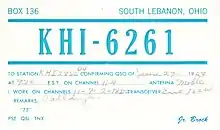

QSL card

A QSL card is a written confirmation of either a two-way radiocommunication between two amateur radio or citizens band stations; a one-way reception of a signal from an AM radio, FM radio, television or shortwave broadcasting station; or the reception of a two-way radiocommunication by a third party listener. A typical QSL card is the same size and made from the same material as a typical postcard, and most are sent through the mail as such.

QSL card derived its name from the Q code "QSL". A Q code message can stand for a statement or a question (when the code is followed by a question mark). In this case, 'QSL?' (note the question mark) means "Do you confirm receipt of my transmission?" while 'QSL' (without a question mark) means "I confirm receipt of your transmission."[1]

History

During the early days of radio broadcasting, the ability for a radio set to receive distant signals was a source of pride for many consumers and hobbyists. Listeners would mail "reception reports" to radio broadcasting stations in hopes of getting a written letter to officially verify they had heard a distant station. As the volume of reception reports increased, stations took to sending post cards containing a brief form that acknowledged reception. Collecting these cards became popular with radio listeners in the 1920s and 1930s, and reception reports were often used by early broadcasters to gauge the effectiveness of their transmissions.[2]

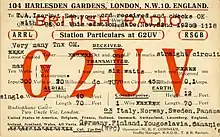

The concept of sending a post card to verify reception of a station (and later two-way contact between them) may have been independently invented several times. The earliest reference seems to be a card sent in 1916 from 8VX in Buffalo, New York to 3TQ in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (in those days ITU prefixes were not used). The standardized card with callsign, frequency, date, etc. may have been developed in 1919 by C.D. Hoffman, 8UX, in Akron, Ohio. In Europe, W.E.F. "Bill" Corsham, 2UV, first used a QSL when operating from Harlesden, England in 1922.[3]

Use in amateur radio

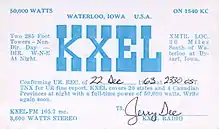

Amateur radio operators exchange QSL cards to confirm two-way radio contact between stations. Each card contains details about one or more contacts, the station and its operator. At a minimum, this includes the call sign of both stations participating in the contact, the time and date when it occurred (usually specified in UTC), the radio frequency or band used, the mode of transmission used, and a signal report.[4] The International Amateur Radio Union and its member societies recommend a maximum size of 3+1⁄2 by 5+1⁄2 inches (90 by 140 mm).[5]

Although some QSL cards are plain, they are a ham radio operator's calling card and are therefore frequently used for the expression of individual creativity — from a photo of the operator at their station to original artwork, images of the operator's home town or surrounding countryside, etc. Consequently, the collecting of QSL cards with especially interesting designs has become a frequent addition to the simple gathering of printed documentation of a ham's communications over the course of his or her radio career.

Normally sent using ordinary, international postal systems, QSL cards can be sent either direct to an individual's address, or via a country's centralized amateur radio association QSL bureau, which collects and distributes cards for that country. This saves postage fees for the sender by sending several cards destined for a single country in one envelope, or large numbers of cards using parcel services. Although this reduces postage costs, it increases the delivery time because of the extra handling time involved.[6] In addition to such incoming bureaus, there are also outgoing bureaus in some countries. These bureaus offer further postage savings by accepting cards destined for many different countries and repackaging them together into bundles that are sent to specific incoming bureaus.[7] Most QSL bureaus operated by national amateur radio societies are both incoming and outgoing, with the exception of the United States of America, and are coordinated by the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU).[7]

For rare countries, that is, ones where there are very few amateur radio operators, places with no reliable (or even existing) postal systems, including expeditions to remote areas, a volunteer QSL manager may handle the mailing of cards. For expeditions this may amount to thousands of cards, and payment for at least postage is appreciated, and is required for a direct reply (as opposed to a return via a bureau).

The Internet has enabled electronic notification as an alternative to mailing a physical card. These systems use computer databases to store the same information normally verified by QSL cards, in an electronic format. Some sponsors of amateur radio operating awards, which normally accept QSL cards for proof of contacts, may also recognize a specific electronic QSL system in verifying award applications.

- One such system, called eQSL,[8] enables electronic exchange of QSLs as JPEG or GIF images which can then be printed as cards on the recipient's local inkjet or laser printer, or displayed on the computer monitor. Many logging programs now have direct electronic interfaces to transmit QSO details in real-time into the eQSL.cc database. CQ Amateur Radio magazine began accepting electronic QSLs from eQSL.cc for its four award programs in January 2009. 10-10 has been accepting eQSLs since 2002.

- Another system, the ARRL’s Logbook of The World (LoTW), allows confirmations to be submitted electronically for that organization’s DX Century Club and Worked All States awards. Confirmations are in the form of database records, electronically signed with the private key of the sender. This system simply matches database records but does not allow creation of pictorial QSL cards.

Despite the advantages of electronic QSLs, physical QSL cards are often historical or sentimental keepsakes of a memorable location heard or worked, or of a pleasant contact with a new radio friend, and serious ham radio operators may have thousands of them. Some cards are plain, while others are multicolored and may be oversized or double paged.

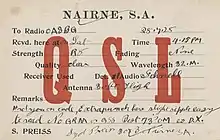

Usage in shortwave listening

International shortwave broadcasters have traditionally issued QSL cards to listeners to verify reception of programming, and also as a means of judging the size of their audiences, effective reception distances, and technical performance of their transmitters. QSL cards can also serve as publicity tools for the shortwave broadcaster, and sometimes the cards will include cultural information about the country.[9]

The High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program has occasionally requested reception information on its shortwave experiments, in return for which it sent back QSL cards.[10] Standard frequency and time stations, such as WWV, will also send QSL cards in response to listeners reports. Other shortwave utility stations, such as marine and aviation weather broadcasters, may QSL, as do some pirate radio stations, usually through mail drop boxes.

Usage in CB radio

CB radio enthusiasts often exchanged colorful QSL cards, especially during the height of CB's popularity in the 1970s.[11] CB radio operators who met while on the air would typically swap personalized QSL cards which featured their names ("handles") and CB callsigns.[12] Originally, CB required a purchased license and the use of a callsign; however, when the CB craze was at its peak many people ignored this requirement and invented their own "handles".[13]

A simple card format might only include the users callsign and/or "handle", home location, and note the date and time of a CB radio contact. More elaborate cards featured caricatures, cartoons, slogans and jokes, sometimes of a ribald nature.[12] As the CB radio fad grew in the U.S. and Canada, a number of artists specializing in artwork for CB QSL cards emerged.[14]

Usage in TV-FM and AM DXing

QSL cards are also collected by radio enthusiasts who listen for distant FM radio or TV stations. With the advent of digital broadcasting there is greater difficulty with the reception of weak TV signals due to the cliff effect,[15] however AM broadcasting radio stations will often reply to listener reports, particularly if they report receiving them at a significant distance.[16]

See also

- DXing

- Heys Collection, a collection of QSL cards in the British Library Philatelic Collections

Further reading

- Gregory, Danny; Paul Sahre (2003). Hello World: A Life in Ham Radio. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1-56898-281-X.

- Kenyon, Ronald W. QSL: How I Traveled the World and Never Left Home. Kindle Direct Publishing (2020). ISBN 9798686214170. 163 pages. Color illustrations of 109 vintage QSL cards from 1956 to 1961 issued by 89 shortwave stations in 75 countries, 35 cards from radio amateurs and shortwave monitors, and 13 holiday greeting cards from shortwave stations in nine countries. Introduction and Appendix: 'A Letter from Antarctica.'

References

- ICAO PANS-ABC Doc8400, International Civil Aviation Organization; full list reproduced at Ralf D. Kloth (31 December 2009). "List of Q-codes". Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Timothy D. Taylor; Mark Katz; Tony Grajeda (19 June 2012). Music, Sound, and Technology in America: A Documentary History of Early Phonograph, Cinema, and Radio. Duke University Press. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-0-8223-4946-4. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Who invented the QSL Card? Archived July 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Ellen White, W1YL, ed. (1976). ARRL Ham Radio Operating Guide. Newington, CT: American Radio Relay League. p. 55.

- Eckersley, R. J, G4FTJ (1985). Amateur Radio Operating Manual (3 ed.). Potters Bar, Herts, UK: Radio Society of Great Britain. p. 32. ISBN 0-900612-69-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Radio Amateur's Handbook 1978. Newington, CT: American Radio Relay League. 1977. p. 653.

- "IARU QSL Bureaus". 2009-02-02. Archived from the original on 2020-01-08. Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- http://www.eqsl.cc/qslcard/ Archived 2022-05-02 at the Wayback Machine : eQSL home page

- Jerome S. Berg (1 October 2008). Listening on the Short Waves, 1945 to Today. McFarland. pp. 330–. ISBN 978-0-7864-5199-9. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- A HAARP QSL card Archived 2016-03-31 at the Wayback Machine for the 40 meter moonbounce experiment in January 2008

- Mark Menjivar (9 June 2015). The Luck Archive: Exploring Belief, Superstition, and Tradition. Trinity University Press. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-1-59534-250-8. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Tukker, Paul. "American collector finds trove of Yukon CB radio memorabilia". CBC News. CBC. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- MotorBoating. November 1975. pp. 16–. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- Smith, Jordan (21 November 2015). "CB Radio QSL Cards: A 1970s Social Media Craze". Flashbak.com. Alum Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Lars-Ingemar Lundstrom (21 August 2012). Understanding Digital Television: An Introduction to DVB Systems with Satellite, Cable, Broadband and Terrestrial TV Distribution. CRC Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-1-136-03282-0. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- Barun Roy (1 September 2009). Enter The World Of Mass Media. Pustak Mahal. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-81-223-1080-1.

External links

- Historical data on the early QSLs

- SWL QSL Card Museum

- American Radio Relay League Logbook of the World

- American Radio Relay League QSL Buruea

- A very large QSL gallery, more than 12,000 old cards (French, machine translation into English available)

- Electronic QSL Card Centre

- EuroBureauQSL: the EURAO's QSL Bureaus Global Network

- Martin Elbe's QSL-Pages, a QSL collection of broadcasting stations

- What information and where to print QSL cards, by Thierry, ON4SKY

- Ham Gallery QSL Museum, a collection of QSL cards from around the world

- a QSL collection of broadcasting stations

- SARL Electronic QSL service

- QSL Cards from the Past list of over 40,000 cards with over 2200 scanned cards on display including one from a young Coast Guard Sailor named Arthur M. Godfrey dated 1929.

- Arquivo Portugues de QSL Portuguese QSL Archive

- QSL Museum

- Ukrainian DX QSL Trophies - QSL Gallery by US7IID - More than 11.600 QSL cards of amateur radio stations.

- The Final Courtesy: A QSL Card 77 Years in the Making A long-delayed QSL card is recreated and sent

- The Committee to Preserve Radio Verifications

- The QSL card - key points for today & vintage card gallery

- WNYC QSL cards.

- George L. Glotzbach QSL collection at the University of Maryland libraries.