Proganochelys

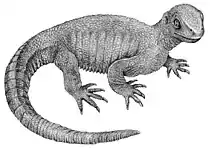

Proganochelys is an extinct, primitive stem-turtle that has been hypothesized to be the sister taxon to all other turtles creating a monophyletic group, the Casichelydia.[1] Proganochelys was named by Georg Baur in 1887 as the oldest turtle in existence at the time. The name Proganochelys comes from the Greek word ganos meaning 'brightness', combined with prefix pro, 'before', and Greek base chelys meaning 'turtle'. Proganochelys is believed to have been around 1 meter in size and herbivorous in nature. Proganochelys was known as the most primitive stem-turtle for over a century, until the novel discovery of Odontochelys in 2008.[2] Odontochelys and Proganochelys share unique primitive features that are not found in Casichelydia, such as teeth on the pterygoid and vomer and a plate-like coracoid.[2]

| Proganochelys Temporal range: Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of Proganochelys quenstedti, American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Pantestudines |

| Clade: | Testudinata |

| Genus: | †Proganochelys Baur, 1887 |

| Species: | †P. quenstedti |

| Binomial name | |

| †Proganochelys quenstedti Baur, 1887 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Proganochelys is the oldest stem-turtle species with a complete shell discovered to date, known from fossils found in Germany, Switzerland, Greenland, and Thailand in strata from the late Triassic, dating to approximately 210 million years ago.[3] The location of these fossils suggest that Proganochelys was active throughout the continent of Laurasia. There are only two known species of Proganchelys, with little information as a result of a small fossil record. All Proganochelys quentesti fossils were discovered in Germany, while Proganochelys ruchae fossils were found in Thailand.

Psammochelys, Stegochelys, and Triassochelys are junior synonyms of Proganochelys. Chelytherium von Meyer, 1863 has been considered a synonym of Proganochelys by some authors, but Joyce (2017) considers it a nomen dubium given the fragmentary nature of the syntype material. Joyce (2017) also considered North American genus Chinlechelys to be a junior synonym of Proganochelys, though the author maintains the type species of the former genus, C. tenertesta, as a distinct species within the genus Proganochelys.[4]

Description and paleobiology

Proganochelys was once considered to be the oldest known stem-turtle until the description of Odontochelys and Eorhynchochelys, a slightly earlier genera that lived in the Carnian stage of the Triassic. In had a fully developed shell 60–70 cm (2.0–2.3 ft) long.[5] A total length of Proganochelys was about 91 cm (3 ft). Its overall appearance resembled modern turtles in many respects: it lacked teeth on the upper and lower jaw, likely had a beak and had the characteristic heavily armored shell formed from bony plates and ribs which fused together into a solid cage around the internal organs. Proganochelys had a semi-beak like structure along with teeth fused to its vomer. The plates comprising the carapace and plastron were already in the modern form, although there were additional plates along the margins of the shell that would have served to protect the legs. Also unlike any modern species of turtle, its long tail had spikes and terminated in a club, its head could not be retracted under the shell and its neck may have been protected by small spines. While it had no teeth in its jaws, it did have small denticles on the palate.[6] The beak like structure suggests that the Triassic stem-turtles evolved from carnivorous stem-turtles to herbivorous as the loss of teeth and gain of the beak would benefit the crushing of plants in these stem-turtles.

Synapomorphies and autapomorphies

Proganochelys possess a few chelonian synapomorphies including: a bony shell containing fused ribs, neural bones with fused thoracic segments, and a carapace and plastron that enclose the pelvic and shoulder girdle.[1] Proganochelys was also known for its autapomorphy features which included a tail club and a tubercle on the basioccipital.[1] The tail of Proganochelys was noticeably long and is hypothesized to have been used as a club for protection against predators. Although evolution of the shell has been clearly defined, the mechanisms behind the movement of the neck has been a subject of debate for Proganochelys. It has been hypothesized that Proganochelys were able to retract their necks by tucking in their skull under the front of their shell when needed.[7]

Shell

The broadened ribs on Proganochelys show "metaplastic ossification of the dermis".[8] The enlarged ribs suggest that the endochondral rib ossifications were joined by a second ossification instead of having expanded ribs.[8] The 220-million-year-old stem-turtle Odontochelys only has a partially formed shell.[9] Odontochelys is believed to only possess the underside element of a shell known as a plastron. The 5-million-year difference that distinguish Odontochelys from Proganochelys tell us that the evolution of the shell occurred relatively quickly in time.[8] Proganochelys possess both a carapace, the upper formation of the shell, and the plastron, the lower. The shell is believed to be used for protection an enhanced feature for survival. Proganochelys fits well into the order as a turtle, as the shell of Proganochelys is in agreement with the evolution of other stem-turtles.[1]

Skull

The dermal roofing elements of Proganochelys include a large nasal, a fully roofed skull, a flat squamosal, and an absent pineal foramen.[1] Palatal characteristics include paired vomers, and a dorsal process containing premaxilla.[1] An open interpterygoid vacuity along with a prominent elongated quadrate are notable basicranial elements.[1] Overall, Pragonchelys is characterized by having few chelonian features and having a relatively generalized amniote skull.[1] The skull of Proganochelys Quenstedti from Trossingen, West Germany, retains a number of well-known amniote features not found in any other turtle. For instance, the lacrimal bone, supratemporal bone, and lacrimal duct are notable structures that are kept.[1] Furthermore, some traits that are present in modern turtles are not present in Proganochelys and therefore must have come after the evolution of the shell. For instance, jaw differentiation, the fusion of the vomer, and the loss of the lacrimal are clear examples of traits that evolved after the evolution of the shell in Proganochelys.[10]

Discovery

The earliest fossils of Proganochelys were discovered in Germany in the rural towns of Halberstadt, Tübingen, and Trossingen.[11] The fossils were found in an elaborate formation of shales, sandstones, and some limestone piles, with the formation believed to be between 220 and 205 million years old.[11] Consensus among Geologists placed the fossils in the middle of the Norian, around 210 million years ago, although this is largely an estimate.[11] In addition to Proganochelys, the rock formations in Germany have also given fossils for the stem-turtle Proterochersis.[1] Fossils have also been found the Klettgau Formation of Switzerland.[12]

Paleoecology

The specific ecology of the Late Triassic stem-turtles has been disputed and a major point of disagreement for many years among scientists.[13] Triassic stem-turtles, including Proganochelys, appear to have been both aquatic and terrestrial.[13] Shell proportions are believed to be correlated to the environment in which a turtle lives in, seen in modern turtles today. Using this concept, scientists were able to infer on the habitat in which Proganochelys may have lived in. A comparison between modern turtles and Proganochelys found that it was not likely that stem-turtles had differentiated into specialized ecologies such as open water swimmers or solely terrestrial turtles in the Late Triassic period.[13] If this is the case, a freshwater habitat would be the most likely environment for Proganochelys to have lived in. On the other hand, it is noted that some believe Proganochelys were solely terrestrial. Shell bone histology of extant turtles revealed congruence with terrestrial turtles for the earliest basal turtles, including Proganochelys, taxa in one study.[14] The common ancestry of all living turtles is believed to be aquatic, while the earliest turtles are believed to have lived in a terrestrial environment.[15]

Environment and forelimbs

Forelimbs are believed to be a physical feature that reflects the preferences and adaptations to a specific environment, indicating the environment a turtle would be most likely to reside in. Based on morphological data, Proganochelys is believed to have lived in a semi-aquatic environment,[15] though a 2021 study groups it with tortoises and other terrestrial taxa.[16] Turtles possessing short hands are believed to be most likely terrestrial, while turtles with long limbs are more likely to be aquatic.[15] The majority of all testudines are short-handed and terrestrial, while all cheloniods are long-handed and aquatic.[15]

Classification

Proganochelys belongs to the group of tetrapods with a shell known as Testudinata and is the oldest primitive stem turtle. The group does not include Odontochelys.

The cladogram below follows an analysis by Jérémy Anquetin (2012).[17]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Habitat

Proganochelys is considered to have lived in the giant continent Laurasia during the Triassic period. The fossil records show that Proganochelys might have lived anywhere in between Thailand and Germany. During the Triassic period, Laurasia was primarily dry and warm, especially in arid areas. Proganochelys shared their environment with a variety of dinosaurs. Proganochelys lived in small water bodies such as ponds, but it was mainly earthbound.

References

- Gaffney, E. S.; Meeker, L. J. (1983). "Skull morphology of the oldest turtles: a preliminary description of Proganochelys quenstedti". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 3 (1): 25–28. doi:10.1080/02724634.1983.10011953.

- Li, C.; Wu, X.-C.; Rieppel, O.; Wang, L.-T.; Zhao, L.-J. (2008). "An ancestral turtle from the Late Triassic of southwestern China" (PDF). Nature. 456 (7221): 497–501. Bibcode:2008Natur.456..497L. doi:10.1038/nature07533. PMID 19037315. S2CID 4405644.

- Prothero, D. R. (2015). The Story of Life in 25 Fossils: Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of Evolution. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231539425.

- Joyce, W. G. (2017). "A Review of the Fossil Record of Basal Mesozoic Turtles" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 58 (1): 65–113. doi:10.3374/014.058.0105. S2CID 54982901.

- Hans-Dieter Sues (August 6, 2019). The Rise of Reptiles. 320 Million Years of Evolution. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 9781421428680.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- Werneburg, I. (2015). "Neck motion in turtles and its relation to the shape of the temporal skull region". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 14 (6–7): 527–548. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2015.01.007.

- Lyson, T. R.; Bever, G. S.; Bhullar, B.-A. S.; Joyce, W. G.; Gauthier, J. A. (2010). "Transitional fossils and the origin of turtles". Biology Letters. 6 (6): 830–833. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0371. PMC 3001370. PMID 20534602.

- Schoch, R. R.; Sues, H.-D. (2015). "A Middle Triassic stem-turtle and the evolution of the turtle body plan". Nature. 523 (7562): 584–587. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..584S. doi:10.1038/nature14472. PMID 26106865. S2CID 205243837.

- Lee, M. S. Y. (1993). "The Origin of the Turtle Body Plan: Bridging a Famous Morphological Gap". Science. 261 (5129): 1716–1720. Bibcode:1993Sci...261.1716L. doi:10.1126/science.261.5129.1716. PMID 17794877. S2CID 32907587.

- Gaffney, E. (1990). The comparative osteology of the Triassic turtle Proganochelys. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 194. hdl:2246/884. ISSN 0003-0090.

- Scheyer, Torsten M.; Klein, Nicole; Evers, Serjoscha W.; Mautner, Anna-Katharina; Pabst, Ben (December 2022). "First evidence of Proganochelys quenstedtii (Testudinata) from the Plateosaurus bonebeds (Norian, Late Triassic) of Frick, Canton Aargau, Switzerland". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 141 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/s13358-022-00260-4. ISSN 1664-2376. PMC 9613585. PMID 36317153.

- Lichtig, A. J.; Lucas, S. G. (2017). "A simple method for inferring habitats of extinct turtles". Palaeoworld. 26 (3): 581–588. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2017.02.001.

- Scheyer, T. M.; Sander, P. M. (2007). "Shell bone histology indicates terrestrial palaeoecology of basal turtles". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1620): 1885–1893. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0499. PMC 2270937. PMID 17519193.

- Joyce, W. G.; Gauthier, J. A. (2004). "Palaeoecology of Triassic stem turtles sheds new light on turtle origins". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1534): 1–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2523. PMC 1691562. PMID 15002764.

- Dudgeon, Thomas W.; Livius, Marissa C. H.; Alfonso, Noel; Tessier, Stéphanie; Mallon, Jordan C. (2021). "A new model of forelimb ecomorphology for predicting the ancient habitats of fossil turtles". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (23): 17071–17079. doi:10.1002/ece3.8345. PMC 8668755. PMID 34938493. S2CID 244700219.

- Anquetin, J. (2012). "Reassessment of the phylogenetic interrelationships of basal turtles (Testudinata)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (1): 3–45. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.558928. S2CID 85295987.