Art in Medieval Scotland

Art in Medieval Scotland includes all forms of artistic production within the modern borders of Scotland, between the fifth century and the adoption of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. In the early Middle Ages, there were distinct material cultures evident in the different federations and kingdoms within what is now Scotland. Pictish art was the only uniquely Scottish Medieval style; it can be seen in the extensive survival of carved stones, particularly in the north and east of the country, which hold a variety of recurring images and patterns. It can also be seen in elaborate metal work that largely survives in buried hoards. Irish-Scots art from the kingdom of Dál Riata suggests that it was one of the places, as a crossroads between cultures, where the Insular style developed.

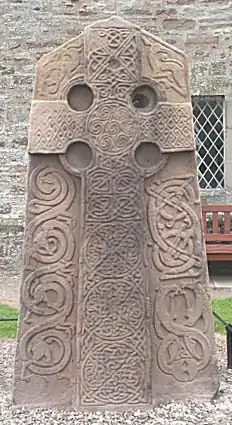

Insular art is the name given to the common style that developed in Britain and Ireland from the eighth century and which became highly influential in continental Europe and contributed to the development of Romanesque and Gothic styles. It can be seen in elaborate jewellery, often making extensive use of semi-precious stones, in the heavily carved high crosses found particularly in the Highlands and Islands, but distributed across the country and particularly in the highly decorated illustrated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells, which may have been begun, or wholly created at the monastic centre of Iona.

Scotland adopted the Romanesque style relatively late and retained and revived elements of its style after the Gothic style had become dominant from the thirteenth century. Much of the best Scottish artwork of the High and Late Middle Ages was either religious in nature or realised in metal and woodwork, and has not survived the impact of time and the Reformation. However, examples of sculpture are extant as part of church architecture, including evidence of elaborate church interiors. From the thirteenth century there are relatively large numbers of monumental effigies. Native craftsmanship can be seen in a variety of items. Visual illustration can be seen in the illumination of charters and occasional survivals of church paintings. Surviving copies of individual portraits are relatively crude, but more impressive are the works or artists commissioned from the continent, particularly the Netherlands.

Early Middle Ages

Pictish stones

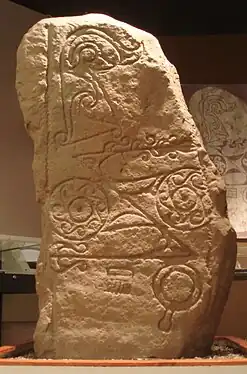

About 250 Pictish stones survive and have been assigned by scholars to three classes.[1] Class I stones are those thought to date to the period up to the seventh century and are the most numerous group. The stones are largely unshaped and include incised symbols of animals such as fish and the Pictish beast, everyday objects such as mirrors, combs and tuning forks and abstract symbols defined by names including V-rod, double disc and Z-rod. They are found between from the Firth of Forth to Shetland. The greatest concentrations are in Sutherland, around modern Inverness and Aberdeen. Good examples include the Dunrobin (Sutherland) and Aberlemno stones (Angus).[2]

Class II stones are carefully shaped slabs dating after the arrival of Christianity in the eighth and ninth centuries, with a cross on one face and a wide range of symbols on the reverse. In smaller numbers than Class I stones, they predominate in southern Pictland, in Perth, Angus and Fife. Good examples include Glamis 2, which contains a finely executed Celtic cross on the main face with two opposing male figures, a centaur, cauldron, deer head and a triple disc symbol and Cossans, Angus, which shows a high-prowed Pictish boat with oarsmen and a figure facing forward in the prow.[2] Class III stones are thought to overlap chronologically with Class II stones.[2] Most are elaborately shaped and incised cross-slabs, some with figurative scenes, but lacking idiomatic Pictish symbols. They are widely distributed but predominate in the southern Pictish areas.[2]

Pictish metalwork

Items of metalwork have been found throughout Pictland. The earlier Picts appear to have had a considerable amount of silver available, probably from raiding further south, or the payment of subsidies to keep them from doing so. The very large hoard of late Roman hacksilver found at Traprain Law may have originated in either way. The largest hoard of early Pictish metalwork was found in 1819 at Norrie's Law in Fife, but unfortunately much was dispersed and melted down.[3] Over ten heavy silver chains, some over 0.5 metres (1.6 ft) long, have been found from this period; the double-linked Whitecleuch Chain is one of only two that have a penannular ring, with symbol decoration including enamel, which shows how these were probably used as "choker" necklaces.[3] The St Ninian's Isle Treasure of 28 silver and silver-gilt objects, contains perhaps the best collection of late Pictish forms, from the Christian period, when Pictish metalwork style, as with stone-carving, gradually merged with Insular, Anglo-Saxon and Viking styles.[4]

Irish-Scots art

Thomas Charles-Edwards has suggested that the kingdom of Dál Riata was a cross-roads between the artistic styles of the Picts and those of Ireland, with which the Scots settlers in what is now Argyll kept close contacts. This can be seen in representations found in excavations of the fortress of Dunadd, which combine Pictish and Irish elements.[5] This included extensive evidence for the production of high status jewellery and moulds from the seventh century that indicate the production of pieces similar to the Hunterston brooch, found in Ayrshire, which may have been made in Dál Riata, but with elements that suggest Irish origins. These and other finds, including a trumpet spiral decorated hanging bowl disc and a stamped animal decoration (or pressblech), perhaps from a bucket or drinking horn, indicate the ways in which Dál Riata was one of the locations where the Insular style was developed.[6] In the eighth and ninth centuries the Pictish elite adopted true penannular brooches with lobed terminals from Ireland. Some older Irish pseudo-penannular brooches were adapted to the Pictish style, for example the Breadalbane Brooch (British Museum). The eighth century Monymusk Reliquary has elements of Pictish and Irish style.[7]

Early Anglo-Saxon art

Early examples of Anglo-Saxon art are largely metalwork, particularly bracelets, clasps and jewellery, that has survived in pagan burials and in exceptional items such as the intricately carved whalebone Franks Casket, thought to have been produced in Northumbria in the early eighth century, which combines pagan, classical and Christian motifs.[8] There is only one known pagan burial in Scotland, at Dalmeny Midlothian, which contains a necklace of beads similar to those found in mid-seventh-century southern England. Other isolated finds include a gold object from Dalmeny, shaped like a truncated pyramid, with filigree and garnet, similar to sword harness mounts found at Sutton Hoo. There is also a bun-shaped loom from Yetholm, Roxburghshire and a ring with an Anglian runic inscription. From eastern Scotland there is a seventh-century sword pommel from Culbin Sands, Moray and the Burghead drinking horn mount.[9] After Christianisation in the seventh century artistic styles in Northumbria, which then reached to the Firth of Forth, interacted with those in Ireland and what is now Scotland to become part of the common style historians have identified as Insular or Hiberno-Saxon.[10]

Insular art

Insular art, or Hiberno-Saxon art, is the name given to the common style produced in Scotland, Britain and Anglo-Saxon England from the seventh century, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon forms.[11] Surviving examples of Insular art are found in metalwork, carving, but mainly in illuminated manuscripts. In manuscripts surfaces are highly decorated with intricate patterning, with no attempt to give an impression of depth, volume or recession. The best examples include the Book of Kells, which may have been wholly or partly created in Iona, and the Book of Durrow, which may be from Ireland or Northumbria. Carpet pages are a characteristic feature of Insular manuscripts, although historiated initials (an Insular invention), canon tables and figurative miniatures, especially Evangelist portraits, are also common. The finest era of the style was brought to an end by the disruption to monastic centres and aristocratic life of the Viking raids in the late eighth century.[12]

Christianity discouraged the burial of grave goods so the majority of examples of insular metalwork that survive from the Christian period have been found in archaeological contexts that suggest they were rapidly hidden, lost or abandoned.[13] There are a few exceptions, notably portable shrines ("cumdachs") for books or relics, several of which have been continuously owned, mostly by churches on the Continent—though the Monymusk Reliquary has always been in Scotland.[14] The highest quality survivals are either secular jewellery, the largest and most elaborate pieces probably for male wearers, tableware or altarware. The finest church pieces were probably made by secular workshops, often attached to a royal household, though other pieces were made by monastic workshops.[15] There are a number of large brooches, each of their designs is wholly individual in detail, and the workmanship is varied. Many elements of the designs can be directly related to elements used in manuscripts. Surviving stones used in decoration are semi-precious ones, with amber and rock crystal among the commonest, and some garnets. Coloured glass, enamel and millefiori glass, probably imported, are also used.[16] None of the major insular manuscripts, like the Book of Kells, have preserved their elaborate jewelled metal covers, but documentary evidence indicates that these were as spectacular as the few remaining continental examples.[17]

The most significant survivals in sculpture are in High crosses, large free-standing stone crosses, usually carved in relief with patterns, biblical iconography and occasionally inscriptions. The tradition may have begun in Ireland or Anglo-Saxon England and then spread to Scotland.[18] They are found throughout the British Isles and often feature a stone ring around the intersection, forming a Celtic cross, apparently an innovation of Celtic Christianity, that may have begun at Iona.[19] Distribution in Scotland is heaviest in the Highlands and Islands and they can be dated to the period c. 750 to 1150.[18] All the surviving crosses are of stone, but there are indications that large numbers of wooden crosses may also have existed. In Scotland biblical iconography is less common than in Ireland, but the subject of King David is relatively frequently depicted. In the east the influence of Pictish sculpture can be seen, in areas of Viking occupation and settlement, crosses for the tenth to the twelfth centuries have distinctive Scandinavian patterns, often mixed with native styles. Important examples dated to the eighth century include St Martin's Cross on Iona, the Kildalton Cross from the Hebrides and the Anglo-Saxon Ruthwell Cross.[18] Through the Hiberno-Scottish mission to the continent, insular art was highly influential on subsequent European Medieval art, especially the decorative elements of Romanesque and Gothic styles.[20]

Viking age art

Viking art avoided naturalism, favouring stylised animal motifs to create its ornamental patterns. Ribbon-interlace was important and plant motifs became fashionable in the tenth and eleventh centuries.[21] Most Scottish artefacts come from 130 "pagan" burials in the north and west from the mid-ninth to the mid-tenth centuries.[22] These include jewellery, weapons and occasional elaborate high status items.[23] Amongst the most impressive of these is the Scar boat burial, on Orkney, which contained an elaborate sword, quiver with arrows, a brooch, bone comb, gaming pieces and the Scar Dragon Plaque, made from whalebone, most of which were probably made in Scandinavia.[24] From the west, another boat burial at Kiloron Bay in Colonsay revealed a sword, shield, iron cauldron and enamelled scales, which may be Celtic in origin.[25] A combination of Viking and Celtic styles can be seen in a penannular brooch from Pierowall in Orkney, which has a Pictish-style looped pin. It is about two inches in diameter, with traces of gilding, and probably housed a piece of amber surrounded by interweaving ribbons.[26] After the conversion to Christianity, from the tenth to the twelfth centuries, stone crosses and cross-slabs in Viking occupied areas of the Highlands and Islands were carved with successive styles of Viking ornament.[27] They were frequently mixed with native interlace and animal patterns. Examples include the eleventh-century cross-slab from Dóid Mhàiri on the island of Islay, where the plant motifs on either side of the cross-shaft are based upon the Ringerike style of Viking art.[28] The most famous artistic find from modern Scotland, the Lewis Chessmen, from Uig, were probably made in Trondheim in Norway, but contain some decoration that may have been influenced by Celtic patterns.[29]

Late Middle Ages

Architecture and sculpture

Architectural evidence suggests that, while the Romanesque style peaked in much of Europe in the later eleventh and early twelfth century, it was still reaching Scotland in the second half of the twelfth century[30] and was revived in the late fifteenth century, perhaps as a reaction to the English perpendicular style that had come to dominate.[31] Much of the best Scottish artwork of the High and Late Middle Ages was either religious in nature or realised in metal and woodwork and has not survived the impact of time and the Reformation.[32] However, examples of sculpture are extant as part of church architecture, a small number of significant crafted items have also survived and, for the end of the period, there is evidence of painting, particularly the extensive commissioning of works in the Low Countries and France.[33]

The interiors of churches were often more elaborate before the Reformation, with highly decorated sacrament houses, like the ones surviving at Deskford and Kinkell.[34] The carvings at Rosslyn Chapel, created in the mid-fifteenth century, elaborately depicting the progression of the seven deadly sins, are considered some of the finest in the Gothic style.[35] Monumental effigies began to appear in churches from the thirteenth century and they were usually fully coloured and gilded. Many were founders and patrons of churches and chapels, including members of the clergy, knights and often their wives. In contrast to England, where the fashion for stone-carved monuments gave way to brass etchings, they continued to be produced until the end of the Medieval period, with the largest group dating from the fifteenth century,[36][37] including the very elaborate Douglas tombs in the town of Douglas.[34] Sometimes the best continental artists were employed, as for Robert I's elaborate tomb in Dunfermline Abbey, which was made in his lifetime by the Parisian sculptor Thomas of Chartres, but of which only fragments now survive.[32] The greatest group of surviving sculpture from this period are from the West Highlands, beginning in the fourteenth century on Iona under the patronage of the Lordship of the Isles and continuing until the Reformation. Common motifs were ships, swords, harps and Romanesque vine leaf tracery with Celtic elements.[38]

Decorative arts

Survivals from late Medieval church fittings and objects in Scotland are exceptionally rare even compared to those from comparable areas like England or Norway, probably because of the thoroughness of their destruction in the Scottish Reformation. The Scottish elite and church now participated in a culture stretching across Europe, and many objects that do survive are imported, such as Limoges enamels.[40] It is often difficult to decide the country of creation of others, as work in international styles was produced in Scotland, along with pieces retaining more distinctive local styles.

Two secular small chests with carved whalebone panels and metal fittings illustrate some aspects of the Scottish arts. The Eglington and Fife Caskets are very similar and were probably made by the same workshop around 1500, as boxes for valuables such as jewellery or documents. The overall form of the caskets follows French examples, and the locks and metal bands are decorated in Gothic style with "simple decorations of fleurons and debased egg and dart" while the whalebone panels are carved in relief with a late form of Insular interwoven strapwork characteristic of late Medieval West Scotland.[41]

Key examples of native craftsmanship on items include the Bute mazer, the earliest surviving drinking cup of its type, made of maple-wood and with elaborate silver-gilt ornamentation, dated to around 1320.[42] The Savernake Horn was probably made for the earl of Moray in the fourteenth century and looted by the English in the mid-sixteenth century.[32] A few significant reliquaries survive from West Scotland, examples of the habit of the Celtic church of treating the possessions rather than the bones of saints as relics. As in Irish examples these were partly reworked and elaborated at intervals over a long period. These are St Fillan's Crozier and its "Coigreach" or reliquary, between them with elements from each century from the eleventh to the fifteenth, the Guthrie Bell Shrine, Iona, twelfth to fifteenth century, and the Kilmichael Glassary Bell Shrine, Argyll, mid-twelfth century.[43] The Skye Chess piece is a single elaborate piece in carved walrus ivory, with two warriors carrying heraldic shields in a framework of openwork vegetation. It is thought to be Scottish, of the mid-thirteenth century, with aspects similar to both English and Norwegian pieces.[44]

One of the largest groups of surviving works of art are the seal matrices that appear to have entered Scottish usage with feudalism in the reign of David I, beginning at the royal court and among his Anglo-Norman vassals and then by about 1250 they began to spread to the Gaelicised areas of the country. They would be made compulsory for barons of the king in a statute of 1401[45] and seal matrices show very high standards of skill and artistry.[32] Examples of items that were probably the work of continental artists include the delicate hanging lamp in St. John's Kirk in Perth, the vestments and hangings in Holyrood[33] and the Medieval maces of the Universities of St Andrews and Glasgow.[32]

Illumination and painting

Manuscript illumination continued into the late Middle Ages, moving from elaborate gospels to charters, like that confirming the rights of Kelso Abbey from 1159.[46] Very little painting from Scottish churches survives. There is only one surviving Doom painting in Scotland, at Guthrie near Arbroath, which may have been painted by the same artist as the elaborate crucifixion and other paintings at Foulis Easter, eighteen miles away.[47] As in England, the monarchy may have had model portraits of royalty used for copies and reproductions, but the versions of native royal portraits that survive are generally crude by continental standards.[33] Much more impressive are the works or artists imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the Northern Renaissance.[33] The products of these connections included a fine portrait of William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen (1488–1514);[32] the images of St Catherine and St John brought to Dunkeld; Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Church in Edinburgh, commissioned by James III, and the work after which the Flemish Master of James IV of Scotland is named.[33] There are also a relatively large number of elaborate devotional books from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, usually produced in the Low Countries and France for Scottish patrons, including the prayer book commissioned by Robert Blackadder, Bishop of Glasgow, between 1484 and 1492[32] and the Flemish illustrated book of hours, known as the Hours of James IV of Scotland, given by James IV to Margaret Tudor and described as "perhaps the finest medieval manuscript to have been commissioned for Scottish use".[48]

See also

References

- J. N. G. Ritchie and A. Ritchie, Scotland, Archaeology and Early History (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 1991), ISBN 0748602917, pp. 161–5.

- J. Graham-Campbell and C. E. Batey, Vikings in Scotland: an Archaeological Survey (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0748606416, pp. 7–8.

- S. Youngs, ed., "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th–9th centuries AD (London: British Museum Press, 1989), ISBN 0714105546, pp. 26–8.

- L. R. Laing, Later Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland (London: Osprey Publishing, 1987), ISBN 0852638744, p. 37.

- T. M. Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 0521363950, pp. 331–2.

- A. Lane, "Citadel of the first Scots", British Archaeology, 62, December 2001. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- S. Youngs, ed., "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th–9th centuries AD (London: British Museum Press, 1989), ISBN 0714105546, pp. 109–113.

- C. R. Dodwell, Anglo-Saxon Art: A New Perspective (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1982), ISBN 071900926X, pp. 2–4.

- L. Laing, The Archaeology of Late Celtic Britain and Ireland C. 400–1200 AD (London: Taylor & Francis, 1975), ISBN 0416823602, p. 28.

- C. E Karkov, The Art of Anglo-Saxon England (Boydell Press, 2011), ISBN 1843836289, p. 5.

- H. Honour and J. Fleming, A World History of Art (London: Macmillan), ISBN 0333371852, pp. 244–7.

- C. R. Dodwell, The Pictorial Arts of the West, 800–1200 (Yale UP, 1993), ISBN 0300064934, pp. 85 and 90.

- C. R. Dodwell, Anglo-Saxon Art, a New Perspective (Manchester:Manchester University Press, 1982), ISBN 071900926X, p. 4.

- S. Youngs, ed., "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork (London: British Museum Press, 1989), ISBN 0714105546, pp. 134–140.

- S. Youngs, ed., "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork (London: British Museum Press, 1989), ISBN 0714105546, pp. 15–16.

- S. Youngs, ed., "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork (London: British Museum Press, 1989), ISBN 0714105546, pp. 72–115, and 170–174 and D. M. Wilson, Anglo-Saxon Art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest (Overlook Press, 1984), pp. 113–114 and 120–130.

- R. G. Calkins, Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press 1983), pp. 57–60.

- J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1851094407, pp. 915–19.

- D. M. Wilson, Anglo-Saxon Art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest (Overlook Press), 1984, p. 118.

- G. Henderson, Early Medieval Art (London: Penguin, 1972), pp. 63–71.

- J. Graham-Campbell and C. E. Batey, Vikings in Scotland: an Archaeological Survey (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0748606416, p. 34.

- M. Carver, The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300–1300 (Boydell Press, 2006), ISBN 1843831252, p. 219.

- J. Jesch, Women in the Viking Age (Boydell & Brewer, 1991), ISBN 0851153607, p. 14.

- K. Holman, The Northern [I. E. Northern] Conquest: Vikings in Britain and Ireland (Signal Books, 2007), ISBN 1904955347, p. 137.

- L. Laing, The Archaeology of Late Celtic Britain and Ireland C. 400–1200 AD (London: Taylor & Francis, 1975), ISBN 0416823602, p. 201.

- W. Nolan, L. Ronayne and M. Dunlevy, eds, Donegal: History & Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County (Geography, 1995), ISBN 0906602459, p. 96.

- J. Koch, Celtic Culture: Aberdeen Breviary-Celticism (ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1851094407. p. 918.

- J. Graham-Campbell and C. E. Batey. Vikings in Scotland: an Archaeological Survey (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0748606416, p. 90.

- M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, p. 31.

- R. N. Swanson, The Twelfth-Century Renaissance (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), ISBN 0719042569, p. 155.

- T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, p. 190.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0333567617, pp. 127–9.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 57–9.

- I. D. Whyte and K. A. Whyte, The Changing Scottish landscape, 1500–1800 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1991), ISBN 0415029929, p. 117.

- S. H. Rigby, A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), ISBN 0631217851, p. 532.

- R. Brydall, The Monumental Effigies of Scotland: From the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century (Kessinger Publishing, 1895, rpt. 2010) ISBN 1169232329.

- K. Stevenson, Chivalry and Knighthood in Scotland, 1424–1513 (Boydell Press, 2006), ISBN 1843831929, pp. 125–8.

- M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, pp. 34–5.

- V. Glenn, Romanesque and Gothic: Decorative Metalwork and Ivory Carvings in the Museum of Scotland (National Museums of Scotland, 2003), ISBN 1901663558, pp. 105–106.

- Glenn, 1–4; Chapter III on enamels

- Glenn, 147, 186–191; both now Museum of Scotland

- Glenn, 34–38, and 16th century cover, 191–192

- Glenn, 92–115, all Museum of Scotland; MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, p. 32.

- Glenn, 146–147, 178–181; now Museum of Scotland

- Glenn, 116–144; C. J. Neville, Land, Law and People in Medieval Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748639586, pp. 83–99.

- R. Brydall, Art in Scotland: its Origins and Progress (Edinburgh and London: Blackwood, 1889), p. 17.

- M. R. Apted and W. R. Robinson, "Late fifteenth century church painting from Guthrie and Foulis Easter", Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. 95 (1964), pp. 262–79.

- D. H. Caldwell, ed., Angels, Nobles and Unicorns: Art and Patronage in Medieval Scotland (Edinburgh: National Museum of Scotland, 1982), p. 84.