James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. (/bjuːˈkænən/ bew-KAN-ən;[3] April 23, 1791 – June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat, and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvania in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He was an advocate for states' rights, particularly regarding slavery, and minimized the role of the federal government preceding the Civil War.

James Buchanan | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Mathew Brady, c. 1850–1868 | |

| 15th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 4, 1861 | |

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge |

| Preceded by | Franklin Pierce |

| Succeeded by | Abraham Lincoln |

| 20th United States Minister to the United Kingdom | |

| In office August 23, 1853 – March 15, 1856 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Joseph Reed Ingersoll |

| Succeeded by | George M. Dallas |

| 17th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 10, 1845 – March 7, 1849 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | John C. Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | John M. Clayton |

| United States Senator from Pennsylvania | |

| In office December 6, 1834 – March 5, 1845 | |

| Preceded by | William Wilkins |

| Succeeded by | Simon Cameron |

| 5th United States Minister to Russia | |

| In office June 11, 1832 – August 5, 1833 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John Randolph |

| Succeeded by | William Wilkins |

| Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee | |

| In office March 5, 1829 – March 3, 1831 | |

| Preceded by | Philip P. Barbour |

| Succeeded by | Warren R. Davis |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania | |

| In office March 4, 1821 – March 3, 1831 | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Constituency |

|

| Member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives from Lancaster County | |

| In office 1814–1816 | |

| Preceded by | Emanuel Reigart, Joel Lightner, Jacob Grosh, John Graff, Henry Hambright, Robert Maxwell |

| Succeeded by | Joel Lightner, Hugh Martin, John Forrey, Henry Hambright, Jasper Slaymaker, Jacob Grosh[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 23, 1791 Cove Gap, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | June 1, 1868 (aged 77) Lancaster, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodward Hill Cemetery |

| Political party |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Education | Dickinson College (BA) |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Pennsylvania Militia |

| Years of service | 1814[2] |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | Henry Shippen's Company, 1st Brigade, 4th Division |

| Battles/wars | |

| Official name | James Buchanan |

| Type | Roadside |

| Designated | January 1955 |

Buchanan was a prominent lawyer in Pennsylvania and won his first election to the state's House of Representatives as a Federalist. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1820 and retained that post for five terms, aligning with Andrew Jackson's Democratic Party. Buchanan served as Jackson's minister to Russia in 1832. He won the election in 1834 as a U.S. senator from Pennsylvania and continued in that position for 11 years. He was appointed to serve as President James K. Polk's secretary of state in 1845, and eight years later was named as President Franklin Pierce's minister to the United Kingdom.

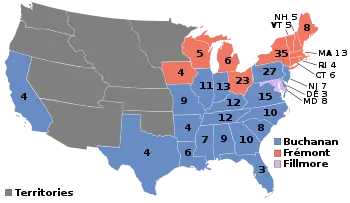

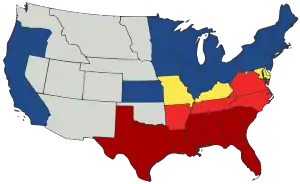

Beginning in 1844, Buchanan became a regular contender for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination. He was finally nominated in 1856, defeating incumbent Franklin Pierce and Senator Stephen A. Douglas at the Democratic National Convention. He benefited from the fact that he had been out of the country as ambassador in London and had not been involved in slavery issues. Buchanan and running mate John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky carried every slave state except Maryland, defeating anti-slavery Republican John C. Frémont and Know-Nothing former president Millard Fillmore to win the 1856 presidential election.

As President, Buchanan intervened to assure the Supreme Court's majority ruling in the pro-slavery decision in the Dred Scott case. He acceded to Southern attempts to engineer Kansas' entry into the Union as a slave state under the Lecompton Constitution, and angered not only Republicans but also Northern Democrats. Buchanan honored his pledge to serve only one term and supported Breckinridge's unsuccessful candidacy in the 1860 presidential election. He failed to reconcile the fractured Democratic Party amid the grudge against Stephen Douglas, leading to the election of Republican and former Congressman Abraham Lincoln.

Buchanan's leadership during his lame duck period, before the American Civil War, has been widely criticized. He simultaneously angered the North by not stopping secession and the South by not yielding to their demands. He supported the ineffective Corwin Amendment in an effort to reconcile the country. He made an unsuccessful attempt to reinforce Fort Sumter, but otherwise refrained from preparing the military. His failure to forestall the Civil War has been described as incompetence, and he spent his last years defending his reputation. In his personal life, Buchanan never married and was the only U.S. president to remain a lifelong bachelor, leading some historians and authors to question his sexual orientation. Buchanan died of respiratory failure in 1868 and was buried in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he had lived for nearly 60 years. Historians and scholars rank Buchanan as among the worst, if not the worst, of U.S. presidents in American history.

Early life

James Buchanan Jr. was born April 23, 1791, in a log cabin in Cove Gap, Pennsylvania, to James Buchanan Sr. (1761–1821) and Elizabeth Speer (1767–1833).[4] His parents were both of Ulster Scot descent, and his father emigrated from Ramelton, Ireland in 1783. Shortly after Buchanan's birth, the family moved to a farm near Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, and in 1794 the family moved into the town. His father became the wealthiest resident there, working as a merchant, farmer, and real estate investor.[4]

Buchanan attended the Old Stone Academy in Mercersburg and then Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.[5] He was nearly expelled for bad behavior but pleaded for a second chance and ultimately graduated with honors in 1809.[6] Later that year, he moved to the state capital at Lancaster. James Hopkins, a leading lawyer there, accepted Buchanan as an apprentice, and in 1812 he was admitted to the Pennsylvania bar. Many other lawyers moved to Harrisburg when it became the state capital in 1812, but Buchanan made Lancaster his lifelong home. His income rapidly rose after he established his practice, and by 1821 he was earning over $11,000 per year (equivalent to $240,000 in 2022). He handled various types of cases, including a much-publicized impeachment trial where he successfully defended Pennsylvania Judge Walter Franklin.[7]

Buchanan began his political career as a member of the Federalist Party, and was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1814 and 1815.[8] The legislature met for only three months a year, but Buchanan's service helped him acquire more clients.[9] Politically, he supported federally-funded internal improvements, a high tariff, and a national bank. He became a strong critic of Democratic-Republican President James Madison during the War of 1812.[10]

He was a Freemason, and served as the Master of Masonic Lodge No. 43 in Lancaster and as a District Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania.[11]

Military service

When the British invaded neighboring Maryland in 1814, he served in the defense of Baltimore as a private in Henry Shippen's Company, 1st Brigade, 4th Division, Pennsylvania Militia, a unit of yagers.[12] Buchanan is the only president with military experience who was not an officer.[13] He is also the last president who served in the War of 1812.[14]

Congressional career

U.S. House service

In 1820 Buchanan was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, though the Federalist Party was waning. As a young Representative, Buchanan was one of the most prominent leaders of the "Amalgamator party" faction of Pennsylvanian politics, named that because it was made up of both Democratic-Republicans and former Federalists. During the 1824 presidential election, Buchanan initially supported Henry Clay, but switched to Andrew Jackson (with Clay as a second choice) when it became clear that the Pennsylvanian public overwhelmingly preferred Jackson.[15] After the election, Buchanan continued supporting Jackson and helped organize his followers into the Democratic Party, afterwards becoming a prominent Pennsylvania Democrat. In Washington, Buchanan became an avid defender of states' rights, and was close with many southern Congressmen, viewing some New England Congressmen as dangerous radicals. He was appointed to the Agriculture Committee in his first year, and he eventually became Chairman of the Judiciary Committee. He declined re-nomination to a sixth term and briefly returned to private life.[16]

Minister to Russia

After Jackson was re-elected in 1832, he offered Buchanan the position of United States Ambassador to Russia. Buchanan was reluctant to leave the country but ultimately agreed. He had denounced Tsar Nicholas I as a despot merely a year prior during his tenure in Congress; many Americans had reacted negatively to Russia's reaction to the 1830 Polish uprising.[17]

He served as an ambassador for 18 months, during which time he learned French, the trade language of diplomacy in the nineteenth century. He helped negotiate commercial and maritime treaties with the Russian Empire.[18]

U.S. Senate service

Buchanan returned home and was elected by the Pennsylvania state legislature to succeed William Wilkins in the U.S. Senate. Wilkins, in turn, replaced Buchanan as the ambassador to Russia. The Jacksonian Buchanan, who was re-elected in 1836 and 1842, opposed the re-chartering of the Second Bank of the United States and sought to expunge a congressional censure of Jackson stemming from the Bank War.[19]

During the contentious 1838 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, Buchanan chose to support the Democratic challenger, David Rittenhouse Porter,[20] who was elected by fewer than 5,500 votes as Pennsylvania's first governor under the state's revised Constitution of 1838.[21][22]

Buchanan also opposed a gag rule sponsored by John C. Calhoun that would have suppressed anti-slavery petitions. He joined the majority in blocking the rule, with most senators of the belief that it would have the reverse effect of strengthening the abolitionists.[23] He said, "We have just as little right to interfere with slavery in the South, as we have to touch the right of petition."[24] Buchanan thought that the issue of slavery was the domain of the states, and he faulted abolitionists for exciting passions over the issue.[25]

His support of states' rights was matched by his support for Manifest Destiny, and he opposed the Webster–Ashburton Treaty for its "surrender" of lands to the United Kingdom. Buchanan also argued for the annexation of both Texas and the Oregon Country. In the lead-up to the 1844 Democratic National Convention, Buchanan positioned himself as a potential alternative to former President Martin Van Buren, but the nomination went to James K. Polk, who won the election.[25]

Diplomatic career

Secretary of State

Buchanan was offered the position of Secretary of State in the Polk administration, as well as the alternative of serving on the Supreme Court. He accepted the State Department post and served for the duration of Polk's single term in office. He and Polk nearly doubled the territory of the United States through the Oregon Treaty and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which included territory that is now Texas, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado.[26] In negotiations with Britain over Oregon, Buchanan at first preferred a compromise but later advocated for annexation of the entire territory. Eventually, he agreed to a division at the 49th parallel. After the outbreak of the Mexican–American War, he advised Polk against taking territory south of the Rio Grande River and New Mexico. However, as the war came to an end, Buchanan argued for the annexation of further territory, and Polk began to suspect that he was angling to become president. Buchanan did quietly seek the nomination at the 1848 Democratic National Convention, as Polk had promised to serve only one term, but Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan was nominated.[27]

Ambassador to the United Kingdom

With the 1848 election of Whig Zachary Taylor, Buchanan returned to private life. He bought the house of Wheatland on the outskirts of Lancaster and entertained various visitors while monitoring political events.[28] In 1852, he was named president of the Board of Trustees of Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, and he served in this capacity until 1866.[29] He quietly campaigned for the 1852 Democratic presidential nomination, writing a public letter that deplored the Wilmot Proviso, which proposed to ban slavery in new territories. He became known as a "doughface" due to his sympathy toward the South. At the 1852 Democratic National Convention, he won the support of many southern delegates but failed to win the two-thirds support needed for the presidential nomination, which went to Franklin Pierce. Buchanan declined to serve as the vice presidential nominee, and the convention instead nominated his close friend, William R. King. Pierce won the 1852 election, and Buchanan accepted the position of United States Minister to the United Kingdom.[30]

Buchanan sailed for England in the summer of 1853, and he remained abroad for the next three years. In 1850, the United States and Great Britain signed the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, which committed both countries to joint control of any future canal that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Central America. Buchanan met repeatedly with Lord Clarendon, the British foreign minister, in hopes of pressuring the British to withdraw from Central America. He also focused on the potential annexation of Cuba, which had long interested him.[31] At Pierce's prompting, Buchanan met in Ostend, Belgium, with U.S. Ambassador to Spain Pierre Soulé and U.S. Ambassador to France John Mason. A memorandum draft resulted, called the Ostend Manifesto, which proposed the purchase of Cuba from Spain, then in the midst of revolution and near bankruptcy. The document declared the island "as necessary to the North American republic as any of its present ... family of states". Against Buchanan's recommendation, the final draft of the manifesto suggested that "wresting it from Spain", if Spain refused to sell, would be justified "by every law, human and Divine".[32] The manifesto, generally considered a blunder, was never acted upon. It weakened the Pierce administration and reduced support for Manifest Destiny.[32][33]

Presidential election of 1856

Buchanan's service abroad allowed him to conveniently avoid the debate over the Kansas–Nebraska Act then roiling the country in the slavery dispute.[34] While he did not overtly seek the presidency, he assented to the movement on his behalf.[35] The 1856 Democratic National Convention met in June 1856, producing a platform that reflected his views, including support for the Fugitive Slave Law, which required the return of escaped slaves. The platform also called for an end to anti-slavery agitation and U.S. "ascendancy in the Gulf of Mexico".[36] President Pierce hoped for re-nomination, while Senator Stephen A. Douglas also loomed as a strong candidate.

Buchanan led on the first ballot, supported by powerful Senators John Slidell, Jesse Bright, and Thomas F. Bayard, who presented Buchanan as an experienced leader appealing to the North and South. He won the nomination after seventeen ballots. He was joined on the ticket by John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, placating supporters of Pierce and Douglas, also allies of Breckinridge.[37]

Buchanan faced two candidates in the general election: former Whig President Millard Fillmore ran as the American Party (or "Know-Nothing") candidate, while John C. Frémont ran as the Republican nominee. Buchanan did not actively campaign, but he wrote letters and pledged to uphold the Democratic platform. In the election, he carried every slave state except for Maryland, as well as five slavery-free states, including his home state of Pennsylvania.[37] He won 45 percent of the popular vote and decisively won the electoral vote, taking 174 of 296 votes. His election made him the first president from Pennsylvania.

In a combative victory speech, Buchanan denounced Republicans, calling them a "dangerous" and "geographical" party that had unfairly attacked the South.[38] He also declared, "the object of my administration will be to destroy sectional party, North or South, and to restore harmony to the Union under a national and conservative government."[39] He set about this initially by feigning a sectional balance in his cabinet appointments.[40]

Presidency (1857–1861)

Inauguration

Buchanan was inaugurated on March 4, 1857, taking the oath of office from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. In his inaugural address, Buchanan committed himself to serving only one term, as his predecessor had done. He expressed abhorrence for the growing divisions over slavery and its status in the territories while saying that Congress should play no role in determining the status of slavery in the states or territories.[41] He also declared his support for popular sovereignty. Buchanan recommended that a federal slave code be enacted to protect the rights of slaveowners in federal territories. He alluded to a then-pending Supreme Court case, Dred Scott v. Sandford, which he said would permanently settle the issue of slavery. Dred Scott was a slave who was temporarily taken from a slave state to a free territory by his owner, John Sanford (the court misspelled his name). After Scott returned to the slave state, he filed a petition for his freedom based on his time in the free territory. After Buchanan's speech, the Dred Scott case was decided against Scott and in favor of his owner.[41]

Associate Justice Robert C. Grier leaked the decision in the "Dred Scott" case early to Buchanan. In his inaugural address, Buchanan declared that the issue of slavery in the territories would be "speedily and finally settled" by the Supreme Court.[42] According to historian Paul Finkelman:

Buchanan already knew what the Court was going to decide. In a major breach of Court etiquette, Justice Grier, who, like Buchanan, was from Pennsylvania, had kept the President-elect fully informed about the progress of the case and the internal debates within the Court. When Buchanan urged the nation to support the decision, he already knew what Taney would say. Republican suspicions of impropriety turned out to be fully justified.[43]

Historians agree that the Court decision was a major disaster because it dramatically inflamed tensions, leading to the Civil War.[44][45][46] In 2022, historian David W. Blight argues that the year 1857 was, "the great pivot on the road to disunion...largely because of the Dred Scott case, which stoked the fear, distrust and conspiratorial hatred already common in both the North and the South to new levels of intensity."[47]

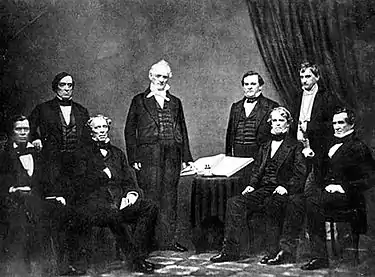

Cabinet and administration

| The Buchanan cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James Buchanan | 1857–1861 |

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of State | Lewis Cass | 1857–1860 |

| Jeremiah S. Black | 1860–1861 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Howell Cobb | 1857–1860 |

| Philip Francis Thomas | 1860–1861 | |

| John Adams Dix | 1861 | |

| Secretary of War | John B. Floyd | 1857–1860 |

| Joseph Holt | 1861 | |

| Attorney General | Jeremiah S. Black | 1857–1860 |

| Edwin Stanton | 1860–1861 | |

| Postmaster General | Aaron V. Brown | 1857–1859 |

| Joseph Holt | 1859–1860 | |

| Horatio King | 1861 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Isaac Toucey | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Jacob Thompson | 1857–1861 |

From left to right: Jacob Thompson, Lewis Cass, John B. Floyd, James Buchanan, Howell Cobb, Isaac Toucey, Joseph Holt and Jeremiah S. Black

As his inauguration approached, Buchanan sought to establish an obedient, harmonious cabinet to avoid the in-fighting that had plagued Andrew Jackson's administration.[48] He chose four Southerners and three Northerners, the latter of whom were all considered to be doughfaces (Southern sympathizers).[49] His objective was to dominate the cabinet, and he chose men who would agree with his views.[50] Concentrating on foreign policy, he appointed the aging Lewis Cass as Secretary of State. Buchanan's appointment of Southerners and their allies alienated many in the North, and his failure to appoint any followers of Stephen A. Douglas divided the party.[40] Outside of the cabinet, he left in place many of Pierce's appointments but removed a disproportionate number of Northerners who had ties to Democratic opponents Pierce or Douglas. In that vein, he soon alienated their ally and his vice president, Breckinridge; the latter therefore played little role in the administration.[51]

Judicial appointments

Buchanan appointed one Justice, Nathan Clifford, to the Supreme Court of the United States.[52] He appointed seven other federal judges to United States district courts. He also appointed two judges to the United States Court of Claims.[53]

Intervention in the Dred Scott case

Two days after Buchanan was sworn in as president, Chief Justice Taney delivered the Dred Scott decision, which denied the petitioner's request to be set free from slavery. The ruling broadly asserted that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories.[54] Prior to his inauguration, Buchanan had written to Justice John Catron in January 1857, inquiring about the outcome of the case and suggesting that a broader decision, beyond the specifics of the case, would be more prudent.[55] Buchanan hoped that a broad decision protecting slavery in the territories could lay the issue to rest, allowing him to focus on other issues.[56]

Catron, who was from Tennessee, replied on February 10, saying that the Supreme Court's Southern majority would decide against Scott, but would likely have to publish the decision on narrow grounds unless Buchanan could convince his fellow Pennsylvanian, Justice Robert Cooper Grier, to join the majority of the court.[57] Buchanan then wrote to Grier and prevailed upon him, providing the majority leverage to issue a broad-ranging decision sufficient to render the Missouri Compromise of 1820 unconstitutional.[58][59] Buchanan's letters were not then public; he was, however, seen at his inauguration in whispered conversation with the Chief Justice. When the decision was issued, Republicans began spreading the word that Taney had revealed to Buchanan the forthcoming result. Rather than destroying the Republican platform as Buchanan had hoped, the decision outraged Northerners who denounced it.[60]

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 began in the summer of that year, ushered in by the collapse of 1,400 state banks and 5,000 businesses. While the South escaped largely unscathed, numerous northern cities experienced drastic increases in unemployment. Buchanan agreed with the southerners who attributed the economic collapse to over-speculation.[61]

Reflecting his Jacksonian background, Buchanan's response was "reform not relief". While the government was "without the power to extend relief",[61] it would continue to pay its debts in specie, and while it would not curtail public works, none would be added. In hopes of reducing paper money supplies and inflation, he urged the states to restrict the banks to a credit level of $3 to $1 of specie and discouraged the use of federal or state bonds as security for bank note issues. The economy recovered in several years, though many Americans suffered as a result of the panic.[62] Buchanan had hoped to reduce the deficit, but by the time he left office the federal deficit stood at $17 million.[61]

Utah War

The Utah territory, settled in preceding decades by the Latter-day Saints and their leader Brigham Young, had grown increasingly hostile to federal intervention. Young harassed federal officers and discouraged outsiders from settling in the Salt Lake City area. In September 1857, the Utah Territorial Militia, associated with the Latter-day Saints, perpetrated the Mountain Meadows massacre against Arkansans headed for California. Buchanan was offended by the militarism and polygamous behavior of Young.[63]

Believing the Latter-day Saints to be in open rebellion, Buchanan in July 1857 sent Alfred Cumming, accompanied by the Army, to replace Young as governor. While the Latter-day Saints had frequently defied federal authority, some historians consider Buchanan's action was an inappropriate response to uncorroborated reports.[54] Complicating matters, Young's notice of his replacement was not delivered because the Pierce administration had annulled the Utah mail contract.[54] Young reacted to the military action by mustering a two-week expedition, destroying wagon trains, oxen, and other Army property. Buchanan then dispatched Thomas L. Kane as a private agent to negotiate peace. The mission succeeded, the new governor took office, and the Utah War ended. The President granted amnesty to inhabitants affirming loyalty to the government, and placed the federal troops at a peaceable distance for the balance of his administration.[64]

Transatlantic telegraph cable

Buchanan was the first recipient of an official telegram transmitted across the Atlantic. Following the dispatch of test and configuration telegrams, on August 16, 1858 Queen Victoria sent a 98-word message to Buchanan at his summer residence in the Bedford Springs Hotel in Pennsylvania, expressing hope that the newly laid cable would prove "an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded on their common interest and reciprocal esteem". Queen Victoria's message took 16 hours to send.[65][66]

Buchanan responded: "It is a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle. May the Atlantic telegraph, under the blessing of Heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship between the kindred nations, and an instrument destined by Divine Providence to diffuse religion, civilization, liberty, and law throughout the world."[67]

Bleeding Kansas

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 created the Kansas Territory and allowed the settlers there to decide whether to allow slavery. This resulted in violence between "Free-Soil" (antislavery) and pro-slavery settlers, which developed into the "Bleeding Kansas" period. The antislavery settlers, with the help of Northern abolitionists, organized a government in Topeka. The more numerous proslavery settlers, many from the neighboring slave state Missouri, established a government in Lecompton, giving the Territory two different governments for a time, with two distinct constitutions, each claiming legitimacy.

The admission of Kansas as a state required a constitution be submitted to Congress with the approval of a majority of its residents. Under President Pierce, a series of violent confrontations escalated over who had the right to vote in Kansas. The situation drew national attention, and some in Georgia and Mississippi advocated secession should Kansas be admitted as a free state. Buchanan chose to endorse the pro-slavery Lecompton government.[68]

Buchanan appointed Robert J. Walker to replace John W. Geary as Territorial Governor, and there ensued conflicting referendums from Topeka and Lecompton, where election fraud occurred. In October 1857, the Lecompton government framed the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution that agreed to a referendum limited solely to the slavery question. However, the vote against slavery, as provided by the Lecompton Convention, would still permit existing slaves, and all their issue, to be enslaved, so there was no referendum that permitted the majority anti-slavery residents to prohibit slavery in Kansas. As a result, anti-slavery residents boycotted the referendum since it did not provide a meaningful choice.[69]

Despite the protests of Walker and two former Kansas governors, Buchanan decided to accept the Lecompton Constitution. In a December 1857 meeting with Stephen Douglas, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, Buchanan demanded that all Democrats support the administration's position of admitting Kansas under the Lecompton Constitution. On February 2, he transmitted the Lecompton Constitution to Congress. He also transmitted a message that attacked the "revolutionary government" in Topeka, conflating them with the Mormons in Utah. Buchanan made every effort to secure congressional approval, offering favors, patronage appointments, and even cash for votes. The Lecompton Constitution won the approval of the Senate in March, but a combination of Know-Nothings, Republicans, and northern Democrats defeated the bill in the House. Rather than accepting defeat, Buchanan backed the 1858 English Bill, which offered Kansans immediate statehood and vast public lands in exchange for accepting the Lecompton Constitution. In August 1858, Kansans by referendum strongly rejected the Lecompton Constitution.[70]

The dispute over Kansas became the battlefront for control of the Democratic Party. On one side were Buchanan, most Southern Democrats, and the "doughfaces". On the other side were Douglas and most northern Democrats plus a few Southerners. Douglas's faction continued to support the doctrine of popular sovereignty, while Buchanan insisted that Democrats respect the Dred Scott decision and its repudiation of federal interference with slavery in the territories.[71] The struggle ended only with Buchanan's presidency. In the interim he used his patronage powers to remove Douglas sympathizers in Illinois and Washington, D.C., and installed pro-administration Democrats, including postmasters.[72]

1858 mid-term elections

Douglas's Senate term was coming to an end in 1859, with the Illinois legislature, elected in 1858, determining whether Douglas would win re-election. The Senate seat was the primary issue of the legislative election, marked by the famous debates between Douglas and his Republican opponent for the seat, Abraham Lincoln. Buchanan, working through federal patronage appointees in Illinois, ran candidates for the legislature in competition with both the Republicans and the Douglas Democrats. This could easily have thrown the election to the Republicans, and showed the depth of Buchanan's animosity toward Douglas.[73] In the end, Douglas Democrats won the legislative election and Douglas was re-elected to the Senate. In that year's elections, Douglas forces took control throughout the North, except in Buchanan's home state of Pennsylvania. Buchanan's support was otherwise reduced to a narrow base of southerners.[74][75]

The division between northern and southern Democrats allowed the Republicans to win a plurality of the House in the 1858 elections, and allowed them to block most of Buchanan's agenda. Buchanan, in turn, added to the hostility with his veto of six substantial pieces of Republican legislation.[76] Among these measures were the Homestead Act, which would have given 160 acres of public land to settlers who remained on the land for five years, and the Morrill Act, which would have granted public lands to establish land-grant colleges. Buchanan argued that these acts were unconstitutional.[77]

Foreign policy

Buchanan took office with an ambitious foreign policy, designed to establish U.S. hegemony over Central America at the expense of Great Britain.[78] He hoped to re-negotiate the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, which he thought limited U.S. influence in the region. He also sought to establish American protectorates over the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora, and most importantly, he hoped to achieve his long-term goal of acquiring Cuba. After long negotiations with the British, he convinced them to cede the Bay Islands to Honduras and the Mosquito Coast to Nicaragua. However, Buchanan's ambitions in Cuba and Mexico were largely blocked by the House of Representatives.[79]

Buchanan also considered buying Alaska from the Russian Empire, as a colony for Mormon settlers, but he and the Russians were unable to agree upon a price. In China, the administration won trade concessions in the Treaty of Tientsin.[80] In 1858, Buchanan ordered the Paraguay expedition to punish Paraguay for firing on the USS Water Witch, and the expedition resulted in a Paraguayan apology and payment of an indemnity.[79] The chiefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific, refusing to accept the rule of King Tamatoa V, unsuccessfully petitioned the United States to accept the islands under a protectorate in June 1858.[81]

Buchanan was offered a herd of elephants by King Rama IV of Siam, though the letter arrived after Buchanan's departure from office. As Buchanan's successor, Lincoln declined the King's offer, citing the unsuitable climate.[82] Other presidential pets included a pair of bald eagles and a Newfoundland dog.[83]

Covode Committee

In March 1860, the House impaneled the Covode Committee to investigate the administration for alleged impeachable offenses, such as bribery and extortion of representatives. The committee, three Republicans and two Democrats, was accused by Buchanan's supporters of being nakedly partisan; they charged its chairman, Republican Rep. John Covode, with acting on a personal grudge from a disputed land grant designed to benefit Covode's railroad company.[84] The Democratic committee members, as well as Democratic witnesses, were enthusiastic in their condemnation of Buchanan.[85][86]

The committee was unable to establish grounds for impeaching Buchanan; however, the majority report issued on June 17 alleged corruption and abuse of power among members of his cabinet. The report also included accusations from Republicans that Buchanan had attempted to bribe members of Congress, in connection with the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution of Kansas. The Democrats pointed out that evidence was scarce, but did not refute the allegations; one of the Democratic members, Rep. James Robinson, stated that he agreed with the Republicans, though he did not sign it.[86]

Buchanan claimed to have "passed triumphantly through this ordeal" with complete vindication. Republican operatives distributed thousands of copies of the Covode Committee report throughout the nation as campaign material in that year's presidential election.[87][88]

Election of 1860

As he had promised in his inaugural address, Buchanan did not seek re-election. He went so far as to tell his ultimate successor, "If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland [his home], you are a happy man."[89]

The 1860 Democratic National Convention convened in April of that year and, though Douglas led after every ballot, he was unable to win the two-thirds majority required. The convention adjourned after 53 ballots, and re-convened in Baltimore in June. After Douglas finally won the nomination, several Southerners refused to accept the outcome, and nominated Vice President Breckinridge as their own candidate. Douglas and Breckinridge agreed on most issues except the protection of slavery. Buchanan, nursing a grudge against Douglas, failed to reconcile the party, and tepidly supported Breckinridge. With the splintering of the Democratic Party, Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln won a four-way election that also included John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party. Lincoln's support in the North was enough to give him an Electoral College majority. Buchanan became the last Democrat to win a presidential election until Grover Cleveland in 1884.[90]

As early as October, the army's Commanding General, Winfield Scott, an opponent of Buchanan, warned him that Lincoln's election would likely cause at least seven states to secede from the union. He recommended that massive amounts of federal troops and artillery be deployed to those states to protect federal property, although he also warned that few reinforcements were available. Since 1857, Congress had failed to heed calls for a stronger militia and allowed the army to fall into deplorable condition.[91] Buchanan distrusted Scott and ignored his recommendations.[92] After Lincoln's election, Buchanan directed Secretary of War John B. Floyd to reinforce southern forts with such provisions, arms, and men as were available; however, Floyd persuaded him to revoke the order.[91]

Secession

With Lincoln's victory, talk of secession and disunion reached a boiling point, putting the burden on Buchanan to address it in his final speech to Congress on December 10. In his message, which was anticipated by both factions, Buchanan denied the right of states to secede but maintained the federal government was without power to prevent them. He placed the blame for the crisis solely on "intemperate interference of the Northern people with the question of slavery in the Southern States," and suggested that if they did not "repeal their unconstitutional and obnoxious enactments ... the injured States, after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the Government of the Union."[93][94] Buchanan's only suggestion to solve the crisis was "an explanatory amendment" affirming the constitutionality of slavery in the states, the fugitive slave laws, and popular sovereignty in the territories.[93] His address was sharply criticized both by the North, for its refusal to stop secession, and the South, for denying its right to secede.[95] Five days after the address was delivered, Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb resigned, as his views had become irreconcilable with the President's.[96]

South Carolina, long the most radical Southern state, seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860. However, Unionist sentiment remained strong among many in the South, and Buchanan sought to appeal to the Southern moderates who might prevent secession in other states. He proposed passage of constitutional amendments protecting slavery in the states and territories. He also met with South Carolinian commissioners in an attempt to resolve the situation at Fort Sumter, which federal forces remained in control of despite its location in Charleston, South Carolina. He refused to dismiss Interior Secretary Jacob Thompson after the latter was chosen as Mississippi's agent to discuss secession, and he refused to fire Secretary of War John B. Floyd despite an embezzlement scandal. Floyd ended up resigning, but not before sending numerous firearms to Southern states, where they eventually fell into the hands of the Confederacy. Despite Floyd's resignation, Buchanan continued to seek the advice of counselors from the Deep South, including Jefferson Davis and William Henry Trescot.[97]

Efforts were made in vain by Sen. John J. Crittenden, Rep. Thomas Corwin, and former president John Tyler to negotiate a compromise to stop secession, with Buchanan's support. Failed attempts were also made by a group of governors meeting in New York. Buchanan secretly asked President-elect Lincoln to call for a national referendum on the issue of slavery, but Lincoln declined.[98]

Despite the efforts of Buchanan and others, six more slave states seceded by the end of January 1861. Buchanan replaced the departed Southern cabinet members with John Adams Dix, Edwin M. Stanton, and Joseph Holt, all of whom were committed to preserving the Union. When Buchanan considered surrendering Fort Sumter, the new cabinet members threatened to resign, and Buchanan relented. On January 5, Buchanan decided to reinforce Fort Sumter, sending the Star of the West with 250 men and supplies. However, he failed to ask Major Robert Anderson to provide covering fire for the ship, and it was forced to return North without delivering troops or supplies. Buchanan chose not to respond to this act of war, and instead sought to find a compromise to avoid secession. He received a March 3 message from Anderson, that supplies were running low, but the response became Lincoln's to make, as the latter succeeded to the presidency the next day.[99]

Proposed constitutional amendment

On March 2, 1861, Congress approved an amendment to the United States Constitution that would shield "domestic institutions" of the states, including slavery, from the constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress. The proposed amendment was submitted to the state legislatures for ratification. Commonly known as the Corwin Amendment, it was never ratified by the requisite number of states.

Post-presidency (1861–1868)

The Civil War erupted within two months of Buchanan's retirement. He supported the Union and the war effort, writing to former colleagues that, "the assault upon Sumter was the commencement of war by the Confederate states, and no alternative was left but to prosecute it with vigor on our part."[102] He also wrote a letter to his fellow Pennsylvania Democrats, urging them to "join the many thousands of brave & patriotic volunteers who are already in the field."[102]

Buchanan was dedicated to defending his actions prior to the Civil War, which was referred to by some as "Buchanan's War".[102] He received threatening letters daily, and stores displayed Buchanan's likeness with the eyes inked red, a noose drawn around his neck and the word "TRAITOR" written across his forehead. The Senate proposed a resolution of condemnation which ultimately failed, and newspapers accused him of colluding with the Confederacy. His former cabinet members, five of whom had been given jobs in the Lincoln administration, refused to defend Buchanan publicly.[103]

Buchanan became distraught by the vitriolic attacks levied against him, and fell sick and depressed. In October 1862, he defended himself in an exchange of letters with Winfield Scott, published in the National Intelligencer.[104] He soon began writing his fullest public defense, in the form of his memoir Mr. Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of Rebellion, which was published in 1866.[105]

Soon after the publication of the memoir, Buchanan caught a cold in May 1868, which quickly worsened due to his advanced age. He died on June 1, 1868, of respiratory failure at the age of 77 at his home at Wheatland. He was interred in Woodward Hill Cemetery in Lancaster.[105]

Political views

Buchanan was often considered by anti-slavery northerners a "doughface", a northerner with pro-southern principles.[106] Shortly after his election, he said that the "great object" of his administration was "to arrest, if possible, the agitation of the Slavery question in the North and to destroy sectional parties".[106] Although Buchanan was personally opposed to slavery,[19] he believed that the abolitionists were preventing the solution to the slavery problem. He stated, "Before [the abolitionists] commenced this agitation, a very large and growing party existed in several of the slave states in favor of the gradual abolition of slavery; and now not a voice is heard there in support of such a measure. The abolitionists have postponed the emancipation of the slaves in three or four states for at least half a century."[107] In deference to the intentions of the typical slaveholder, he was willing to provide the benefit of the doubt. In his third annual message to Congress, the president claimed that the slaves were "treated with kindness and humanity. ... Both the philanthropy and the self-interest of the master have combined to produce this humane result."[108]

Buchanan thought restraint was the essence of good self-government. He believed the constitution comprised "... restraints, imposed not by arbitrary authority, but by the people upon themselves and their representatives. ... In an enlarged view, the people's interests may seem identical, but to the eye of local and sectional prejudice, they always appear to be conflicting ... and the jealousies that will perpetually arise can be repressed only by the mutual forbearance which pervades the constitution."[109] Regarding slavery and the Constitution, he stated: "Although in Pennsylvania we are all opposed to slavery in the abstract, we can never violate the constitutional compact we have with our sister states. Their rights will be held sacred by us. Under the constitution it is their own question; and there let it remain."[107]

One of the prominent issues of the day was tariffs.[110] Buchanan was conflicted by free trade as well as prohibitive tariffs, since either would benefit one section of the country to the detriment of the other. As a senator from Pennsylvania, he said: "I am viewed as the strongest advocate of protection in other states, whilst I am denounced as its enemy in Pennsylvania."[111]

Buchanan was also torn between his desire to expand the country for the general welfare of the nation, and to guarantee the rights of the people settling particular areas. On territorial expansion, he said, "What, sir? Prevent the people from crossing the Rocky Mountains? You might just as well command the Niagara not to flow. We must fulfill our destiny."[112] On the resulting spread of slavery, through unconditional expansion, he stated: "I feel a strong repugnance by any act of mine to extend the present limits of the Union over a new slave-holding territory." For instance, he hoped the acquisition of Texas would "be the means of limiting, not enlarging, the dominion of slavery."[112]

Personal life

In 1818, Buchanan met Anne Caroline Coleman at a grand ball in Lancaster, and the two began courting. Anne was the daughter of wealthy iron manufacturer Robert Coleman. She was also the sister-in-law of Philadelphia judge Joseph Hemphill, one of Buchanan's colleagues. By 1819, the two were engaged, but spent little time together. Buchanan was busy with his law firm and political projects during the Panic of 1819, which took him away from Coleman for weeks at a time. Rumors abounded, as some suggested that he was marrying her only for money; others said he was involved with other (unidentified) women. Letters from Coleman revealed she was aware of several rumors.[113] She broke off the engagement, and soon afterward, on December 9, 1819, suddenly died.[114] Buchanan wrote to her father for permission to attend the funeral, which was refused.[115]

After Coleman's death, Buchanan never courted another woman. At the time of her funeral, he said that, "I feel happiness has fled from me forever."[116] During his presidency, an orphaned niece, Harriet Lane, whom he had adopted, served as official White House hostess.[117] There was an unfounded rumor that he had an affair with President Polk's widow, Sarah Childress Polk.[118]

Buchanan's lifelong bachelorhood after Anne Coleman's death has drawn interest and speculation.[119] Some conjecture that Anne's death merely served to deflect questions about Buchanan's sexuality and bachelorhood.[116] Several writers have surmised that he was homosexual, including James W. Loewen,[120] Robert P. Watson, and Shelley Ross.[121][122] One of his biographers, Jean Baker, suggests that Buchanan was celibate, if not asexual.[123]

Buchanan had a close relationship with William Rufus King, which became a popular target of gossip. King was an Alabama politician who briefly served as vice president under Franklin Pierce. Buchanan and King lived together in a Washington boardinghouse and attended social functions together from 1834 until 1844. Such a living arrangement was then common, though King once referred to the relationship as a "communion".[118] Andrew Jackson called King "Miss Nancy" and Buchanan's Postmaster General Aaron V. Brown referred to King as Buchanan's "better half", "wife", and "Aunt Fancy".[124][125][126] Loewen indicated that Buchanan late in life wrote a letter acknowledging that he might marry a woman who could accept his "lack of ardent or romantic affection".[127][128] Catherine Thompson, the wife of cabinet member Jacob Thompson, later noted that "there was something unhealthy in the president's attitude."[118] King died of tuberculosis shortly after Pierce's inauguration, four years before Buchanan became president. Buchanan described him as "among the best, the purest and most consistent public men I have known".[118] Biographer Baker opines that both men's nieces may have destroyed correspondence between the two men. However, she believes that their surviving letters illustrate only "the affection of a special friendship".[119]

Legacy

Historical reputation

Though Buchanan predicted that "history will vindicate my memory,"[129] historians have criticized Buchanan for his unwillingness or inability to act in the face of secession. Historical rankings of presidents of the United States without exception place Buchanan among the least successful presidents.[130] When scholars are surveyed, he ranks at or near the bottom in terms of vision/agenda-setting,[131] domestic leadership, foreign policy leadership,[132] moral authority,[133] and positive historical significance of their legacy.[134] According to surveys taken by American scholars and political scientists between 1948 and 1982, Buchanan ranks every time among the worst presidents of the United States, alongside Grant, Harding, Fillmore and Nixon.[135]

Buchanan biographer Philip S. Klein focused in 1962, during the Civil Rights movement, upon challenges Buchanan faced:

Buchanan assumed leadership ... when an unprecedented wave of angry passion was sweeping over the nation. That he held the hostile sections in check during these revolutionary times was in itself a remarkable achievement. His weaknesses in the stormy years of his presidency were magnified by enraged partisans of the North and South. His many talents, which in a quieter era might have gained for him a place among the great presidents, were quickly overshadowed by the cataclysmic events of civil war and by the towering Abraham Lincoln.[136]

Biographer Jean Baker is less charitable to Buchanan, saying in 2004:

Americans have conveniently misled themselves about the presidency of James Buchanan, preferring to classify him as indecisive and inactive ... In fact Buchanan's failing during the crisis over the Union was not inactivity, but rather his partiality for the South, a favoritism that bordered on disloyalty in an officer pledged to defend all the United States. He was that most dangerous of chief executives, a stubborn, mistaken ideologue whose principles held no room for compromise. His experience in government had only rendered him too self-confident to consider other views. In his betrayal of the national trust, Buchanan came closer to committing treason than any other president in American history.[137]

Other historians, such as Robert May, argued that his politics were "anything but pro-slavery",[138][139][140] nevertheless, a very negative view is to be found in Michael Birkner's works about Buchanan.[141][142] For Lori Cox Han, he ranks among scholars "as either the worst president in [American] history or as part of a lowest ranking failure category".[143]

Memorials

A bronze and granite memorial near the southeast corner of Washington, D.C.'s Meridian Hill Park was designed by architect William Gorden Beecher and sculpted by Maryland artist Hans Schuler. It was commissioned in 1916 but not approved by the U.S. Congress until 1918, and not completed and unveiled until June 26, 1930. The memorial features a statue of Buchanan, bookended by male and female classical figures representing law and diplomacy, with engraved text reading: "The incorruptible statesman whose walk was upon the mountain ranges of the law," a quote from a member of Buchanan's cabinet, Jeremiah S. Black.[144]

An earlier monument was constructed in 1907–1908 and dedicated in 1911, on the site of Buchanan's birthplace in Stony Batter, Pennsylvania. Part of the original 18.5-acre (75,000 m2) memorial site is a 250-ton pyramid structure that stands on the site of the original cabin where Buchanan was born. The monument was designed to show the original weathered surface of the native rubble and mortar.[145]

Three counties are named in his honor, in Iowa, Missouri, and Virginia. Another in Texas was christened in 1858 but renamed Stephens County, after the newly elected Vice President of the Confederate States of America, Alexander Stephens, in 1861.[146] The city of Buchanan, Michigan, was also named after him.[147] Several other communities are named after him: the unincorporated community of Buchanan, Indiana, the city of Buchanan, Georgia, the town of Buchanan, Wisconsin, and the townships of Buchanan Township, Michigan, and Buchanan, Missouri.

James Buchanan High School is a small, rural high school located on the outskirts of his childhood hometown, Mercersburg, Pennsylvania.

Popular culture depictions

Buchanan and his legacy are central to the film Raising Buchanan (2019). He is portrayed by René Auberjonois.[148]

See also

References

- Ellis, Franklin; Evans, Samuel (1883). History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Everts & Peck. p. 214.

- Curtis, George Ticknor (1883). Life of James Buchanan, Fifteenth President of the United States. Vol. 1. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-62376-821-8.

- Olausson, Lena; Sangster, Catherine (2006). Oxford BBC Guide to Pronunciation. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-19-280710-2.

- Baker 2004, pp. 9–12.

- Baker 2004, pp. 12.

- Klein 1962, pp. 9–12.

- Baker 2004, pp. 13–16.

- Curtis 1883, p. 22.

- Baker 2004, p. 18.

- Baker 2004, pp. 17–18.

- Klein 1962, p. 27.

- Montgomery, Thomas Lynch (1907). Pennsylvania Archives: Sixth Series. Vol. VII. Harrisburg, PA: Harrisburg Publishing Company. p. 906.

- O'Brien, Marco. "Military trivia facts". Military.com. Military Advantage, a division of Monster Worldwide. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

Only one President (James Buchanan) served as an enlisted person in the military and did not go on to become an officer.

- Moody, Wesley (2016). The Battle of Fort Sumter: The First Shots of the American Civil War. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-3176-6718-6 – via Google Books.

- Klein, Philip Shriver; Hoogenboom, Ari (1980). A History of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-271-01934-5.

- Baker 2004, pp. 23–30.

- O'Leary, Derek Kane (March 6, 2023). "James Buchanan's 1832 Mission to the Tsar, the Plight of Poland, and the Limits of America's Revolutionary Legacy in Jacksonian Foreign Policy". Age of Revolutions. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- Baker 2004, pp. 30–31.

- Baker 2004, p. 30.

- "Letter from James Buchanan to Reuel William" (U.S. Senator Buchanan discusses David Porter and the 1838 gubernatorial election in Pennsylvania). Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Dickinson College, Archives & Special Collections, retrieved online December 30, 2022.

- "Governor David Rittenhouse Porter" (biography). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, retrieved online December 30, 2022.

- "Governor Joseph Ritner" (biography). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, retrieved online December 30, 2022.

- Secretary of the United States Senate. "Gag rule". United States Senate. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- Baker 2004, p. 32.

- Baker 2004, pp. 30–38.

- Baker 2004, pp. 38–40.

- Baker 2004, pp. 38–43.

- Baker 2004, pp. 43–51.

- Klein 1962, p. 210, 415.

- Baker 2004, pp. 51–58.

- Baker 2004, pp. 58–65.

- McPherson 1988, p. 110.

- Tucker 2009, pp. 456–57.

- Baker 2004, pp. 67–68.

- Klein 1962, pp. 248–252.

- Baker 2004, p. 69.

- Baker 2004, pp. 69–70.

- Baker 2004, pp. 70–73.

- Klein 1962, pp. 261–262.

- Baker 2004, pp. 77–80.

- Baker 2004, pp. 80–83, 85.

- James Buchanan, "Inaugural Address," Washington, D.C., March 4, 1857.

- Finkelman, Paul (2007). "Scott v. Sandford: The Court's most dreadful case and how it changed history". Chicago-Kent Law Review. 82: 3–48.

- Carrafiello, Michael L. (Spring 2010). "Diplomatic Failure: James Buchanan's Inaugural Address". Pennsylvania History. 77 (2): 145–165. doi:10.5325/pennhistory.77.2.0145. JSTOR 10.5325/pennhistory.77.2.0145.

- Wallance, Gregory J. (2006). "The Lawsuit That Started the Civil War". Civil War Times Illustrated. Vol. 45, no. 2. pp. 47–50.

- Alexander, Roberta (2007). "Dred Scott: The Decision That Sparked a Civil War". Northern Kentucky Law Review. 34 (4): 643–662.

- Blight, David W. (December 21, 2022). "Was the Civil War Inevitable?". The New York Times.

- Baker 2004, p. 77.

- Baker 2004, p. 78.

- Baker 2004, p. 79.

- Baker 2004, pp. 86–88.

- "Nathan Clifford, 1858–1881". The Supreme Court Historical Society. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- "Judges of the United States Courts". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- Klein 1962, p. 316.

- Klein 1962, pp. 271–272.

- Baker 2004, pp. 83–84.

- Hall 2001, p. 566.

- Potter 1976, p. 287.

- Baker 2004, p. 85.

- Baker 2004, pp. 85–86.

- Baker 2004, p. 90.

- Klein 1962, pp. 314–315.

- Baker 2004, pp. 90–91.

- Klein 1962, p. 317.

- Jim Al-Khalili. Shock and Awe: The Story of Electricity, Ep. 2 "The Age of Invention". October 13, 2011, BBC TV, Using Chief Engineer Bright's original notebook. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- Jesse Ames Spencer (1866). "Chapter IX. 1857–1858. Opening of Buchanan's Administration" (Digitised eBook). 'THE QUEEN'S MESSAGE' and 'THE PRESIDENT'S REPLY' (full wording). p. 542. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Baker 2004, pp. 93–98.

- Baker 2004, pp. 97–100.

- Baker 2004, pp. 100–105.

- Baker 2004, pp. 120–121.

- Chadwick 2008, p. 91.

- Chadwick 2008, p. 117.

- Potter 1976, pp. 297–327.

- Klein 1962, pp. 286–299.

- Klein 1962, p. 312.

- Baker 2004, pp. 117–118.

- Smith 1975, pp. 69–70.

- Baker 2004, pp. 107–112.

- Smith 1975, pp. 74–75.

- Flude 2012, pp. 393–413.

- "Lincoln Rejects the King of Siam's Offer of Elephants". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- "Top Ten Strangest Presidential Pets". PetMD. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- Klein 1962, p. 338.

- Klein 1962, pp. 338–9.

- Grossman 2003, p. 78.

- Baker 2004, pp. 114–118.

- Klein 1962, p. 339.

- Klein 1962.

- Baker 2004, pp. 118–120.

- Klein 1962, pp. 356–358.

- Baker 2004, pp. 76, 133.

- Buchanan (1860)

- "James Buchanan, Fourth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union, December 3, 1860". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- Klein 1962, p. 363.

- "The Resignation of Secretary Cobb. The Correspondence". The New York Times. December 14, 1860.

- Baker 2004, pp. 123–134.

- Klein 1962, pp. 381–387.

- Baker 2004, pp. 135–140.

- "Today in History: May 11". Library of Congress. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- "Oregon". A+E Networks Corp. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Birkner, Michael (September 20, 2005). "Buchanan's Civil War". Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Klein 1962, pp. 408–413.

- Klein 1962, pp. 417–418.

- Baker 2004, pp. 142–143.

- Stampp 1990, p. 48.

- Klein 1962, p. 150.

- "Third Annual Message (December 19, 1859)". The Miller Center at the University of Virginia. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- Klein 1962, p. 143.

- Jurinski, pp. 16–17.

- Klein 1962, p. 144.

- Klein 1962, p. 147.

- Boertlein, John (2010). Presidential Confidential: Sex, Scandal, Murder and Mayhem in the Oval Office. Cincinnati, Ohio: Clerisy Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-57860-361-9.

- Klein 1955.

- Sandburg, Carl (1939). Abraham Lincoln: The War Years. Vol. 1. New York City: Harcourt, Brace & Company. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-299-11525-5.

- Dunn, Charles (1999). The Scarlet Thread of Scandal: Morality and the American Presidency. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8476-9606-2.

- "Harriet Lane". The White House. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- Watson 2012, p. 247

- Baker 2004, pp. 25–26.

- Loewen, James W. (1999). Lies across America: What our Historic Sites get Wrong. New York City: The New Press. ISBN 978-0-684-87067-0.

- Ross 1988, pp. 86–91.

- Watson 2012, p. 233.

- Baker 2004, p. 26.

- Neaman, Judith S.; Silver, Carole G. (1995). The Wordsworth Book of Euphemisms. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 9781853263392.

- Loewen 1999 p. 367

- Baker 2004, p. 75.

- Loewen 1999 pp. 367–370

- Loewen, James (2009). Lies Across America. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 342–45.

- "Buchanan's Birthplace State Park". Pennsylvania State Parks. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on May 6, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- "C-SPAN Survey on Presidents 2021: Total Scores/Overall Rankings". C-Span. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "C-SPAN Survey on Presidents 2021: Vision / Setting an Agenda". C-span. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "C-SPAN Survey on Presidents 2021: International Relations". C-span. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "C-SPAN Survey on Presidents 2021: Moral Authority". C-span. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "The top US presidents: First poll of UK experts". BBC News. January 17, 2011.

- Murphy, Arthur B. (1984). "Evaluating the Presidents of the United States". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 14 (1): 117–126. JSTOR 27550039.

- Klein 1962, p. 429.

- Baker 2004, pp. 141.

- Barney, William L. (1997). "Review of The Origins of the American Civil War". The Journal of Southern History. 63 (4): 880–882. doi:10.2307/2211745. JSTOR 2211745.

- James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s: A Panel Discussion (Pennsylvania State University ed.). Gettysburg: Pennsylvania State University. 1991.

- May, Robert E. (2013). Slavery, race and conquest in the tropics: Lincoln, Douglas, and the future of Latin America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13252-7.

- Birkner, Michael J., ed. (1996). James Buchanan and the political crisis of the 1850s. Selinsgrove, Pa.: Susquehanna Univ. Press [u.a.] ISBN 978-0-945636-89-2.

- Crouthamel, James L (July 1996). "Birkner, ed., 'James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s' (Book Review)". New York History. 77 (3): 350. ProQuest 1297186054.

- Han, Lori Cox, ed. (2018). Hatred of America's presidents: personal attacks on the White House from Washington to Trump. Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado: ABC-CLIO, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4408-5436-1.

- Strauss 2016, p. 213.

- "Buchanan's Birthplace State Park". Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- Beatty 2001, p. 310.

- Hoogterp, Edward (2006). West Michigan Almanac, p. 168. The University of Michigan Press & The Petoskey Publishing Company.

- "Raising Buchanan on IMDB". IMDb. April 12, 2019.

Works cited

- Baker, Jean H. (2004). James Buchanan. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6946-4.

- Beatty, Michael A. (2001). County Name Origins of the United States. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1025-5.

- Chadwick, Bruce (2008). 1858: Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant and the War They Failed to See. Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 978-1402209413.

- Curtis, George Ticknor (1883). Life of James Buchanan: Fifteenth President of the United States. Vol. 2. Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-1-4047-5444-7.

- Flude, Anthony G. (March 2012). "Manuscript XXIII: A Raiatean Petition for American Protection". The Journal of Pacific History. Canberra: Australian National University. 47 (1): 111–121. doi:10.1080/00223344.2011.632982. OCLC 785915823. S2CID 159847026.

- Grossman, Mark (2003). Political Corruption in America: An Encyclopedia of Scandals, Power, and Greed. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-060-4.

- Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court justices: a biographical dictionary. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-1176-8.

- Klein, Philip Shriver (December 1955). "The Lost Love of a Bachelor President". American Heritage Magazine. 7 (1). Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Klein, Philip S. (1962). President James Buchanan: A Biography (1995 ed.). American Political Biography Press. ISBN 978-0-945707-11-0.

- Klein, Philip Shriver; Hoogenboom, Ari (1980). A History of Pennsylvania. Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01934-5.

- Jurinski, James John (2012). Tax Reform: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-322-4.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974390-2.

- Potter, David Morris (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-090524-8. Pulitzer prize.

- Ross, Shelley (1988). Fall from Grace: Sex, Scandal, and Corruption in American Politics from 1702 to the Present. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-35381-8.

- Smith, Elbert (1975). The Presidency of James Buchanan. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0132-5.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. (1990). America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-987947-2.

- Strauss, Robert (2016). Worst. President. Ever.: James Buchanan, the POTUS Rating Game, and the Legacy of the Least of the Lesser Presidents. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4930-2484-1.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-952-8.

- Watson, Robert P. (2012). Affairs of State: The Untold History of Presidential Love, Sex, and Scandal, 1789–1900. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-1836-9.

Further reading

Secondary sources

- Balcerski, Thomas J. (2019). Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-091460-8. Review: Cleves, Rachel Hope (2021). "Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King by Thomas J. Balcerski, and: The Worlds of James Buchanan and Thaddeus Stevens: Place, Personality, and Politics in the Civil War Era ed. by Michael J. Birkner, Randall M. Miller and John W. Quist (review)". The Journal of the Civil War Era. 11 (1): 108–111. doi:10.1353/cwe.2021.0008. Project MUSE 783011.

- Balcerski, Thomas J. (2016). "Harriet Rebecca Lane Johnston". A Companion to First Ladies. pp. 197–213. doi:10.1002/9781118732250.ch12. ISBN 978-1-118-73225-0.

- Binder, Frederick Moore (September 1992). "James Buchanan: Jacksonian Expansionist". The Historian. 55 (1): 69–84. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1992.tb00886.x.

- Binder, Frederick Moore (1994). James Buchanan and the American Empire. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-0-945636-64-9.

- Birkner, Michael J., ed. (1996). James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-0-945636-89-2.

- Birkner, Michael J., et al. eds. The Worlds of James Buchanan and Thaddeus Stevens: Place, Personality, and Politics in the Civil War Era (Louisiana State University Press, 2019)

- Horrocks, Thomas A. President James Buchanan and the Crisis of National Leadership (Hauppauge, N.Y.: Nova Science Publisher's, Inc., 2011.

- Meerse, David E. (1995). "Buchanan, the Patronage, and the Lecompton Constitution: A Case Study". Civil War History. 41 (4): 291–312. doi:10.1353/cwh.1995.0017. S2CID 143955378.

- Nevins, Allan (1950). The Emergence of Lincoln: Douglas, Buchanan, and Party Chaos, 1857–1859. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-10415-7.

- Nichols, Roy Franklin; The Democratic Machine, 1850–1854 (1923), detailed narrative; online Archived May 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Quist, John W.; Birkner, Michael J., eds. (2013). James Buchanan and the Coming of the Civil War. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-4426-2.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1906). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the End of the Roosevelt Administration. Vol. 2. Macmillan.

- Rosenberger, Homer T. (1957). "Inauguration of President Buchanan a Century Ago". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 57/59: 96–122. JSTOR 40067189.

- Silbey, Joel H., ed. (2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861. doi:10.1002/9781118609330. ISBN 978-1-4443-3912-3.

- Updike, John (2013) [1974]. Buchanan Dying: A Play. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8129-8491-0., fictional.

- "2. Douglas and Goliath". Stephen Douglas. 1971. pp. 12–54. doi:10.7560/701182-005. ISBN 978-0-292-74198-0. S2CID 243794146.

Primary sources

- Buchanan, James. Fourth Annual Message to Congress. Archived September 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine (December 3, 1860).

- Buchanan, James. Mr Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion (1866)

- National Intelligencer (1859)

External links

- United States Congress. "James Buchanan (id: B001005)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- James Buchanan: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- The James Buchanan papers, spanning the entirety of his legal, political and diplomatic career, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- University of Virginia article: Buchanan biography

- Wheatland

- James Buchanan at Tulane University

- Essay on James Buchanan and his presidency from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Buchanan's Birthplace State Park, Franklin County, Pennsylvania

- "Life Portrait of James Buchanan", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, June 21, 1999

Primary sources

- Works by James Buchanan at Project Gutenberg

- Works by James Buchanan at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about James Buchanan at Internet Archive

- James Buchanan Ill with Dysentery Before Inauguration: Original Letters Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Mr. Buchanans Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion. President Buchanans memoirs.

- Inaugural Address

- Fourth Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1860