Provinces of Sweden

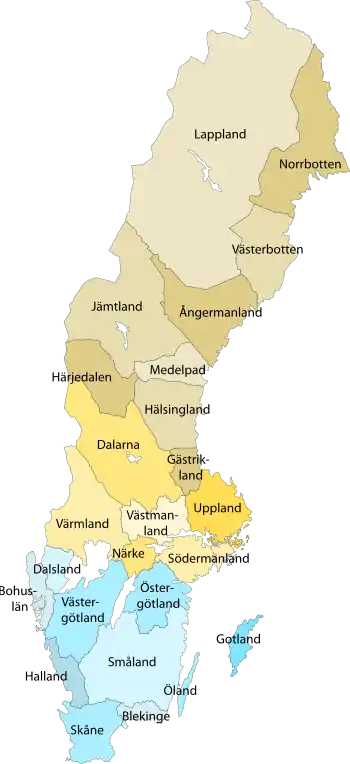

The provinces of Sweden (Swedish: Sveriges landskap) are historical, geographical and cultural regions. Sweden has 25 provinces; they have no administrative function (except for in some cases as sport districts), but remain historical legacies and a means of cultural identification as pertains, for example, to dialects and folklore.

.png.webp)

Several of them were subdivisions of Sweden until 1634, when they were replaced by the counties of Sweden (län). Some were conquered later on from Denmark–Norway. Others, like the provinces of Finland, were lost.

In some cases, the administrative counties correspond almost exactly to the provinces, as is Blekinge to Blekinge County and Gotland, which is a province, county and a municipality. While not exactly corresponding with the province, Härjedalen Municipality is beside Gotland the only municipality named after a province. In other cases, the county borders do not correspond with the older provincial ones, which enhances the cultural importance of the provinces. In addition, the administrative units are continually subject to change — several new counties for instance were created in the 1990s — while the historical provincial borders have remained stable for centuries. All the provinces are also ceremonial duchies, but as such have no administrative or political functions.

The provinces of Sweden are still used in colloquial speech and cultural references, and therefore cannot be regarded as an archaic concept. The main exception is Lapland where the population see themselves as a part of Västerbotten or Norrbotten, based on the counties.

Particular to Stockholm and Gothenburg is the fact that both cities have provincial borders going through them: Stockholm is split between Uppland and Södermanland, whereas Gothenburg is split between Västergötland and Bohuslän. According to a 2011 GfK survey, inhabitants in the big cities — Stockholm, Gothenburg and, to a lesser extent, Malmö — identify primarily with their city, rather than with the province they live in.[2]

Provinces

| Swedish | Latin |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ångermanland | Angermannia | |

| Blekinge | Blechingia | |

| Bohuslän | Bahusia | |

| Dalarna | Dalecarlia | |

| Dalsland | Dalia | |

| Gästrikland | Gestricia | |

| Gotland | Gotlandia | |

| Halland | Hallandia | |

| Hälsingland | Helsingia | |

| Härjedalen | Herdalia | |

| Jämtland | Jemtia | |

| Lappland | Lapponia Suecana | |

| Medelpad | Medelpadia | |

| Närke | Nericia | |

| Norrbotten | Norbothnia | |

| Öland | Olandia | |

| Östergötland | Ostrogothia | |

| Skåne | Scania | |

| Småland | Smolandia | |

| Södermanland | Sudermannia | |

| Uppland | Uplandia | |

| Värmland | Wermlandia | |

| Västerbotten | Westrobothnia | |

| Västergötland | Westrogothia | |

| Västmanland | Westmannia |

English and other languages occasionally use Latin names as alternatives to the Swedish names. The name Scania for Skåne predominates in English. Some purely English exonyms, such as the Dales for Dalarna, East Gothland for Östergötland, Swedish Lapland for Lappland and West Bothnia for Västerbotten (and corresponding forms) are common in English literature.[3][4][5] Swedes writing in English have long used Swedish-language name forms only.[6][7]

History

The origins of the provincial divisions lay in the petty kingdoms that gradually became more and more subjected to the rule of the Kings of Sweden during the consolidation of Sweden. Until the country law of Magnus Ericson in 1350, each of these lands still had its own laws with its own assembly (the thing), and in effect governed themselves. The historical provinces were considered duchies, but newly conquered provinces added to the kingdom either received the status of a duchy or a county, depending on their individual importance.

After the separation from the Kalmar Union in 1523 the Kingdom incorporated only some of its new conquests as provinces. The most permanent acquisitions stemmed from the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658, in which the former Danish Scanian lands – the provinces of Skåne, Blekinge, Halland and Gotland – along with the Norwegian Bohuslän, Jämtland and Härjedalen, became Swedish and gradually integrated. Other foreign territories were ruled as Swedish Dominions under the Swedish monarch, in some cases for two or three centuries. Norway, in personal union with Sweden from 1814 to 1905, never became an integral part of Sweden.

The division of Västerbotten that took place with the cession of Finland caused Norrbotten to emerge as a county, and eventually to be recognized as a province in its own right. It was granted a coat of arms as late as in 1995.

Some scholars suggest that Sweden revived the province concept in the 19th century.[8]

The lands of Sweden

Historically, Sweden was seen as containing four "lands" (larger regions):

- Götaland (southern Sweden)

- Svealand (central Sweden)

- Österland (Finland, from the 13th Century to 1809)

- Norrland (northern parts of present-day Sweden and north-western Finland)

In the Viking Age and earlier, Götaland and Svealand consisted of a number of petty kingdoms that were more or less independent; Götaland in the Iron Age and Middle Ages did not include Scania and other provinces in the far south which were part of Denmark. The leading tribe of Götaland in the Iron Age was the Geats; the main tribe of Svealand, according to Tacitus ca 100 AD, was the Suiones (or the "historical Swedes"). "Norrland" was the overall denomination for all of the unexplored northern parts, the outward boundaries of which and control by the Swedish king were weakly defined into the early modern age.

Due to the Northern Crusades against Finns, Tavastians and Karelians and colonisation of some coastal areas of the country, Finland fell under the Catholic Church and Swedish rule. Österland ("Eastern land"; the name had early gone out of use) in southern and central Finland formed an integral part of Sweden. In 1809 Finland was annexed by Russia, reunited with some frontier counties annexed several decades earlier to form the Grand Duchy of Finland, and becoming in 1917 the independent country of Finland.

The borders of these regions have changed several times throughout history, adapting to changes in national borders, and Norrland, Svealand and Götaland are only parts of Sweden and have never superseded the concept of the provinces.

Heraldry

At the funeral of King Gustav Vasa (Gustav I) in 1560 some early versions of coats of arms for 23 of the provinces listed below were displayed together for the first time, most of them having been created for that particular occasion. Erik XIV of Sweden modeled the funeral processions for Gustav Vasa on the continental renaissance funerals of influential German dukes, who in turn may have styled their display of power on Charles V's funeral procession, where flags were used to represent each entry in the long list of titles of the dead. Having only three flags as a representation of the entities Svealand, Götaland and Wends mentioned in Vasa's title, "King of Sweden, the Goths and the Wends", would have been diminutive in comparison with the pompous displays of ducal power on the continent, so flags were promptly created to represent each of the provinces. At the funeral of Charles X Gustav more flags were added to the procession, namely the coats of arms for Estonia, Livonia, Ingria, Narva, Pomerania, Bremen and Verden, as well as coat of arms for the German territories Kleve, Sponheim, Jülich, Ravensberg and Bayern.

Since most of the historical Swedish provinces did not have set coats of arms at the time of Gustav Vasa's death, they were promptly created and granted. However, some of the coats of arms designed for the occasion were short-lived, such as the beaver picked to represent Medelpad, the wolverine in the coat of arms for Värmland and the rose-adorned coat of arms for Småland. Östergötland was for the occasion represented by two coats of arms, one with a Västanstång dragon and one with a Östanstång lion. The current coat of arms for Östergötland, listed below, was created in 1884. The savage representing Lappland was not used in King Gustav's procession, but was adopted as a coat of arms at the funeral procession of Charles IX in 1612, where the savage was initially black. The current coat of arms for Lappland, with a red, club-carrying man, was created in 1949. The list of coats of arms appearing below is thus different from the funeral procession flags, and consists of more recent inventions, many created during a period of romantic nationalism in the 19th century.

After the separation of Sweden and Finland the traditions for respective provincial arms diverged, most noticeably following an order by the King in Council on 18 January 1884. This established that all Swedish provinces carry ducal coronets, while the Finnish provincial arms still discriminated between ducal and county status. A complication was that the representation of Finnish ducal and county coronets resembled Swedish coronets of a lower order, namely county and baronial. The division of Lapland necessitated a distinction between the Swedish and the Finnish arms.

For more information, see Lands of Sweden or articles on the individual lands or provinces.

Götaland

Götaland (Gothia, Gothenland) consists of ten historical provinces located in the southern part of Sweden. Until 1645 Gotland and Halland were parts of Denmark. Furthermore, until 1658 Blekinge and Scania were parts of Denmark and Bohuslän part of Norway.

Svealand

Svealand (Swealand) consists of the following six provinces in middle Sweden. Until 1812 Värmland was a part of Götaland.

Norrland

Norrland (Northland) consists today of nine provinces in northern and central Sweden. Until 1645 the provinces of Jämtland and Härjedalen were parts of Norway. Swedish Lapland was united with Finnish Lapland as Lapland until 1809. Norrbotten was separated from Västerbotten and developed as a province of its own during the 19th century.

See also

References

- "Folkmängd i landskapen den 31 december 2016" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- GfK Sverige AB. "Svenskarna är mer lokala än nationella i sin geografiska identitet". Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Eric Linklater in The Life of Charles XII

- Robert Nisbet Bain in Gustavus III and His Contemporaries

- Bernard Quaritch in The stories of the Kings of Norway Called the Round World (Heimskringla)

- R. Svanström & C.F. Palmstierna in A History of Sweden (1934)

- Nils Ahnlund in Gustav Adolf the Great (1940)

- Jacobsson, Benny (2000). "Konstruktion av landskap. Exemplet Uppland" Archived 2 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Idéhistoriska perspektiv. Ed. Ingemar Nilsson, Arachne 16, Göteborg 2000, p. 109-119. Retrieved 20 October 2006. (In Swedish).