Phantom border

A phantom border (German: Phantomgrenze) is an informal delineation following the approximate course of an abolished political border, associated with demographic differences on each side as a continuing legacy of historical division, despite official geopolitical union.[1] Not all former political borders are today phantom borders. Factors that may increase the likelihood of a political border becoming a phantom border upon dissolution, include: short time elapsed since the border's dissolution, long existence of the former border, imporousity of the former border, and divergent characteristics of the political entity formerly governing one side of the border.

Phantom borders have many different implications: in Ukraine they are associated with conflict, while in countries such as Romania they play an important part in relations with neighboring countries.[2]

Development of the concept

Though the phenomenon of phantom borders is ancient, articulation of the concept is recent, stemming from its identification in the Phantomgrenzen project (also known as the Phantom Borders in East Central Europe Project, a now-defunct European border studies research network backed by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research), which defines the phenomenon as "former, predominantly political borders that structure today’s world (…), historical spaces [that] persist or re-emerge”.[3] Recent developments in border studies have led to borders being understood more under the lens of being social constructs (such as in the work of Vladimir Kolosov).[4] From the modern perspective, phantom borders are marks of the past and reminders of previous conquests and annexations. Nail Alkan states that this "enclosure fosters a feeling of security and people prefer to live in familiar circumstances" where old political borders were.[2]

Notable phantom borders

Germany

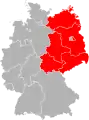

The borders of Prussia and East Germany are reflected in support for far-right or national conservative parties after German unification, including DNVP in the Weimar Republic and AfD in the 21st century.[5][6] East Germany notably did not receive as much immigration, except Russians, during the Cold War, so East Germans, particularly Russian-Germans, post-unification are more opposed to it. Combined with East German Ostalgie and the perception by East Germans of being second-class citizens compared to West Germans, eastern regions of Germany tend to vote more for either left-wing parties like The Left and PDS or right-wing anti-immigration parties like AfD.[7] Other consequences of the German East-West divide show themselves in different ways - In the west, workers earn higher wages and produce more, while unemployment is higher in the east. The divide is also reflected in personal preferences - in terms of car preferences, West Germans prefer BMW over Škoda, while the opposite is the case in the East.[8]

Partition of Germany, 1945–1990

Partition of Germany, 1945–1990 Religion in Germany. Blue represents majority-Protestant regions, green represents majority-Catholic regions, and red represents majority-irreligious regions.

Religion in Germany. Blue represents majority-Protestant regions, green represents majority-Catholic regions, and red represents majority-irreligious regions.

Poland

Historically, Poland was partitioned multiple times between the German Empire/Prussia, the Habsburg Empire, and the Russian Empire. Under Prussian control were the Polish regions of eastern Pomorze, Wielkopolska and Upper Silesia, regions historically exposed to German influence. Russia controlled central Poland under Congress Poland, including the capital, Warsaw, and Austria controlled the southern regions under the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. Both regions had large, mostly dominant populations of Polish people.[9] At the end of the Second World War, German territories up to the Oder–Neisse line were handed over to Poland as compensation for the annexation of eastern Poland by the Soviet Union.[2]

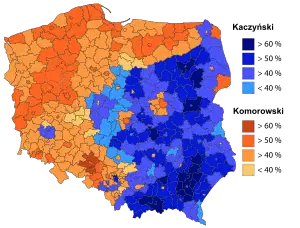

Politically, this led to the creation of phantom borders. Coinciding with the Prussian-controlled regions, western Poland is known as Polska liberalna, or "liberal Poland", due to their opting to vote for liberal or social-democratic parties such as PO in elections. In central and southern Poland, the situation is different: the region is known as Polska solidarna, or "solidarity Poland", where voters vote more to the conservative side, represented by parties such as PiS.[10] This split can be explained through the influences foreign empires had on the Polish people, such as the ones caused by Germanization and Russification programs and different languages, economic models, political traditions, and cultures within these different empires, which affect the industrialization and infrastructure density of regions, re-settlement of the population of Eastern Poland up to the Oder-Neisse line, and social norms and values.[2]

Territorial changes of Poland from 1635 to 2009

Territorial changes of Poland from 1635 to 2009 Results of the first round of the 2010 Polish presidential election

Results of the first round of the 2010 Polish presidential election

Romania

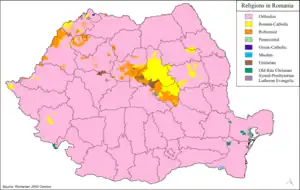

Prior to Romanian independence, its modern territories consisted of Wallachia and Moldavia under the Ottoman Empire, and the broader region of Transylvania under Habsburg Austria. Transylvania, in general, has more ethnic diversity than other parts of Romania, with a significant Hungarian minority and a smaller German one. Perceptions of political and social powers are also different, as Transylvania was ruled under administrative authorities while the former Ottoman lands were under more arbitrary rule with less centralization of legal powers. Transylvania experiences a larger number of political protests than the rest of the country excluding the capital Bucharest.[11]

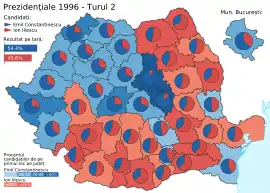

Formerly Ottoman Romania had been struggling for full independence, while Habsburg Romanians tended to go for political reforms. The faultline, separated by the Carpathian Mountains, is sometimes considered as the line separating the Eastern Orthodox Church in the east and the Latin Church to the west. Throughout the 1970s, Nicolae Ceaușescu implemented policies to assimilate minorities in Transylvania, though the cultural divide still remained. During Romania's elections in the 1990s, Transylvanian residents were less supportive of nationalic and populistic parties. In 1996, liberal presidential candidate Emil Constantinescu won in nearly all of Transylvania, while incumbent and former communist politician Ion Iliescu won in nearly all regions outside it.[12]

Extent of Transylvania within Romania

Extent of Transylvania within Romania Results of the run-off of the 1996 Romanian presidential election

Results of the run-off of the 1996 Romanian presidential election Dominant Christian denominations in Romania

Dominant Christian denominations in Romania

Ukraine

In just the last 150 years, parts of Ukraine have been split between Russia, the Habsburg Empire, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, Hungary, and various iterations of a Ukrainian state. There has been noted a divide between different regions of Ukraine originating from political boundaries in the region – electorally, there is a split between eastern-southern and central-western Ukraine. One example of phantom borders would be the pro-Russian attitude of Dnieper Ukraine due to its longer connections with Russia. There are various anomalies in these phantom borders – an example would be that voters in the regions of Transcarpathia and Chernivtsy, previously controlled by Austria, seem to vote similarly to eastern Ukraine.[13]

.PNG.webp) Results of the 2007 Ukrainian parliamentary election

Results of the 2007 Ukrainian parliamentary election

References

- Zajc, Marko. "Contemporary Borders as ‘Phantom Borders’. An Introduction", Südosteuropa 67, 3 (2019): 297-303, doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2019-0023

- Jańczak, Jaroslaw. "Phantom borders and electoral behaviour in Poland.", Erdkunde 69, 2 (2015): 125-137, doi: https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2015.02.03

- Phantomgrenzen Project. Phantomgrenzen English Flyer (PDF). Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Kolosov, Vladimir & Więckowski, Marek. "Border changes in Central and Eastern Europe: An Introduction". Geographia Polonica 91, 5-16 (2018): 5-16, doi: https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0106.

- Hawes, James (6 November 2019). "It wasn't the Berlin Wall that divided Germany". UnHerd. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "How the attitudes of West and East Germans compare, 30 years after fall of Berlin Wall". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Germany's East-West Divide Fuels the Far Right". Fair Observer. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "East-West divide still exists in Germany". EUobserver. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Partitions of Poland". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- "Two Nations?". Concilium Civitas. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Rammelt, Henry (30 June 2015). "Shadows of the past: Common effects of communism or different pre-communist legacies? An analysis of discrepancies in social mobilization throughout Romanian regions". Erdkunde. 69 (2): 151–160. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.2015.02.05.

- Roper, Steven D.; Fesnic, Florin (January 2003). "Historical Legacies and Their Impact on Post-Communist Voting Behaviour". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (1): 119–131. doi:10.1080/713663449. S2CID 55464242.

- van Löwis, Sabine. "Phantom Borders in the Political Geography of East Central Europe: An Introduction". Erdkunde 69, 2 (2015): 99-106, doi: https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2015.02.01.