Pinguicula

Pinguicula, commonly known as butterworts, is a genus of carnivorous flowering plants in the family Lentibulariaceae. They use sticky, glandular leaves to lure, trap, and digest insects in order to supplement the poor mineral nutrition they obtain from the environment. Of the roughly 80 currently known species, 13 are native to Europe, 9 to North America, and some to northern Asia. The largest number of species is in South and Central America.

| Pinguicula | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pinguicula moranensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Lentibulariaceae |

| Genus: | Pinguicula L. |

| Species | |

|

About 80, see separate list. | |

Etymology

The name Pinguicula is derived from a term coined by Conrad Gesner, who in his 1561 work entitled Horti Germaniae commented on the glistening leaves: "propter pinguia et tenera folia…" (Latin pinguis, "fat"). The common name "butterwort" reflects this characteristic.[1]

Characteristics

The majority of Pinguicula are perennial plants. The only known annuals are P. sharpii, P. takakii, P. crenatiloba, and P. pumila. All species form stemless rosettes.

Habitat

Butterworts can be divided roughly into two main groups based on the climate in which they grow; each group is then further subdivided based on morphological characteristics. Although these groups are not cladistically supported by genetic studies,[2] these groupings are nonetheless convenient for horticultural purposes.

Tropical butterworts either form somewhat compact winter rosettes composed of fleshy leaves or retain carnivorous leaves year-round.[3] They are typically located in regions where water is least seasonally plentiful, as too damp soil conditions can lead to rotting. They are found in areas in which nitrogenous resources are known to be in low levels, infrequent or unavailable, due to acidic soil conditions.

Temperate species often form tight buds (called hibernacula) composed of scale-like leaves during a winter dormancy period. During this time the roots (with the exception of P. alpina) and carnivorous leaves wither.[4] Temperate species flower when they form their summer rosettes while tropical species flower at each rosette change.

Many butterworts cycle between rosettes composed of carnivorous and non-carnivorous leaves as the seasons change, so these two ecological groupings can be further divided according to their ability to produce different leaves during their growing season. If the growth in the summer is different in size or shape to that in the early spring (for temperate species) or in the winter (tropical species), then plants are considered heterophyllous; whereas uniform growth identifies a homophyllous species.

This results in four groupings:

- Tropical butterworts: species which do not undergo a winter dormancy but continue to alternately bloom and form rosettes.

- Heterophyllous tropical species: species that alternate between rosettes of carnivorous leaves during the warm season and compact rosettes of fleshy non-carnivorous leaves during the cool season. Examples include P. moranensis, P. gypsicola, and P. laxifolia.

- Homophyllous tropical species: these species produce rosettes of carnivorous leaves of roughly uniform size throughout the year, such as P. gigantea.

- Temperate butterworts: these plants are native to climate zones with cold winters. They produce a winter-resting bud (hibernaculum) during the winter.

- Heterophyllous temperate species: species where the vegetative and generative rosettes differ in shape and/or size, as seen in P. lutea and P. lusitanica.

- Homophyllous temperate species: the vegetative and generative rosettes appear identical, as exhibited by P. alpina, P. grandiflora, and P. vulgaris.

Roots

The root system of Pinguicula species is relatively undeveloped. The thin, white roots serve mainly as an anchor for the plant and to absorb moisture (nutrients are absorbed through carnivory). In temperate species these roots wither (except in P. alpina) when the hibernaculum is formed. In the few epiphytic species (such as P. lignicola), the roots form anchoring suction cups.

Leaves and carnivory

The leaf blade of a butterwort is smooth, rigid, and succulent, usually bright green or pinkish in colour. Depending on species, the leaves are between 2 and 30 cm (1-12") long. The leaf shape depends on the species, but is usually roughly obovate, spatulate, or linear.[5] They can also appear yellow in color with a soft feel and a greasy consistency to the leaves.

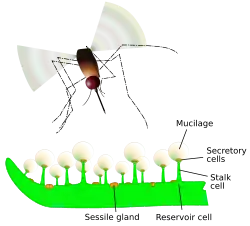

Like all members of the family Lentibulariaceae, butterworts are carnivorous.[6] The mechanistic actions that these plants use to lure and capture prey is through a means of sticky or adhesives substances that are produced by mucilage secreted by glands located on the leaf's surface. In order to catch and digest insects, the leaf of a butterwort uses two specialized glands which are scattered across the leaf surface (usually only on the upper surface, with the exception of P. gigantea and P. longifolia ssp. longifolia).[4]

One is termed a peduncular gland, and consists of a few secretory cells on top of a single stalk cell. These cells produce a mucilaginous secretion which forms visible droplets across the leaf surface. This wet appearance probably helps lure prey in search of water (a similar phenomenon is observed in the sundews). The droplets secrete limited amounts of digestive enzymes, and serve mainly to entrap insects. On contact with an insect, the peduncular glands release additional mucilage from special reservoir cells located at the base of their stalks.[4] The insect will begin to struggle, triggering more glands and encasing itself in mucilage. Some species can bend their leaf edges slightly by thigmotropism, bringing additional glands into contact with the trapped insect.[4]

The second type of gland found on butterwort leaves are sessile glands which lie flat on the leaf surface. Once the prey is entrapped by the peduncular glands and digestion begins, the initial flow of nitrogen triggers enzyme release by the sessile glands.[4] These enzymes, which include amylase, esterase, phosphatase, protease, and ribonuclease break down the digestible components of the insect body. These fluids are then absorbed back into the leaf surface through cuticular holes, leaving only the chitin exoskeleton of the larger insects on the leaf surface.

The holes in the cuticle which allow for this digestive mechanism also pose a challenge for the plant, since they serve as breaks in the cuticle (waxy layer) that protects the plant from desiccation. As a result, most butterworts live in humid environments.

_-_Keila.jpg.webp)

Butterworts are usually only able to trap small insects and those with large wing surfaces. They can also digest pollen which lands on their leaf surface. The secretory system can only function a single time, so that a particular area of the leaf surface can only be used to digest insects once.[4]

Unlike many other carnivorous plant species, butterworts do not appear to use jasmonates as a control system to switch on the production of digestive enzymes. Jasmonates are involved in the butterwort's defense against attacking insects, but not in its response to prey.[7][8][9] Of the eight enzymes identified in the digestive secretions of butterworts, alpha-amylase appears to be unique when compared to other carnivorous plants. This research suggests that butterwort may have co-opted a different set of genes in its development of carnivory.[9]

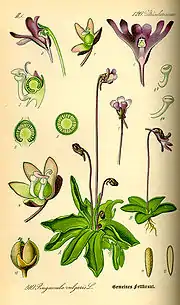

Flowers

As with almost all carnivorous plants, the flowers of butterworts are held far above the rest of the plant by a long stalk, in order to reduce the probability of trapping potential pollinators. The single, long-lasting flowers are zygomorphic, with two lower lip petals characteristic of the bladderwort family, and a spur extending from the back of the flower. The calyx has five sepals, and the petals are arranged in a two-part lower lip and a three-part upper lip. Most butterwort flowers are blue, violet or white, often suffused with a yellow, greenish or reddish tint. P. laueana and the newly described P. caryophyllacea are unique in having a strikingly red flowers. Butterworts are often cultivated and hybridized primarily for their flowers.

The shape and colors of butterwort flowers are distinguishing characteristics which are used to divide the genus into subgenera and to distinguish individual species from one another.

Fruit and seed

The round to egg-shaped seed capsules open when dry into two halves, exposing numerous small (0.5–1 mm), brown seeds. If moisture is present the silique closes, protecting the seed and opening again upon dryness to allow for wind dispersal. Many species have a net-like pattern on their seed surface to allow them to land on water surfaces without sinking, since many non-epiphytic butterworts grow near water sources. The haploid chromosome number of butterworts is either n = 8 or n = 11 (or a multiple thereof), depending on species. The exception is P. lusitanica, whose chromosome count is n = 6.

Diet

The diet will range depending on the taxonomy and size of the prey due to the plant's retention ability. These size limitations are known to be the main element influencing what prey sources this carnivorous plant can access.[10] They can also acquire nourishment from pollen and other plant parts that are high in protein, as other plants can become trapped on their leaves, thus, butterworts are both carnivorous and herbivorous plants.[6] The diet consists of several species from the arthropod taxa, majority of their prey are insects that have wings and are able to fly. The luring, retaining, and seizing of prey is the first steps in the feeding procedure for carnivorous plants; the result of the process is absorption and digestion of nutrients sourced from these food supplies. Pinguicula species do not select their prey, as they passively accumulate them through methods of sticky, adhesive leaves. However, they do have the ability of visual attraction of their colorful leaves, which will increase the likelihood of luring and capturing a specific taxa.[11] Pinguicula capture their food source/ prey by means of the mucilaginous, sticky substances produced by their stalk glands on the top of their leaf. Once the prey has become trapped in the peduncular glands, the sessile glands present will then produce enzymes needed to accomplish digestion and breaking down the digestible regions of the prey for their nutrients; taking in the fluids of the food source by means of cuticular holes present on the leaf's surface.

Vegetative propagation

As well as sexual reproduction by seed, many butterworts can reproduce asexually by vegetative reproduction. Many members of the genus form offshoots during or shortly after flowering (e.g., P. vulgaris), which grow into new genetically identical adults. A few other species form new offshoots using stolons (e.g., P. calyptrata, P. vallisneriifolia) while others form plantlets at the leaf margins (e.g., P. heterophylla, P. primuliflora).

Distribution

Butterworts are distributed throughout the northern hemisphere (map). The greatest concentration of species, however, is in humid mountainous regions of Mexico, Central America and South America, where populations can be found as far south as Tierra del Fuego. Australia and Antarctica are the only continents without any native butterworts.

Butterworts probably originated in Central America, as this is the center of Pinguicula diversity – roughly 50% of butterwort species are found here.

The great majority of individual Pinguicula species have a very limited distribution. The two butterwort species with the widest distribution - P. alpina and P. vulgaris - are found throughout much of Europe and North America. Other species found in North America include P. caerulea, P. ionantha, P. lutea, P. macroceras, P. planifolia, P. primuliflora, P. pumila, and P. villosa.

Habitat

In general, butterworts grow in nutrient-poor, alkaline soils. Some species have adapted to other soil types, such as acidic peat bogs (ex. P. vulgaris, P. calyptrata, P. lusitanica), soils composed of pure gypsum (P. gypsicola and other Mexican species), or even vertical rock walls (P. ramosa, P. vallisneriifolia, and most of the Mexican species). A few species are epiphytes (P. casabitoana, P. hemiepiphytica, P. lignicola). Many of the Mexican species commonly grow on mossy banks, rock, and roadsides in oak-pine forests. Pinguicula macroceras ssp. nortensis has even been observed growing on hanging dead grasses. P. lutea grows in pine flatwoods.[12] Other species, such as P. vulgaris, grow in fens. Each of these environments is nutrient-poor, allowing butterworts to escape competition from other canopy-forming species, particularly grasses and sedges.[13]

Butterworts need habitats that are almost constantly moist or wet, at least during their carnivorous growth stage. Many Mexican species lose their carnivorous leaves, and sprout succulent leaves, or die back to onion-like "bulbs" to survive the winter drought, at which point they can survive in bone-dry conditions. The moisture they need for growing can be supplied by either a high groundwater table, or by high humidity or high precipitation. Unlike many other carnivorous plants that require sunny locations, many butterworts thrive in part-sun or even shady conditions.

Conservation status

The environmental threats faced by various Pinguicula species depend on their location and on how widespread their distribution is. Most endangered are the species which are endemic to small areas, such as P. ramosa, P. casabitoana, and P. fiorii. These populations are threatened primarily by habitat destruction. Wetland destruction has threatened several US species. Most of these are federally listed as either threatened or endangered, and P. ionantha is listed on CITES appendix I, giving it additional protection.

Botanical history

The first mention of butterworts in botanical literature is an entry entitled Zitroch chrawt oder schmalz chrawt ("lard herb") by Vitus Auslasser in his 1479 work on medicinal herbs entitled Macer de Herbarium. The name Zittrochkraut is still used for butterworts in Tirol, Austria.

In 1583, Clusius already distinguished between two forms in his Historia stirpium rariorum per Pannoniam, Austriam: a blue-flowered form (P. vulgaris) and a white-flowered form (Pinguicula alpina). Linnaeus added P. villosa and P. lusitanica when he published his Species Plantarum in 1753. The number of known species rose sharply with the exploration of the new continents in the 19th century; by 1844, 32 species were known.

It was only in the late 19th century that the carnivory of this genus began to be studied in detail. In a letter to Asa Gray dated June 3, 1874, Charles Darwin mentioned his early observations of the butterwort's digestive process and insectivorous nature.[14] Darwin studied these plants extensively.[15] S. J. Casper's large 1966 monograph of the genus[16] included 46 species, a number which has almost doubled since then. Many exciting discoveries have been made in recent years, especially in Mexico. Another important development in the history of butterworts is the formation of the International Pinguicula Study Group, an organization dedicated to furthering the knowledge of this genus and promoting its popularity in cultivation, in the 1990s.

Uses

Butterworts are widely cultivated by carnivorous plant enthusiasts. The temperate species and many of the Mexican butterworts are relatively easy to grow and have therefore gained relative popularity. Two of the most widely grown plants are the hybrid cultivars Pinguicula × 'Sethos' and Pinguicula × 'Weser'. Both are crosses of Pinguicula ehlersiae and Pinguicula moranensis, and are employed by commercial orchid nurseries to combat pests.

Butterworts also produce a strong bactericide which prevents insects from rotting while they are being digested. According to Linnaeus, this property has long been known by northern Europeans, who applied butterwort leaves to the sores of cattle to promote healing.[17] Additionally, butterwort leaves were used to curdle milk and form a buttermilk-like fermented milk product called filmjölk (Sweden) and tjukkmjølk (Norway).[18]

Classification

Pinguicula belong to the bladderwort family (Lentibulariaceae), along with Utricularia and Genlisea. Siegfried Jost Casper systematically divided them into three subgenera with 15 sections.[16]

A detailed study of the phylogenetics of butterworts by Cieslak et al. (2005)[2] found that all of the currently accepted subgenera and many of the sections were polyphyletic. The diagram below gives a more accurate representation of the correct cladogram. Polyphyletic sections are marked with an *.

┌────Clade I (Sections Temnoceras *, Orcheosanthus *, Longitubus, │ Heterophyllum *, Agnata *, Isoloba *, Crassifolia) │ ┌───┤ │ │ │ │ ┌──────┤ └────Clade II (Section Micranthus * = P. alpina) │ │ │ │ ┌───┤ └────────Clade III (Sections Micranthus *, Nana) │ │ │ │ ───┤ └───────────────Clade IV (Section Pinguicula) │ │ └───────────────────Clade V (Sections Isoloba *, Ampullipalatum, Cardiophyllum)

References

Much of the content of this article comes from the equivalent German-language Wikipedia article (retrieved March 29, 2009).

- "How to Grow Your Indoor Butterworts (Pinguicula)". UKHouseplants. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Cieslak T, Polepalli JS, White A, Müller K, Borsch T, Barthlott W, Steiger J, Marchant A, Legendre L (2005). "Phylogenetic analysis of Pinguicula (Lentibulariaceae): chloroplast DNA sequences and morphology support several geographically distinct radiations". American Journal of Botany. 92 (10): 1723–1736. doi:10.3732/ajb.92.10.1723. PMID 21646090.

- "Carnivorous plant | botany". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- Legendre L (2002). "The genus Pinguicula L. (Lentibulariaceae): an overview". Acta Botanica Gallica. 141 (1): 77–95.

- "Carnivorous Butterwort Care – How To Grow Butterworts". Gardening Know How. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- Zamora, R. (1990). "The feeding ecology of a carnivorous plant (Pinguicula nevadense): Prey analysis and capture constraints". Oecologia. 84 (3): 376–379. doi:10.1007/bf00329762. PMID 28313028. S2CID 8038140.

- Pain, Stephanie (2 March 2022). "How plants turned predator". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-030122-1. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Hedrich, Rainer; Fukushima, Kenji (17 June 2021). "On the Origin of Carnivory: Molecular Physiology and Evolution of Plants on an Animal Diet". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 72 (1): 133–153. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-080620-010429. ISSN 1543-5008. PMID 33434053. S2CID 231595236. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Kocáb, Ondřej; Jakšová, Jana; Novák, Ondřej; Petřík, Ivan; Lenobel, René; Chamrád, Ivo; Pavlovič, Andrej (22 June 2020). "Jasmonate-independent regulation of digestive enzyme activity in the carnivorous butterwort Pinguicula × Tina". Journal of Experimental Botany. 71 (12): 3749–3758. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa159. PMC 7307851. PMID 32219314. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Zamora, Regino (1990). "The Feeding Ecology of a Carnivorous Plant (Pinguicula nevadense): Prey Analysis and Capture Constraints". Oecologia. 84 (3): 376–379. Bibcode:1990Oecol..84..376Z. doi:10.1007/BF00329762. ISSN 0029-8549. JSTOR 4219437. PMID 28313028. S2CID 8038140.

- "All About the Butterworts Plant". www.carnivorous--plants.com. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- Keddy PA, Smith L, Campbell DR, Clark M, Montz G (2006). "Patterns of herbaceous plant diversity in southeastern Louisiana pine savannas". Applied Vegetation Science. 9: 17–26. doi:10.1111/j.1654-109X.2006.tb00652.x.

- Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. Chapter 5.

- Darwin, Charles (2015). The Correspondence of Charles Darwin: Volume 22, 1874. Cambridge University Press. p. 487. ISBN 978-1-316-24095-3.

- Darwin C (1875). Insectivorous plants. London: John Murray. ISBN 1-4102-0174-0. Archived from the original on 2006-09-23.

- Casper SJ (1966). Monographie der Gattung Pinguicula L. (Heft 127/128, Vol 31). Stuttgart: Bibliotheca Botanica.

- D'Amato P (1988). The Savage Garden: Cultivating Carnivorous Plants. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-89815-915-6.

- Amilien, Virginie; Torjusen, Hanne; Vittersø, Gunnar (2005). "From local food to terroir product ? - Some views about Tjukkmjølk, the traditional thick sour milk from Røros, Norway". Anthropology of Food (4). doi:10.4000/aof.211.

Further reading

- Barthlott W, Porembski S, Seine R, Theisen I (2004). Karnivoren. Stuttgart: Verlag Eugen Ulmer. ISBN 3-8001-4144-2.

- Müller K, Borsch T, Legendre L, Porembski S, Theisen I, Barthlott W (2004). "Evolution of carnivory in Lamiales". Plant Biology. 6 (4): 1–14. doi:10.1055/s-2004-817909. PMID 15248131.

- Keddy, P.A. (2010). Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Givnish, T. J. (1988). Ecology and evolution of carnivorous plants. In Plant–Animal Interactions, ed. W. B. Abrahamson, pp. 243–90. New York: McGraw-Hill.

External links

Media related to Pinguicula at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pinguicula at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Pinguicula at Wikispecies

Data related to Pinguicula at Wikispecies- An exhaustive website on the genus Pinguicula

- Schlauer, J. Carnivorous Plant Database, version 15 November 16: 25.

- Flora Europaea: Pinguicula species list

- Botanical Society of America, Pinguicula - the Butterworts