SEPTA Regional Rail

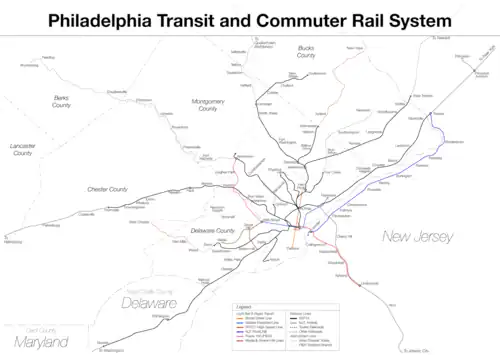

The SEPTA Regional Rail system (reporting marks SEPA, SPAX) is a commuter rail network owned by SEPTA and serving the Philadelphia metropolitan area. The system has 13 branches and more than 150 active stations in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, its suburbs and satellite towns and cities. It is the sixth-busiest commuter railroad in the United States, and the busiest outside of the New York, Chicago, and Boston metropolitan areas. In 2016, the Regional Rail system had an average of 132,000 daily riders [5] and 118,800 daily riders as of 2019.[1]

| SEPTA Regional Rail | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

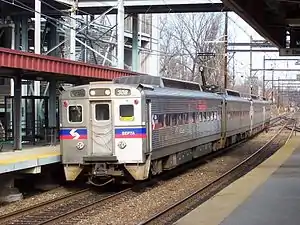

A SEPTA Regional Rail train at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia | |||

| Overview | |||

| Owner | Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) | ||

| Area served | Delaware Valley | ||

| Transit type | Regional rail | ||

| Number of lines | 13 | ||

| Number of stations | 155[1] | ||

| Daily ridership | 62,800 (weekdays, Q2 2023) [2] | ||

| Annual ridership | 15,907,400 (2022) [3] | ||

| Headquarters | 1234 Market Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107 | ||

| Website | septa | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | Assumed operations in 1976, officially established 1983 | ||

| Reporting marks | SEPA, SPAX | ||

| Infrastructure manager(s) | |||

| Number of vehicles | 404 revenue vehicles as of 2015[4] | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | Total: 280 mi (450 km)[4]

| ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||

| Electrification | Overhead line, 12 kV 25 Hz AC: Amtrak's 25 Hz traction power system SEPTA's 25 Hz traction power system | ||

| |||

The core of the Regional Rail system is the Center City Commuter Connection, a tunnel linking three Center City stations: the above-ground upper level of 30th Street Station, the underground Suburban Station, and Jefferson Station. All trains stop at these Center City stations; most also stop at Temple University station on the campus of Temple University in North Philadelphia. Operations are handled by the SEPTA Railroad Division.[6]

Of the 13 branches, six were originally owned and operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) (later Penn Central), six by the Reading Company, while one was constructed under SEPTA in 1985. The PRR lines terminated at Suburban Station; the Reading lines at Reading Terminal. The Center City Commuter Connection opened in November 1984 to unite the two systems, turning the two terminal stations into through-stations. Reading Terminal was replaced by the newly built underground Market East Station (now Jefferson Station). Most inbound trains from one line continue on as outbound trains on another line. Some limited or express trains, and all trains on the Cynwyd Line, terminate on one of the stub-end tracks at Suburban Station. Service on most lines operates from 5:30 a.m. to midnight.

Lines

Each former PRR line, as well as the Airport Line, was once paired with a former Reading line and numbered from R1 to R8 (except for R4), so that one route number described two lines, one on the PRR side and one on the Reading side. This was ultimately deemed more confusing than helpful, so on July 25, 2010, SEPTA dropped the R-number and color-coded route designators and changed dispatching patterns so fewer trains follow both sides of the same route.[7]

Former Pennsylvania Railroad lines

- Airport Line: terminates at the Philadelphia International Airport. This line is geographically on the PRR side of the system, however service did not begin on the line until 1985.

- Chestnut Hill West Line: terminates in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia.

- Cynwyd Line: terminates in Cynwyd and operates weekdays only. Until 1986, trains continued on to Ivy Ridge station in northwestern Philadelphia.

- Media/Wawa Line: terminates at Wawa. Until 1986, trains continued on to West Chester. SEPTA restored service to Wawa, approximately three miles (5 km) west of the previous terminus at Elwyn, on August 21, 2022.

- Paoli/Thorndale Line: trains terminate at Malvern or Thorndale; additional rush hour trains terminate at Bryn Mawr or Paoli.[8] From April 2, 1990 to November 11, 1996, trains continued on to Parkesburg. Service was extended to Thorndale on November 22, 1999. In March 2019, SEPTA announced a plan to extend service to Coatesville, approximately three miles west of Thorndale, once a new train station is constructed.[9]

- Trenton Line: terminates in Trenton, New Jersey. This line uses Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, and offers a connection at Trenton to New Jersey Transit's Northeast Corridor Line for continued service to New York City.

- Wilmington/Newark Line: terminates in Wilmington, Delaware, with some weekday trains continuing to Newark, Delaware. The Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT) subsidizes Delaware service. This line runs entirely on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.

Former Reading Company lines

- Chestnut Hill East Line: terminates in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia.

- Fox Chase Line: terminates in the Fox Chase section of Philadelphia.

- Lansdale/Doylestown Line: terminates at Doylestown. On weekdays, approximately half of the local trains terminate at Lansdale while the remainder of the local trains, and some expresses, continue on to Doylestown.

- Manayunk/Norristown Line: terminates at Elm Street in Norristown.

- Warminster Line: terminates in Warminster.

- West Trenton Line: terminates at the West Trenton station in Ewing, New Jersey.

| Line | Inbound Terminal(s) | Outbound Terminal(s) | Stations | Length[10] | Daily weekday boardings (2019)[10] | County(s) Served[10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airport | Temple University | Philadelphia International Airport Terminals E & F | 10 | 20.2 mi (32.5 km) | 4,686 | Montgomery County, Philadelphia County, Delaware County |

| Chestnut Hill East | 30th Street Station | Chestnut Hill East | 14 | 12.2 mi (19.6 km) | 3,874 | Philadelphia |

| Chestnut Hill West | Temple University | Chestnut Hill West | 14 | 14.7 mi (23.7 km) | 4,463 | Philadelphia |

| Cynwyd | Suburban Station | Cynwyd | 7 | 6.1 mi (9.8 km) | 505 | Philadelphia, Montgomery County |

| Fox Chase | 30th Street Station | Fox Chase | 10 | 12.5 mi (20.1 km) | 4,560 | Philadelphia |

| Lansdale/Doylestown | 30th Street Station | Lansdale, Doylestown | 28 | 35.8 mi (57.6 km) | 17,306 | Philadelphia, Montgomery, Bucks |

| Manayunk/Norristown | 30th Street Station | Miquon, Norristown Transportation Center, Elm Street | 16 | 19.5 mi (31.4 km) | 11,486 | Philadelphia, Montgomery County |

| Media/Wawa | Temple University | Media, Elwyn, Wawa | 19 | 18.1 mi (29.1 km) | 11,202 | Philadelphia, Delaware |

| Paoli/Thorndale | Temple University | Bryn Mawr, Malvern, Thorndale | 22 | 37.9 mi (61.0 km) | 21,284 | Philadelphia County, Montgomery County, Delaware County, Chester County |

| Trenton | Temple University | Trenton Transit Center | 15 | 36.4 mi (58.6 km) | 11,132 | Philadelphia, Bucks, Mercer (NJ) |

| Warminster | 30th Street Station | Glenside, Warminster | 17 | 22.3 mi (35.9 km) | 7,667 | Philadelphia, Montgomery, Bucks |

| West Trenton | 30th Street Station | West Trenton | 23 | 34.7 mi (55.8 km) | 12,031 | Philadelphia, Montgomery, Bucks, Mercer (NJ) |

| Wilmington/Newark | Temple University | Marcus Hook, Wilmington, Newark | 22 | 41.1 mi (66.1 km) | 8,917 | Philadelphia, Delaware, New Castle (DE) |

Stations

There are 154 active stations on the Regional Rail system (as of 2016), including 51 in the city of Philadelphia, 42 in Montgomery County, 29 in Delaware County, 16 in Bucks County, 10 in Chester County, and six outside the state of Pennsylvania (two in Mercer County, New Jersey and four in New Castle County, Delaware). In 2003, passengers boarding in Philadelphia accounted for 61% of trips on a typical weekday, with 45% from the three Center City stations and Temple University station.

| County | Stations | Boardings in 2003 | Boardings in 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philadelphia | 51 | 60 967 | 61 970 |

| Montgomery County | 42 | 17 228 | 18 334 |

| Delaware County | 29 | 8 310 | 8 745 |

| Bucks County | 16 | 5 332 | 5 845 |

| Chester County | 10 | 5 154 | 5 079 |

| Outside Pennsylvania | 6 | 2 860 | 3 423 |

| total | 154 | 99 851 | 103 396 |

Rolling stock

SEPTA uses a mixed fleet of General Electric and Hyundai Rotem "Silverliner" electric multiple unit (EMU) cars, used on all Regional Rail lines. SEPTA also uses push-pull equipment: coaches built by Bombardier, hauled by ACS-64 electric locomotives similar to those used by Amtrak. The push-pull equipment is used primarily for peak express service because it accelerates slower than EMU equipment, making it less suitable for local service with close station spacing and frequent stops and starts.

As of 2012, all cars have a blended red-and-blue SEPTA window logo and "ditch lights" that flash at grade crossings and when "deadheading" through stations, as required by Amtrak for operations on the Northeast and Keystone Corridors. SEPTA's railroad reporting mark SEPA is the official mark for their revenue equipment, though it is rarely seen on external markings. SPAX can be seen on non-revenue work equipment, including boxcars, diesel locomotives, and other rolling stock.

The Silverliner coaches were first built by Budd in Philadelphia and used by the PRR in 1958 as a prototype intercity EMU alternative to the GG1-hauled trains. Similarly designed cars were purchased in 1963 as the Silverliner II, in 1967 as the Silverliner III, and the Silverliner IV in 1973.

The Silverliner V, a more modern version of the railcar was introduced in 2010.[11] A total of 120 cars were purchased for $274 million, and they were constructed in facilities located in South Philadelphia and South Korea by Hyundai Rotem.[11][12] The cars were built with wider seats and quarter point doors for easier boarding or departing at high-level stations in Center City. The Silverliner V cars represent one-third of SEPTA's regional rail fleet.[13]

In late 2014, and the beginning of early 2015, SEPTA began the "Rebuilding for the Future" campaign that will replace all deteriorated rolling stock and rail lines with new, modernized, equipment, including ACS-64 locomotives, bi-level cars, and better signaling. The ACS-64 locomotives for push-pull trains arrived in 2018.

SEPTA passenger rolling stock includes:

Electric multiple units

| Year | Make | Model | Numbers | Type | Total | Tare (Ton/t) |

Seats | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973–76 | GE | Silverliner IV | 101–188 | married pairs | 88 | 62.5/56.8 | 125 | Ex-Reading |

| 304–399 | 95 | Ex-Penn Central | ||||||

| 417–460 | 44 | Units renumbered when PCB transformers were replaced with silicone transformers. | ||||||

| 276–303 | single cars | 28 | ||||||

| 400–416 | 16 | Units renumbered when PCB transformers were replaced with silicone transformers. | ||||||

| 2010–13 | Rotem | Silverliner V | 701–738 | single cars | 38 | 62.5/56.8 | 110 | Replacements for 70 older Silverliner II and Silverliner III cars; will also add capacity.[12] First three cars entered revenue service October 29, 2010; delivery completed as of March 21, 2013. In July 2016, all units temporarily withdrawn due to cracks on some of the components and began returning to service in September 2016. |

| 801–882 | married pairs | 82 |

Push-pull passenger cars

| Year | Make | Model | Type | Numbers | Total | Tare (Ton/t) |

Seats | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Bombardier | SEPTA I | Cab cars | 2401–2410 | 10 | 50/45.4 | 118 | |

| Trailers | 2501–2525 | 25 | 131 | |||||

| 1999 | SEPTA II | Trailers | 2550–2559 | 10 | 117 | These cars have a center door on each side for high level only boarding. | ||

| CRRC MA | TBD (bilevel rail car) |

Cab cars | 11 | 134 | Ordered in March 2017 with options for 10 more cars.[14] Deliveries were begin in July 2022.[15] Delayed.[16][17] | |||

| Trailers | 34 | 139 |

Electrification

All lines used by SEPTA are electrified with overhead catenary supplying alternating current at 12 kV with a frequency of 25 Hz. The system on the former PRR side is owned and operated by Amtrak, part of the electrification of the Northeast Corridor. The electrification on the Reading side is owned by SEPTA. The Amtrak system was originally built by the PRR between 1915 and 1938. The SEPTA-owned system was originally built by the Reading starting in 1931. The two systems are not electrically connected. After construction of the Center City Commuter Connection, the two electrical systems now meet near Girard Avenue at a “phase break,” a short section of unpowered track, which trains coast across. The gap is necessary because the two electrical systems are not kept in synchronization with each other.

The entire system uses 12 kV / 25 Hz overhead catenary lines that were erected by the PRR and Reading railroads between 1915 and 1938. All current SEPTA equipment is compatible with the power supplies on both the ex-PRR (Amtrak-supplied) and ex-Reading (SEPTA-supplied) sides of the system; the "phase break" is at the northern entrance to the Center City commuter tunnel between Jefferson Station and Temple University Station.

Yards and maintenance facilities

SEPTA has four major yards and facilities for the storage and maintenance of regional rail trains:

- Frazer Yard, in Frazer, Pennsylvania, along the Paoli/Thorndale Line; services push-pull train sets.

- Overbrook Maintenance Facility, near Overbrook station on the Paoli/Thorndale Line; Services EMUs

- Powelton Yard, adjacent to 30th Street Station

- Roberts Yard, adjacent to Wayne Junction

History

SEPTA was created to prevent passenger railroads and other mass transit services from disappearing or shrinking in the region. Passenger rail service was previously provided by for-profit companies, but by the 1960s the profitability had eroded, not least because huge growth of automobile use over the previous 30 years had reduced ridership. SEPTA's creation provided government subsidies to such operations and thus kept them from closing down. For the railroads, at first it was a matter of paying the existing railroad companies to continue passenger service. In 1966 SEPTA had contracts with the PRR and Reading to continue commuter rail services in the Philadelphia region.[19]

The Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Company

The PRR and Reading operated both passenger and freight trains along their tracks in the Philadelphia region. Starting in 1915, both companies electrified their busiest lines to improve the efficiency of their passenger service. They used an overhead catenary trolley wire energized at 11,000 volts single-phase alternating current at 25 Hertz (Hz).[20] The PRR electrified the Paoli line in 1915, the Chestnut Hill West line in 1918, and the Media/West Chester and Wilmington lines in 1928. Both railroads continued electrifying lines into the 1930s, replacing trains pulled by steam locomotives with electric multiple unit cars and locomotives. PRR electrification reached Trenton and Norristown in 1930. Reading began electrified operation in 1931 to West Trenton, Hatboro (extended to Warminster in 1974) and Doylestown; and in 1933 to Chestnut Hill East and Norristown. The notable exception was the line to Newtown, the Reading's only suburban route not electrified. While the PRR expanded electrification throughout the northeast (ultimately stretching from Washington, D.C. to New York City), the Reading never expanded electric lines beyond the Philadelphia commuter district.[21]

By the late 1950s, commuter service had become a drag on profitability for the PRR and Reading, like most railroads of the era. Commuter service requires large amounts of equipment, large numbers of employees to operate equipment and station sites, and large amounts of maintenance on track that see extremely heavy usage for only six hours a day, five days a week.[19] Meanwhile, the rise in automobile ownership and the building of the Interstate Highway System chipped away at the steady patronage as population in the suburbs grew. When the Philadelphia suburbs were small towns, people lived close enough to a train station to walk to and from the trains. When the suburbs expanded into what had been fields and pastures, the trip to the station required an automobile, leading commuters to remain in their cars and drive all the way into the city as a matter of convenience.[19]

Both railroads shed a few minor money-losing routes, but more major pruning efforts ran into public opposition and government regulation.[21] Ending a major line involved hearings before the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), the predecessor to the Surface Transportation Board, which moved at a glacial pace and was capricious in the matter of approval, requiring one railroad to continue operating a local train on a route covered by four other trains while allowing another to discontinue a well-patronized train that had no competing lines.[19] In response, the railroads made commuting unpleasant for passengers by neglecting the upkeep of equipment.[19]

Faced with the possible loss of commuter service, local business interests, politicians, and the railroad unions in Philadelphia pushed for limited government subsidization.[21] In 1958, the city enacted the Philadelphia Passenger Service Improvement Corporation (PSIC), which consisted of a partnership with the Reading and PRR to subsidize service on both Chestnut Hill branches.[21] This was not enough to reverse the deterioration of the railroad infrastructure. By 1960, the PSIC assisted with services reaching as far as the city border in all directions. PSIC subsidized trains to Manayunk on the PRR's Schuylkill Branch[21] to Shawmont on the Reading Norristown line, to Fox Chase on the Reading Newtown line, and as far as Torresdale on the PRR's northeast corridor to New York City.[21] Subsequently, the city purchased new trains. The success of the PSIC subsidy program resulted in its expanding throughout the five-county suburban area under the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Compact (SEPACT) in 1962.[21] In 1966, SEPTA began contracts with the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Company to subsidize their commuter lines.

Still, the subsidies could not save the big railroads. The PRR attempted to stay solvent by merging with the New York Central Railroad on February 1, 1968, but the resulting company, Penn Central, went bankrupt on June 21, 1970. The Reading filed for bankruptcy in 1971.[19] Between 1974 and 1976, SEPTA ordered and accepted the delivery of the Silverliner IVs.

Conrail

In 1976, Conrail took over the railroad-related assets and operations of the bankrupt PRR and Reading railroads, including the commuter rail operations. Conrail provided commuter rail services under contract to SEPTA until January 1, 1983, when SEPTA assumed operations.[19]

The end of diesel routes

The Regional Rail SEPTA inherited from Conrail and its predecessor railroads was almost entirely run with electric-powered multiple unit cars and locomotives. However, Conrail (the Reading before 1976) operated four SEPTA-branded routes under contract throughout the 1970s, all of which originated from Reading Terminal. The Allentown via Bethlehem, Quakertown, and Lansdale service was gradually cut back. Allentown–Bethlehem service ended in 1979,[21] Bethlehem-Quakertown service ended July 1, 1981, and Quakertown–Lansdale service ended July 27, 1981. Pottsville line service to Pottsville via Reading and Norristown, also ended July 27, 1981. West Trenton service previously ran to Newark Penn Station; this was cut back to West Trenton on July 1, 1981, with replacement New Jersey Transit connecting service continuing until December 1982.[22] The final service, Fox Chase-Newtown service, initially ended on July 1, 1981. It was re-established on October 5, 1981, as the Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line, which then ended on January 14, 1983.[21]

Most train equipment was either Budd Rail Diesel Cars, or locomotive-hauled push-pull trains with former Reading FP7s. The diesel equipment was maintained at the Reading Company/Conrail owned Reading Shops, in Reading, PA.

The services were phased out due to a number of reasons that included lack of ridership, a lack of funding outside the five-county area, withdrawal of Conrail as a contract carrier, a small pool of aging equipment that needed replacement, and a lack of SEPTA-owned diesel maintenance infrastructure. The death knell for any resumption of diesel service was the Center City Commuter Connection tunnel project, which lacks the necessary ventilation for exhaust-producing locomotives.[23]

Service from Cynwyd was extended to a new high-level station at Ivy Ridge in 1980, and the 52nd Street Station closed in the same year.

SEPTA takeover and strike

The transition from Conrail to SEPTA, overseen by General Manager David L. Gunn (who later became President of the New York City Transit Authority and Amtrak), was a turbulent one.[19] SEPTA attempted to impose lower transit (bus and subway driver's) pay scales and work rules, which was met by resistance by the BLE (an experiment was already in place on the diesel-only Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line, which used City Transit Division employees instead of traditional railroad employees as a bargaining chip). As the January 1, 1983 deadline approached, the unions stated they agreed to work even if new union contracts were not in place by the new year.[21] SEPTA had spent most of December 1982 preparing riders for the likelihood of no train service come the new year.[21] Even with the unions' offers to continue working, SEPTA insisted that a brief shutdown of service would still be necessary, arguing that it would not know until the eleventh hour how many Conrail employees would actually come to work for SEPTA.[21] In addition, SEPTA claimed that these employees would have to be qualified to work on portions of the system unfamiliar to them.[21]

A lawyer who regularly commuted from Newtown on the Fox Chase Rapid Transit line filed a class action lawsuit against SEPTA to force the agency to keep trains running.[21] The judge who heard the case, while agreeing that SEPTA probably would not be able initially to operate a full schedule, ordered the agency to keep as much train service running as possible.[21] This resulted in limited service after January 1, 1983 on all the Reading lines and the heavily patronized PRR Paoli line.[21] Full service was gradually restored over the next several weeks.[21]

The unions then surprised SEPTA on March 15, 1983, by going on strike, still without contracts, in an action timed to coincide with an expected City Transit Division strike.[21] At the time, the City Transit Division was chafing at SEPTA for discontinuing diesel service on the Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line on January 14, 1983, as personnel were paid higher salaries for traveling a considerable distance to operate trains based in Newtown.[21] SEPTA, however, settled with the transit union shortly before its strike deadline, a move that rail unions took as a betrayal.[21] The rail unions had hoped that with both the railroads and City Transit shut down, the unions could extract whatever settlement they desired.[19] The railroad strike lasted 108 days, and service did not resume until July 3, 1983, when the last holdout union agreed to a contract to settle from the other rail unions.[21]

In the end, SEPTA would treat the rail unions workers as railroad workers rather than transit operators, but their pay scale remains lower than that of other Northeast commuter railroads, such as NJ Transit and the Long Island Rail Road. The strike resulted in lower ridership, which took over 10 years to rebuild.

Center City tunnel

The idea of linking the Philadelphia and Reading lines with an urban tunnel was first adopted by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission in 1960, under the leadership of Edmund Bacon.[24] Such a tunnel would improve the connectivity of the network.[25] The tunnel was constructed between 1976 and 1984 at a cost of $330 million.[26]

As part of the tunnel project SEPTA implemented a diametrical mode of operation. Heretofore the Pennsylvania and Reading trains had terminated in their respective terminals. Besides making transfers difficult, this led to congestion and reduced capacity. With the opening of the tunnel, Pennsylvania trains would run through the tunnel on to matched Reading lines, and vice versa. This would reduce congestion at the downtown stations, as very few trains would terminate or originate at them, and reduce the number of potential passenger transfers as each train reached more destinations. The original plan for the system was made by University of Pennsylvania professor Vukan Vuchic, based on the S-Bahn commuter rail systems in Germany. Numbers were assigned to the Pennsylvania lines in order from south (Airport) to northeast (Trenton); the Reading line matches were chosen to balance ridership, the physical characteristics of the lines, and the location of yards. An additional consideration was avoiding crossovers on the trunk lines. and to attempt to avoid trains running full on one side and then running mostly empty on the other.[27] Vuchic recommended seven lines:[28]

| Line | Stage 1 | Stage 2 |

|---|---|---|

| R1 | Airport to West Trenton | Airport to West Trenton |

| R2 | Marcus Hook to Warminster | Marcus Hook to Warminster |

| R3 | West Chester/Elwyn to Wayne Junction/Suburban Station | West Chester/Elwyn to Chestnut Hill West |

| R4 | Bryn Mawr to Wayne Junction/Suburban Station | Bryn Mawr to Fox Chase/Newtown |

| R4S | Fox Chase to Newtown | |

| R5 | Paoli to Doylestown/Lansdale | Paoli to Doylestown/Lansdale |

| R6 | Ivy Ridge to Norristown | Ivy Ridge to Norristown |

| R7 | Trenton to Chestnut Hill East | Trenton to Chestnut Hill East |

| R8 | Chestnut Hill West to Fox Chase |

Stage 1, which represented the state of affairs when the tunnel opened in 1984, was hampered by an "imbalance" between the Pennsylvania lines and Reading lines. Both the R3 and R4 would short turn at Wayne Junction or Suburban Station (as would some R7 trains), which cut against the diametrical principle.[29] To correct this, Vuchich proposed the construction of a connection in the Swampoodle neighborhood between the ex-Pennsylvania Chestnut Hill West Line and the ex-Reading trunk line west of Wayne Junction as part of Stage 2, moving the Chestnut Hill West line to the "Reading" side.[30] This connection was never built, leading (among other factors) to the following changes:

- R3 could not go to Chestnut Hill West, so R3 trains from Media/West Chester instead went to West Trenton along the R1. Service to Chestnut Hill West was picked up by the R8.

- R4 was dropped; The R5 Paoli runs local along its entire length most of the time, and Fox Chase became half of the R8.

- R8 was added for Fox Chase to Chestnut Hill West service, using the former R4-Fox Chase and R3-Chestnut Hill West halves.

One of the assumptions in this plan was that ridership would increase after the connection was open. Instead, ridership dropped after the 1983 strike. While recent rises in oil prices have resulted in increased rail ridership for daily commuters, many off-peak trains run with few riders. Pairing up the rail lines based on ridership is less relevant today than it was when the system was implemented.

At a later time, R1 was applied to the former Reading side, shared with the R2 and R5 lines to Glenside station, and R3 to Jenkintown, and R1-Airport trains ran to Glenside station rather than becoming R3 trains to West Trenton. In later years, SEPTA became more flexible in order to cope with differences in ridership on various lines. After the original service patterns were introduced, the following termini changed:

- R2 – Marcus Hook was extended to Wilmington and Newark

- R3 – West Chester was cut back to Elwyn

- R5 – Paoli was extended to Downingtown and Parkesburg, then later cut back to Downingtown, and later re-extended to Thorndale

- R6 – Ivy Ridge was cut back to Cynwyd

On July 25, 2010, the R-numbering system was dropped and each branch was named after its primary outer terminals.[31]

Crises

The 1980s and 1990s were difficult times for SEPTA. While the agency has spent most of its 50-year history staggering from crisis to crisis, the 1980s were a particularly low point. The era was defined by crippling strikes, engineer shortages, drastic service cuts and an abundance of mismanagement. State and local officials, commuters, and general observers were quick to brand SEPTA as the most inept of all the major transit agencies, though getting a handle on what exactly was the cause of its ills was historically difficult.[32]

Railpace Newsmagazine contributor Gerry Williams commented that understanding what routinely transpires in SEPTA upper management rarely made itself clearly known to the general public. Frequently, there were various hidden agendas working in the background, often working at cross purposes with one another. This was often the result of the city (Philadelphia)/Suburban (Bucks, Delaware, Chester, Montgomery) split. The city government had historically been Democratic, the four suburban counties Republican until 2019, when all four suburban counties elected Democratic leadership. This factor is regularly influenced by the changing political winds at the state capital in Harrisburg.[32]

In addition, unlike all other U.S. railroad commuter agencies which are a state agency operated as a leg of its corresponding Department of Transportation, SEPTA is not a state agency and is beholden primarily to the five local governments which comprise it. Williams questioned why there has never been any massive public push to force SEPTA to "clean up its act." He concluded that the crisis within SEPTA "merely reflects the broader problems of local provincialism and petty political squabbles which are so rampant within the region."[32] Williams later commented that "unfortunately, there does not seem to be any group out there influential enough to bring shame on SEPTA, and SEPTA just may be beyond shaming anyway."[32]

Expansion

Service to Reading Terminal ended on November 6, 1984, in anticipation of the opening of the Center City Commuter Connection, which opened on November 12, 1984. The tunnel, first proposed in the 1950s, is an underground connection between PRR and Reading lines; previously, PRR commuter trains terminated at Suburban Station and Reading at Reading Terminal. The connection converted Suburban Station into a through-station and rerouted Reading trains down a steep incline and into a tunnel that turns sharply west near the new Market East Station (now Jefferson Station). The conversion was meant to increase efficiency and reduce the number of tracks needed.[19] On April 28, 1985, the Airport Line opened, providing service from Suburban Station via 30th Street Station to Philadelphia International Airport. This line runs along Amtrak's NEC, then crosses over onto Reading tracks that pass close to the airport. At the airport, a new bridge carries it over Interstate 95 and into the airport terminals between the baggage claim in arrivals and the check-in counters in departures.[19] In 1990, R5 service was extended from Downingtown to Coatesville and Parkesburg. However, on November 10, 1996, R5 service to Parkesburg was truncated to Downingtown. In 2006, SEPTA started negotiations with Wawa Food Markets to purchase land in Wawa, Pennsylvania to build a new Park-and-Ride facility for a planned restoration of service between Elwyn and Wawa on the Media/Wawa Line, which previously ran to West Chester.

Shrinking service

Between 1979 and 1983, diesel locomotives were phased out. With insufficient operating funds and a desire to avoid maintaining deteriorating lines, SEPTA cut various services throughout the 1980s.[33] R3 West Chester service was truncated to Elwyn on September 19, 1986, due to unsatisfactory track beyond. R6 Ivy Ridge service was truncated to Cynwyd on May 17, 1986, due to concerns about the Manayunk Bridge over the Schuylkill River.[34] Service to Cynwyd ended altogether in 1988, but fierce political pressure brought resumed service. R8 diesel service between Fox Chase and Newtown ended on January 14, 1983, after SEPTA decided not to repair failing diesel train equipment.[35][21] The service was initially terminated on July 1, 1981 (along with diesel services to Allentown and Pottsville) and reinstated on October 5, 1981, using operators from the city transit division. This experimental Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line caused a rift in unions within the organization, adding to the March 1983 strike that lasted 108 days.[36]

SEPTA management was criticized for the cuts. Vukan Vuchic, the transit expert and University of Pennsylvania professor who designed the former R-numbering system for SEPTA, said he had never seen a city the size of Philadelphia "cut transit services quite as drastically as SEPTA. For a system that is already obsolete, any more cutbacks would be disastrous—and likely spell doom for transit in the Philadelphia region. This city would be the first in the world to do that."[37]

DVARP said that SEPTA purposely truncated service and that while other commuter railroad counterparts "in North America expand their rail services, SEPTA is the only one continuing to cut and cut and cut. The only difference between SEPTA and its railroad and transit predecessors is that SEPTA eliminates services to avoid rebuilding assets, while its predecessors (PRR, Reading and Conrail) kept service running while deferring maintenance."[33]

RailWorks

On November 16, 1984, the Columbia Avenue (now Cecil B. Moore Avenue) bridge near old Temple University Station was found to be unsafe, putting all four tracks out of service north of Market East Station. In December 1984, a temporary bridge opened, allowing service to resume north of Market East Station. Nonetheless, the results of decades of deferred maintenance on the Reading Viaduct between the Center City Commuter Connection and Wayne Junction continued to threaten the right-of-way. In 1992, the bridge was in such poor condition that the bridge inspector actually saw the structure sag every time a train passed over the bridge; further inspection revealed that the bridge was in imminent danger of collapsing.[21]

Over the following year, SEPTA undertook a 10-month, $354 million (equivalent to $738.2 million in 2023) project to overhaul the viaduct, labeled "RailWorks."[21] The viaduct was shut down completely from April 5 to October 3, 1992, and from May 2 to September 4, 1993, with the R6 Norristown, R7 Chestnut Hill East, and R8 Fox Chase lines suspended.[21][38][39] Other Reading lines only came as far into the city as the Fern Rock Transportation Center, where riders had to transfer to the Broad Street Line.[21] Express trackage was added to the Broad Street Line to improve travel times from Center City to Fern Rock. Nonetheless, the number of subway trains needed to carry both regular Broad Street Line riders, as well as passengers transferring to the subway because of RailWorks, exceeded the capacity of the above-ground, two-track, stub-end Fern Rock terminus.[21][40] In 1993, SEPTA added a loop track to Fern Rock Yard, so that northbound trains did not need to use the crossovers at the station throat, somewhat ameliorating the problem.[21] During peak hours, SEPTA ran several diesel trains from the Reading side branches, along non-electrified Conrail trackage, to 30th Street Station.[21]

Meanwhile, SEPTA crews replaced several dilapidated bridges, installed new continuous welded rail and overhead catenary, constructed new rail stations at Temple University and North Broad Street, and upgraded the signals.[21] Upon the completion of RailWorks, the Reading Viaduct became the "newest" piece of railroad owned by SEPTA, although other projects have since allowed improved service on the ex-Reading side of the system.[21]

Ridership

When Conrail handled operations on SEPTA's behalf, overall ridership peaked in 1980 with over 373 million unlinked trips per year. The Regional Rail Division carried over 32 million passengers in 1980, a level which was not to be exceeded again for decades. Regional Rail ridership subsequently declined in 1982 after SEPTA ceased operating diesel service. It then sharply declined by half after SEPTA assumed operations in 1983, hitting a new low of just under 13 million passengers. This decline of ridership was the result of a drawn-out strike by the railroad unions, the discontinuing of service to over 60 stations, the increase in fares during a period of decreasing gasoline prices, and the unfamiliarity of SEPTA's management in operating a commuter railroad.

In 1992, ridership dipped again due to economic factors and due to SEPTA's RailWorks project, which shut down half of the railroad over two periods of several months each in 1992 and 1993. A mild recession in 1992–1994 also dampened ridership, but a booming economy in the late 1990s helped increase ridership to near the peak level of 1980.

In 2000, ridership started a slight decline due to the slow economy, but in 2003 ridership started increasing again. The average weekday passenger counts have not increased at the same rate as the total annual passenger counts, which may mean that weekend ridership is increasing. In 2008, Regional Rail ridership hit an all-time high of over 35 million. In 2009, it was down 1% of this high, but by fiscal year 2013 ridership reached a new high of over 36 million.[41] This number was passed again in 2015 with a new record of 37.7 million trips.[42]

The following chart shows SEPTA Regional Rail ridership from 1979 to 2021:[43][44][45][46][47][48][49][42]

2014 strike

On June 14, 2014, a strike shut down SEPTA's Regional Rail service after negotiations failed between SEPTA and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. A total of 400 workers walked off the job.[50][51] As a result of the strike, SEPTA planned to add additional capacity on bus, subway, and trolley routes along with the Norristown High Speed Line during off-peak hours.[51] On the first day of the strike, Governor Tom Corbett asked President Barack Obama to appoint a presidential emergency board to attempt to end the labor dispute and force employees back to work.[51] A short time after 7 p.m. on June 14, President Obama signed an executive order forcing workers to return and continue negotiations through the presidential emergency board. SEPTA Regional Rail service resumed on June 15.[52]

COVID-19 measures (2020-2021)

SEPTA Regional Rail operated "Lifeline Service" during the COVID-19 pandemic.[53] On April 9, 2020, service was suspended on the Chestnut Hill East, Chestnut Hill West, Cynwyd, Manayunk/Norristown, West Trenton, and Wilmington/Newark lines.[54] Service along the Lansdale/Doylestown and Paoli/Thorndale lines were also truncated to Lansdale and Malvern, respectively.[54] Wilmington/Newark Line service as far as Wilmington resumed on May 10, 2020, as part of the Southwest Connection Improvement Program, while service was suspended along the Media/Wawa Line on the same date.[55] The West Trenton Line and Paoli/Thorndale Line service to Thorndale resumed on June 15, 2020. Lansdale/Doylestown Line service to Doylestown resumed on June 22, 2020. The Chestnut Hill East, Manayunk/Norristown, and Media/Elwyn lines resumed on June 28, 2020. On the same date, service levels increased on all lines except the Chestnut Hill West and Cynwyd lines.[54] Service on the Wilmington/Newark Line to Newark resumed on January 25, 2021 in order to offer public transit options during a construction project along Interstate 95 in Wilmington.[56] Service on the Chestnut Hill West Line resumed on March 8, 2021, on a limited schedule, with service running Monday through Friday.[54][57] Service on the Cynwyd Line resumed with limited operations on September 7, 2021.[58] Weekend service on the Chestnut Hill West Line was restored on December 19, 2021.[59]

2045 Philadelphia transit plan

In February 2021, the city government of Philadelphia announced the Philadelphia Transit Plan, which outlines the city's proposals for its public transportation system through 2045. For Regional Rail, the plan included increased service frequency, a fare system overhaul, and the creation of many metro-like Regional Rail lines within the Philadelphia city limits and close suburbs. Regional Rail would be split into the Silver Line, frequent Regional Rail (metro-style lines), and Regional Express Service (lines similar to the current Regional Rail, which would make fewer stops closer to Philadelphia). This plan would require upgraded tracks and stations, new vehicles, and infrastructure replacement and upgrades. Similar to other major infrastructure upgrades to existing commuter networks such as GO Transit Regional Express Rail in Toronto or the Electrification of Caltrain in San Francisco. The plan also proposed extensions of Regional Rail services to Phoenixville, Quakertown, and West Chester.[60][61]

The 2045 Transit Plan breaks this into 3 phases.

Phase 1: "The Silver Line"

Phase 1 entails the creation of the "Silver Line". The name comes from the Silverliner family of EMUs which are used in Regional Rail service, and was chosen to denote the metro-like similarities between the Silver Line and the Blue (Market–Frankford) and Orange (Broad Street) lines. The Silver Line would run from Fern Rock Transportation Center in North Philadelphia to Penn Medicine station in University City. It would have the same frequency as a bus line, with 15-minute headway for 15 hours a day every week. Fares along the Silver Line would be similar to SEPTA's other transportation modes, including bus, trolley, and subway.[60]

Phase 2: Upgrade priority lines

Phase 2 would include the addition of more metro-like regional rail routes. These would be called Frequent Regional Rail lines and would be similar to the Silver Line, having lower fares, free transfers, and increased frequencies. Currently, there are four phase 2 routes proposed, including conversion of the Manayunk/Norristown, Chestnut Hill East, and Airport lines to Frequent Regional Rail, and a portion of the SEPTA Main Line from Fern Rock Transportation Center to Jenkintown–Wyncote station in Jenkintown would have Frequent Regional Rail alongside Regional Express Services.[60]

Phase 3: Full implementation

Phase 3 would include the implementation of the final Frequent Regional Rail lines, additional infrastructure, vehicle, and station upgrades. As part of phase 3, the Chestnut Hill West, Fox Chase, and Warminster lines would be completely replaced with Frequent Regional Rail, while the Lansdale/Doylestown, Media/Wawa, Paoli/Thorndale, and West Trenton lines would have Frequent Regional Rail run alongside Regional Express Services to Lansdale, Elwyn, Villanova, and Somerton respectively.[60]

The city of Philadelphia and SEPTA expect this plan to take decades and billions of dollars to complete.[60]

See also

Notes

- "SEPTA OPERATING FACTS, FY 2019" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- "Transit Ridership Report Second Quarter 2023" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. September 13, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2022" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- "SEPTA OPERATING FACTS, FY 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-07. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- "Revenue & Ridership Performance, February FY2016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- 2008 SEPTA Railroad Division employee timetable Archived 2011-12-09 at the Wayback Machine accessed August 16, 2011

- "SEPTA to Change Regional Rail designations". PlanPhilly. 3 February 2010. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- "Paoli/Thorndale Line Regional Rail Schedule". SEPTA. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- Lucas Rodgers (7 March 2019). "SEPTA Regional Rail set to return to Coatesville". Daily Local News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "SEPTA Route Statistics 2020" (PDF). SEPTA Planning. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- "SEPTA's new railcar model makes inaugural trip". The Philadelphia Inquirer. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 November 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- "SEPTA unveils first Silverliner V train". Progressive Railroading. 3 November 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- Smith, Sandy (2 July 2016). "Details Emerge on SEPTA Silverliner V Defect". Philadelphia Magazine. Metro Corp. Archived from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- "SEPTA awards bid for Chinese bilevel commuter cars". Trains Magazine. March 24, 2017. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "CRRC puts Septa double-deck coach design to the test". International Rail Journal. April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- Fitzgerald, Thomas (2023-03-02). "SEPTA's new railcars plagued by faulty wiring, repeated delays — and a federal investigation". inquirer.com. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- "Transit Briefs: NYMTA/LIRR, SEPTA". Railway Age. 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- Dan, McQuade (November 11, 2015). "SEPTA Is Buying 13 New Locomotives for $113 Million". Philadelphia Magazine. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- Drury, George H. (1992). The Train-Watcher's Guide to North American Railroads: A Contemporary Reference to the Major railroads of the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 19, 150, 201–202, 267. ISBN 0-89024-131-7.

- This is uncommon today; the vast majority of American electrical systems use double-phase, 60 Hz alternating current.

- Williams, Gerry (1998). Trains, Trolleys and Transit: A Guide to Philadelphia Area Rail Transit. Piscataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company, Inc. pp. 13–16, 46–47, 95–98. ISBN 0-9621541-7-2.

- Pawson, John (March 1993). "New Backing for "Crusader" Route". The Delaware Valley Rail Passenger. Delaware Valley Association of Railroad Passengers. 13 (3). Archived from the original on 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- "Philadelphia Trolley Tracks: Diesel Train Service". www.phillytrolley.org. Archived from the original on 2010-12-22. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- Heller & Garvin 2013, p. 140

- Vuchic & Kikuchi 1984, pp. 1–4

- Treese 2012, p. 44

- Vuchic & Kikuchi 1985, pp. 52–57

- Vuchic & Kikuchi 1984, p. 5-2

- Vuchic & Kikuchi 1984, p. 5-1

- Vuchic & Kikuchi 1984, pp. 2–8

- Lustig, David (November 2010). "SEPTA makeover". Trains Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing: 26.

- Williams, Gerry (September 1984). "SEPTA Scene". Railpace Newsmagazine. Picataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company, Inc. 4 (9): 16–18. Archived from the original on 2014-07-01. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- Mitchell, Matthew (April 1992). "SEPTA Budget for Fiscal 1993: Continued Rail Retrenchment". The Delaware Valley Association of Railroad Passengers.

- "The Delaware Valley Rail Passenger". dvarp.org. Delaware Valley Association of Railroad Passengers. June 8, 1992. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- "Abandoned Rails: The Newtown Branch". www.abandonedrails.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-31. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- "Newtown Branch history". Archived from the original on 2011-05-11.

- Hyland, Tim (2004-12-09). "SEPTA in need of new ideas, more funding". Penn Current. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

- Struzzi, Diane (2 April 1992). "Septa Riders Bracing For Railworks". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- Fish, Larry (5 September 1993). "Septa Is Wooing Riders Anew: Railworks Worked. Trains Are Back". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- Darlington, Peggy; Jones, John; Metz, George; Wright, Bob. "SEPTA Broad Street Subway". NYCSubway.org. Archived from the original on 2016-05-14. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- "SEPTA | SEPTA Sets New Record For Regional Rail Ridership". www.septa.org. Archived from the original on 2017-08-25. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- "June & Fiscal Year-End 2021 Report" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- SEPTA 1997 Ridership Census, Annual Service Plans FY 2001 through 2007

- "Philadelphia 2013: The State of the City" (PDF). The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- Glover, Sarah (July 23, 2013). "SEPTA Sets Regional Rail Ridership Record". WCAU. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- "FY 2013 SEPTA annual report" (PDF). SEPTA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- American Public Transportation Association. "Public Transportation Ridership Report: Fourth Quarter & End-of-Year 2014" (PDF). APTA. APTA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- American Public Transportation Association. "Public Transportation Ridership Report: Fourth Quarter 2017" (PDF). APTA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- "Ridership Report". American Public Transportation Association.

- Mulvihill, Geoff (June 14, 2014). "SEPTA Commuter Rail Union on Strike". WCAU. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: NBC10.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- Nussbaum, Paul (June 14, 2014). "Regional Rail strike begins; Corbett to seek federal help". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 16, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- Dougherty, Mike, Jan Carabeo, and Andrew Kramer (June 14, 2014). "Obama Intervenes As SEPTA Regional Rail Strike Ends, Service Resumes Sunday". Philadelphia: KYW-TV. Archived from the original on June 18, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "SEPTA Regional Rail & Rail Transit Lifeline Service" (PDF). SEPTA. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "Service Information". SEPTA. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "Southwest Connection Improvement Program". SEPTA. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "Regional Rail Select Schedule Changes - Select Lines Sunday, January 24, 2021". SEPTA. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- Madej, Patricia (January 28, 2021). "SEPTA Chestnut Hill West Line will return with 'restricted service' in March". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Regional Rail Select Schedule Changes". SEPTA. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- "Regional Rail Select Schedule Changes - New Timetables Effective Sunday, December 19, 2021". SEPTA. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- "Philadelphia Transit Plan | Office of Transportation, Infrastructure and Sustainability". City of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 2021-02-23. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- Office of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability (2021-02-22). "Philadelphia Transit Plan" (PDF). Philadelphia Transit Plan. pp. 122–131. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- Heller, Gregory L.; Garvin, Alexander (2013). Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0784-2.

- Treese, Lorett (2012). Railroads of Pennsylvania (2nd ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-81-170011-5.

- Vuchic, Vukan; Kikuchi, Shinya (1984). General Operations Plan for the SEPTA Regional High Speed System. Philadelphia: SEPTA.

- Vuchic, Vukan; Kikuchi, Shinya (1985). "Planning an Integrated Regional Rail Network: Philadelphia Case". Transportation Research Record (1036).

- Williams, Gerry (1998). Trains, Trolleys & Transit: A Guide to Philadelphia Area Rail Transit. Piscataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company. ISBN 978-0-9621541-7-1.