Railroad chapel car

As Americans moved west aided by the railroads, some Christian religious denominations saw an opportunity to expand to those living in such areas. The Baptist, Episcopal and Roman Catholic faiths used specially fitted railroad cars called Chapel cars to provide religious services and information from the 1890s to the 1930s. The cars served as both a place for religious services as well as living quarters for the missionary pastors. The fronts of the cars were designed to act as "churches on wheels" with altars, pews, and in some cases, stained glass windows.

The concept of chapel car

William David Walker was appointed Episcopal Bishop of North Dakota in 1883 and was faced with overseeing an enormous territory with few settlers and the fact that Western towns often were born or died as a result of the fortunes of those living in them.[1][2] The discovery of gold or silver could mean that a town would spring up almost overnight as others sought to become part of the newly found riches; merchants established businesses to cater to those connected with the mining. Conversely, the news that the ore vein was spent meant people would move on to the next opportunity, merchants needed to close their doors due to lack of business, and the town was in danger of becoming deserted. With this volatile situation, if money could be donated to establish a church in a town, there was no guarantee there would continue to be enough people and donations to sustain it.[3]

After an 1889 tour of Siberia and visiting the chapel cars of the Trans-Siberian Railway,[4] Walker had the idea of building a railroad chapel car that could travel through his diocese to conduct services and other business of the church.[2] He thought that while most non-mobile churches would not survive if built, a traveling church car would be able to accomplish similar tasks and would be sustainable. Walker took his idea to those in the East with a plea for contributions to build this type of railroad car. The Episcopal Church was inspired by Walker's concept and held many fund-raising events for the chapel car throughout their Eastern dioceses. He also received a large donation for this purpose from Cornelius Vanderbilt, himself the president of the New York Central Railroad. When Walker had raised $3,000, he was ready to build his chapel car and ordered it from Chicago's Pullman Company, naming it The Church of the Advent—The Cathedral Car of North Dakota.[1][5][6]

Episcopal chapel cars

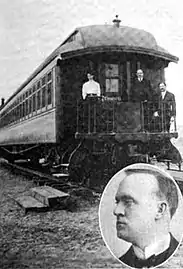

The Church of the Advent—The Cathedral Car of North Dakota

The car, measuring 60 feet in length, had two sections, one for worship services, complete with an organ, and the other for living quarters and an office for Walker. It was ready for transport to Fargo, North Dakota, on November 13, 1890. Walker hosted a number of Chicagoans who toured the car before it made its way to North Dakota.[7][1] Walker was able to travel his diocese by the local railroads' willingness to pull the chapel car without charge. He would notify locales in advance of his arrival, and the car would be pulled to a siding near the local railroad station, where he would then conduct services.[1]

When the car was retired from service in 1899, Walker and his successor, Bishop Edsell, had traveled 70,000 miles throughout North Dakota with it. The car was permanently based in Carrington, North Dakota, before being sold in 1901. St. Mary's Church in Guelph, North Dakota, received the baptismal font and lectern from the chapel car.[1]

Diocese of Northern Michigan chapel cars

Bishop Mott Williams, head of the diocese of Northern Michigan, faced the same problems as Bishop Walker regarding reaching communicants who were often far from a church. He did not have the same financial opportunities, so his choice was to purchase two retired rail coaches and have them converted into chapel cars, which served this diocese from 1891 to 1898.[2][6] When a fire destroyed most of the town of Ontonagon, Michigan in 1898, the town's churches were also lost. The Chapel Car of Northern Michigan provided a temporary home for services to all faiths whose churches had been destroyed.[6][8]

Baptist chapel cars

By 1891, the first of the American Baptist Publication Society chapel cars made its debut. Based on the research regarding children's attendance at Sunday schools and increasing church membership by Boston W. Smith, businessmen Charles L. Colby and Colgate Hoyt donated the funds to build and outfit the Society's first chapel car, Evangel, built by Barney & Smith.[9] Hoyt, whose brother, Wayland, was the pastor of the First Baptist Church of Minneapolis, was a vice-president and board member of many American railroads. While on a cross-country railroad trip, a discussion between the two brothers was the beginning of the Baptist chapel car project. Hoyt also organized other wealthy businessmen into what was known as the "Baptist Chapel Car Syndicate"; one of these members was oil magnate John D. Rockefeller.[2][6][10]

The Baptist chapel car fleet grew to a total of seven cars, all built by Barney & Smith during the years 1890 to 1913.[6] Thomas Edison, though not a member of the church, donated phonographs for all the chapel cars.[3]

Evangel

The Evangel was similar to the Episcopal The Church of the Advent—The Cathedral Car of North Dakota in size and in layout, with half of the car used as a chapel and the other half for living quarters. The car was dedicated May 23, 1891, at Cincinnati's Grand Central Depot and it made its way to St. Paul, Minnesota, where local church members provided linens, rugs, silver and dishes. The Baptist young peoples' societies raised money to have the car's windows screened, which sent it back to the shop for a time while they were fitted. The Estey company donated an organ.[2][6]

Boston Smith, who was initially aboard Evangel, had been provided with a letter from William Mellen, the general manager of the Northern Pacific Railway, which granted him and the chapel car free passage throughout the railroad's system. However, just as Smith was to set out on his first trip, railroad officials inquired whether the chapel car had been fitted with special wheels designed to prevent accidents. The railway's rules were that all special cars be fitted with them instead of the ordinary iron wheels used by other railroad cars. The Evangel was equipped with plain iron wheels but was allowed to travel as far as Livingston, Montana, before the wheels had to be changed.[2][6]

At Portland, Oregon in December 1891, Smith turned the car over to its first missionaries, the Wheelers. By 1892, the chapel car was called upon to serve the states of Minnesota and Wisconsin. In 1894, Evangel was brought to serve the southern United States. From 1901 until 1924, the chapel car traveled the rails of Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, Colorado and Nebraska before being retired to Rawlins, Wyoming, where the car was incorporated into the design of the local Baptist church by 1930.[2][6] The church, Chapel Car Bible Church, located at 12th and W. Maple Street, has started a restoration project in hopes of uncovering parts of the original train that have been hidden and highlighting the chapel car and its missionary history. The church is open for visitors to view the chapel car upon appointment.

Emmanuel

The car was being built during the financial panic of 1893. While Barney & Smith was able to build the Evangel at cost, it was now a public corporation and was struggling to stay solvent. The price quoted for the car did not include any of the interior necessities. Many items that went into the building of the Emmanuel were donations from corporations: brakes from Westinghouse Air Brake Company, various springs and wheels, along with flatware, blankets and a range for cooking were donated. Still, others were donated by the various Baptist organizations. The car's furnishings were a gift from the women of the First Baptist Churches of Oakland and San Francisco. The car, which was ten feet longer than the Evangel, was dedicated in Denver, Colorado, on May 24, 1893.[2]

The Wheelers, who were the first missionaries aboard the Evangel were also the first to travel with Emmanuel. In 1895, the chapel car was sent into the shop for repainting and repairs, making it necessary for the Wheelers to vacate it while the work was done. While making their way home to Minnesota, the train they were aboard was involved in a wreck and Mr. Wheeler was killed. As a memorial to him, a stained glass window was created and mounted in the door leading to the living quarters section of the car.[2]

The car traveled in the western and northwestern states and territories until 1938, where it sat on a spur in South Fork, Colorado. In 1942, a decision was reached to move the aging chapel car to a Baptist camp at Swan Lake, South Dakota, where it sat for thirteen years before being sold for scrap. The car was then used for storage by an engineering company. While there, a carpenter for the Prairie Village park saw the car and realized its potential to be restored. The Emmanuel was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and was fully restored by 1982.[2][11] Its permanent home is at Prairie Village.[2][12]

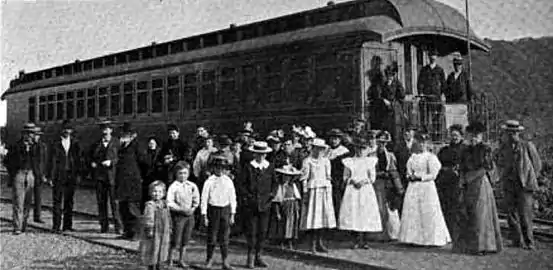

The Hermistons, who rode in Emmanuel for 41,000 miles.

The Hermistons, who rode in Emmanuel for 41,000 miles. A children's service aboard Emmanuel.

A children's service aboard Emmanuel. Chapel car Emmanuel in Santa Barbara, California.

Chapel car Emmanuel in Santa Barbara, California. Children after a service on the car.

Children after a service on the car.

Glad Tidings

A gift of businessman William Hills, the car was dedicated in Saratoga Springs, New York, on May 25, 1894. Hills placed one condition on his gift: that matching funds to build a fourth chapel car be raised before the end of the year. The first missionaries for the car, the Rusts, were newlyweds at the time of their assignment. Two of their five children were born on Glad Tidings. The car traveled in the midwestern states and territories served by the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad. In 1905, the Rusts left chapel car work and Glad Tidings was turned over to chapel car missionaries serving in Colorado, Wyoming and Arizona. Various restrictions, including those of World War I, kept the car in Douglas, Wyoming, for the years 1915 through 1919. Because it had been sidelined for a period of years, the car was sent for some needed maintenance in 1920 before being assigned to a new Arizona route.[2][6]

The chapel car continued its work in Arizona until 1926, when it was brought to its final destination of Flagstaff. There its wheels and trucks were removed, and it was placed on a foundation as the "Glad Tidings Baptist Church" until it was dismantled in the early 1930s.[2][6]

Chapel car Glad Tidings.

Chapel car Glad Tidings. Children's/Young people's meeting.

Children's/Young people's meeting. Railroad workers outside of the car.

Railroad workers outside of the car. Railroad workers inside the car for a service.

Railroad workers inside the car for a service.

Good Will

Dedicated in Saratoga Springs, New York, on June 1, 1895, the car was sent to serve the growing population of Texas and worked in cooperation with the Texas Baptist Convention. At the time of the 1900 Galveston hurricane, the missionaries were in the city, but the chapel car was in the Galveston Santa Fe Railroad shop for work. It was damaged but not destroyed by the storm as a result; the damage made it necessary to ask for special donations from Texas Baptist congregations to pay for the additional repairs. By 1905, its mission service area had been changed to routes in Missouri and Colorado, later continuing on to the west and Pacific northwest, where it continued to travel for another twenty years. In 1938, it was time to find the car a permanent foundation, and it was parked behind the hotel in Boyes Hot Springs, California. The car was discovered in the same place in 1998 and remains unrestored.

Messenger of Peace

Messenger of Peace was also known as the "Ladies' Car" because it was built with $100 donations from 75 Baptist women. Even though economic times were still difficult for the car's manufacturer, Barney & Smith, the company was able to provide this car at cost. It was dedicated on May 21, 1898, in Rochester, New York. In 1904, it went on display at the Palace of Transportation at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition where it received first prize for a railroad car exhibit.[13]

The chapel car traveled in the midwestern states until 1910, when it was sent to serve the YMCA for a year. During that time, it also traveled to Boston for a Protestant missionary exposition.[13] By 1913, it was on its way to the Pacific Northwest, where it worked in Washington state through two world wars. The car was retired in 1948 and was turned into a diner after being sold. It was discovered on private property being used for storage in 1997; ten years later, it was donated to the Northwest Railway Museum, where it was under restoration by master craftsman Kevin Palo until December 2012.[2][14][15][16][17]

Herald of Hope

This car, which was the last made of wood, was called "The Young Men's Car" because the young men of Detroit's Woodward Baptist Church had raised the first $1,000 of its costs. Dedicated in Detroit on May 27, 1900, it served the midwestern states. In 1911, it was reconditioned at the Barney & Smith factory at Dayton, Ohio, and in 1915, embarked on a new mission to West Virginia, serving there until its last missionary, William Newton, died in 1931. His wife, Fannie, refused to leave the chapel car, as she considered it her home. She remained there until 1935.[18][2]

After 1935, the fate of the chapel car was unknown until 1947, when a photograph was obtained of the car without wheels, which had been used as an office for an abandoned coal company in the Quinwood, West Virginia, an area where the Newtons had last served as missionaries.[2]

Children gathered around the chapel car after a service for them.

Children gathered around the chapel car after a service for them. Railroad workers who attended a meeting for them on the car.

Railroad workers who attended a meeting for them on the car.

Grace

This was the last of the Baptist chapel cars built and the only one that was constructed of steel. Donated by the Conaway family in memory of their daughter, Grace, it was also built by the Barney & Smith factory in 1915, at a cost of over five times the price paid for the first chapel car, Evangel. The car was dedicated in Los Angeles in 1915 and was on display at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco before beginning work in California. Grace also served in Nevada, Utah, Wyoming and Colorado before being placed on permanent display at the American Baptist Assembly at Green Lake, Wisconsin, in 1946.[2][6]

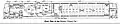

Floor plan of chapel car Grace.

Floor plan of chapel car Grace. Photo of the car's interior.

Photo of the car's interior. Photo of chapel car Grace.

Photo of chapel car Grace.

Roman Catholic chapel cars

Father Francis Kelley became the president of the newly formed Catholic Church Extension Society in 1905. Kelley visited the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition and toured the Baptist chapel car, Messenger of Peace. While there, he was impressed with what the chapel car was able to do for the Baptist faith. Since the mission of the Extension Society was to bring the Catholic faith to those in remote areas, he believed the use of chapel cars would be an effective way to accomplish this.[19][1][2][20]

In an article for Extension Magazine, he wrote, "If the Baptists can do it, why not the Catholics?", and asked for someone to donate a railroad car for this purpose.[2] From 1907 to 1915, three chapel cars were given to the Extension Society. Two of the cars were built by the Pullman Company while one was built by Dayton's Barney & Smith.[2][6][1]

St. Anthony

The first of these cars was St. Anthony, donated by Ambrose Petry and Richmond Dean, who was a Pullman Company vice-president. The car, originally built by Pullman in 1886, was refitted by Dean at the Pullman factory as a chapel car with a living area for its priests.[2][1][21] The 72-foot-long car was dedicated and blessed in 1907. It served in Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and also in the west and Pacific northwest. By 1909, it made its way to Oregon, where it was credited with creating more than 80 Catholic parishes. The car was taken from railroad service in 1919, when railroads no longer would handle wooden passenger cars.[19][6][2][1]

Photo of what appears to be the dedication of the chapel car St. Anthony. It appears to have been taken at the Pullman factory where it was refitted.

Photo of what appears to be the dedication of the chapel car St. Anthony. It appears to have been taken at the Pullman factory where it was refitted. Exterior of the St. Anthony chapel car.

Exterior of the St. Anthony chapel car. Interior of the St. Anthony chapel car.

Interior of the St. Anthony chapel car.

St. Peter

When Dayton businessman Peter Kuntz visited the St. Anthony chapel car, he asked the Extension Society why it did not build a fine chapel car instead of the wooden, refitted one. Kuntz then donated $25,000 to fund a Barney & Smith built steel chapel car in 1912 named St. Peter.[22] At the time it was built, it was one of the longest railroad cars in the world. This car was in service from 1912 into the 1930s and was displayed at the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, coupled with the Baptist chapel car, Grace.[6][19][2][23] It is now at the St. Catherine of Siena Catholic Church in Wake Forest, North Carolina.

Blessing of the chapel car in Dayton, Ohio.

Blessing of the chapel car in Dayton, Ohio. Interior of the chapel car.

Interior of the chapel car. Depiction of the interior and exterior of the St. Peter chapel car.

Depiction of the interior and exterior of the St. Peter chapel car. Exterior of the car.

Exterior of the car.

St. Paul

The last and largest of the Catholic chapel cars, the St. Paul was also donated by Peter Kuntz. Measuring 86 feet long, it was built by Chicago's Pullman Company. Dedicated in New Orleans on March 14, 1915, it served primarily in Louisiana, Texas, North Carolina and Oklahoma. By 1936, both St. Peter and St. Paul were in storage, with St. Paul being sent to the Bishop of Great Falls, Montana, for use in the diocese. The chapel car was sold to Montana state Senator Charles Bovey for his railroad museum in 1967. In 1996, the chapel car was involved in a trade between the museum and the Escanaba-Lake Superior Railroad.[2][1][6]

The floor plan of the chapel car St. Paul.

The floor plan of the chapel car St. Paul. Interior of the St Paul chapel car.

Interior of the St Paul chapel car. Photo of the exterior of the St. Paul.

Photo of the exterior of the St. Paul.

References

- "Chapel car". Pullman Museum. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- Taylor, Wilma Rugh; Taylor, Norman Thomas, eds. (1999). This Train is Bound For Glory: The Story of America's Chapel Cars. Judson Books. p. 382. ISBN 0-8170-1284-2. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- Graves, Dan. "Inexpensive Chapels on Wheels". Christianity.com. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- The best-known chapel car on the Trans-Siberian Railway was built in 1896 by the Putilov Works in St. Petersburg. Illustrations of it appeared in Burton Holmes' account of his travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1901, and also in Le Patriote Illustré (Paris) of 19 June 1904. Holmes' travel account included photographs of both the exterior (showing that it had been modified with the addition of a side door) and the interior (looking toward the iconostasis). The lithograph from Le Patriote Illusté also depicted the iconostasis. A photograph of the car as originally built is available at the Sibiria [sic] Photo Archive: http://archive.yourmuseum.ru/project/sib-foto/transsib/stations/st6.htm

- Walrath, Harry R. "God Rides the Rails: Chapel Cars on the Nation's Railroads". Frontier Trails. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- "Chapel Cars of America". Chapel Cars.com. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- "A Cathedral on Wheels" (PDF). New York Times. 13 November 1890. Retrieved 5 December 2011. (PDF)

- "The Ontonagon Fire". The Ontonagon Herald. 5 September 1896. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "The Great Progress That Has Been Made In Minnesota" (PDF). New York Times. 3 February 1891. Retrieved 6 December 2011. (PDF)

- "John D. Adorns a Church With Daisies" (PDF). New York Times. 23 June 1913. Retrieved 6 December 2011. (PDF)

- "Emmanuel Chapel railroad car". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Chapel Car Emmanuel". Prairie Village.org. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "History of the Messenger of Peace Car". Northwest Railway Museum. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Saving Messenger of Peace". Northwest Railway Museum. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Rehabilitation of the chapel car". Northwest Railway Museum. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Catchpole, Dan (16 February 2011). "Railway Museum hosts benefit to restore Chapel Car 5". SnoValley Star. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Historic Messenger of Peace railroad chapel car begins long road to restoration". Encyclopedia of Washington State History Online. 13 September 2001. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Chapel Car Dedicated" (PDF). New York Times. 28 May 1900. Retrieved 6 December 2011. (PDF)

- "St. Anthony Parish, Portland Oregon". Parishes Online. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "The Catholic Church Extension Society". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "A Catholic Chapel Car" (PDF). New York Times. 4 April 1907. Retrieved 6 December 2011. (PDF)

- "Famous chapel on wheels visits Washington". Library of Congress. 16 July 1931. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "This Church Is On Wheels" (PDF). New York Times. 6 October 1913. Retrieved 6 December 2011. (PDF)