Quercus pungens

Quercus pungens, commonly known as the sandpaper oak or scrub oak, is a North American species evergreen or sub-evergreen shrub or small tree in the white oak group. There is one recognised variety, Quercus pungens var. vaseyana, the Vasey shin oak.[3] Sandpaper oak hybridizes with gray oak (Quercus grisea) in the Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico and Texas.[4]

| Quercus pungens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Quercus |

| Subgenus: | Quercus subg. Quercus |

| Section: | Quercus sect. Quercus |

| Species: | Q. pungens |

| Binomial name | |

| Quercus pungens | |

| |

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Description

The sandpaper oak can be a small tree of up to 12 metres (39 feet) high or a large shrub that forms thickets. The bark is light brown and papery. The twigs are gray, with short velvety hairs, becoming smooth with age. The buds are dark red-brown, sparsely covered with hairs. The leathery leaves are semi-evergreen, being bright glossy green at first but turning darker with age. It is their rough texture, caused by minute persistent hair bases, that gives the tree its name of sandpaper oak. The inflorescence, which appears in spring, is reddish, the female catkins having one to three flowers and the male catkins numerous flowers. The acorn cups are shallow and covered with dense gray hairs. The acorns grow singly or in pairs and are light brown, broadly ovoid with a rounded apex.[3][5]

Distribution and habitat

Sandpaper and Vasey shin oaks are abundant in the Edwards Plateau and the Trans-Pecos region of Texas. They also occur in the Guadalupe Mountains and westward to the mountains of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, and in northern and eastern Mexico (Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, Nuevo León, and Veracruz).[3][6][7]

The preferred habitat of these oaks is on dry limestone or igneous slopes at a height of 800–2,000 m (2,600–6,600 ft) above sea level, in chaparral and desert scrub savanna, usually in communities of oak, juniper and pinyon pine.[3]

Ecology

In the chaparral formations in the Guadalupe Mountains, it is one of the dominant species and is found growing alongside true mountain-mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus) and desert ceanothus (Ceanothus greggii). Other plants associated with it include the Mohr shin oak (Quercus mohriana), oneseed juniper (Juniperus monosperma), cane cholla (Opuntia imbricata), purplefruited pricklypear (Opuntia phaeacantha), Mexican buckeye (Ungnadia speciosa), Texas persimmon (Diospyros texana), hairy tridens (Erioneuron pilosum) and plateau oak (Quercus fusiformis).[8]

References

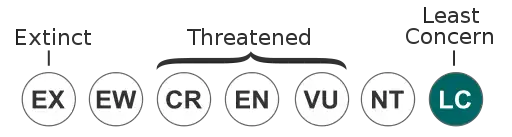

- Kenny, L.; Wenzell , K. (2015). "Quercus pungens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T72420426A72420469. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T72420426A72420469.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Quercus pungens Liebm.". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – via The Plant List. Note that this website has been superseded by World Flora Online

- Pavek, Diane S. (1993). "Quercus pungens". Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service (USFS), Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory.

- Gehlbach, Frederick R. 1967. Vegetation of the Guadalupe Escarpment, New Mexico-Texas. Ecology. 48(3): 404-419.

- Nixon, Kevin C. (1997). "Quercus pungens". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 3. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- "Quercus pungens". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2014.

- SEINet, Southwestern Biodiversity, Arizona chapter

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 1992. Plant communities of Texas (Series level): February 1992. Austin, TX: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Texas Natural Heritage Program. 38 p.