Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society

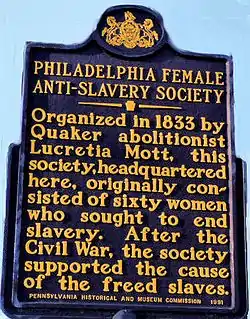

The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) was founded in December 1833 and dissolved in March 1870 following the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It was founded by eighteen women, including Mary Ann M'Clintock,[1] Margaretta Forten, her mother Charlotte, and Forten's sisters Sarah and Harriet.[2][3]

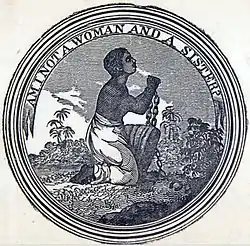

The society was a local chapter affiliated with the American Anti-Slavery Society created the same year by William Lloyd Garrison and other leading male abolitionists. The PFASS was formed as a result of the inability of women to become members of the male abolitionist organization. This predominantly white though racially mixed female abolitionist organization illustrates the important behind-the-scenes collective roles women played in the abolitionist movement. It also exemplifies the dynamics of gender and race within American patriarchal society that emphasized the cult of true womanhood (or cult of domesticity) in the nineteenth century.

Membership

Historians often cite the PFASS as one of the few racially integrated anti-slavery societies in the antebellum era, rare even among female anti-slavery societies. PFASS membership typically came from middle-class backgrounds.

The best known white female abolitionist affiliated with the PFASS is Lucretia Mott. Other white women who were mainstays of the interracial organization included Sarah Pugh and Mary Grew, respectively the president and corresponding secretary of PFASS for most of its existence.[4] Angelina Grimké, a noted female abolitionist, also joined the organization. White female members were mostly Quakers; historian Jean R. Soderlund maintains thirteen of the seventeen founding white women founders were Hicksite Quakers. Free black females helped organize the society as well. Prominent individuals included Grace Bustill Douglass and Sarah Mapps Douglass, Hetty Reckless, and Charlotte Forten (wife of notable abolitionist James Forten) and her daughters, Harriet, Sarah, and Margaretta . These women represented the city's African American elite.[5] Historian Shirley Yee states that seven of the eighteen women who signed the PFASS constitution were black, and ten black women appear regularly in society records. Furthermore, many black women members consistently served in leadership roles.[6]

Sarah Forten was a co-founder of the Society and served on its board of managers for three consecutive terms. Margaretta Forten was a co-founder of the Society and often served as recording secretary or treasurer, as well as helping to draw up its organizational charter and serving on its educational committee.[7] She also offered the Society's last resolution, which praised the post-civil war amendments as a success for the anti-slavery cause.[2] Through holding key offices, historian Janice Sumler-Lewis claims the efforts of the Forten women enabled this predominantly white organization to reflect a black abolitionist perspective that oftentimes was more militant.[8]

Historian Julie Winch suggests that the free black middle-class females in Philadelphia initially organized female literacy societies prior to their membership in the PFASS. She argues these literacy societies offered black middle-class females opportunities to educate themselves and their children as well as to develop the necessary skills for community activism. According to Winch, it was hardly coincidental that members of the literacy societies also enrolled in the PFASS, and these societies were an integral part of the antislavery crusade.[9]

Writer Evette Dionne notes that this amount of integration and cooperation in a society among black and white women would have been quite rare even in a free city like Philadelphia. Black members contributed to writing the constitution and establishing the organization's priorities.[10]

Abolitionist activities

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

In the 1830s, the PFASS largely focused on circulating antislavery petitions, holding public meetings, organizing fundraising efforts, and financially supporting community improvement for free blacks. Between 1834 and 1850, the PFASS sent numerous petitions to the Philadelphia state legislature and to Congress. The PFASS pressed the Pennsylvania legislature to allow jury trials for suspected fugitive slaves. They petitioned Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia and prohibit the interstate slave trade. Black female leaders in the PFASS served on committees that coordinated these drives. During this period when women had not yet been granted the right to vote, petition drives were one of the few forms of political expression available to women. Petition campaigns drew women out of their homes and into their neighborhoods where they conducted massive grassroots propaganda campaigns. Face-to-face communications and door-to-door efforts by women not only challenged social norms of femininity but it also "moved the antislavery movement from a predominantly moral to a predominantly political focus".[11] Petitions like these eventually caused the U.S. House of Representatives to pass the gag rule.

The refusal of Congress to consider these petitions as well as fear of mob violence led to a shift in strategies in the 1840s. As the society matured, it reduced efforts to circulate petitions and increasingly devoted time to fundraising. The primary PFASS fundraiser was an annual fair in which handcrafted items such as needlework with abolitionist inscriptions and antislavery publications were sold. For example, the well-known piece of abolitionist literature, The Anti-Slavery Alphabet was printed and sold at the 1846 Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Fair. PFASS meetings consisted of coordinating activities for the fair and organizing sewing circles. By the 1850s, the fairs became elaborate occasions. In addition to selling items, the fairs featured speeches by well known abolitionists that attracted large audiences willing to pay admissions fees.[12] The society's successful fundraising efforts enabled it to secure power and influence in the state anti-slavery society. Throughout the entire period, the PFASS provided a large proportion of all funds donated to the state society. From 1844 to 1849, funds raised by the Philadelphia women covered approximately 20 percent of the state anti-slavery society budget and accounted for 31 to 45 percent of donations. Hence, women were able to keep a high profile and assert their authority in leadership roles within the statewide abolitionist movement.[13]

Financially supporting the free black community was also an aspect of the activities within the PFASS. Led primarily by its black female membership, the PFASS financially supported Sarah Douglass's school for free black girls. According to political scientist Gayle T. Tate in her book, Unknown Tongues: Black Women's Political Activism in the Antebellum Era, 1830-1860, the society continued its financial support with annual contributions throughout the 1840s.[14] Tate maintains the Forten women's leadership and support led to the continuous contributions to the school. This reinforces the contention that black women played in integral leadership role within the PFASS.

The PFASS also raised money for clothing, shelter, and food to aid fugitive slaves. Black women members under the leadership of Hetty Reckless worked closely with the Vigilance Association of Philadelphia, an all-male benevolent society that aided fugitive slaves. Reckless "persuaded society members to contribute to community projects and to make donations ... to provide fugitives with room and board, clothing, medical assistance, employment, financial aid, and advice concerning their legal rights."[15] However, white female members of the society were quite divided over whether aid to fugitive slaves counted as true antislavery work. Lucretia Mott believed this activity was not the role of the PFASS.[16] This division illustrates a difference in abolitionist agendas that began to emerge among the two races.[17] Unlike their white female counterparts, black women, in an effort that Tate labels "pragmatic abolitionism," viewed subversive strategies like aiding fugitive slaves as compatible with the open challenges preferred by white abolitionists.[18] White female abolitionists, on the other hand, tended to view these actions as "potential distractions from the main goal of fighting slavery."[19]

Birth of women's rights

As women played a pertinent role in the abolitionist movement, white and black members of the PFASS supported the radical idea of granting women the right to vote and to perform traditionally male roles such as speaking in public.[20] Writing in the late 1970s, historian Ira V. Brown identifies the women of the PFASS as playing a key role in the development of American feminism or what she labels as the "cradle of feminism." Brown primarily focuses on the society's white female leadership and the key roles these women played in the eventual birth of the women's movement beginning at the Seneca Falls Convention.[21] More recent additions to the historiography of female abolitionist societies incorporates the collective role of free black females. Shirley Yee asserts that black female community activists like those in the PFASS helped shape black women's community activism for later generations, especially in the modern civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.[22]

In popular culture

- Ain Gordon's 2013 play If She Stood, commissioned by the Painted Bride Art Center in Philadelphia, takes place at a fictional meeting of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society.[23]

References

Notes

- "Mary Ann M'Clintock". Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Smith, Jessie Carney and Wynn, Linda T. Freedom Facts and Firsts: 400 Years of the African American Civil Rights Experience Visible Ink Press, 2009. p. 242. ISBN 9781578592609

- Christian, Charles M. and Bennett, Sari. Black Saga: The African American Experience: A Chronology Basic Civitas Book, 1998. p. 1833. ISBN 9781582430003.

- Brown, Ira V. (Ira Vernon), 1922- (1991). Mary Grew, abolitionist and feminist, 1813-1896. Selinsgrove [Pa.]: Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 0-945636-20-2. OCLC 23217312.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Soderlund, pp. 69, 74

- Yee, pp. 90, 95

- Gordon, Ann D. (ed.) et al. African American Women and the Vote: 1837-1965 University of Massachusetts Press, 1997. p. 33. ISBN 1558490582.

- Sumler-Lewis, Janice (Winter 1981–1982). "The Forten-Purvis Women of Philadelphia and the American Anti-Slavery Crusade". Journal of Negro History. 66 (4): 281–288. doi:10.2307/2717236. JSTOR 2717236. S2CID 152092689.

- Winch, Julie (1994). "'You Have Talents-Only Cultivate Them', Philadelphia's Black Female Literacy Societies and the Abolitionist Crusade". In Jean Fagan Yellin; John C. VanHorne (eds.). The Abolitionist Sisterhood. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 105–117.

- Dionne, Evette (2020). Lifting as we climb : Black women's battle for the ballot box. New York. ISBN 978-0-451-48154-2. OCLC 1099569335.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Salerno, p. 68

- Soderlund, pp. 80–82

- Soderlund, pp. 83-84

- Tate, p. 192

- Tate, p. 212

- Yee, p. 99

- Salerno, pp. 140-1

- Tate, p. 213

- Salerno, p. 141

- Yee, p. 104

- Brown, Ira V. (April 1978). "Cradle of Feminism: The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, 1833-1840". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 102: 142–166.

- Yee, p. 157

- Salisbury, Stephen. "Painted Bride productions on 19th century women touch familiar issues" Philadelphia Inquirer (April 26, 2013)

Bibliography

- Salerno, Beth A. (2005). Sister Societies. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University. ISBN 9780875803388.

- Soderlund, Jean R. (1994). "Priorities and Power: The Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society". In Jean Fagan Yellin; John C. VanHorne (eds.). The Abolitionist Sisterhood. Cornell University Press.

- Tate, Gayle T. (2003). Unknown Tongues: Black Women's Political Activism in the Antebellum Era, 1830-1860. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Yee, Shirley J. (1992). Black Women Abolitionists: A Study in Activism, 1828-1860. University of Tennessee Press.

External links

- "Our Sphere of Influence: Women Activists and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society" Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- "Cradle of Feminism, The Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, 1833-1840" Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (April 1978)

- "Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society Historical Marker" on ExplorePAhistory.com

- "The Anti-Slavery Alphabet. Philadelphia: Printed for the Anti-Slavery Fair, 1846" Mississippi Department of Archives and History