Population informatics

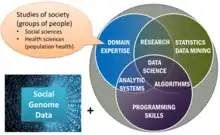

The field of population informatics is the systematic study of populations via secondary analysis of massive data collections (termed "big data") about people. Scientists in the field refer to this massive data collection as the social genome, denoting the collective digital footprint of our society. Population informatics applies data science to social genome data to answer fundamental questions about human society and population health much like bioinformatics applies data science to human genome data to answer questions about individual health. It is an emerging research area at the intersection of SBEH (Social, Behavioral, Economic, & Health) sciences, computer science, and statistics in which quantitative methods and computational tools are used to answer fundamental questions about our society. [[File:Data science.png|alt=Data Science|thumb|Data Science]

Introduction

History

The term was first used in August 2012 when the Population Informatics Lab was founded at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by Dr. Hye-Cung Kum. The term was first defined in a peer reviewed article in 2013[1] and further elaborated on in another article in 2014.[2] The first Workshop on Population Informatics for Big Data was held at the ACM SIGKDD conference in Sydney, Australia, in August 2015.

Goals

To study social, behavioral, economic, and health sciences using the massive data collections, aka social genome data, about people. The primary goal of population informatics is to increase the understanding of social processes by developing and applying computationally intensive techniques to the social genome data.

Some of the important sub-disciplines are :

- Business analytics

- Social computing: social network data analysis

- Policy informatics

- Public health informatics

- Computational journalism

- Computational transportation science

- Computational epidemiology

- Computational economics

- Computational sociology

- Computational social science

Approaches

Record Linkage, the task of finding records in a dataset that refer to the same entity across different data sources, is a major activity in the population informatics field because most of the digital traces about people are fragmented in many heterogeneous databases that need to be linked before analysis can be done.

Once relevant datasets are linked, the next task is usually to develop valid meaningful measures to answer the research question. Often developing measures involves iterating between inductive and deductive approaches with the data and research question until usable measures are developed because the data were collected for other purposes with no intended use to answer the question at hand. Developing meaningful and useful measures from existing data is a major challenge in many research projects. In computation fields, these measures are often called features.

Finally, with the datasets linked and required measures developed, the analytic dataset is ready for analysis. Common analysis methods include traditional hypothesis driven research as well more inductive approaches such as data science and predictive analytics.

Relation to other fields

Computational social science refers to the academic sub-disciplines concerned with computational approaches to the social sciences. This means that computers are used to model, simulate, and analyze social phenomena. Fields include computational economics and computational sociology. The seminal article on computational social science is by Lazer et al. 2009[3] which was a summary of a workshop held at Harvard with the same title. However, the article does not define the term computational social science precisely.

In general, computational social science is a broader field and encompasses population informatics. Besides population informatics, it also includes complex simulations of social phenomena. Often complex simulation models use results from population informatics to configure with real world parameters.

Data Science for Social Good (DSSG) is another similar field coming about. But again, DSSG is a bigger field applying data science to any social problem that includes study of human populations but also many problems that do not use any data about people.

Population reconstruction is the multi-disciplinary field to reconstruct specific (historical) populations by linking data from diverse sources, leading to rich novel resources for study by social scientists.[4]

Related groups and workshops

The firstWorkshop on Population Informatics for Big Data was held at the ACM SIGKDD conference in Sydney, Australia, in 2015. The workshop brought together computer science researchers, as well as public health practitioners and researchers. This Wikipedia page started at the workshop.

The International Population Data Linkage Network (IPDLN) facilitates communication between centres that specialize in data linkage and users of the linked data. The producers and users alike are committed to the systematic application of data linkage to produce community benefit in the population and health-related domains.

Challenges

Three major challenges specific to population informatics are:

- Preserving privacy of the subjects of the data – due to increasing concerns of privacy and confidentiality sharing or exchanging sensitive data about the subjects across different organizations is often not allowed. Therefore, population informatics need to be applied on encrypted data or in a privacy-preserving setting.[1][5][6]

- The need for error bounds on the results – since real world data often contain errors and variations error bound need to be used (for approximate matching) so that real decisions that have direct impact on people can be made based on these results.[7][8] Research on error propagation in the full data pipeline from data integration to final analysis is also important.[9]

- Scalability – databases are continuously growing in size which makes population informatics computationally expensive in terms of the size and number of data sources.[10] Scalable algorithms need to be developed for providing efficient and practical population informatics applications in the real world context.

See also

References

- Kum, Hye-Chung; Ahalt, Stanley (2013-01-01). "Privacy-by-Design: Understanding Data Access Models for Secondary Data". AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science Proceedings AMIA Summit on Translational Science. 2013: 126–130. ISSN 2153-4063. PMC 3845756. PMID 24303251.

- Kum, Hye-Chung; Krishnamurthy, A.; Machanavajjhala, A.; Ahalt, S.C. (2014-01-01). "Social Genome: Putting Big Data to Work for Population Informatics". Computer. 47 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1109/MC.2013.405. ISSN 0018-9162. S2CID 6275413.

- Lazer, David; Pentland, Alex (Sandy); Adamic, Lada; Aral, Sinan; Barabasi, Albert Laszlo; Brewer, Devon; Christakis, Nicholas; Contractor, Noshir; Fowler, James (2009-02-06). "Life in the network: the coming age of computational social science". Science. 323 (5915): 721–723. doi:10.1126/science.1167742. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 2745217. PMID 19197046.

- Bloothooft, G.; Christen, P.; Mandemakers, K.; Schraagen, M. (2015). Population Reconstruction - Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-19884-2. ISBN 978-3-319-19883-5.

- Dinusha Vatsalan, Peter Christen, and Vassilios S. Verykios. "A taxonomy of privacy-preserving record linkage techniques." Journal of Information Systems (Elsevier), 38(6): 946-969, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.is.2012.11.005

- Kum, Hye-Chung; Krishnamurthy, Ashok; Machanavajjhala, Ashwin; Reiter, Michael K; Ahalt, Stanley (2014-03-01). "Privacy preserving interactive record linkage (PPIRL)". Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 21 (2): 212–220. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002165. ISSN 1067-5027. PMC 3932473. PMID 24201028.

- Peter Christen. "Data Matching - Concepts and Techniques for Record Linkage, Entity Resolution, and Duplicate Detection". Data-Centric Systems and Applications (Springer) 2012. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-31164-2

- Peter Christen, Dinusha Vatsalan, and Zhichun Fu. "Advanced Record Linkage Methods and Privacy Aspects for Population Reconstruction - A Survey and Case Studies". Population Reconstruction: 87-110 (Springer) 2015. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-19884-2_5

- Lahiri, P.; Larsen, Michael D. (2005-03-01). "Regression Analysis with Linked Data". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 100 (469): 222–230. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.143.1706. doi:10.1198/016214504000001277. JSTOR 27590532. S2CID 15873588.

- Thilina Ranbaduge, Dinusha Vatsalan, and Peter Christen. "Clustering-Based Scalable Indexing for Multi-party Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage". PAKDD: 549-561 (Springer) 2015 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18032-8_43