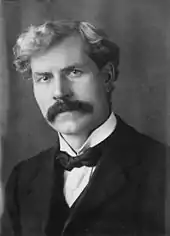

Philip Snowden, 1st Viscount Snowden

Philip Snowden, 1st Viscount Snowden, PC (/ˈsnoʊdən/; 18 July 1864 – 15 May 1937) was a British politician. A strong speaker, he became popular in trade union circles for his denunciation of capitalism as unethical and his promise of a socialist utopia. He was the first Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, a position he held in 1924 and again between 1929 and 1931. He broke with Labour policy in 1931, and was expelled from the party and excoriated as a turncoat, as the party was overwhelmingly crushed that year by the National Government coalition that Snowden supported. He was succeeded as Chancellor by Neville Chamberlain.

The Viscount Snowden | |

|---|---|

Snowden in 1923 | |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 7 June 1929 – 5 November 1931 | |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Winston Churchill |

| Succeeded by | Neville Chamberlain |

| In office 22 January 1924 – 3 November 1924 | |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Neville Chamberlain |

| Succeeded by | Winston Churchill |

| Member of Parliament for Colne Valley | |

| In office 15 November 1922 – 27 October 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Frederick Mallalieu |

| Succeeded by | Lance Mallalieu |

| Member of Parliament for Blackburn | |

| In office 8 February 1906 – 14 December 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Sir William Coddington |

| Succeeded by | Percy Dean |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 July 1864 Cowling, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 15 May 1937 (aged 72) Tilford, Surrey, England |

| Political party | Liberal (until c. 1894) Labour (c. 1894–1931) National Labour (1931–1932) None (1932–1937) |

| Spouse | |

Early life: 1864–1906

Snowden was born in Cowling in the West Riding of Yorkshire. His father John Snowden had been a weaver and a supporter of Chartism, and later a Gladstonian liberal. Snowden later wrote in his autobiography: "I was brought up in this Radical atmosphere, and it was then that I imbibed the political and social principles which I have held fundamentally ever since".[1] Although his parents and sisters were involved in weaving at the Ickornshaw Mill, he did not join them; after attending a local board school (where he received additional lessons in French and Latin from the schoolmaster) he stayed on as a pupil-teacher.[2] When he was 15 he became an insurance office clerk in Burnley.[2] During his seven years as a clerk, he studied and then passed the civil service entry examination; in 1886, he was appointed to a junior position at the Excise Office in Liverpool.[2] Snowden moved on to other posts around Scotland and then to Devon.[2]

In August 1891, when he was aged 27, Snowden severely injured his back in a cycling accident in Devon and was paralyzed from the waist down.[2] He learned to walk again with the aid of sticks within two years.[3] His Inland Revenue job was kept open for him for two years following the accident; however, owing to his condition, he decided to resign from the civil service.[2] While he was convalescing at his mother's house at Cowling he began to study socialist theory and history.[2]

Snowden joined the Liberal Party, and followed his parents in becoming a teetotaller. In 1893, in the aftermath of the formation of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in neighbouring Bradford, he was asked to give a speech for the Cowling Liberal Club on the dangers of socialism. Whilst researching the subject, Snowden instead became convinced by the ideology. He eventually joined the executive committee of the Keighley ILP in 1899, and went on to chair the ILP from 1903 to 1906. He became a prominent speaker for the party, and wrote a popular Christian socialist pamphlet with Keir Hardie in 1903, entitled The Christ that is to Be. His strident rhetoric, well-laced with statistics and evangelical themes, contrasted the evil conditions under capitalism with the moral and economic utopia of future socialism. He condemned as "bloodsuckers and parasites" local textile company executives. In 1898, he launched the Keighley Labour Journal, using it to denounce waste, pettiness, and corruption. However, he ignored the concerns of the trade unions, which he judged to be conservative and fixated on wages.[3] By 1902, he had moved his base to Leeds and toured Britain as a lecturer on politics and corruption, with his own syndicated column and short essays in numerous working class outlets. By the time he was elected Labour MP for Blackburn in 1906, he had become a well-known socialist figure, standing at the national level alongside both Keir Hardie, Professor Arnold Lupton and Ramsay MacDonald.[3][4]

Snowden married Ethel Annakin, a campaigner for women's suffrage, in 1905. He supported his wife's ideals, and he became a noted speaker at suffragist meetings and other public meetings.[3]

Member of Parliament: 1906–1924

Snowden unsuccessfully contested the Wakefield constituency in West Yorkshire in a by-election in March 1902, where he received 40 percent of the votes.[5] In 1906, he became the Labour MP for Blackburn.[6] He continued his writing and lectures, and now was advocating more radical measures than the ruling Liberal government was implementing. He even devised his own "Socialist budget" to rival David Lloyd George's 1909 "People's Budget".[3]

Snowden was in Australia on a worldwide lecture tour when the Britain entered World War I in August 1914; he did not return to Britain until February 1915. He was not a pacifist; however, he did not support recruiting for the armed forces, and he campaigned against conscription. His stance was unpopular with the public and he lost his seat in the 1918 general election. In 1922, he was elected to represent Colne Valley.[3]

Chancellor of the Exchequer: 1924

Upon Ramsay MacDonald's appointment as Prime Minister in January 1924, Snowden was appointed as the Labour Party's first ever Chancellor of the Exchequer[7] and sworn of the Privy Council.[8][9] Despite his socialist rhetoric, Snowden believed that in order to transition towards a socialist society the capitalist British economy had to recover from World War I and the Depression of 1920–1921. He therefore cut taxes and tariffs in order balance the national budget, and continued to commit the government to reentering the gold standard by 1925.[10]

In his budget, Snowden lowered the duties on tea, coffee, cocoa, chicory and sugar; reduced spending on armaments; and provided money for council housing. However, he did not implement the capital levy. Snowden claimed that because of the lowering of duties on foodstuffs consumed by the working class, the budget went "far to realize the cherished radical idea of a free breakfast table".[11] He profoundly believed in the morality of the balanced budget, with rigorous economy and not a penny wasted. He grasped how serious unemployment was becoming, but differed with the rising belief in deficit spending as a way to combat it. A. J. P. Taylor said his budget "would have delighted the heart of Gladstone".[12]

In his first budget, Snowden earmarked £38 million for the reduction of food taxes, the introduction of pensions for widows, and a reduction in the pensionable age to 65. However, only the first of these measures was realized during the first Labour Government's time in office.[13]

Opposition: 1924–1929

Although he had chaired the ILP for a second time, from 1917 to 1920, Snowden resigned from the party in 1927 because he believed it was "drifting more and more away from... evolutionary socialism into revolutionary socialism". He was also opposed to the new Keynesian economic ideas which provided a rationale for deficit spending, and criticized their expression in the Liberals' manifesto for the 1929 election, titled We can Conquer Unemployment.[3]

Chancellor of the Exchequer: 1929–1931

Snowden was again appointed Chancellor after Labour formed a government in 1929, after emerging as the largest party in the general election.[14] His economic philosophy was one of strict Gladstonian Liberalism rather than socialism. His official biographer wrote, "He was raised in an atmosphere which regarded borrowing as an evil and free trade as an essential ingredient of prosperity".[15]

He was the principal opponent to any radical economic policy to tackle the Great Depression, and blocked proposals to introduce protectionist tariffs. In 1930 he rejected the Mosley Manifesto issued by junior Labour ministers led by Oswald Mosley proposing a programme of high spending on public works and autarkic Imperial Preference to combat unemployment.[16] The government eventually collapsed over arguments about a budget deficit when Snowden accepted the Committee on National Expenditure's recommendations for budget cuts while a significant minority of ministers led by Arthur Henderson, the National Executive Committee, and the General Council of the Trades Union Congress refused to enact cuts in unemployment benefits.[17][18]

Snowden retained the position of Chancellor during the National Government of 1931. As a consequence he was expelled from the party, along with MacDonald and Jimmy Thomas. In a BBC Radio broadcast on 16 October 1931, he called Labour's policies "Bolshevism run mad" and contrasted them unfavourably with his own "sane and evolutionary Socialism".[19] Snowden decided not to stand for parliament in the election of November 1931. At that election, Labour's number of seats declined catastrophically from 288 to 52. It was during that year he had prostate gland surgery, following which his health and mobility declined.[3]

Robert Skidelsky is representative of the Keynesians who have charged that Snowden and MacDonald were blinded by their economic philosophy that required balanced budgets, sound money, the gold standard and free trade, regardless of the damage that Keynesians thought it would do to the economy and the people.[20] However, with the decline of Keynesianism as a model after 1968, historians have re-evaluated Snowden in a more favourable light. Ross McKibbin argues that the Labour government had very limited room to manoeuvre in 1929–31, and it did as well as could be expected; and that it handled the British economy better than most foreign governments handled theirs, and the Great Depression was less severe in Britain than elsewhere.[21] Future Prime Minister Harold Wilson would also be inspired by Snowden's policies to resist a devaluation of the pound sterling in 1967.[22]

Later life: 1931–1937

In the 1931 Dissolution Honours he was raised to the peerage as Viscount Snowden of Ickornshaw, in the West Riding of the County of York,[23] and served as Lord Privy Seal in the National government from 1931[24] to 1932, when he resigned in protest at the enactment of a full scheme of Imperial Preference and protectionist tariffs. That year, Snowden said there was never a greater mistake than to say that Cobdenism was dead: "Cobdenism was never more alive throughout the world than it was to-day ... To-day the ideas of Cobden were in revolt against selfish nationalism. The need for the breaking down of trade restrictions, which took various forms, was universally recognized even by those who were unable to throw off those shackles".[25]

He subsequently wrote his Autobiography in which he strongly attacked MacDonald. In the 1935 general election, Snowden supported the Keynesian economic programme proposed by Lloyd George ("Lloyd George's New Deal"), despite it being a complete repudiation of Snowden's own classical liberal fiscal policies. Snowden claimed that he was returning to long-held economic views, but that these had been "temporarily inadvisable" during the crisis of 1931, when "national necessity" demanded cutting public expenditure.[3]

Lord Snowden died of a heart attack at his home, Eden Lodge, Tilford, Surrey, on 15 May 1937, aged 72. After cremation at Woking Crematorium his ashes were scattered on Cowling Moor near Ickornshaw. His library of books and pamphlets was presented to Keighley Public Library by his widow, and a cairn was erected to his memory on Ickornshaw Moor in 1938.[3]

His viscountcy died with him. Lady Snowden died in February 1951, aged 69.

Notes

- Philip, Viscount Snowden, An Autobiography. Volume One. 1864-1919 (London: Ivor Nicholson and Watson, 1934), p. 19.

- "Lord Snowden." Times [London, England] 17 May 1937: 15. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 8 September 2013.

- Duncan Tanner, "Snowden, Philip, Viscount Snowden (1864–1937)]", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004;

- Millman, Brock, Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain, 2000, page 186.

- "Election intelligence". The Times. No. 36725. London. 26 March 1902. p. 10.

- "No. 27885". The London Gazette. 13 February 1906. p. 1038.

- "No. 32901". The London Gazette. 25 January 1924. p. 770.

- "No. 32901". The London Gazette. 25 January 1924. p. 769.

- "No. 13992". The Edinburgh Gazette. 29 January 1924. p. 147.

- Thorpe 1997, p. 59.

- Time, Labor's Budget, 12 May 1924

- Taylor, English History, 1914-1945, p. 212.

- Foundations of the Welfare State, 2nd Edition by Pat Thane, published 1996

- "No. 33508". The London Gazette. 21 June 1929. p. 4106.

- Keith Laybourn (1988). Philip Snowden: a biography : 1864-1937. Temple Smith. p. 97. ISBN 9780566070174.

- Thorpe 1997, p. 71-72.

- Thorpe 1997, p. 75-76.

- Robert Skidelsky, Politicians and the Slump: The Labour Government of 1929–1931 (1967)

- Kevin Jeffreys (1999). Leading Labour: From Keir Hardie to Tony Blair. I.B.Tauris. p. 33. ISBN 9781860644535.

- Skidelsky, Politicians and the Slump: The Labour Government of 1929-1931 (1967)

- Ross McKibbin, "The Economic Policy of the Second Labour Government 1929-1931," Past & Present (1975) #68 pp. 95-123 in JSTOR

- Thorpe 1997, p. 162.

- "No. 33775". The London Gazette. 27 November 1931. p. 7658.

- "No. 33772". The London Gazette. 17 November 1931. p. 7409.

- The Times (8 July 1932), p. 9.

Bibliography

- Cross, Colin (1966). Philip Snowden. Barrie & Jenkins.

- Laybourn, Keith; James, David (1987). Keith Laybourn; David James (eds.). Philip Snowden: The First Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer. Bradford Arts, Museums and Libraries Service.

- Laybourn, Keith (1988). Philip Snowden. A Biography, 1864–1937. Dartmouth Publishing.

- Snowden, Philip, Viscount (1934). An Autobiography. Vol. One 1864-1919. London: Ivor Nicholson and Watson.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Snowden, Philip, Viscount (1934). An Autobiography. Vol. Two 1919-1934. London: Ivor Nicholson and Watson.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tanner, Duncan (2004). "Snowden, Philip, Viscount Snowden (1864–1937)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36181. Retrieved 1 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Thorpe, Andrew (1997). A History of the British Labour Party (1 ed.). London: Red Globe Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-25305-0. ISBN 9781137409829.

- Secondary sources

- McKibbin, Ross (1975). "The Economic Policy of the Second Labour Government 1929-1931". Past & Present. #68: 95–123. doi:10.1093/past/68.1.95.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1965). English History, 1914-1945. Oxford University Press.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Philip Snowden

- Works by Philip Snowden at Faded Page (Canada)

- Philip Snowden - Blackburn Labour Party

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- Newspaper clippings about Philip Snowden, 1st Viscount Snowden in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

_(2022).svg.png.webp)