R v Adams (1957)

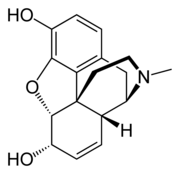

R v Adams [1957] is an English case that established the principle of double effect applicable to doctors: that if a doctor "gave treatment to a seriously ill patient with the aim of relieving pain or distress, as a result of which that person's life was inadvertently shortened, the doctor was not guilty of murder" where a restoration to health is no longer possible. Such medicines are among those sometimes used in palliative care (the branch of medicine focussed on the relief of pain), most commonly for the most severe pain.

| R v John Bodkin Adams | |

|---|---|

Morphine, as in the case, is often prescribed in a relatively high dose to those in most severe, chronic pain, and high doses and cumulation of such opioids accelerates dying (including the stronger drug heroin, also used in the case) | |

| Court | Crown Court (specifically sitting at the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey)) |

| Full case name | Regina v. John Bodkin Adams |

| Decided | 8 April 1957 |

| Citation(s) | [1957] Crim LR 365 |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | none |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Devlin J. |

| Case opinions | |

| Decision by | Jury |

| Keywords | |

| palliative care, principle of double effect as to care by doctors, ease of suffering, murder, euthanasia | |

| Criminal law |

|---|

| Elements |

| Scope of criminal liability |

| Severity of offense |

|

| Inchoate offenses |

| Offense against the person |

| Sexual offenses |

| Crimes against property |

| Crimes against justice |

| Crimes against the public |

|

| Crimes against animals |

| Crimes against the state |

| Defenses to liability |

| Other common-law areas |

| Portals |

The case narrowly distinguished and approved the binding precedent R v Dyson[1] which confirms it is no defence, in itself, in offences of homicide, that the victim was already dying from an illness if the defendant's conduct has accelerated death. Doctors have an absolute defence to this where they have "properly" eased the suffering of the patient.

Case facts

The defendant, John Bodkin Adams, was a doctor who was tried on one count of murder by "easing the passing" of an elderly patient, Mrs Edith Alice Morrell. The police claimed that Adams had murdered a number of elderly patients, and suggested his modus operandi was to administer heroin and morphine with the intention making his patients addicted and under his influence, then to induce them to leave him legacies in cash or kind in their wills and finally to cause their deaths by giving them sufficiently large doses of drugs. One patient's initial bequest included an elderly Rolls-Royce car, she re-decided to leave Adams nothing in her final will. The trial judge, Devlin J., suggested that Hannam had become fixated on the idea that Adams had murdered (or administered excess drugs) to many elderly patients for legacies, and had regarded Adams receiving a legacy as grounds for suspicion.[2] Hannam's team investigated the wills of 132 of Adams' former patients dating between 1946 and 1956 where he had benefited from a legacy, and prepared a short list with around a dozen names for submission to the prosecuting authorities.[3] The list included Morrell, Mrs Gertrude Hullett and two other cases in which evidence had been taken on oath,[4] Devlin considered that Morrell's death, which was chosen by the Attorney-General for prosecution, looked the strongest of Hannam's preferred cases, despite it being six years old, although he noted that some others believed that the Hullett case was stronger.[5]

Trial

The case presented by the prosecution was based on the police investigation. As outlined in the opening speech of the Attorney-General Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller, it was that Adams either administered or instructed others to administer drugs that had killed Morrell with the intention of killing her, that these drugs were unnecessary as she was not suffering pain as she had been semi-comatose for some time before her death. Manningham-Buller suggested that the motive for Adams deciding that it was time for Morrell to die was that he feared her altering her will to his disadvantage.[6] Strictly in the English law of murder, the prosecution did not need to show a motive but, if it did not, it needed to prove the offence by demonstrating precisely how the killing was carried out.[7] Throughout the trial, the prosecution maintained that the motive was a mercenary one; Manningham-Buller did not say that Adams had a primary intention to kill (to euthanise), from his phraseology of the intention of "easing the passing" – according to the trial judge.[8]

The prosecution initially argued that all of the large quantities of morphia and heroin prescribed by Adams in the months leading to Morrell's death had been injected, that this amount was sufficient to kill her, and that it could only have been intended to kill.[9] Adams was accused of murdering Morell by one of two methods, singly or in combination. The first alleged method was as the cumulative result of the amounts of opiates given in the ten months before her death,[10] the second was as the result of two large injections of an unknown, but presumed to be lethal, substance prepared by Adams and injected into Morrell shortly before her death.[11] However, on the second day of the trial, the defence produced nurses' notebooks, which showed that smaller quantities of drugs had been given to the patient than the prosecution had estimated, based on Adams' prescriptions. These notebooks also recorded that the two injections made the night before her death as consisting of paraldehyde, described as a safe soporific.[12]

In response to the defence's production of the nurses' notebooks, one of the prosecution's medical expert witnesses changed his testimony,[13] Dr Douthwaite had introduced a new theory on how Morrell had been killed, which was not accepted by his fellow sworn-in expert, nor the defence's medical expert witness.[14] The prosecution's only riposte was to argue that the nurses' records were incomplete, and the judge commented that, by this point, a conviction seemed to him unlikely because the medical evidence was inconclusive[15]

Judgment

In Devlin's summing up, was said that a doctor has no special defence, but "he is entitled to do all that is proper and necessary to relieve pain even if the measures he takes may incidentally shorten life" (i.e. as a secondary intention). He made one legal direction that established the double effect principle in respect of the mens rea of murder. Where restoring a patient to health is no longer possible, a doctor may lawfully give treatment with the aim of relieving pain and suffering which, as an unintentional result, shortens life. Liability for murder can be avoided if medicine which is beneficial to the patient is given, despite the knowledge that death will occur as a side effect. The second legal direction was that the jury should not conclude that any more drugs were administered to Morrell than shown in the nurses' notebooks.[16]

Devlin also indicated to the jury the main defence argument was that the whole case against Dr. Adams was mere suspicion and that, "...the case for the defence seems to me to be a manifestly strong one".

On these grounds, the jury returned a Not Guilty verdict after deliberating for only forty-six minutes.[17]

Outside the courtroom he opined that the majority of those that had followed the case in The Times law reports expected an acquittal.

It is worth noting the mens rea for murder is governed by the doctrine of intent, set out in the Woollin case, where a defendant is held to have intended the outcome if it is virtually certain and the defendant has appreciated that virtual certainty.[18] Applying this test would create liability in R v Adams but it did not for the legal excuse provided for by the doctrine of double effect.

See also

- English law

- Airedale NHS Trust v Bland - approving the case in the highest court, and adding further principles.

Notes

- R v Dyson [1908] KB 454, 1 Cr App Rep 13, 72 JP 303, 77 LJKB 813, 21 Cox CC 669, All ER Rep 736, 52 Sol Jo 535, 99 LT 201, 24 TLR 653

- Devlin, p. 181.

- Devlin, pp. 18–19.

- Devlin, pp. 24–5.

- Devlin, pp. 11, 25.

- Devlin, pp. 2–5.

- Devlin, pp. 69, 123.

- Devlin, p. 163.

- Devlin, pp. x, 4–5

- Devlin, pp. 51–2.

- Devlin, pp. 5–6, 51.

- Devlin, pp. 65, 81, 85.

- Devlin, pp. 118–20.

- Devlin, pp. 119, 126–7.

- Devlin, pp. 129–30, 150.

- Devlin, pp. 171–2.

- Devlin, pp. 176–9.

- [1999] 1 A.C. 82

Sources

- P. Devlin, (1985). Easing the passing: The trial of Doctor John Bodkin Adams. London, The Bodley Head.ISBN 0-57113-993-0.

External links

- Bailii.org, a free online database for English and Irish legal materials.