Puerto Hondo stream salamander

The Puerto Hondo stream salamander or Michoacan stream salamander (Ambystoma ordinarium) is a mole salamander from the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt within the Mexican state of Michoacán.[2]

| Puerto Hondo stream salamander | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Ambystomatidae |

| Genus: | Ambystoma |

| Species: | A. ordinarium |

| Binomial name | |

| Ambystoma ordinarium Taylor, 1940 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ambystoma ordinaria Taylor, 1940 "1939" | |

Distribution and habitat

A. ordinarium is only found at Puerto Hondo, in a small stream four miles west of El Mirador, and at Puerto Garnica, in another small stream nearby with dark, cold waters and a temperature of 12.4 °C. These streams are high in the mountains, at elevations of 9000 and 9400 feet above sea level, respectively. Larvae and neotenes have been found swimming against the current of the streams, at depths of 5–12 in. Terrestrial adults remain near stream banks, and are often found side-by-side with gilled adults, but can also be found under debris in pine and fir forests up to 30 m away from streams.[3]

Description

A. ordinarium larvae and neonates have sparse, evenly distributed melanophores and rows of light silver-yellow specks. Larvae have well-developed fins, small but bushy gills, and 16–24 gill rakers (average, 18.8) on their third gill arches. Larvae reach a maximum size of 100 mm snout-to-vent length (SVL) and 191 mm total length.[4][5]

At sexual maturity, these salamanders measure between 70 and 75 mm SVL. Terrestrial adults reach a maximum size of 86 mm SVL. They have narrow heads, and 16–24 tooth-rakers on their third gill arches. Adults generally have uniform dark or black coloring on their backs, but some may be mottled, and others may retain larval coloration.[5][6]

Lifecycle, activity, and diet

A. ordinarium specimens live about two years.[7]

The salamander has a prolonged breeding season and may breed throughout the year.[5] An average of 109 eggs are laid alone or in clusters of two to five on the undersides of root, branches, and rocks, hanging free in the current. Eggs are pigmented, measure 9.9 mm, and are encased in three capsules, including a thick outer capsule.[5]

New hatchlings have fully developed fins, and both larvae and adults walk on the bottom more than they swim.[5]

They are diurnal, hiding under cover of stream bank or under log early in the day and come out by late morning [5]

Terrestrial prey includes grasshoppers, ants, leafhoppers, scuds, earthworms, and nematodes. Aquatic prey includes aquatic insect larvae, such as caddisfly larvae, small aquatic beetles, and clams.[3][8]

Threat and status

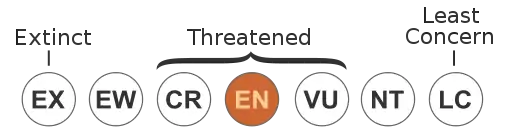

A. ordinarium is able to live in cleared pastures and watering holes, so the decline of forests does not pose an immediate threat. Fragmentation of their habitats due to human development and the desiccation of streams is the biggest threat to the species, which is protected in Mexico.[3][9]

Classification controversy

This species has been suggested to be the same species as the Lake Patzcuaro salamander, Ambystoma dumerilii, based on genetic analysis, but their habitats have been isolated for 7–10 million years [10] A. dumerilii is also wholly neotenic, while A. ordinarium is variable but mostly terrestrial.

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2020). "Ambystoma ordinarium". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T59066A161153310. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T59066A161153310.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2015). "Ambystoma ordinarium Taylor, 1940". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Alavarado-Diaz, J., Garcia-Garrido, P., and Suazo-Ortuño, I. (2002). Food Habits of a Paedomorphic Population of the Mexican Salamander, Ambystoma ordinarium (Caudata: Ambystomatidae). The Southwestern Naturalist, 28(1), 100-102. cited at

- Anderson, J. D. (1975). Ambystoma ordinarium. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, 164.1-164.2.

- Anderson, J. D., and Worthington, R. D. (1971). The life history of the Mexican salamander Ambystoma ordinarium Taylor. Herpetologica, 27, 165-176.cited at

- Shaffer, H. B. (1984). Evolution in a paedomorphic lineage. II. Size and shape in the Mexican ambystomatid salamanders. Evolution, 38, 1194-1206.cited at

- J.K., 1975. Longevity of reptiles and amphibians in N. American collections as of 1 November, 1975. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Miscellaneous Publications, Herpetological Circular 6:1-32.

- Duellman, W. E. (1961). The amphibians and reptiles of Michoacán, México. University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History, 15, 1-148.cited at

- IUCN, Conservation International, and NatureServe. 2006. Global Amphibian Assessment: Agalychnis annae. www.globalamphibians.org. Accessed on 19 October 2007.cited at

- Brandon, R.A., "Natural History of the Axolotl." In Developmental Biology of the Axolotl., Ed. J.B. Armstrong and G.M Malacinski. Oxford University Press, 1989.