Flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift associated with gliding or propulsive thrust, aerostatically using buoyancy, or by ballistic movement.

_arrives_London_Heathrow_11Apr2015_arp.jpg.webp)

Many things can fly, from animal aviators such as birds, bats and insects, to natural gliders/parachuters such as patagial animals, anemochorous seeds and ballistospores, to human inventions like aircraft (airplanes, helicopters, airships, balloons, etc.) and rockets which may propel spacecraft and spaceplanes.

The engineering aspects of flight are the purview of aerospace engineering which is subdivided into aeronautics, the study of vehicles that travel through the atmosphere, and astronautics, the study of vehicles that travel through space, and ballistics, the study of the flight of projectiles.

Types of flight

Buoyant flight

Humans have managed to construct lighter-than-air vehicles that raise off the ground and fly, due to their buoyancy in the air.

An aerostat is a system that remains aloft primarily through the use of buoyancy to give an aircraft the same overall density as air. Aerostats include free balloons, airships, and moored balloons. An aerostat's main structural component is its envelope, a lightweight skin that encloses a volume of lifting gas[1][2] to provide buoyancy, to which other components are attached.

Aerostats are so named because they use "aerostatic" lift, a buoyant force that does not require lateral movement through the surrounding air mass to effect a lifting force. By contrast, aerodynes primarily use aerodynamic lift, which requires the lateral movement of at least some part of the aircraft through the surrounding air mass.

Unpowered flight versus powered flight

Some things that fly do not generate propulsive thrust through the air, for example, the flying squirrel. This is termed gliding. Some other things can exploit rising air to climb such as raptors (when gliding) and man-made sailplane gliders. This is termed soaring. However most other birds and all powered aircraft need a source of propulsion to climb. This is termed powered flight.

Animal flight

The only groups of living things that use powered flight are birds, insects, and bats, while many groups have evolved gliding. The extinct pterosaurs, an order of reptiles contemporaneous with the dinosaurs, were also very successful flying animals,[3] and there were apparently some flying dinosaurs (see Flying and gliding animals#Non-avian dinosaurs). Each of these groups' wings evolved independently, with insects the first animal group to evolve flight.[4] The wings of the flying vertebrate groups are all based on the forelimbs, but differ significantly in structure; those of insects are hypothesized to be highly modified versions of structures that form gills in most other groups of arthropods.[3]

Bats are the only mammals capable of sustaining level flight (see bat flight).[5] However, there are several gliding mammals which are able to glide from tree to tree using fleshy membranes between their limbs; some can travel hundreds of meters in this way with very little loss in height. Flying frogs use greatly enlarged webbed feet for a similar purpose, and there are flying lizards which fold out their mobile ribs into a pair of flat gliding surfaces. "Flying" snakes also use mobile ribs to flatten their body into an aerodynamic shape, with a back and forth motion much the same as they use on the ground.

Flying fish can glide using enlarged wing-like fins, and have been observed soaring for hundreds of meters. It is thought that this ability was chosen by natural selection because it was an effective means of escape from underwater predators. The longest recorded flight of a flying fish was 45 seconds.[6]

Most birds fly (see bird flight), with some exceptions. The largest birds, the ostrich and the emu, are earthbound flightless birds, as were the now-extinct dodos and the Phorusrhacids, which were the dominant predators of South America in the Cenozoic era. The non-flying penguins have wings adapted for use under water and use the same wing movements for swimming that most other birds use for flight. Most small flightless birds are native to small islands, and lead a lifestyle where flight would offer little advantage.

Among living animals that fly, the wandering albatross has the greatest wingspan, up to 3.5 meters (11 feet); the great bustard has the greatest weight, topping at 21 kilograms (46 pounds).[7]

Most species of insects can fly as adults. Insect flight makes use of either of two basic aerodynamic models: creating a leading edge vortex, found in most insects, and using clap and fling, found in very small insects such as thrips.[8][9]

Many species of spiders, spider mites and lepidoptera use a technique called ballooning to ride air currents such as thermals, by exposing their gossamer threads which gets lifted by wind and atmospheric electric fields.

Mechanical

Mechanical flight is the use of a machine to fly. These machines include aircraft such as airplanes, gliders, helicopters, autogyros, airships, balloons, ornithopters as well as spacecraft. Gliders are capable of unpowered flight. Another form of mechanical flight is para-sailing, where a parachute-like object is pulled by a boat. In an airplane, lift is created by the wings; the shape of the wings of the airplane are designed specially for the type of flight desired. There are different types of wings: tempered, semi-tempered, sweptback, rectangular and elliptical. An aircraft wing is sometimes called an airfoil, which is a device that creates lift when air flows across it.

Supersonic

Supersonic flight is flight faster than the speed of sound. Supersonic flight is associated with the formation of shock waves that form a sonic boom that can be heard from the ground,[10] and is frequently startling. This shockwave takes quite a lot of energy to create and this makes supersonic flight generally less efficient than subsonic flight at about 85% of the speed of sound.

Hypersonic

Hypersonic flight is very high speed flight where the heat generated by the compression of the air due to the motion through the air causes chemical changes to the air. Hypersonic flight is achieved primarily by reentering spacecraft such as the Space Shuttle and Soyuz.

Ballistic

Atmospheric

Some things generate little or no lift and move only or mostly under the action of momentum, gravity, air drag and in some cases thrust. This is termed ballistic flight. Examples include balls, arrows, bullets, fireworks etc.

Spaceflight

Essentially an extreme form of ballistic flight, spaceflight is the use of space technology to achieve the flight of spacecraft into and through outer space. Examples include ballistic missiles, orbital spaceflight, etc.

Spaceflight is used in space exploration, and also in commercial activities like space tourism and satellite telecommunications. Additional non-commercial uses of spaceflight include space observatories, reconnaissance satellites and other Earth observation satellites.

A spaceflight typically begins with a rocket launch, which provides the initial thrust to overcome the force of gravity and propels the spacecraft from the surface of the Earth.[11] Once in space, the motion of a spacecraft—both when unpropelled and when under propulsion—is covered by the area of study called astrodynamics. Some spacecraft remain in space indefinitely, some disintegrate during atmospheric reentry, and others reach a planetary or lunar surface for landing or impact.

Solid-state propulsion

In 2018, researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) managed to fly an aeroplane with no moving parts, powered by an "ionic wind" also known as electroaerodynamic thrust.[12][13]

History

Many human cultures have built devices that fly, from the earliest projectiles such as stones and spears,[14][15] the boomerang in Australia, the hot air Kongming lantern, and kites.

Aviation

George Cayley studied flight scientifically in the first half of the 19th century,[16][17][18] and in the second half of the 19th century Otto Lilienthal made over 200 gliding flights and was also one of the first to understand flight scientifically. His work was replicated and extended by the Wright brothers who made gliding flights and finally the first controlled and extended, manned powered flights.[19]

Spaceflight

Spaceflight, particularly human spaceflight became a reality in the 20th century following theoretical and practical breakthroughs by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Robert H. Goddard. The first orbital spaceflight was in 1957,[20] and Yuri Gagarin was carried aboard the first crewed orbital spaceflight in 1961.[21]

Physics

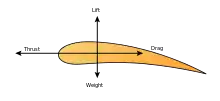

There are different approaches to flight. If an object has a lower density than air, then it is buoyant and is able to float in the air without expending energy. A heavier than air craft, known as an aerodyne, includes flighted animals and insects, fixed-wing aircraft and rotorcraft. Because the craft is heavier than air, it must generate lift to overcome its weight. The wind resistance caused by the craft moving through the air is called drag and is overcome by propulsive thrust except in the case of gliding.

Some vehicles also use thrust for flight, for example rockets and Harrier jump jets.

Finally, momentum dominates the flight of ballistic flying objects.

Forces

Forces relevant to flight are[22]

- Propulsive thrust (except in gliders)

- Lift, created by the reaction to an airflow

- Drag, created by aerodynamic friction

- Weight, created by gravity

- Buoyancy, for lighter than air flight

These forces must be balanced for stable flight to occur.

Thrust

A fixed-wing aircraft generates forward thrust when air is pushed in the direction opposite to flight. This can be done in several ways including by the spinning blades of a propeller, or a rotating fan pushing air out from the back of a jet engine, or by ejecting hot gases from a rocket engine.[23] The forward thrust is proportional to the mass of the airstream multiplied by the difference in velocity of the airstream. Reverse thrust can be generated to aid braking after landing by reversing the pitch of variable-pitch propeller blades, or using a thrust reverser on a jet engine. Rotary wing aircraft and thrust vectoring V/STOL aircraft use engine thrust to support the weight of the aircraft, and vector sum of this thrust fore and aft to control forward speed.

Lift

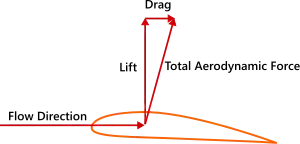

In the context of an air flow relative to a flying body, the lift force is the component of the aerodynamic force that is perpendicular to the flow direction.[24] Aerodynamic lift results when the wing causes the surrounding air to be deflected - the air then causes a force on the wing in the opposite direction, in accordance with Newton's third law of motion.

Lift is commonly associated with the wing of an aircraft, although lift is also generated by rotors on rotorcraft (which are effectively rotating wings, performing the same function without requiring that the aircraft move forward through the air). While common meanings of the word "lift" suggest that lift opposes gravity, aerodynamic lift can be in any direction. When an aircraft is cruising for example, lift does oppose gravity, but lift occurs at an angle when climbing, descending or banking. On high-speed cars, the lift force is directed downwards (called "down-force") to keep the car stable on the road.

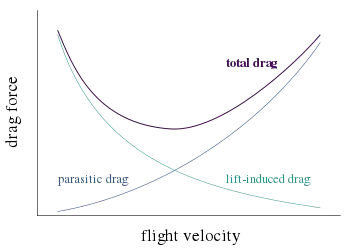

Drag

For a solid object moving through a fluid, the drag is the component of the net aerodynamic or hydrodynamic force acting opposite to the direction of the movement.[25][26][27][28] Therefore, drag opposes the motion of the object, and in a powered vehicle it must be overcome by thrust. The process which creates lift also causes some drag.

Lift-to-drag ratio

Aerodynamic lift is created by the motion of an aerodynamic object (wing) through the air, which due to its shape and angle deflects the air. For sustained straight and level flight, lift must be equal and opposite to weight. In general, long narrow wings are able deflect a large amount of air at a slow speed, whereas smaller wings need a higher forward speed to deflect an equivalent amount of air and thus generate an equivalent amount of lift. Large cargo aircraft tend to use longer wings with higher angles of attack, whereas supersonic aircraft tend to have short wings and rely heavily on high forward speed to generate lift.

However, this lift (deflection) process inevitably causes a retarding force called drag. Because lift and drag are both aerodynamic forces, the ratio of lift to drag is an indication of the aerodynamic efficiency of the airplane. The lift to drag ratio is the L/D ratio, pronounced "L over D ratio." An airplane has a high L/D ratio if it produces a large amount of lift or a small amount of drag. The lift/drag ratio is determined by dividing the lift coefficient by the drag coefficient, CL/CD.[29]

The lift coefficient Cl is equal to the lift L divided by the (density r times half the velocity V squared times the wing area A). [Cl = L / (A * .5 * r * V^2)] The lift coefficient is also affected by the compressibility of the air, which is much greater at higher speeds, so velocity V is not a linear function. Compressibility is also affected by the shape of the aircraft surfaces. [30]

The drag coefficient Cd is equal to the drag D divided by the (density r times half the velocity V squared times the reference area A). [Cd = D / (A * .5 * r * V^2)] [31]

Lift-to-drag ratios for practical aircraft vary from about 4:1 for vehicles and birds with relatively short wings, up to 60:1 or more for vehicles with very long wings, such as gliders. A greater angle of attack relative to the forward movement also increases the extent of deflection, and thus generates extra lift. However a greater angle of attack also generates extra drag.

Lift/drag ratio also determines the glide ratio and gliding range. Since the glide ratio is based only on the relationship of the aerodynamics forces acting on the aircraft, aircraft weight will not affect it. The only effect weight has is to vary the time that the aircraft will glide for – a heavier aircraft gliding at a higher airspeed will arrive at the same touchdown point in a shorter time.[32]

Buoyancy

Air pressure acting up against an object in air is greater than the pressure above pushing down. The buoyancy, in both cases, is equal to the weight of fluid displaced - Archimedes' principle holds for air just as it does for water.

A cubic meter of air at ordinary atmospheric pressure and room temperature has a mass of about 1.2 kilograms, so its weight is about 12 newtons. Therefore, any 1-cubic-meter object in air is buoyed up with a force of 12 newtons. If the mass of the 1-cubic-meter object is greater than 1.2 kilograms (so that its weight is greater than 12 newtons), it falls to the ground when released. If an object of this size has a mass less than 1.2 kilograms, it rises in the air. Any object that has a mass that is less than the mass of an equal volume of air will rise in air - in other words, any object less dense than air will rise.

Thrust to weight ratio

Thrust-to-weight ratio is, as its name suggests, the ratio of instantaneous thrust to weight (where weight means weight at the Earth's standard acceleration ).[33] It is a dimensionless parameter characteristic of rockets and other jet engines and of vehicles propelled by such engines (typically space launch vehicles and jet aircraft).

If the thrust-to-weight ratio is greater than the local gravity strength (expressed in gs), then flight can occur without any forward motion or any aerodynamic lift being required.

If the thrust-to-weight ratio times the lift-to-drag ratio is greater than local gravity then takeoff using aerodynamic lift is possible.

Flight dynamics

Flight dynamics is the science of air and space vehicle orientation and control in three dimensions. The three critical flight dynamics parameters are the angles of rotation in three dimensions about the vehicle's center of mass, known as pitch, roll and yaw (See Tait-Bryan rotations for an explanation).

The control of these dimensions can involve a horizontal stabilizer (i.e. "a tail"), ailerons and other movable aerodynamic devices which control angular stability i.e. flight attitude (which in turn affects altitude, heading). Wings are often angled slightly upwards- they have "positive dihedral angle" which gives inherent roll stabilization.

Energy efficiency

To create thrust so as to be able to gain height, and to push through the air to overcome the drag associated with lift all takes energy. Different objects and creatures capable of flight vary in the efficiency of their muscles, motors and how well this translates into forward thrust.

Propulsive efficiency determines how much energy vehicles generate from a unit of fuel.[34][35]

Range

The range that powered flight articles can achieve is ultimately limited by their drag, as well as how much energy they can store on board and how efficiently they can turn that energy into propulsion.[36]

For powered aircraft the useful energy is determined by their fuel fraction- what percentage of the takeoff weight is fuel, as well as the specific energy of the fuel used.

Power-to-weight ratio

All animals and devices capable of sustained flight need relatively high power-to-weight ratios to be able to generate enough lift and/or thrust to achieve take off.

Takeoff and landing

Vehicles that can fly can have different ways to takeoff and land. Conventional aircraft accelerate along the ground until sufficient lift is generated for takeoff, and reverse the process for landing. Some aircraft can take off at low speed; this is called a short takeoff. Some aircraft such as helicopters and Harrier jump jets can take off and land vertically. Rockets also usually take off and land vertically, but some designs can land horizontally.

Guidance, navigation and control

Navigation

Navigation is the systems necessary to calculate current position (e.g. compass, GPS, LORAN, star tracker, inertial measurement unit, and altimeter).

In aircraft, successful air navigation involves piloting an aircraft from place to place without getting lost, breaking the laws applying to aircraft, or endangering the safety of those on board or on the ground.

The techniques used for navigation in the air will depend on whether the aircraft is flying under the visual flight rules (VFR) or the instrument flight rules (IFR). In the latter case, the pilot will navigate exclusively using instruments and radio navigation aids such as beacons, or as directed under radar control by air traffic control. In the VFR case, a pilot will largely navigate using dead reckoning combined with visual observations (known as pilotage), with reference to appropriate maps. This may be supplemented using radio navigation aids.

Guidance

A guidance system is a device or group of devices used in the navigation of a ship, aircraft, missile, rocket, satellite, or other moving object. Typically, guidance is responsible for the calculation of the vector (i.e., direction, velocity) toward an objective.

Control

A conventional fixed-wing aircraft flight control system consists of flight control surfaces, the respective cockpit controls, connecting linkages, and the necessary operating mechanisms to control an aircraft's direction in flight. Aircraft engine controls are also considered as flight controls as they change speed.

Traffic

In the case of aircraft, air traffic is controlled by air traffic control systems.

Collision avoidance is the process of controlling spacecraft to try to prevent collisions.

Flight safety

Air safety is a term encompassing the theory, investigation and categorization of flight failures, and the prevention of such failures through regulation, education and training. It can also be applied in the context of campaigns that inform the public as to the safety of air travel.

See also

References

- Notes

- Walker 2000, p. 541. Quote: the gas-bag of a balloon or airship.

- Coulson-Thomas 1976, p. 281. Quote: fabric enclosing gas-bags of airship.

- Averof, Michalis. "Evolutionary origin of insect wings from ancestral gills." Nature, Volume 385, Issue 385, February 1997, pp. 627–630.

- Eggleton, Paul (2020). "The State of the World's Insects". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45: 61–82. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-050035.

- World Book Student. Chicago: World Book. Retrieved: April 29, 2011.

- "BBC article and video of flying fish." BBC, May 20, 2008. Retrieved: May 20, 2008.

- "Swan Identification." Archived 2006-10-31 at the Wayback Machine The Trumpeter Swan Society. Retrieved: January 3, 2012.

- Wang, Z. Jane (2005). "Dissecting Insect Flight" (PDF). Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 37 (1): 183–210. Bibcode:2005AnRFM..37..183W. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.121940.

- Sane, Sanjay P. (2003). "The aerodynamics of insect flight" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 206 (23): 4191–4208. doi:10.1242/jeb.00663. PMID 14581590. S2CID 17453426.

- Bern, Peter. "Concorde: You asked a pilot." BBC, October 23, 2003.

- Spitzmiller, Ted (2007). Astronautics: A Historical Perspective of Mankind's Efforts to Conquer the Cosmos. Apogee Books. p. 467. ISBN 9781894959667.

- Haofeng Xu; et al. (2018). "Flight of an aeroplane with solid-state propulsion". Vol. 563. Nature. pp. 532–535. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0707-9.

- Jennifer Chu (21 November 2018). "MIT engineers fly first-ever plane with no moving parts". MIT News.

- "Archytas of Tar entum." Archived December 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Technology Museum of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece/ Retrieved: May 6, 2012.

- "Ancient history." Archived 2002-12-05 at the Wayback Machine Automata. Retrieved:May 6, 2012.

- "Sir George Cayley". Flyingmachines.org. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

Sir George Cayley is one of the most important people in the history of aeronautics. Many consider him the first true scientific aerial investigator and the first person to understand the underlying principles and forces of flight.

- "The Pioneers: Aviation and Airmodelling". Retrieved 26 July 2009.

Sir George Cayley, is sometimes called the 'Father of Aviation'. A pioneer in his field, he is credited with the first major breakthrough in heavier-than-air flight. He was the first to identify the four aerodynamic forces of flight – weight, lift, drag, and thrust – and their relationship and also the first to build a successful human-carrying glider.

- "U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission – Sir George Cayley". Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

Sir George Cayley, born in 1773, is sometimes called the Father of Aviation. A pioneer in his field, Cayley literally has two great spurts of aeronautical creativity, separated by years during which he did little with the subject. He was the first to identify the four aerodynamic forces of flight – weight, lift, drag, and thrust and their relationship. He was also the first to build a successful human-carrying glider. Cayley described many of the concepts and elements of the modern aeroplane and was the first to understand and explain in engineering terms the concepts of lift and thrust.

- "Orville Wright's Personal Letters on Aviation." Archived 2012-06-11 at the Wayback Machine Shapell Manuscript Foundation, (Chicago), 2012.

- "Sputnik and the Origins of the Space Age".

- "Gagarin anniversary." NASA. Retrieved: May 6, 2012.

- "Four forces on an aeroplane." NASA. Retrieved: January 3, 2012.

- "Newtons Third Law". Archived from the original on 1999-11-28.

- "Definition of lift." Archived 2009-02-03 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Retrieved: May 6, 2012.

- French 1970, p. 210.

- "Basic flight physics." Berkeley University. Retrieved: May 6, 2012.

- "What is Drag?" Archived 2010-05-24 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Retrieved: May 6, 2012.

- "Motions of particles through fluids." Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine lorien.ncl.ac. Retrieved: May 6, 2012.

- The Beginner's Guide to Aeronautics - NASA Glenn Research Center https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/ldrat.html

- The Beginner's Guide to Aeronautics - NASA Glenn Research Center https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/liftco.html

- The Beginner's Guide to Aeronautics - NASA Glenn Research Center https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/dragco.html

- The Beginner's Guide to Aeronautics - NASA Glenn Research Center https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/ldrat.html

- Sutton and Biblarz 2000, p. 442. Quote: "thrust-to-weight ratio F/W0 is a dimensionless parameter that is identical to the acceleration of the rocket propulsion system (expressed in multiples of g0) if it could fly by itself in a gravity free vacuum."

- ch10-3 "History." NASA. Retrieved: May 6, 2012.

- Honicke et al. 1968

- "13.3 Aircraft Range: The Breguet Range Equation".

- Bibliography

- Coulson-Thomas, Colin. The Oxford Illustrated Dictionary. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1976, First edition 1975, ISBN 978-0-19-861118-9.

- French, A. P. Newtonian Mechanics (The M.I.T. Introductory Physics Series) (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 1970.

- Honicke, K., R. Lindner, P. Anders, M. Krahl, H. Hadrich and K. Rohricht. Beschreibung der Konstruktion der Triebwerksanlagen. Berlin: Interflug, 1968.

- Sutton, George P. Oscar Biblarz. Rocket Propulsion Elements. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 2000 (7th edition). ISBN 978-0-471-32642-7.

- Walker, Peter. Chambers Dictionary of Science and Technology. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd., 2000, First edition 1998. ISBN 978-0-550-14110-1.

External links

![]() Flight travel guide from Wikivoyage

Flight travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Pettigrew, James Bell (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). pp. 502–519. History and photographs of early aeroplanes etc.

- 'Birds in Flight and Aeroplanes' by Evolutionary Biologist and trained Engineer John Maynard-Smith Freeview video provided by the Vega Science Trust.