008). Rapidkreuzer Helgoland. Im Einsatz für Österreich-Ungarn und Italien [Scouting Cruiser Helgoland. In Service for Austria-Hungary and Italy] (in German). Wien, Graz: NW Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag. ISBN 978-3-70830-133-4.

External links

- Details and photos of Admiral Spaun (text in German)

- Details and photos of Saida, Helgoland and Novara (text in German)

- Post war distribution of Austro-Hungarian warships