Pythagorean trigonometric identity

The Pythagorean trigonometric identity, also called simply the Pythagorean identity, is an identity expressing the Pythagorean theorem in terms of trigonometric functions. Along with the sum-of-angles formulae, it is one of the basic relations between the sine and cosine functions.

The identity is

As usual, means .

Proofs and their relationships to the Pythagorean theorem

Proof based on right-angle triangles

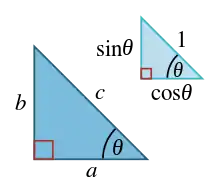

Any similar triangles have the property that if we select the same angle in all of them, the ratio of the two sides defining the angle is the same regardless of which similar triangle is selected, regardless of its actual size: the ratios depend upon the three angles, not the lengths of the sides. Thus for either of the similar right triangles in the figure, the ratio of its horizontal side to its hypotenuse is the same, namely cos θ.

The elementary definitions of the sine and cosine functions in terms of the sides of a right triangle are:

The Pythagorean identity follows by squaring both definitions above, and adding; the left-hand side of the identity then becomes

which by the Pythagorean theorem is equal to 1. This definition is valid for all angles, due to the definition of defining and for the unit circle and thus and for a circle of radius c and reflecting our triangle in the y axis and setting and .

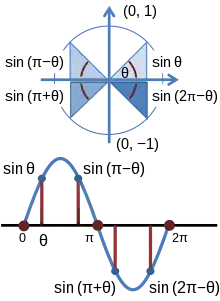

Alternatively, the identities found at Trigonometric symmetry, shifts, and periodicity may be employed. By the periodicity identities we can say if the formula is true for −π < θ ≤ π then it is true for all real θ. Next we prove the identity in the range π/2 < θ ≤ π, to do this we let t = θ − π/2, t will now be in the range 0 < t ≤ π/2. We can then make use of squared versions of some basic shift identities (squaring conveniently removes the minus signs):

All that remains is to prove it for −π < θ < 0; this can be done by squaring the symmetry identities to get

Related identities

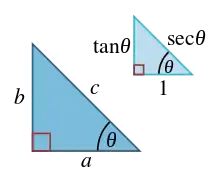

The identities

and

are also called Pythagorean trigonometric identities.[1] If one leg of a right triangle has length 1, then the tangent of the angle adjacent to that leg is the length of the other leg, and the secant of the angle is the length of the hypotenuse.

and:

In this way, this trigonometric identity involving the tangent and the secant follows from the Pythagorean theorem. The angle opposite the leg of length 1 (this angle can be labeled φ = π/2 − θ) has cotangent equal to the length of the other leg, and cosecant equal to the length of the hypotenuse. In that way, this trigonometric identity involving the cotangent and the cosecant also follows from the Pythagorean theorem.

The following table gives the identities with the factor or divisor that relates them to the main identity.

| Original Identity | Divisor | Divisor Equation | Derived Identity | Derived Identity (Alternate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

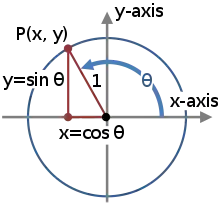

Proof using the unit circle

The unit circle centered at the origin in the Euclidean plane is defined by the equation:[2]

Given an angle θ, there is a unique point P on the unit circle at an anticlockwise angle of θ from the x-axis, and the x- and y-coordinates of P are:[3]

Consequently, from the equation for the unit circle:

the Pythagorean identity.

In the figure, the point P has a negative x-coordinate, and is appropriately given by x = cos θ, which is a negative number: cos θ = −cos(π−θ). Point P has a positive y-coordinate, and sin θ = sin(π−θ) > 0. As θ increases from zero to the full circle θ = 2π, the sine and cosine change signs in the various quadrants to keep x and y with the correct signs. The figure shows how the sign of the sine function varies as the angle changes quadrant.

Because the x- and y-axes are perpendicular, this Pythagorean identity is equivalent to the Pythagorean theorem for triangles with hypotenuse of length 1 (which is in turn equivalent to the full Pythagorean theorem by applying a similar-triangles argument). See Unit circle for a short explanation.

Proof using power series

The trigonometric functions may also be defined using power series, namely (for x an angle measured in radians):[4][5]

Using the multiplication formula for power series at Multiplication and division of power series (suitably modified to account for the form of the series here) we obtain

In the expression for sin2, n must be at least 1, while in the expression for cos2, the constant term is equal to 1. The remaining terms of their sum are (with common factors removed)

by the binomial theorem. Consequently,

which is the Pythagorean trigonometric identity.

When the trigonometric functions are defined in this way, the identity in combination with the Pythagorean theorem shows that these power series parameterize the unit circle, which we used in the previous section. This definition constructs the sine and cosine functions in a rigorous fashion and proves that they are differentiable, so that in fact it subsumes the previous two.

Proof using the differential equation

Sine and cosine can be defined as the two solutions to the differential equation:[6]

satisfying respectively y(0) = 0, y′(0) = 1 and y(0) = 1, y′(0) = 0. It follows from the theory of ordinary differential equations that the first solution, sine, has the second, cosine, as its derivative, and it follows from this that the derivative of cosine is the negative of the sine. The identity is equivalent to the assertion that the function

is constant and equal to 1. Differentiating using the chain rule gives:

so z is constant. A calculation confirms that z(0) = 1, and z is a constant so z = 1 for all x, so the Pythagorean identity is established.

A similar proof can be completed using power series as above to establish that the sine has as its derivative the cosine, and the cosine has as its derivative the negative sine. In fact, the definitions by ordinary differential equation and by power series lead to similar derivations of most identities.

This proof of the identity has no direct connection with Euclid's demonstration of the Pythagorean theorem.

Proof using Euler's formula

Using Euler's formula and factoring as the complex difference of two squares,

See also

Notes

- Lawrence S. Leff (2005). PreCalculus the Easy Way (7th ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 296. ISBN 0-7641-2892-2.

- This result can be found using the distance formula for the distance from the origin to the point . See Cynthia Y. Young (2009). Algebra and Trigonometry (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-470-22273-7. This approach assumes Pythagoras' theorem. Alternatively, one could simply substitute values and determine that the graph is a circle.

- Thomas W. Hungerford, Douglas J. Shaw (2008). "§6.2 The sine, cosine and tangent functions". Contemporary Precalculus: A Graphing Approach (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-495-10833-7.

- James Douglas Hamilton (1994). "Power series". Time series analysis. Princeton University Press. p. 714. ISBN 0-691-04289-6.

- Steven George Krantz (2005). "Definition 10.3". Real analysis and foundations (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 269–270. ISBN 1-58488-483-5.

- Tyn Myint U., Lokenath Debnath (2007). "Example 8.12.1". Linear partial differential equations for scientists and engineers (4th ed.). Springer. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-8176-4393-5.