Protestant Bible

A Protestant Bible is a Christian Bible whose translation or revision was produced by Protestant Christians. Typically translated into a vernacular language, such Bibles comprise 39 books of the Old Testament (according to the Hebrew Bible canon, known especially to non-Protestant Christians as the protocanonical books) and 27 books of the New Testament, for a total of 66 books.[2] Some Protestants use Bibles which also include 14 additional books in a section known as the Apocrypha (though these are not considered canonical) bringing the total to 80 books.[3][4] This is in contrast with the 73 books of the Catholic Bible, which includes seven deuterocanonical books as a part of the Old Testament.[5] The division between protocanonical and deuterocanonical books is not accepted by all Protestants who simply view books as being canonical or not and therefore classify books found in the Deuterocanon, along with other books, as part of the Apocrypha.[6] Sometimes the term "Protestant Bible" is simply used as a shorthand for a bible which contains only the 66 books of the Old and New Testaments.

It was in Luther's Bible of 1534 that the Apocrypha was first published as a separate intertestamental section.[7] Early modern English bibles also generally contained an Apocrypha section but in the years following the first publication of the King James Bible in 1611, printed English bibles increasingly omitted the Apocrypha. However, to this date, the Apocrypha is "included in the lectionaries of Anglican and Lutheran Churches."[8]

The practice of including only the Old and New Testament books within printed bibles was standardized among many English-speaking Protestants following a 1825 decision by the British and Foreign Bible Society.[9] Today, "English Bibles with the Apocrypha are becoming more popular again" and they may be printed as intertestamental books.[10] In contrast, Evangelicals vary among themselves in their attitude to and interest in the Apocrypha but agree in the view that it is non-canonical.[11]

Early Protestant Bibles

.djvu.jpg.webp)

The first proto-Protestant Bible translation was Wycliffe's Bible, that appeared in the late 14th century in the vernacular Middle English. Wycliffe's writings greatly influenced the philosophy and teaching of the Czech proto-Reformer Jan Hus (c. 1369–1415).[12] The Hussite Bible was translated into Hungarian by two Hussite priests, Tamás Pécsi and Bálint Újlaki, who studied in Prague and were influenced by Jan Hus. They started writing the Hussite Bible after they returned to Hungary and finalized it around 1416.[13] However, the translation was suppressed by the Catholic Inquisition. It was not until the 16th century that translated Bibles became widely available. The full New Testament was translated into Hungarian by János Sylvester in 1541. In 1590 a Calvinist minister, Gáspár Károli, produced the first printed complete Bible in Hungarian, the Vizsoly Bible.

One of the central events in the development of the Protestant Bible canon was the publication of Luther's translation of the Bible into High German (the New Testament was published in 1522; the Old Testament was published in parts and completed in 1534).[1] Following the Protestant Reformation, Protestants Confessions have usually excluded the books which other Christian traditions consider to be deuterocanonical books from the biblical canon (the canon of the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox churches differs among themselves as well),[14] most early Protestant Bibles published the Apocrypha along with the Old Testament and New Testament.

The German-language Luther Bible of 1534 did include the Apocrypha. However, unlike in previous Catholic Bibles which interspersed the deuterocanonical books throughout the Old Testament, Martin Luther placed the Apocrypha in a separate section after the Old Testament, setting a precedent for the placement of these books in Protestant Bibles. The books of the Apocrypha were not listed in the table of contents of Luther's 1532 Old Testament and, in accordance with Luther's view of the canon, they were given the well-known title: "Apocrypha: These Books Are Not Held Equal to the Scriptures, but Are Useful and Good to Read" in the 1534 edition of his Bible translation into German.[15]

In the English language, the incomplete Tyndale Bible published in 1525, 1534, and 1536, contained the entire New Testament. Of the Old Testament, although William Tyndale translated around half of its books, only the Pentateuch and the Book of Jonah were published. Viewing the canon as comprising the Old and New Testaments only, Tyndale did not translate any of the Apocrypha.[16] However, the first complete Modern English translation of the Bible, the Coverdale Bible of 1535, did include the Apocrypha. Like Luther, Miles Coverdale placed the Apocrypha in a separate section after the Old Testament.[17] Other early Protestant Bibles such as the Matthew's Bible (1537), Great Bible (1539), Geneva Bible (published by Sir Rowland Hill[18] in 1560), Bishop's Bible (1568), and the King James Version (1611) included the Old Testament, Apocrypha, and New Testament.[10] Although within the same printed bibles, it was usually to be found in a separate section under the heading of Apocrypha and sometimes carrying a statement to the effect that the such books were non-canonical but useful for reading.[19]

Protestant translations into Italian were made by Antonio Brucioli in 1530, by Massimo Teofilo in 1552 and by Giovanni Diodati in 1607. Diodati was a Calvinist theologian and he was the first translator of the Bible into Italian from Hebrew and Greek sources. Diodati's version is the reference version for Italian Protestantism. This edition was revised in 1641, 1712, 1744, 1819 and 1821. A revised edition in modern Italian, Nuova Diodati, was published in 1991.

Several translations of Luther's Bible were made into Dutch. The first complete Dutch Bible was printed in Antwerp in 1526 by Jacob van Liesvelt.[20] However, the translations of Luther's Bible had Lutheran influences in their interpretation. At the Calvinistic Synod of Dort in 1618/19, it was therefore deemed necessary to have a new translation accurately based on the original languages. The synod requested the States-General of the Netherlands to commission it. The result was the Statenvertaling or States Translation which was completed in 1635 and authorized by the States-General in 1637. From that year until 1657, a half-million copies were printed. It remained authoritative in Dutch Protestant churches well into the 20th century.

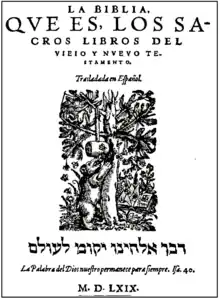

Protestant translations into Spanish began with the work of Casiodoro de Reina, a former Catholic monk, who became a Lutheran theologian.[21] With the help of several collaborators,[22] de Reina produced the Biblia del Oso or Bear Bible, the first complete Bible printed in Spanish based on Hebrew and Greek sources. Earlier Spanish translations, such as the 13th-century Alfonsina Bible, translated from Jerome's Vulgate, had been copied by hand. The Bear Bible was first published on 28 September 1569, in Basel, Switzerland.[23][24] The deuterocanonical books were included within the Old Testament in the 1569 edition. In 1602 Cipriano de Valera, a student of de Reina, published a revision of the Bear Bible which was printed in Amsterdam in which the deuterocanonical books were placed in a section between the Old and New Testaments called the Apocrypha.[25] This translation, subsequently revised, came to be known as the Reina-Valera Bible.

The first Protestant translations of portions of the Bible into Welsh were made in the 16th century with the Gospels and Epistles being published in 1551. In 1567, the entirety of the New Testament along with the Psalms were published in Welsh, while William Morgan translated the first version of the whole Bible into Welsh from Greek and Hebrew in 1588.

For the following three centuries, most English language Protestant Bibles, including the Authorized Version, continued with the practice of placing the Apocrypha in a separate section after the Old Testament. However, there were some exceptions. A surviving quarto edition of the Great Bible, produced some time after 1549, does not contain the Apocrypha although most copies of the Great Bible did. A 1575 quarto edition of the Bishop's Bible also does not contain them. Subsequently, some copies of the 1599 and 1640 editions of the Geneva Bible were also printed without them.[26] The Anglican King James VI and I, the sponsor of the Authorized King James Version (1611), "threatened anyone who dared to print the Bible without the Apocrypha with heavy fines and a year in jail."[4]

The Souldiers Pocket Bible, of 1643, draws verses largely from the Geneva Bible but only from either the Old or New Testaments. In 1644 the Long Parliament forbade the reading of the Apocrypha in churches and in 1666 the first editions of the King James Bible without the Apocrypha were bound.[27] Similarly, in 1782–83 when the first English Bible was printed in America, it did not contain the Apocrypha and, more generally, English Bibles came increasingly to omit the Apocrypha.[10]

19th-century developments

In 1826,[28] the National Bible Society of Scotland petitioned the British and Foreign Bible Society not to print the Apocrypha,[29] resulting in a decision that no BFBS funds were to pay for printing any Apocryphal books anywhere. They reasoned that by not printing the secondary material of Apocrypha within the Bible, the scriptures would prove to be less costly to produce.[30][31] The precise form of the resolution was:

That the funds of the Society be applied to the printing and circulation of the Canonical Books of Scripture, to the exclusion of those Books and parts of Books usually termed Apocryphal[32]

Similarly, in 1827, the American Bible Society determined that no bibles issued from their depository should contain the Apocrypha.[33]

Current situation

Since the 19th century changes, many modern editions of the Bible and re-printings of the King James Version of the Bible that are used especially by non-Anglican Protestants omit the Apocrypha section. Additionally, modern non-Catholic re-printings of the Clementine Vulgate commonly omit the Apocrypha section. Many re-printings of older versions of the Bible now omit the apocrypha and many newer translations and revisions have never included them at all. Sometimes the term "Protestant Bible" is used as a shorthand for a bible which only contains the 66 books of the Old and New Testaments.[34]

Although bibles with an Apocrypha section remain rare in protestant churches,[35] more generally English Bibles with the Apocrypha are becoming more popular than they were and they may be printed as intertestamental books.[10] Evangelicals vary among themselves in their attitude to and interest in the Apocrypha. Some view it as a useful historical and theological background to the events of the New Testament while others either have little interest in the Apocrypha or view it with hostility. However, all agree in the view that it is non-canonical.[36]

Books

Protestant Bibles comprise 39 books of the Old Testament (according to the Jewish Hebrew Bible canon, known especially to non-Protestants as the protocanonical books) and the 27 books of the New Testament for a total of 66 books. Some Protestant Bibles, such as the original King James Version, include 14 additional books known as the Apocrypha, though these are not considered canonical.[3] With the Old Testament, Apocrypha, and New Testament, the total number of books in the Protestant Bible becomes 80.[4] Many modern Protestant Bibles print only the Old Testament and New Testament;[30] there is a 400-year intertestamental period in the chronology of the Christian scriptures between the Old and New Testaments. This period is also known as the "400 Silent Years" because it is believed to have been a span where God made no additional canonical revelations to his people.[37]

These Old Testament, Apocrypha and New Testament books of the Bible, with their commonly accepted names among the Protestant Churches, are given below. Note that "1", "2", or "3" as a leading numeral is normally pronounced in the United States as the ordinal number, thus "First Samuel" for "1 Samuel".[38]

Old Testament

- Book of Genesis

- Book of Exodus

- Book of Leviticus

- Book of Numbers

- Book of Deuteronomy

- Book of Joshua

- Book of Judges

- Book of Ruth

- Books of Samuel

- Books of Kings

- Books of Chronicles

- Book of Ezra

- Book of Nehemiah

- Book of Esther

- Book of Job

- Psalms

- Book of Proverbs

- Ecclesiastes

- Song of Songs

- Book of Isaiah

- Book of Jeremiah

- Book of Lamentations

- Book of Ezekiel

- Book of Daniel

- Book of Hosea

- Book of Joel

- Book of Amos

- Book of Obadiah

- Book of Jonah

- Book of Micah

- Book of Nahum

- Book of Habakkuk

- Book of Zephaniah

- Book of Haggai

- Book of Zechariah

- Book of Malachi

Apocrypha (not used in all churches or bibles)

- 1 Esdras (3 Esdras Vulgate)

- 2 Esdras (4 Esdras Vulgate)

- Tobit

- Judith ("Judeth" in Geneva)

- Rest of Esther

- Wisdom of Solomon

- Ecclesiasticus (also known as Sirach)

- Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah ("Jeremiah" in Geneva)

- The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children

- Susanna

- Bel and the Dragon

- Prayer of Manasses

- 1 Maccabees

- 2 Maccabees

- 3 Maccabees

- 4 Maccabees

- Psalm 151

New Testament

- Gospel of Matthew

- Gospel of Mark

- Gospel of Luke

- Gospel of John

- Acts of the Apostles

- Epistle to the Romans

- First Epistle to the Corinthians

- Second Epistle to the Corinthians

- Epistle to the Galatians

- Epistle to the Ephesians

- Epistle to the Philippians

- Epistle to the Colossians

- First Epistle to the Thessalonians

- Second Epistle to the Thessalonians

- First Epistle to Timothy

- Second Epistle to Timothy

- Epistle to Titus

- Epistle to Philemon

- Epistle to the Hebrews

- Epistle of James

- First Epistle of Peter

- Second Epistle of Peter

- First Epistle of John

- Second Epistle of John

- Third Epistle of John

- Epistle of Jude

- Book of Revelation

Notable English translations

Most Bible translations into English conform to the Protestant canon and ordering while some offer multiple versions (Protestant, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox) with different canon and ordering. For example, the version of the ESV with Apocrypha has been approved as a Catholic bible.[39]

Most Reformation-era translations of the New Testament are based on the Textus Receptus while many translations of the New Testament produced since 1900 rely upon the eclectic and critical Alexandrian text-type.

Notable English translations include:

| Abbreviation | Name | Date | With Apocrypha? | Translation | Textual basis principal sources indicated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WYC | Wycliffe's Bible | 1382 - 1395 | Yes | Formal equivalence | Jerome's Latin Vulgate |

| TYN | Tyndale Bible | 1526 (NT), 1530 (Pentateuch), 1531 (Jonah) | No | Formal equivalence | Pent. & Jon: Hebrew Bible or Polyglot Bible with reference to Luther's translation[40] NT: Erasmus's Novum Instrumentum omne |

| TCB | Coverdale Bible | 1535 | Yes | Formal equivalence | Tyndale Bible, Luther Bible, Zürich Bible and the Vulgate |

| Matthew Bible | 1537 | Yes | Formal equivalence | Tyndale Bible, Coverdale Bible | |

| GEN | Geneva Bible | 1557 (NT), 1560 (OT) | Usually | Formal equivalence | OT: Hebrew Bible NT: Textus Receptus |

| KJV or AV | King James Version (aka "Authorized Version") | 1611, 1769 (Blayney revision) | Varies | Formal equivalence | OT: Bomberg's Hebrew Rabbinic Bible Apoc.: Septuagint NT: Beza's Greek New Testament |

| YLT | Young's Literal Translation | 1862 | No | Extreme formal equivalence | OT: Masoretic text NT: Textus Receptus |

| DBY | Darby Bible | 1867 (NT) OT+NT (1890) | No | Formal equivalence | |

| RV | Revised Version (or English Revised Version) | 1881 (NT), 1885 (OT) | Version available from 1894 | Formal equivalence | |

| ASV | American Standard Version | 1900 (NT), 1901 (OT) | No | Formal equivalence | NT: Westcott and Hort 1881 and Tregelles 1857, (Reproduced in a single, continuous, form in Palmer 1881). OT: Masoretic Text with some Septuagint influence). |

| RSV | Revised Standard Version | 1946 (NT), 1952 (OT) | Version available from 1957 | Formal equivalence | NT: Novum Testamentum Graece. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia with limited Dead Sea Scrolls and Septuagint influence. Apocrypha: Septuagint with Vulgate influence. |

| NEB | New English Bible | 1961 (NT), 1970 (OT) | Version available from 1970 | Dynamic equivalence | NT: R.V.G. Tasker Greek New Testament. OT: Biblia Hebraica (Kittel) 3rd Edition. |

| NASB | New American Standard Bible | 1963 (NT), 1971 (OT), 1995 (update) | No | Formal equivalence |

|

| AMP | The Amplified Bible | 1958 (NT), 1965 (OT) | No | Dynamic equivalence | |

| GNB | Good News Bible | 1966 (NT), 1976 (OT) | Version available from 1979 | Dynamic equivalence, paraphrase | NT: Medium Correspondence to Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece 27th edition |

| LB | The Living Bible | 1971 | No | Paraphrase | Paraphrase of American Standard Version, 1901, with comparisons of other translations, including the King James Version, and some Greek texts. |

| NIV | New International Version | 1973 (NT), 1978 (OT) | No | Optimal equivalence |

|

| NKJV | New King James Version | 1979 (NT), 1982 (OT) | No | Formal equivalence | NT: Textus Receptus, derived from the Byzantine text-type. OT: Masoretic Text with Septuagint influence |

| NRSV | New Revised Standard Version | 1989 | Version available from 1989 | Formal equivalence | OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia with Dead Sea Scrolls and Septuagint influence. Apocrypha: Septuagint (Rahlfs) with Vulgate influence. NT: United Bible Societies' The Greek New Testament (3rd ed. corrected). 81% correspondence to Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece 27th edition.[44] |

| REB | Revised English Bible | 1989 | Version available | Dynamic equivalence | NT: Medium correspondence to Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece 27th edition, with occasional parallels to Codex Bezae. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1967/77) with Dead Sea Scrolls and Septuagint influence. Apocrypha: Septuagint with Vulgate influence. |

| GW | God's Word Translation | 1995 | No | Optimal equivalence | NT: Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament 27th edition. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. |

| CEV | Contemporary English Version | 1991 (NT), 1995 (OT) | Version available from 1999 | Dynamic equivalence | |

| NLT | New Living Translation | 1996 | Version available | Dynamic equivalence |

|

| HCSB | Holman Christian Standard Bible | 1999 (NT), 2004 (OT) | No | Optimal equivalence | NT: Novum Testamentum Graece 27th edition. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia with some Septuagint influence. |

| ESV | English Standard Version | 2001 | Version available from 2009 | Formal equivalence |

|

| MSG | The Message | 2002 | Version available from 2013 | Highly idiomatic paraphrase / Extreme dynamic equivalence | |

| CEB | Common English Bible | 2010 (NT), 2011 (OT) | Yes | Dynamic equivalence | OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (4th edition), Biblia Hebraica Quinta (5th edition) Apoc.: Göttingen Septuagint (in progress), Rahlfs' Septuagint (2005) NT: Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament (27th edition). |

| MEV | Modern English Version | 2011 (NT), 2014 (OT) | Formal equivalence | NT: Textus Receptus OT: Jacob ben Hayyim Masoretic Text | |

| CSB | Christian Standard Bible | 2017 | Optimal equivalence | NT: Novum Testamentum Graece 28th edition. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia 5th Edition with some Septuagint influence. | |

| EHV | Evangelical Heritage Version | 2017 (NT), 2019 (OT) | No | Balanced between formal and dynamic | OT: Various. Includes Masoretic Text, and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. NT: Various. Includes Textus Receptus and Novum Testamentum Graecae. |

| LSV | Literal Standard Version | 2020 | No | Formal Equivalence | Major revision of Young's Literal Translation OT: Masoretic Text with strong Septuagint influence and some reference to the Dead Sea Scrolls. NT: Textus Receptus and the Majority Text. |

A 2014 study into the Bible in American Life found that of those survey respondents who read the Bible, there was an overwhelming favouring of Protestant translations. 55% reported using the King James Version, followed by 19% for the New International Version, 7% for the New Revised Standard Version (printed in both Protestant and Catholic editions), 6% for the New American Bible (a Catholic Bible translation) and 5% for the Living Bible. Other versions were used by fewer than 10%.[52] A 2015 report by the California-based Barna Group found that 39% of American readers of the Bible preferred the King James Version, followed by 13% for the New International Version, 10% for the New King James Version and 8% for the English Standard Version. No other version was favoured by more than 3% of the survey respondents.[53]

Notes

- The Apocrypha is not included in editions of the ESV published by Crossway, the copyright holder and original publisher of the English Standard Version. ESV editions licensed by Crossway that feature a translation of the Apocrypha can be found from various publishers. For example, the English Standard Version Bible with Apocrypha,[49] published by Oxford University Press in 2009, and the ESV: Anglican Edition,[50] published by Anglican Liturgy Press in 2019.

References

- Lobenstein-Reichmann, Anja (29 March 2017). "Martin Luther, Bible Translation, and the German Language". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.382. ISBN 9780199340378.

- Meade, John (7 November 2021). "Why Are Protestant and Catholic Bibles Different?". Text & Canon Institute.

- King James Version Apocrypha, Reader's Edition. Hendrickson Publishers. 2009. p. viii. ISBN 9781598564648.

The version of 1611, following its mandate to revise and standardize the English Bible tradition, included the fourteen (or fifteen) books of the Apocrypha in a section between the Old and New Testaments (see the chart on page vi). Because of the Thirty-Nine Articles, there was no reason for King James' translators to include any comments as to the status of these books, as had the earlier English translators and editors.

- Tedford, Marie; Goudey, Pat (2008). The Official Price Guide to Collecting Books. House of Collectibles. p. 81. ISBN 9780375722936.

Up until the 1880s every Protestant Bible (not just Catholic Bibles) had 80 books, not 66. The inter-testamental books written hundreds of years before Christ, called the "Aprocrypha," were part of virtually every printing of the Tyndale-Matthews Bible, the Great Bible, the Bishops Bible, the Protestant Geneva Bible, and the King James Bible until their removal in the 1880s. The original 1611 King James contained the Apocrypha, and King James threatened anyone who dared to print the Bible without the Apocrypha with heavy fines and a year in jail.

- Roman Catholic Code of Canon Law, 825

- Henze, Matthias; Boccaccini, Gabriele (20 November 2013). Fourth Ezra and Second Baruch: Reconstruction after the Fall. Brill. p. 383. ISBN 9789004258815.

Why 3 and 4 Esdras (called 1 and 2 Esdras in the NRSV Apocrypha) are pushed to the front of the list is not clear, but the motive may have been to distinguish the Anglican Apocrypha from the Roman Catholic canon affirmed at the fourth session of the Council of trent in 1546, which included all of the books in the Anglican Apocrypha list except 3 and 4 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh. These three texts were designated at Trent as Apocrypha and later included in an appendix to the Clementine Vulgate, first published in 1592 (and the standard Vulgate text until Vatican II).

- Bruce, F.F. "The Canon of Scripture". IVP Academic, 2010, Location 1478–86 (Kindle Edition).

- Readings from the Apocrypha. Forward Movement Publications. 1981. p. 5.

- Howsham, L. Cheap Bibles: Nineteenth-Century Publishing and the British and Foreign Bible Society. Cambridge University Press, Aug 8, 2002.

- Ewert, David (11 May 2010). A General Introduction to the Bible: From Ancient Tablets to Modern Translations. Zondervan. p. 104. ISBN 9780310872436.

English Bibles were patterned after those of the Continental Reformers by having the Apocrypha set off from the rest of the OT. Coverdale (1535) called them "Apocrypha". All English Bibles prior to 1629 contained the Apocrypha. Matthew's Bible (1537), the Great Bible (1539), the Geneva Bible (1560), the Bishop's Bible (1568), and the King James Bible (1611) contained the Apocrypha. Soon after the publication of the KJV, however, the English Bibles began to drop the Apocrypha and eventually they disappeared entirely. The first English Bible to be printed in America (1782–83) lacked the Apocrypha. In 1826 the British and Foreign Bible Society decided to no longer print them. Today the trend is in the opposite direction, and English Bibles with the Apocrypha are becoming more popular again.

- Carson, D. A. (2 January 1997). "The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: An Evangelical View". In Kohlenberger, John R. (ed.). The Parallel Apocrypha (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. xliv–xlvii. ISBN 978-0195284447.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Jan Hus". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Békesi Emil (1880). "Adalékok a legrégibb magyar szentírás korának meghatározásához". Magyar Sion (in Hungarian).

- Schaff, Philip. Creeds of the Evangelical Protestant Churches, French Confession of Faith, p. 361; Belgic Confession 4. Canonical Books of the Holy Scripture; Westminster Confession of Faith, 1646; The 1577 Lutheran Epitome of the Formula of Concord

- Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. Volume 3, p. 98 James L. Schaaf, trans. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–1993. ISBN 0-8006-2813-6

- Werrell, Ralph S. (2013). The Roots of William Tyndale's Theology. James Clarke & Co. p. 42. ISBN 9780227174029.

- "1. From Wycliffe to King James (The Period of Challenge) | Bible.org".

- The Holy Bible ... With a General Introduction and Short Explanatory Notes, by B. Boothroyd. James Duncan. 1836.

- Fallows, Samuel; et al., eds. (1910) [1901]. The Popular and Critical Bible Encyclopædia and Scriptural Dictionary, Fully Defining and Explaining All Religious Terms, Including Biographical, Geographical, Historical, Archæological and Doctrinal Themes. The Howard-Severance co. p. 521.

- Paul Arblaster, Gergely Juhász, Guido Latré (eds) Tyndale's Testament, Brepols 2002, ISBN 2-503-51411-1, p. 120.

- Rosales, Raymond S. Casiodoro de Reina: Patriarca del Protestantismo Hispano. St. Louis: Concordia Seminary Publications. 2002.

- González, Jorge A. The Reina–Valera Bible: From Dream to Reality Archived 2007-09-18 at the Wayback Machine

- James Dixon Douglas, Merrill Chapin Tenney (1997), Diccionario Bíblico Mundo Hispano, Editorial Mundo Hispano, pág 145.

- "Sagradas Escrituras (1569) Bible, SEV". biblestudytools.com. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- A facsimile edition was produced by the Spanish Bible Society: (Sagrada Biblia. Traducción de Casiodoro de Reina 1569. Revisión de Cipriano de Valera 1602. Facsímil. 1990, Sociedades Biblicas Unidas, ISBN 84-85132-72-6)]

- TBS Bibles

- Kenyon, Sir Frederic G. (1909). "English Versions". In James Hastings (ed.). Hastings' Dictionary of the Bible. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-1-56563-915-7.

- Howsam, Leslie (2002). Cheap Bibles. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-521-52212-0.

- Flick, Dr. Stephen. "Canonization of the Bible". Christian heritage fellowship. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- Anderson, Charles R. (2003). Puzzles and Essays from "The Exchange": Tricky Reference Questions. Psychology Press. p. 123. ISBN 9780789017628.

Paper and printing were expensive and early publishers were able to hold down costs by eliminating the Apocrypha once it was deemed secondary material.

- McGrath, Alister (10 December 2008). In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 298. ISBN 9780307486226.

- Browne, George (1859). History of the British and Foreign Bible Society. The Society's house. p. 362.

- American Bible Society (1966). The Many Faces of the Bible. Washington Cathedral Rare Book Library. p. 23.

- "Why are Protestant and Catholic Bibles different?".

- Manser, Martin H.; Beaumont, Michael H. (5 September 2017). The Christian Basics Bible. Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. p. 1057. ISBN 9781496413574.

- DA Carson (1997) The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: An Evangelical View

- Lambert, Lance. "400 Silent Years: Anything but Silent". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Library of Congress Rule Interpretations, C.8. http://www.itsmarc.com/crs/mergedProjects/lcri/lcri/c_8__lcri.htm

- "Catholic Edition of ESV Bible Launched". Daijiworld. 10 February 2018.

- "On Translating the Old Testament: The Achievement of William Tyndale".

- "More Information about NASB 2020". The Lockman Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

For the Old Testament: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) and Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ) for the books available. Also the LXX, DSS, the Targums, and other ancient versions when pertinent.

- "More Information about NASB 2020". The Lockman Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

For the New Testament: NA28 supplemented by the new textual criticism system that uses all the available Gr mss. known as the ECM2.

- "The New International Version". Biblia. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Clontz (2008), "The Comprehensive New Testament", ranks the NRSV in eighth place in a comparison of twenty-one translations, at 81% correspondence to the Nestle-Aland 27th ed. ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- "Translation Process". Tyndale. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

The Old Testament translators used the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible as represented in Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1977), with its extensive system of textual notes ... The translators also further compared the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Septuagint and other Greek manuscripts, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Syriac Peshitta, the Latin Vulgate, and any other versions or manuscripts that shed light on the meaning of difficult passages.

- "Translation Process". Tyndale. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

The New Testament translators used the two standard editions of the Greek New Testament: the Greek New Testament, published by the United Bible Societies (UBS, fourth revised edition, 1993), and Novum Testamentum Graece, edited by Nestle and Aland (NA, twenty-seventh edition, 1993) ... However, in cases where strong textual or other scholarly evidence supported the decision, the translators sometimes chose to differ from the UBS and NA Greek texts and followed variant readings found in other ancient witnesses. Significant textual variants of this sort are always noted in the textual notes of the New Living Translation.

- "Preface to the English Standard Version". ESV.org. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

The ESV is based on the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible as found in Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (5th ed., 1997) ... The currently renewed respect among Old Testament scholars for the Masoretic text is reflected in the ESV's attempt, wherever possible, to translate difficult Hebrew passages as they stand in the Masoretic text rather than resorting to emendations or to finding an alternative reading in the ancient versions. In exceptional, difficult cases, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Syriac Peshitta, the Latin Vulgate, and other sources were consulted to shed possible light on the text, or, if necessary, to support a divergence from the Masoretic text.

- "Preface to the English Standard Version". ESV.org. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

[The ESV is based] on the Greek text in the 2014 editions of the Greek New Testament (5th corrected ed.), published by the United Bible Societies (UBS), and Novum Testamentum Graece (28th ed., 2012), edited by Nestle and Aland ... in a few difficult cases in the New Testament, the ESV has followed a Greek text different from the text given preference in the UBS/Nestle-Aland 28th edition.

- English Standard Version Bible with Apocrypha. New York: Oxford University Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-1952-8910-7. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021.

- ESV: Anglican Edition. Huntington Beach, CA: Anglican Liturgy Press. 2019. ISBN 978-1-7323448-6-0.

- "Preface to the Apocrypha". ESV: Anglican Edition. Huntington Beach, CA: Anglican Liturgy Press. 2019. pp. 1047–1048. ISBN 978-1-7323448-6-0.

- Goff, Philip. Farnsley, Arthur E. Thuesen, Peter J. The Bible in American Life, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, p. 12 Archived 2014-05-30 at the Wayback Machine

- State of the Bible 2015 americanbible.org