Racial politics in Brazil

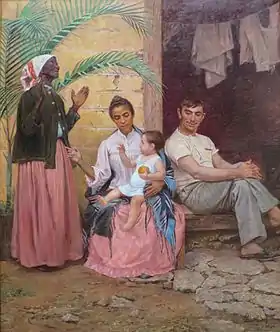

Racial whitening, or "whitening" (branqueamento), is an ideology that was widely accepted in Brazil between 1889 and 1914,[1] as the solution to the "Negro problem".[2][3] Whitening in Brazil is a sociological term to explain the change in perception of one's race, from darker to lighter identifiers, as a person rises in the class structure of Brazil.[4] Racial mixing in Brazilian society entailed that minority races ought to adopt the characteristics of the white race, with the goal of creating a singular Brazilian race that emulates the white race, striving to create a society best emulating that of Europe.[5]

Racial whitening became a social concept that was developed through governmental policy.[6] Similar to that of the United States, Brazil experienced colonization by Europeans and importation of African slaves in the 18th and 19th century.[6]

As a way of making Brazil seem like a modernized country comparable with European nations, Brazil encouraged the immigration of white Europeans with the goal of racial whitening through miscegenation. Once they arrived, European immigrants dominated high-skilled jobs, and libertos (freed slaves) were relegated to service or seasonal jobs. Additionally, whitening led to the formulation of the Brazilian idea of "racial democracy," the idea that Brazil lacks racial prejudice and discrimination, allowing equal opportunities for blacks and whites alike, effectively creating a race-blind society.[5]

The myth of racial democracy arose from the lack of a strict segregationist culture and the frequency of interracial marriage. Thus, it was argued that Brazil was not bound by racial lines, but issues caused by racism festered under the surface.[5] This inattention to race implied that all Brazilians had an equal opportunity to attain social mobility.[5]

However, this masked the true goal of whitening as a means to nullify the identities of black and indigenous identities. In Brazil, race is considered a spectrum upon which one’s identity is subject to change based on a variety of factors, such as social class and educational attainment.[6] Governmental policies like affirmative action seek to mediate identity problems associated with racial democracy.

Initial racial policies

Prior to the abolition of slavery, plantation owners feared a post-emancipatory society of freed slaves who had, "deficiencies such as indolence and immorality" that needed to be wiped out.[7] Brazil’s export based economy was largely reliant on slave labor, and slaveholders felt the freedmen would hinder the country’s development because of their inferior characteristics.[7] After the emancipation of slaves, Brazilians theorized about the ideal phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of future laborers. Initially, Brazil saw the success of Chinese immigrants in the U.S and other nations, but the risk of introducing another purportedly degenerate race like the Africans was too high. Arthur de Gobineau, a French diplomat sent to Brazil by Napoleon, felt introducing the Europeans was a perfect solution because it would purify elements of Brazil’s inferior race through interbreeding.[7] This solution would return the white race to their superior place. Brazilian writers and politicians blamed Portuguese colonials for importing a large slave population.[7]

Apart from its racial justification, Brazilian farmers argued that the post-emancipation labor market in Brazil would be controlled by supply and demand. Thus, incentivization of foreign immigrants would create a situation where laborers searched for employers at cheap prices instead of employers looking for a small pool of laborers at a high wage. This governmental stance is based upon three principles, which scholar Marcus Eugenio Oliveira Lima describes as "institutional relations towards ‘national eugenics;’ social perceptions and inter-group relations; and self-perception and interpersonal relations."[8]

Working with the São Paulo province, Brazil officially started incentivizing European immigration in 1884 when it created the semi-private Society for the Promotion of Immigration.[9] The program was, "responsible for informing European workers of employment opportunities available in São Paulo, paying their passage, overseeing their arrival in Brazil, and dispatching them to the coffee groves".[10] By 1895, the State Department of Agriculture had fully taken control of the operation because São Paulo province was officially transformed into a state. Until the abolition of slavery in 1888, Europeans were hesitant to emigrate away from their home countries because they believed that Brazilian farmers would treat them like slaves. After slavery’s abolishment in 1888, Brazil was flooded with European immigrants. Statistics demonstrate that, "compared to 195,000 immigrants who arrived in Brazil between 1870 and 1889, immigration between 1890 and 1909 totaled 1,100,000".[10] There was a constant decline in the Afro-Brazilian population between the censuses of 1872 and 1990, decreasing from 19.2% to under 5%, although the rate recovered to 6.2% at the 2000 census.[11] Once the European immigrants arrived in the late 19th century, most São Paulo immigrants worked as colonos (tenant farmers) which "received a fixed monetary income for maintaining a certain number of coffee trees plus a variable payment depending on the volume of the harvest".[10] Apart from São Paulo, there was no subsidized immigration program in Brazil. In these areas, the libertos’ experience varied: in Sergipe, vagrancy laws were implemented to force the free black population back onto the plantation, but some libertos stayed with their former employers or emigrated elsewhere.[10] However, Afro-Brazilians’ status improved with labor laws enacted during the great depression that required two thirds of businesses’ new hires to be Brazilian-born.[5]

The arrival of European immigrants created a two-tiered labor market where immigrants dominated factory, commerce, industrial, and artisanal jobs whereas Afro-Brazilians were relegated to seasonal or service jobs.[12] Freed slaves lacked the skill to compete with European immigrants in the technical jobs and preferred the variety of the service jobs. However, other historians like Florestan Fernandes attribute these labor market differences to a pre-emancipation mentality that avoided work during slavery and a lack of marketable skills to offer when the slaves were freed.[13] For employed Afro-Brazilians, they demanded better working conditions after emancipation, but European immigrants, especially Italians, accepted lower pay and harsher treatment to secure a higher social position.[14] Apart from their willingness, the source of the immigrants’ vulnerabilities in the labor force was two fold: Brazil was populated with low-skilled immigrants who didn’t have bargaining power with their employers, and most immigrants valued their spouse or child over joining a labor union that could get them fired. In one area of Brazil, "Eighty percent of the people who passed through the immigrant hostel in São Paulo city came as families".[15] In São Paulo, child-labor was common because of the little pay that their parents received.[16]

Contemporary Politics of Brazil

As a result of the whitening-induced interracial marriage in the late 19th century and a lack of segregation laws, race in modern Brazil is defined by the concept of "racial democracy." This inattention to race implies that all Brazilians have an equal opportunity to attain social mobility.[5]

Such identity problems and inequities caused by racial democracy led Afro-Brazilians to take measures to identify closer to the white race in order to place them on a level playing field. In a 1995 national survey, Brazilian citizens were asked to consistently classify race on an overall and contextual basis. This study found that persons of lighter color tended to be consistently classified, while those of a darker skin tone tended to be classified more ambiguously.[17] Factors that impacted consistency by 20% to 100% included education, age, sex, and local racial composition, trending in the direction of either "whitening" or "darkening."[17] To combat this, the Campanha Censo of 1990 sought to combat the trend of self-whitening, the false identification of oneself as white, in Brazil.[5]

Furthermore, there is a widespread difficulty in admitting that racism exists in Brazil. Because many don’t consciously identify as black, many instances of prejudice are not recognized as racism, which becomes a cycle, and racism continues to exist in Brazil. Moreover, Brazil almost prides itself as having somehow moved past racial discrimination because it was built on the mixing of Amerindian, African and European ethnic groups.[18] However, racism in Brazil exists and can take on a variety of forms of prejudices and stereotypes. In fact, a 2022 study on Racial Democracy and Black Victimization in Brazil finds that disparities in employment, income, education, access to justice, and vulnerability to violent death are heavily influenced by race, and in fact found that blacks are more exposed to homicides and physical assaults than whites, and 40% of this difference is evidence of racial discrimination.[19]

Employment disparities found in this study are supported by inadequate incentives for minority-owned businesses in Brazil, creating an every-man-for-himself survivalist environment for black business people.[20] This is consistent with the increase in workplace discrimination indicated by the Brazilian censuses of the 1960s and 70s, despite the passage of federal non-discrimination legislation in 1953.[5]

While black workers maintain sizeable numbers in the workforce, especially in small and midsize retailers and restaurants, they still struggle to break into high-paying corporate landscapes such as the accounting and tech industries.[17] Based on a recent survey, 94% of top executives in Brazil’s top corporations are white, which translates into minuscule opportunities for black Brazilians to gain the experience of going into business independently. In fact, non-whites make up 45.3% of the Brazilian population, yet they make up only 17.8% of all registered entrepreneurs.[21] Much of this has to deal with the educational and economic roots of many black businesspeople in the country. While black business leaders are younger, they have spent less time in the classroom than whites, with nearly half of all black leaders dropping out of school by the eighth grade and only 15.8% completing twelve years of schooling. This is in contrast to the 35.8% of white leaders who have completed twelve years of schooling.[21] Further evidence of the arduous path to black success in the private sector is the statistic that more than a third of black business leaders hail from poor rural or blue-collar urban families, compared to just a quarter of white business leaders. Such hardships within the business landscape for black Brazilians has led them to take measures to identify closer to the white race in order to place them on a level playing field.

An aspect that influences the upward mobility of individuals is education.[22] The education deficit between black and white entrepreneurs is better explained by a much higher illiteracy rate. In 1980, the number of illiterate black Brazilians was double that of whites, with blacks also being seven times less likely to graduate college.[5]

The Role of Affirmative Action

Several political, cultural, and social groups have emerged in Brazil in an attempt to gain equal rights and a positive Afro-Brazilian image for and among black Brazilians. This trend identifies blackness as a separate and significant identity, in contrast to it being traditionally erased. These initiatives have been implemented in the twenty-first century thanks to the adoption of affirmative action policies by a number of educational institutions and the federal government, which are meant to assist Afro-Brazilian students in obtaining a higher education and pursuing better opportunities similar to those available to Brazilians who are not black.[23]

The University of Brasilia (UnB), the first university in Brazil to implement a racial quota in 2004, served as the "guinea pig" for such initiatives. After the quota was implemented, UnB's white population fell by 4.3%, while mixed and black both grew by 1.4% and 3% respectively.[24] Therefore, a panel of Brazilian reviewers were employed for the semester both before and after the quota was put into effect. They were told to grade the subjects' skin tones on a scale of 1 (lightest) to 7 (darkest). The data indicates that after just one year of affirmative action at UnB, there is a noticeable increase in the number of black students or students who are generally of darker skin tone. In fact, a significant increase in the average skin tone indicates that the policy was successful in attracting more brown and black students to the university, particularly in the first semester following its introduction. The university's experiences with the policy and its consequences on the students, however, provide important information for the broader study of racial disparity in institutional settings for higher education and the workplace.

Although there is a blueprint, it is already evident that affirmative action has proven to be an uncomfortable fit for Brazil as a strategy for racial equality. Burnt white, brown, dark nut, light nut, black, and copper are just a few of the 136 categories the census department discovered Brazilians use for self-identification according to a 1976 research.[23] Almost 50 years later, today, Brazilians still regard themselves as falling across a spectrum of skin hues with a range of names. The realization that a person's appearance matters, particularly in terms of social mobility and job opportunities, is what ties these categories together. To address inequalities in higher education, the federal government established the Law of Social Quotas in 2012.[23] Regardless of color, the legislation guarantees public high school graduates half of all openings at institutions receiving federal funding. (Public universities, unlike high schools, are more prestigious in Brazil than private ones.) Half of those reserved seats go to students whose families make less than 1.5 minimum wage, or $443 per month, on average.[23] According to the proportion of white to non-white residents in each state, a share of the openings in both categories are therefore reserved for black, brown, and indigenous students. Despite the fact that this is trying to address certain racial challenges, it is actually causing brand-new ones. In 2014, a statute was passed by the federal government allocating 20% of public sector positions to people of color.[23] Where individuals don't cleanly fit into black-and-white classifications, it becomes difficult to label those eligible for affirmative action. "If you look at a photograph of the incoming medical class of 2015, only one of the students looks black," said Georgina Lima, a professor and head of UFPel’s Center for Affirmative Action and Diversity, "[a]nd he’s not even Brazilian. He’s from Africa.”[23] After it became obvious that the law allowed for fraud, the government instructed all departments to set up verification committees in August 2016.[23] However, it did not offer any guidance to the agencies. Verification committees attempt to fulfill this mandate mostly through checklists on physical appearance. Does the job applicant have a short, wide, and flat nose? How thick are their lips? Are their gums a deep enough purple color? Does their jaw protrude forward? Questions like these set up precise criteria. Some critics argued that these "desired" traits were too reminiscent of the slave trade, in which buyers would spin slaves around to look for specific traits. Others believed that these moves were regrettably essential to achieve true equity in Brazil.[23] But according to Rogerio Reis, chair of the committee at UFPel, people attempted to improve their chances at eligibility by presenting as blacker through, for example, style or tanning.[23] Tactics like these exemplify how the system is being taken advantage of. While racial whitening was pursued to create a unified Brazilian identity, the policy led to contemporary socioeconomic and political divides through racial democracy.

People who have made reference to whitening in Brazil

- João Batista de Lacerda: Director of the Museu Nacional, wrote a paper named "Half-Breeds of Brazil".[25] In it he describes the differences in the different races. He also predicted that by the third generation of mixed breeding there are predominantly white characteristics.

- Theodore Roosevelt: After visiting Brazil in 1913 he wrote an article in Outlook magazine. In his article he talks about how the Brazilian Negro is disappearing.[26]

- Thomas Skidmore: Wrote the book Black into White which covers many of the aspects dealing with Whitening. Also gives his own theories and insights.

- Samuel Alexson: Wrote a pamphlet in New York explaining whitening to the common man.[27]

References

- Sánchez Arteaga, Juanma. "Biological Discourses on Human Races and Scientific Racism in Brazil (1832–1911)." Journal of the History of Biology 50.2 (2017): 267-314.

- Skidmore, Thomas. Black Into White: Race and Nationality in Brazilian Thought, Oxford University Press. NY, 1974.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. (2011). Predictions are always deceptive: João Baptista de Lacerda and his white Brazil. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, 18(1), 225-242

- NOGUEIRA, Oracy. "Tanto preto quanto branco: estudo de relações raciais no Brasil." São Paulo: TA Queiróz, Série 1 (1985).

- Creighton, Helen (May 2008). "How Far is the 'Rhetoric of Inclusion; Reality of Exclusion' Argument Applicable to the Relationship of Afro-Latin Americans to the Nation-State?". History Compass. 6 (3): 843–854. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2008.00532.x.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz (March 2011). "Fontes". História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos. 18 (1): 225–242. doi:10.1590/s0104-59702011000100013. ISSN 0104-5970. PMID 21552698.

- Aidoo, Lamonte (13 November 2018). "Genealogies of horror: three stories of slave-women, motherhood, and murder in the Americas". African and Black Diaspora. 13 (1): 40–53. doi:10.1080/17528631.2018.1541959. ISSN 1752-8631. S2CID 149902604.

- Lima, Marcus Eugênio Oliveira (December 2007). "Review Essay: Racial Relations and Racism in Brazil: Telles, Edward Eric, Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil. Princeton, NJ/Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006. 324 pp. ISBN 978—0—691—12792—7 (pbk)". Culture & Psychology. 13 (4): 461–473. doi:10.1177/1354067X07082805. ISSN 1354-067X. S2CID 146389827.

- Andrews, George Reid (August 1988). "Black and White Workers: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1928". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 68 (3): 491–524. doi:10.2307/2516517. JSTOR 2516517.

- Bértola, Luis; Williamson, Jeffrey, eds. (2017). Has Latin American Inequality Changed Direction?. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44621-9. ISBN 978-3-319-44620-2.

- Lima, Marcus Eugênio Oliveira (December 2007). "Review Essay: Racial Relations and Racism in Brazil". Culture & Psychology. 13 (4): 461–473. doi:10.1177/1354067x07082805. ISSN 1354-067X. S2CID 146389827.

- Andrews, George Reid (August 1988). "Black and White Workers: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1928". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 68 (3): 491–524. doi:10.2307/2516517. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2516517.

- Andrews, George Reid (August 1988). "Black and White Workers: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1928". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 68 (3): 491–524. doi:10.2307/2516517. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2516517.

- Andrews, George Reid (August 1988). "Black and White Workers: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1928". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 68 (3): 491–524. doi:10.2307/2516517. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2516517.

- Andrews, George Reid (August 1988). "Black and White Workers: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1928". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 68 (3): 491–524. doi:10.2307/2516517. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2516517.

- Andrews, George Reid (August 1988). "Black and White Workers: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1928". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 68 (3): 491–524. doi:10.2307/2516517. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2516517.

- Telles, Edward E. (January 2002). "Racial ambiguity among the Brazilian population". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 25 (3): 415–441. doi:10.1080/01419870252932133. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 51807734.

- "Climate and Culture Beyond Borders". British Art Studies (18). doi:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-18/worm/p4.

- Truzzi, Bruno; Lirio, Viviani S.; Cerqueira, Daniel R. C.; Coelho, Danilo S. C.; Cardoso, Leonardo C. B. (February 2022). "Racial Democracy and Black Victimization in Brazil". Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 38 (1): 13–33. doi:10.1177/10439862211038448. ISSN 1043-9862. S2CID 238728755.

- Recco, Ianna. "In the Flesh at the Heart of Empire: Life-Likeness in Wax Representations of the 1762 Cherokee Delegation in London". British Art Studies (21). doi:10.17658/issn.2058-5462. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- Figueiredo, Angela (18 February 2002). ""The End of 'Social Whitening'."". Newsweek International.

- Arteaga, Juanma Sánchez (23 May 2016). "Biological Discourses on Human Races and Scientific Racism in Brazil (1832–1911)". Journal of the History of Biology. 50 (2): 267–314. doi:10.1007/s10739-016-9445-8. ISSN 0022-5010. PMID 27216739. S2CID 254551700.

- Cleuci de Oliveira, "Brazil's New Problem with Blackness," Foreign Policy, 5 April 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/05/brazils-new-problem-with-blackness-affirmative-action/ .

- Lewis, Marissa (2022). Evidence-Based Best Practice for Discharge Planning: A Policy Review (Thesis). University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences Library. doi:10.46409/sr.qbwh5074.

- "The Metis, or Half-Breeds, of Brazil" (PDF).

Children of metis have been found, in the third generation, to present all the physical characters of the white race, although some of them retain a few traces of their black ancestry through the influence of atavism. The influence of sexual selection, however, tends to neutralise that of atavism, and removes from the descendants of the metis all the characteristic features of the black race. In virtue of this process of ethnic reduction, it is logical to expect that in the course of another century the metis will have disappeared from Brazil.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Roosevelt, Theodore (21 February 1914). "Brazil and the Negro". Outlook. New York: Outlook Publishing Company, Incorporated.

- Alexson, Samuel. On the Whitening of the Brazilian Negro, Nonsensical Press. NY, 1967.