President for life

President for life is a title assumed by or granted to some presidents to extend their tenure up until their death. The title sometimes confers on the holder the right to nominate or appoint a successor. The usage of the title of "president for life" rather than a traditionally autocratic title, such as that of a monarch, implies the subversion of liberal democracy by the titleholder (although republics need not be democratic per se). Indeed, sometimes a president for life can proceed to establish a self-proclaimed monarchy, such as Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe in Haiti.

Similarity to a monarch

A president for life may be regarded as a de facto monarch. In fact, other than the title, political scientists often face difficulties in differentiating a state ruled by a president for life (especially one who inherits the job from a family dictatorship) and a monarchy – indeed, Samoa's long-serving President for life, Malietoa Tanumafili II, was frequently and mistakenly referred to as King. In his proposed plan for government at the United States Constitutional Convention Alexander Hamilton proposed that the chief executive be a governor elected to serve for good behavior, acknowledging that such an arrangement might be seen as an elective monarchy. It was for that very reason that the proposal was rejected. A notable difference between a monarch and a president-for-life is that the successor of the president does not necessarily possess a life-long term, like in Turkmenistan and Samoa.

Most leaders who have proclaimed themselves president for life have not in fact successfully gone on to serve a life term. Most have been deposed long before their death while others achieve a lifetime presidency by being assassinated while in office. However, some have managed to rule until their (natural) deaths, including José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia of Paraguay, Alexandre Pétion of Haiti, Rafael Carrera of Guatemala, François Duvalier of Haiti, Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, and Saparmurat Niyazov of Turkmenistan. Others made unsuccessful attempts to have themselves named president for life, such as Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire in 1972.[1]

People frequently cited as being examples of Presidents for Life include very long-serving authoritarian or totalitarian presidents such as Zaire's Mobutu, North Korea's Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, Bulgaria's Todor Zhivkov, Romania's Nicolae Ceaușescu, Syria's Hafez al-Assad, Indonesia's Suharto, Nationalist China's Chiang Kai-shek, Communist China's Mao Zedong, Iraq's Saddam Hussein, Russia's Vladimir Putin, Belarus's Alexander Lukashenko and Vietnam's Hồ Chí Minh. They were never officially granted life terms and, in fact, underwent periodic renewals of mandate that were in some cases sham elections.[2][3][4] Following the abolition of term limits for the President of the People's Republic of China, the current President Xi Jinping has been identified by some observers as a potential or aspiring President for life, who is also the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, the de facto highest position in China and already without term limit. According to reports from US-funded Freedom House, official election results in Belarus and Russia show implausibly high levels of support (in some cases, unanimous support).[5][6]

In popular culture

In the film Escape from L.A., the President played by Cliff Robertson is given a life term by a constitutional amendment after an earthquake ravages Los Angeles and leads to the President's shocking electoral victory. At the end of the film, Snake played by Kurt Russell puts an end to his regime when he uses an EMP aiming device remote ending all governments including that of his dictatorship.

List of leaders who became president for life

Note: The first date listed in each entry is the date of proclamation of the status as President for Life.

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Country | Title | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

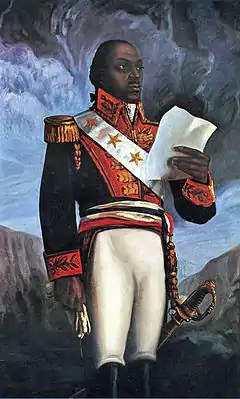

| Toussaint Louverture (1743–1803) | Governor for Life of Saint-Domingue | 1801 | 1802 | Deposed 1802, died in exile in France 1803. | |

| Henri Christophe (1767–1820) | President for Life of Haiti (Northern) | 1807 | 1811 | Became King 1811, committed suicide while reigning 1820. | |

| José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1766–1840) | Perpetual Supreme Dictator of Paraguay | 1816 | 1840 | Died in office 1840. | |

.jpg.webp) | Alexandre Pétion (1770–1818) | President for Life of Haiti (Southern) | 1816 | 1818 | Died in office 1818. | |

| Jean-Pierre Boyer (1776–1850) | President for Life of Haiti | 1818 | 1843 | Became President for Life immediately upon assuming the office because Alexandre Pétion's constitution provided for a life presidency for all his successors, deposed 1843, died 1850. | |

| Antonio López de Santa Anna (1794–1876) | President for Life of Mexico | 1853 | 1855 | Resigned 1855, died 1876. | |

| Rafael Carrera (1814–1865) | President for Life of Guatemala | 1854 | 1865 | Died in office 1865. | |

| Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) | Chancellor and Führer for life | 1934 | 1945 | Committed suicide in office 1945. | |

.jpg.webp) | Tupua Tamasese Meaʻole (1905–1963) | O le Ao o le Malo for Life of Samoa | 1962 | 1963 | Died in office 1963, elected to serve alongside Tanumafili II (see below). The position of O le Ao o le Malo (head of state) is ceremonial; executive power is exercised by the Prime Minister, and Samoa is a parliamentary democracy.[7] | |

.jpg.webp) | Malietoa Tanumafili II (1913–2007) | 2007 | Died in office 2007, elected to serve alongside Meaʻole (see above).[7] | |||

| Sukarno (1901–1970) | Supreme Commander, Great Leader of Revolution, Mandate Holder of the Provisional People's Consultative Assembly, and President for Life of Indonesia | 1963 | 1966 | Designated as President for Life according to the Ketetapan MPRS No. III/MPRS/1963,[8] life term removed 1966, deposed 1967, died under house arrest 1970. | |

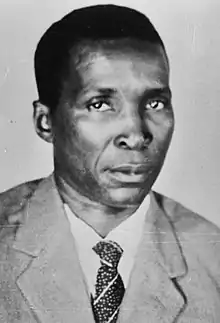

.jpg.webp) | Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972) | President for Life of Ghana | 1964 | 1966 | Ousted in 1966, died in exile in Romania 1972. | |

.jpg.webp) | François "Papa Doc" Duvalier (1907–1971) | President for Life of Haiti | 1964 | 1971 | Died in office 1971, named his son as his successor (see below).[9] | |

.jpg.webp) | Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier (1951–2014) | 1971 | 1986 | Named by his father as successor (see above), deposed 1986, died 2014. | ||

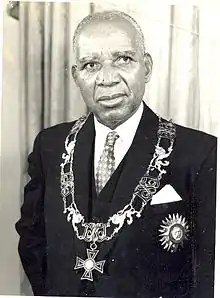

| Hastings Banda (1898–1997) | President for Life of Malawi | 1971 | 1993 | Life term removed 1993, voted out of office 1994, died 1997. | |

| Jean-Bédel Bokassa (1921–1996) | President for Life of the Central African Republic | 1972 | 1976 | Became Emperor 1976 (crowned 1977), deposed 1979, died 1996. | |

| Francisco Macías Nguema (1924–1979) | President for Life of Equatorial Guinea | 1972 | 1979 | Deposed and executed 1979. | |

| Ferdinand Marcos (1917–1989) | President for Life of the Philippines[Note 1] | 1973 | 1981 | Life term removed in 1981, Deposed in 1986, replaced by Corazon Aquino, died in exile in Honolulu, Hawaii, United States in 1989. | |

| Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980) | President for Life of Yugoslavia | 1974 | 1980 | Appointed as President for Life according to the 1974 Constitution, died in office 1980. | |

| Habib Bourguiba (1903–2000) | President for Life of Tunisia | 1975 | 1987 | Deposed 1987, died under house arrest 2000. | |

_gtfy.00132_(cropped).jpg.webp) | Idi Amin (1925–2003) | President for Life of Uganda | 1976 | 1979 | Deposed 1979, died in exile in Saudi Arabia 2003. | |

| Lennox Sebe (1926–1994) | ( | President for Life of Ciskei | 1983 | 1990 | Deposed 1990, died 1994. |

| Saparmurat Niyazov (1940–2006) | President for Life of Turkmenistan | 1999 | 2006 | Died in office 2006. |

Notes

- Although he never formally claimed the title of President For Life, Marcos used a declaration of martial law (Proclamation No. 1081) to extend his mandate indefinitely beyond the term limits set by the Philippine Constitution of 1935. This was formally done through promulgating a new Constitution in 1973, whose transitional provisions gave Marcos an interim presidential term that would only end when "he calls upon the Interim National Assembly to elect the interim President [who would succeed him]". By the time Marcos made use of this provision in 1981, the constitution was amended to re-establish direct presidential elections. In the ensuing 1981 Philippine presidential election and referendum, Marcos was re-elected for a term of six years.

References

- Crawford Young and Thomas Turner, The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State, p. 211

- Snyder, Timothy (3 April 2018). The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. p. 43. ISBN 9780525574460.

- Chivers, C.J. (February 8, 2008). "European Group Cancels Mission to Observe Russian Election, Citing Restrictions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- Kara-Murza, Vladimir Vladimirovich. "As the Kremlin Tightens the Screws, It Invites Popular Revolt". Spotlight on Russia. World Affairs Journal. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Russia". Freedom in the World 2020. Freedom House. 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

Kremlin is able to manipulate elections and suppress genuine dissent.

- "Belarus". Freedom in the World 2020. Freedom House. 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

Belarus is an authoritarian police state in which elections are openly rigged and civil liberties are curtailed. [...] Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) monitors noted that longstanding deficiencies in Belarusian elections were unaddressed, including a restrictive legal framework, media coverage that fails to help voters make informed choices, irregularities in vote counting, and restrictions on free expression and assembly during the campaign period. The group concluded that the elections fell considerably short of democratic standards.

- "Constitution of the Independent State of Western Samoa 1960". University of the South Pacific. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- "Ketetapan MPRS No. III/MPRS/1963". hukumonline.com.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought: Abol-impe. Oxford University Press. 2010-01-01. p. 328. ISBN 9780195334739.

Further reading

- Mngomezulu, Bhekithemba Richard (2013). The President for Life Pandemic: Kenya, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Zambia and Malawi. Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd. ISBN 9781909112315.

External links

- The List: Presidents for Life // Foreign Policy, November 5, 2007