Duchy of Anjou

The Duchy of Anjou (UK: /ˈɒ̃ʒuː, ˈæ̃ʒuː/, US: /ɒ̃ˈʒuː, ˈæn(d)ʒuː, ˈɑːnʒuː/;[1][2][3] French: [ɑ̃ʒu] ⓘ; Latin: Andegavia) was a French province straddling the lower Loire. Its capital was Angers, and its area was roughly co-extensive with the diocese of Angers. Anjou was bordered by Brittany to the west, Maine to the north, Touraine to the east and Poitou to the south. The adjectival form is Angevin, and inhabitants of Anjou are known as Angevins. In 1482, the duchy became part of the Kingdom of France and then remained a province of the Kingdom under the name of the Duchy of Anjou. After the decree dividing France into departments in 1790, the province was disestablished and split into six new départements: Deux-Sèvres, Indre-et-Loire, Loire-Atlantique, Maine-et-Loire, Sarthe and Vienne.

| Duchy of Anjou Duché d'Anjou | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1360–1482 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Capital | Angers | ||||||||

| Demonym | Angevin, Angevins, Angevine, Angevines | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Duchy | ||||||||

| King of France | |||||||||

• 1360–1380 | Charles V | ||||||||

• 1461–1482 | Louis XI | ||||||||

| Duke of Anjou | |||||||||

• 1360–1384 | Louis I of Anjou | ||||||||

• 1480–1481 | Charles IV of Anjou | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• County of Anjou raised to Duchy | 1360 | ||||||||

• Integrated into Kingdom of France | 1482 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Duchy of Anjou

The county of Anjou was united to the royal domain between 1205 and 1246, when it was turned into an apanage for the king's brother, Charles I of Anjou. This second Angevin dynasty, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, established itself on the throne of Naples and Hungary. Anjou itself was united to the royal domain again in 1328, but was detached in 1360 as the Duchy of Anjou for the king's son, Louis I of Anjou. The third Angevin dynasty, a branch of the House of Valois, also ruled for a time the Kingdom of Naples. The dukes had the same autonomy as the earlier counts, but the duchy was increasingly administered in the same fashion as the royal domain and the royal government often exercised the ducal power while the dukes were away.

On 17 February 1332, Philip VI bestowed it on his son John the Good, who, when he became king in turn (22 August 1350), gave the countship to his second son Louis I, raising it to a duchy in the peerage of France by letters patent of 25 October 1360. Louis I, who became in time count of Provence and titular king of Naples, died in 1384, and was succeeded by his son Louis II, who devoted most of his energies to his Neapolitan ambitions, and left the administration of Anjou almost entirely in the hands of his wife, Yolande of Aragon. On his death (29 April 1417), she took upon herself the guardianship of their young son Louis III, and, in her capacity of regent, defended the duchy against the English. Louis III, who also devoted himself to winning Naples, died on 15 November 1434, leaving no children. The duchy of Anjou then passed to his brother René, second son of Louis II and Yolande of Aragon.[4]

Province of Anjou

| Province of Anjou Province of Anjou | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1482–1790 | |||||||||||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||||||

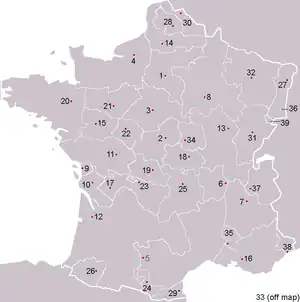

.png.webp) Location of Anjou and Saumurois within the Kingdom of France in 1789 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Angers | ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym | Angevin, Angevins, Angevine, Angevines | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Type | Province | ||||||||||||||||||

| King of France | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1482 – 1483 | Louis XI | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1774 – 1792 | Louis XVI | ||||||||||||||||||

| Duke of Anjou | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1515 – 1531 | Louise of Savoy | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1755 – 1795 | Louis Stanislas Xavier de Bourbon | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages / Early Modern | ||||||||||||||||||

• Integrated into Kingdom of France | 1482 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Decree dividing France into departments | 1790 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Unlike his predecessors, who had rarely stayed long in Anjou, René from 1443 onwards paid long visits to it, and his court at Angers became one of the most brilliant in the kingdom of France. But after the sudden death of his son John in December 1470, René, for reasons which are not altogether clear, decided to move his residence to Provence and leave Anjou for good. After making an inventory of all his possessions, he left the duchy in October 1471, taking with him the most valuable of his treasures. On 22 July 1474 he drew up a will by which he divided the succession between his grandson René II of Lorraine and his nephew Charles II, count of Maine. On hearing this, King Louis XI, who was the son of one of King René's sisters, seeing that his expectations were thus completely frustrated, seized the duchy of Anjou. He did not keep it very long, but became reconciled to René in 1476 and restored it to him, on condition, probably, that René should bequeath it to him. However that may be, on the death of the latter (10 July 1480) he again added Anjou to the royal domain.[4]

Later, King Francis I again gave the duchy as an appanage to his mother, Louise of Savoy, by letters patent of 4 February 1515. On her death, in September 1531, the duchy returned into the king's possession. In 1552 it was given as an appanage by Henry II to his son Henry of Valois, who, on becoming king in 1574, with the title of Henry III, conceded it to his brother Francis, duke of Alençon, at the treaty of Beaulieu near Loches (6 May 1576). Francis died on 10 June 1584, and the vacant appanage definitively became part of the royal domain.[4]

Government

At first Anjou was included in the gouvernement (or military command) of Orléanais, but in the 17th century was made into a separate one. Saumur, however, and the Saumurois, for which King Henry IV had in 1589 created an independent military governor-generalship in favour of Duplessis-Mornay, continued till the Revolution to form a separate gouvernement, which included, besides Anjou, portions of Poitou and Mirebalais. Attached to the généralité (administrative circumscription) of Tours, Anjou on the eve of the Revolution comprised five êlections (judicial districts):--Angers, Baugé, Saumur, Château-Gontier, Montreuil-Bellay and part of the êlections of La Flèche and Richelieu. Financially it formed part of the so-called pays de grande gabelle, and comprised sixteen special tribunals, or greniers à sel (salt warehouses):--Angers, Baugé, Beaufort, Bourgueil, Candé, Château-Gontier, Cholet, Craon, La Flèche, Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, Ingrandes, Le Lude, Pouancé, Saint-Rémy-la-Varenne, Richelieu, Saumur. From the point of view of purely judicial administration, Anjou was subject to the parlement of Paris; Angers was the seat of a presidial court, of which the jurisdiction comprised the sénéchaussées of Angers, Saumur, Beaugé, Beaufort and the duchy of Richelieu; there were besides presidial courts at Château-Gontier and La Flèche. When the Constituent Assembly, on 26 February 1790, decreed the division of France into departments, Anjou and the Saumurois, with the exception of certain territories, formed the department of Maine-et-Loire, as at present constituted.[4]

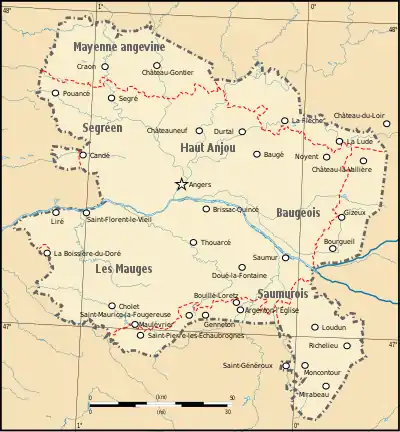

Under the kingdom of France, Anjou was practically identical with the diocese of Angers, bound on the north by Maine, on the east by Touraine, on the south by Poitou (Poitiers) and the Mauges, and the west by the countship of Nantes or the duchy of Brittany.[5][4] Traditionally Anjou was divided into four natural regions: the Baugeois, the Haut-Anjou (or Segréen), the Mauges, and the Saumurois.

It occupied the greater part of what is now the department of Maine-et-Loire. On the north, it further included Craon, Candé, Bazouges (Château-Gontier), Le Lude; on the east, it further added Château-la-Vallière and Bourgueil; while to the south, it lacked the towns of Montreuil-Bellay, Vihiers, Cholet, and Beaupréau, as well as the district lying to the west of the Ironne and Thouet on the left bank of the Loire, which formed the territory of the Mauges.[4]

Region of Anjou

Since the end of the provincial system in 1790, the name of 'Anjou' has been used to describe the former region in which the duchy and province occupied. This region roughly correlates to several regions: Mayenne angevine (north west), Haut Anjou (centre-northern), Segreen (western), Baugeois (eastern), Les Mauges (south western), and Saumurois (south).

Gallery

References

- "Anjou". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Anjou" (US) and "Anjou". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020.

- "Anjou". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Halphen 1911.

- Baynes 1878.

Sources

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 58

- Collins, Paul, The Birth of the West: Rome, Germany, France, and the Creation of Europe in the Tenth Century.

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Halphen, Louis (1911), "Anjou", in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–58

Further reading

- The chronicles of Normandy by William of Poitiers and of Jumièges and Ordericus Vitalis (in Latin)

- The chronicles of Maine, particularly the Actus pontificum cenomannis in urbe degentium (in Latin)

- The Gesta consulum Andegavorum (in Latin)

- Chroniques des comtes d'Anjou, published by Marchegay and Salmon, with an introduction by E. Mabille, Paris, 1856–1871 (in French)

- Louis Helphen, Êtude sur les chroniques des comtes d'Anjou et des seigneurs d'Amboise (Paris, 1906) (in French)

- Louis Helphen, Recueil d'annales angevines et vendómoises (Paris, 1903) (in French)

- Auguste Molinier, Les Sources de l'histoire de France (Paris, 1902), ii. 1276–1310 (in French)

- Louis Helphen, Le Comté d'Anjou au XIe siècle (Paris, 1906) (in French)

- Kate Norgate, England under the Angevin Kings (2 vols., London, 1887)

- A. Lecoy de La Marche, Le Roi René (2 vols., Paris, 1875). (in French)

- Célestin Port, Dictionnaire historique, géographique et biographique de Maine-et-Loire (3 vols., Paris and Angers, 1874–1878) (in French)

- idem, Préliminaires. (in French)

- Edward Augustus Freeman, The History of the Norman Conquest of England, its Causes and its Results (2d vol.)

- Luc d'Achery, Spicilegium, sive Collectio veterum aliquot scriptorum qui in Galliae bibliothecis, maxime Benedictinorum, latuerunt (in Latin)