Phantasmagoria

Phantasmagoria (ⓘ), alternatively fantasmagorie and/or fantasmagoria was a form of horror theatre that (among other techniques) used one or more magic lanterns to project frightening images, such as skeletons, demons, and ghosts, onto walls, smoke, or semi-transparent screens, typically using rear projection to keep the lantern out of sight. Mobile or portable projectors were used, allowing the projected image to move and change size on the screen, and multiple projecting devices allowed for quick switching of different images. In many shows, the use of spooky decoration, total darkness, (auto-)suggestive verbal presentation, and sound effects were also key elements. Some shows added a variety of sensory stimulation, including smells and electric shocks. Such elements as required fasting, fatigue (late shows), and drugs have been mentioned as methods of making sure spectators would be more convinced of what they saw. The shows started under the guise of actual séances in Germany in the late 18th century and gained popularity through most of Europe (including Britain) throughout the 19th century.

The word "phantasmagoria" has also been commonly used to indicate changing successions or combinations of fantastic, bizarre, or imagined imagery.[1]

Etymology

From French phantasmagorie, from Ancient Greek φάντασμα (phántasma, “ghost”) + possibly either αγορά (agorá, “assembly, gathering”) + the suffix -ia, or ἀγορεύω (agoreúō, “to speak publicly”).

Paul Philidor (also known simply as "Phylidor") announced his show of ghost apparitions and evocation of the shadows of famous people as Phantasmagorie in the Parisian periodical Affiches, annonces et avis divers of December 16, 1792. About two weeks earlier the term had been the title of a letter by a certain "A.L.M.", published in Magazin Encyclopédique. The letter also promoted Phylidor's show.[2] Phylidor had previously advertised his show as Phantasmorasi in Vienna in March 1790.[3]

The English variation Phantasmagoria was introduced as the title of M. De Philipsthal's show of optical illusions and mechanical pieces of art in London in 1801.[4] De Philipsthal and Philidor are believed to have been the same person.

History

Prelude (before 1750)

_giovanni_da_fontana_(probably)_-_apparentia_nocturna_ad_terrorem_videntiumR.jpg.webp)

Some ancient sightings of gods and spirits are thought to have been conjured up by means of (concave) mirrors,[5] camera obscura, or magic lantern projections. By the 16th century, necromantic ceremonies and the conjuring of ghostly apparitions by charlatan "magicians" and "witches" seemed commonplace.[6]

In the 1589 version of Magia Naturalis, Giambattista della Porta described how to scare people with a projected image. A picture of anything that would terrify the beholder should be placed in front of a camera obscura hole, with several torches around it. The image should be projected onto a sheet hanging in the middle of the nascent dark chamber, where spectators wouldn't notice the sheet but only see the projected image hanging in the air.[7]

In his 1613 book Opticorum Libri Sex,[8] Belgian Jesuit mathematician, physicist and architect François d'Aguilon described how some charlatans cheated people out of their money by claiming they knew necromancy and would raise the specters of the devil from hell and show these to the audience inside a dark room. The image of an assistant with a devil's mask was projected through a lens into the dark room, scaring the uneducated spectators.[9]

The earliest pictures known to have been projected with lanterns were images of Death, hell, or monsters:

- Giovanni Fontana's 1420 drawing showed a lantern projecting a winged female demon.

- Athanasius Kircher warned in his 1646 edition of Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae that impious people could abuse his stenographic mirror projection system by painting a picture of the devil on the mirror and projecting it into a dark place to force people to carry out wicked deeds.[10] His pupil Gaspar Schott later turned this into the idea that it could be easily used to keep godless people from committing many sins, if a picture of the devil was painted on the mirror and thrown onto a dark place.[11]

Huygens' 1659 sketches for a projection of Death taking off his head

Huygens' 1659 sketches for a projection of Death taking off his head - In 1659 Dutch inventor Christiaan Huygens drew several phases of Death removing his skull from his neck and putting it back again, sketches meant to be projected with "convex lenses and a lamp".[12] This lamp later became known as the magic lantern, and the sketches form the oldest known extant documentation of this invention.

- One of Christiaan Huygens' contacts wrote to him in 1660: "The good Kircher is always performing tricks with the magnet at the gallery of the Collegium Romanum; if he would know about the invention of the Lantern he would surely frighten the cardinals with specters."[13]

- Thomas Rasmussen Walgensten's 1664 lantern show prompted Pierre Petit to call the device "laterne de peur" (lantern of fear). In 1670 Walgensten projected an image of Death at the court of King Frederick III of Denmark.[14]

- In 1668, Robert Hooke wrote about a type of magic lantern installation: "It produces effects not only very delightful, but to such as know not the contrivance very wonderful; so that spectators not well versed in optics, that should see the various apparitions and disappearances, the motions, changes and actions that may this way be represented, would readily believe them to be supernatural and miraculous."[15]

- In the 1671 second edition of Kircher's Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae.,[16] the magic lantern was illustrated with projections of Death and a person in purgatory or hellfire. Kircher did suggest in his book that an audience would be more astonished by the sudden appearance of images if the lantern would be hidden in a separate room, so the audience would be ignorant of the cause of their appearance.[17] According to legend Kircher secretly used the lantern at night to project the image of Death on windows of apostates to scare them back into church,[18] but this is probably based on Gaspar Schott's suggestion (see above).

- In 1672, French physician and numismatist Charles Patin was very impressed with the lantern show that "Monsieur Grundler" (Griendel) performed for him in Nuremberg: "He even stirs the shadows at his pleasure, without the aid of the underworld. (...) My esteem for his knowledge could not prevent my fright, I believed there never was a greater magician than him in the world. I experienced paradise, I experienced hell, I experienced specters. I have some constancy, but I would have willingly given one half to save the other." After these apparitions Griendel showed other subjects in this performance, including birds, a palace, a country-wedding and mythical scenes.[19] Patin's elaborate description of an early lantern show seems to be the oldest to contain more than frightening pictures.

While surviving slides and descriptions of lantern shows from the following decades included numerous subjects, scary pictures remained popular.[14]

Late 18th century

The last decades of the 18th century saw the rise of the age of Romanticism and the Gothic novel. There was an obsession with intense emotions (including fear), the irrational, the bizarre, and the supernatural. The popular interest in such topics explained the rise and, more specifically, the success of phantasmagoria for the productions to come.[20]

The magic lantern was a good medium with which to project fantasies as its imagery was not as tangible as in other media. Since demons were believed to be incorporeal, the magic lantern could produce very fitting representations.[21]

When magicians started to use the magic lantern in shows, some special effects were thought up. French physician, inventor and manufacturer of conjuring apparatus and scientific instruments Edmé-Gilles Guyot described several techniques in his 1770 book Nouvelles récréations physiques et mathématiques, including the projection of ghosts on smoke.[22]

Johann Georg Schrepfer

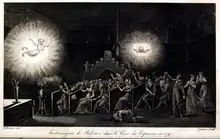

In the early 1770s in Leipzig, Germany, coffeehouse owner, charlatan, necromancer, and leader of an independent Freemason lodge Johann Georg Schrepfer (or Schröpfer) performed ghost-raising séances and necromantic experiments for his Freemason lodge. For typical necromantic activity, he demanded his followers remain seated at a table or else face terrible dangers.

He made use of a mixture of Masonic, Catholic, and Kabbalistic symbolism, including skulls, a chalk circle on the floor, holy water, incense, and crucifixes. The spirits he raised were said to be clearly visible, hovering in the air, vaporous, and sometimes screaming terribly. The highlight of his career was a séance for the court in the Dresden palace early in the summer of 1774. This event was impressive enough to still be described more than a century later in Germany and Britain.

Apparitions reportedly raised by Schrepfer over the years included Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, the beheaded Danish "traitors" Johann Friedrich Struensee and Enevold Brandt with their heads in their hands, and the Knights Templars' last Grand Master Jacques de Molay. During a séance in Dresden, Schrepfer ordered De Molay's spirit to take a letter to a companion in Frankfurt. De Molay obeyed and returned half an hour later with an answer signed in Frankfurt by the companion. Another spirit appeared engulfed in flames begging Schrepfer not to torture him so.[23]

In the early morning of October 8, 1774, Schrepfer reportedly committed suicide with a pistol in a park with five friends present. According to legend he was a victim of delusions about his necromantic abilities and convinced he could resurrect himself afterwards. However, there are several indications that he may actually have been murdered.[24]

Most spectators of Schrepfer's séances were convinced that the apparitions they saw were real. No clear evidence of deceit seems to ever have been found, but critics have described several suspicions. The techniques that Schrepfer reportedly used for his elaborate effects included actors performing as ghosts, ventriloquism, hidden speaking tubes, glass harmonica sounds, aromatic smoke, camera obscura projections and/or magic lantern projections on smoke, concave mirror projections, and staged thunder.[25]

Schrepfer had been friends with pharmacist and Freemason Johann Heinrich Linck the Younger and regularly held lodge meetings at Linck's garden house. Linck could have been helping Schrepfer with drugs and chemicals and also knew about the workings of optical and acoustic devices. Linck owned a magic lantern which was decorated with a crucifix and a skull with wings.[26]

Soon after Schrepfer's death, there was a boom of publications attacking or defending his supposed abilities to raise ghosts, expanding Schrepfer's fame across Europe. Several publications included explanations of techniques he might have used to conjure apparitions, which inspired several people to recreate Schrepfer's séances. Christlieb Benedikt Funk, Professor of Physics at the Leipzig University, was possibly the first to publicly recreate such ghost-raising demonstrations; however, he was ordered to stop by the university's authorities.[27]

Physicist Phylidor

The magician "physicist" Phylidor, also known as "Paul Filidort" and probably the same as Paul de Philipsthal, created what may have been the first true phantasmagoria show in 1790. After a first ghost-raising session in Berlin in 1789 led to accusations of fraud and expulsion from Prussia, Phylidor started to market his necromantic shows as an art that revealed how charlatans fooled their audiences.[28] His improved show, possibly making use of the recently invented Argand lamp,[29] was a success in Vienna from 1790 to 1792. Phylidor advertised these shows as "Schröpferischen, und Cagliostoischen Geister-Erscheinungen" (Schröpfer-esque and Cagliostro-esque Ghost Apparitions)[30] and as "Phantasmorasi".[3]

Renowned German showman Johann Carl Enslen (1759–1848) is thought to have purchased Philidor's equipment when Phylidor left Vienna in 1792. He presented his own phantasmagoria shows in Berlin, with the King of Prussia attending a show on 23 June 1796. Enslen moved the lantern to produce the illusion of moving ghosts and used multiple lanterns for transformation effects. There were other showmen who followed in Phylidor's footsteps, including "physicist" Von Halbritter who even adapted the name of Phylidor's shows as "Phantasmorasie – Die natürliche Geister-Erscheinung nach der Schröpferischen Erfindung".[27]

From December 1792 to July 1793 "Paul Filidort" presented his "Phantasmagorie" in Paris,[27][31] probably using the term for the first time. It is assumed Etienne-Gaspard Robertson visited one of these shows and was inspired to present his own "Fantasmagorie" shows a few years later.[32]

In October 1801 a phantasmagoria production by Paul de Philipsthal opened in London's Lyceum Theatre in the Strand, where it became a smash hit.

Robertson

Étienne-Gaspard "Robertson" Robert, a Belgian inventor and physicist from Liège, became the best known phantasmagoria showman. He is credited for coining the word fantascope, and would refer to all of his magic lanterns by this term.[33] The fantascope was not a magic lantern that could be held by hand, but instead required someone to stand next to it and physically move the entire fantascope closer or further to the screen.[33] He would often eliminate all sources of light during his shows in order to cast the audience in total darkness for several minutes at a time.[33] Robertson would also lock the doors to the theater so that no audience member could exit the show once it had started.[33] He was also known for including multiple sound effects into his show, such as thunder clapping, bells ringing, and ghost calls. Robertson would pass his glass slides through a layer of smoke while they were in his fantascope, in order to create an image that looked out of focus.[33] Along with the smoke, he would also move most of his glass slides through his fantascope very quickly in order to create the illusion that the images were actually moving on screen.[33]

Robertson's first "Fantasmagorie" was presented in 1797 at the Pavillon de l'Echiquier in Paris.[34] The macabre atmosphere in the post-revolutionary city was perfect for Robertson's Gothic extravaganza complete with elaborate creations and Radcliffean décor.

After discovering that he could put the magic lantern on wheels to create either a moving image or one that increased and decreased in size, Robertson moved his show. He sited his entertainment in the abandoned cloisters kitchen of a Capuchin convent (which he decorated to resemble a subterranean chapel) near the Place Vendôme. He staged hauntings, using several lanterns, special sound effects and the eerie atmosphere of the tomb. This show lasted for six years, mainly because of the appeal of the supernatural to Parisians who were dealing with the upheavals as a result of the French Revolution. Robertson mainly used images surrounded by black in order to create the illusion of free-floating ghosts. He also would use multiple projectors, set up in different locations throughout the venue, in order to place the ghosts in environments. For instance, one of his first phantasmagoria shows displayed a lightning-filled sky with both ghosts and skeletons receding and approaching the audience. In order to add to the horror, Robertson and his assistants would sometimes create voices for the phantoms.[20] Often, the audience forgot that these were tricks and were completely terrified:

I am only satisfied if my spectators, shivering and shuddering, raise their hands or cover their eyes out of fear of ghosts and devils dashing towards them.

— Étienne-Gaspard Robert

In fact, many people were so convinced of the reality of his shows that police temporarily halted the proceedings, believing that Robertson had the power to bring Louis XVI back to life.[20]

United States

Phantasmagoria came to the United States in May 1803 at Mount Vernon Garden, New York. Much like the French Revolution sparked interest in phantasmagoria in France, the expanding frontier in the United States made for an atmosphere of uncertainty and fear that was ideal for phantasmagoria shows.[20] Many others created phantasmagoria shows in the United States over the next couple of years, including Martin Aubée, one of Robertson's former assistants.

Further history

Thomas Young proposed a system that could keep the projected image in focus for a lantern on a small cart with rods adjusting the position of the lens when the cart was wheeled closer or further away from the screen.[35]

John Evelyn Barlas was an English poet who had written for several phantasmagoria shows during the late 1880s. He used the pseudonym Evelyn Douglas for most of the works written for phantasmagoria.[36] He has written several different works, most of them focusing on the idea of dreams and nightmares. Some of his works include Dreamland, A Dream of China, and Dream Music.[36] His work is known for including extravagant descriptions of settings with multiple colors. Most of Barlas' work also mentions flames and fire. The flames are meant to represent the burning of emotions laced throughout Barlas' poems, and fit well within the realm of phantasmagoria.

By the 1840s phantasmagoria became already outmoded, though the use of projections was still employed, just in different realms:

...although the phantasmagoria was an essentially live form of entertainment these shows also used projectors in ways which anticipated 20th century film-camera movements—the 'zoom', 'dissolve', the 'tracking-shot' and superimposition.

— Mervyn Heard

In other media

Before the rise of phantasmagoria, interest in the fantastic was apparent in ghost stories. This can be seen in the many examples of ghost stories printed in the 18th century, including Admiral Vernon's ghost; being a full true and particular Account as how a Warlike apparition appeared last Week to the Author, Clad all in Scarlet, And discoursed to him concerning the Present State of Affairs (1758). In this tale, the author's reaction to the ghost he sees is much like that of the audience members at the phantasmagoria shows. He says that he is "thunderstruck", and that "astonishment seized me. My bones shivered within me. My flesh trembled over me. My lips quaked. My mouth opened. My hands expanded. My knees knocked together. My blood grew chilly, and I froze with terror."[37]

French painters of the time, including Ingres and Girodet, derived ideas for paintings from the phantasmagoria, and its influence spread as far as J. M. W. Turner.[38]

Walter Benjamin was fascinated by the phantasmagoria and used it as a term to describe the experience of the Arcades in Paris. In his essays, he associated phantasmagoria with commodity culture and its experience of material and intellectual products. In this way, Benjamin expanded upon Marx's statement on the phantasmagorical powers of the commodity.[39]

Early stop trick films developed by Georges Méliès most clearly parallel the early forms of phantasmagoria. Trick films include transformations, superimpositions, disappearances, rear projections, and the frequent appearance of ghosts and apparent decapitations.[40] Modern-day horror films often take up many of the techniques and motifs of stop trick films, and phantasmagoria is said to have survived in this new form.

Maria Jane Jewsbury produced a volume entitled Phantasmagoria, or Sketches of Life and Literature, published by Hurst Robinson & Co, in 1825. This consists of a number of essays on various subjects together with poetry. The whole is dedicated to William Wordsworth.

Phantasmagoria is also the title of a poem in seven cantos by Lewis Carroll that was published by Macmillan & Sons in London in 1869, about which Carroll had much to say. He preferred that the title of the volume be found at the back, saying in a correspondence with Macmillan, "it is picturesque and fantastic—but that is about the only thing I like…" He also wished that the volume would cost less, thinking that the 6 shillings was about 1 shilling too much to charge.[41]

Phantasmagoria's influence on Disney can be found in the countless effects throughout the themed lands and attractions at the theme parks but are likely most memorable in the practical and projection effects of the Haunted Mansion (at Disneyland, Walt Disney World and Tokyo Disneyland), and Phantom Manor (at Disneyland Paris), as well live shows such as Fantasmic (at Disneyland and Disney's Hollywood Studios), which feature film/video projections on water screens.

A series of photographs taken from 1977 to 1987 by photographer and model Cindy Sherman are described as portraying the phantasmagoria of the female body. Her photographs include herself as the model, and the progression of the series as a whole presents the phantasmagoric space projected both onto and into the female body.[42]

The 1995 survival-horror video game Phantasmagoria is partly based upon these performances. In the game, several flashbacks are shown to fictional phantasmagorias performed by the magician Zoltan "Carno" Carnovasch. However, unlike the real shows, his are much more graphic and violent in nature and involve actual demons instead of projected ones.

In modern times

A few modern theatrical troupes in the United States and United Kingdom stage phantasmagoria projection shows, especially at Halloween.

From February 15 to May 1, 2006, the Tate Britain staged "The Phantasmagoria" as a component of its show "Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination." It recreated the content of the 18th and 19th century presentations, and successfully evoked their tastes for horror and fantasy.[43]

In 2006, David J. Jones discovered the precise site of Robertson's show at the Capuchin convent.[44]

References

- "Definition of PHANTASMAGORIA". www.merriam-webster.com.

- Magazin Encyclopédique. 1792-12-03.

- Phylidor Phantasmorasi handbill. 1792-03

- Paul de Philipsthal Phantasmagoria 1801 handbill

- "The Magic Lantern, Dissolving Views, and Oxy-Hydrogen Microscope described, etc". 1866.

- Ruffles, Tom (2004-09-27). Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife. pp. 15–17. ISBN 9780786420056.

- "Natural magick". 1658.

- d'Aguilon, François (1613). Opticorum Libri Sex philosophis juxta ac mathematicis utiles (in Latin). Antverpiæ : Ex officina Plantiniana, apud Viduam et filios J. Moreti. p. 47.

- Mannoni, Laurent (2000). The great art of light and shadow. p. 10. ISBN 9780859895675.

- Gorman, Michael John (2007). Inside the Camera Obscura (PDF). p. 49.

- Schott, Kaspar (1677). "Magia optica – Kaspar Schott". Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- Huygens, Christiaan. "Pour des representations par le moyen de verres convexes à la lampe" (in French).

- letter from Pierre Guisony to Christiaan Huygens (in French). 1660-03-25.

- Rossell, Deac (2002). "The Magic Lantern".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, from Their ..." 1809. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- Kircher, Athanasius (1671). Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (in Latin). pp. 767–769. ISBN 9788481218428. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- Kircher, Athanasius; Rendel, Mats. "About the Construction of The Magic Lantern, or The Sorcerers Lamp".

- "The miracle of the magic lantern". www.luikerwaal.com.

- Patin, Charles (1674). Relations historiques et curieuses de voyages (in French).

- Barber, Theodore X (1989). Phantasmagorical Wonders: The Magic Lantern Ghost Show in Nineteenth-Century America Film History 3,2. pp. 73–86.

- Vermeir, Koen. The magic of the magic lantern (PDF).

- "Nouvelles récréations physiques et mathématiques, contenant ce qui a été imaginé de plus curieux dans ce genre et qui se découvre journellement, auxquelles on a joint, leurs causes, leurs effets, la mani¿ere de les construire, & l'amusement qu'on en peut tirer pour étonner et surprendre agréablement". 2010-07-21. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- Geffarth, Renko (2007). The Masonic Necromancer: Shifting Identities In The Lives Of Johann Georg Schrepfer. pp. 181–195. ISBN 978-9004162570.

- Otto Werner Förster: Tod eines Geistersehers. Johann Georg Schrepfer. Eine vertuschte sächsische Staatsaffäre, 1774. Taurus Verlag Leipzig, 2011

- Rossell, Deac. The Magic Lantern.

- Förster, Otto Werner (2011). Schrepfer und der Leipziger Löwenapotheker Johann Heinrich Linck (in German). Archived from the original on 2013-11-02.

- Rossell, Deac (2001). The 19 Century German Origins of the Phantasmagoria Show.

- Seyfried, Heinrich Wilhelm (1789). Chronic von Berlin oder Berlinische Merkwürdigkeiten – Volume 5 (in German).

- Grau, Oliver. Remember the Phantasmagoria! chapter from MediaArtHistories, MIT Press/Leonardo Books, 2007, p. 144

- Phylidor Schröpferischen, und Cagliostoischen Geister-Erscheinungen flyer 1790

- Affiches, annonces et avis divers. 1793-07-23

- Mervyn Heard, Phantasmagoria (2006), p. 87.

- Barber, Theodore (1989). Phantasmagorical Wonders: The Magic Lantern Ghost Show in Nineteenth-Century America. Online: Indiana University Press. pp. 73–75.

- Castle, Terry. "Phantasmagoria and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie." The Female Thermometer. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1995. 140–167. Print.

- Brewster, David (1843). Letter on Natural Magic. Harper & Brothers. pp. 160–161.

thomas young phantasmagoria.

- Douglas, Evelyn (1887). Phantasmagoria. Chelmsford: J.H. Clarke. p. 65.

- "Admiral Vernon's ghost; being a full true and particular Account as how a Warlike apparition appeared last Week to the Author, Clad all in Scarlet, And discoursed to him concerning the Present State of Affairs" Printed for E. Smith, Holborn (1758): 1–8. Print."

- Michael Charlesworth, Landscape and Vision in 19th century Britain and France (Ashgate, 2008), Chapter Two, "Ghosts and Visions".

- Cohen, Margaret. "Walter Benjamin's Phantasmagoria." New German Critique 48 (1989): 87–107. Print.

- "Overview of Edison Motion Pictures by Genre". The Library of Congress. The Library of Congress, 13 Jan 1999. Web.

- Cohen, Morton N. "Lewis Carroll and the House of Macmillan". Cambridge University Press 7 (1979):31–70. Print.

- Mulvey, Laura. "A Phantasmagoria of the Female Body: The Work of Cindy Sherman." New Left Review I.188 (July–August 1991): 137–150. Web.

- "Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination – Exhibition at Tate Britain".

- J. Jones, David (2011). Gothic machine textualities, pre-cinematic media and film in popular visual culture, 1670–1910. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-2407-3. OCLC 1113318517.

Further reading

- Castle, Terry (1995). The Female Thermometer: 18th-Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508097-1.

- Grau, Oliver (2007). "Remember the Phantasmagoria! Illusion Politics of the Eighteenth Century and its Multimedial Afterlife", Oliver Grau (Ed.): Media Art Histories, MIT Press/Leonardo Books, 2007.

- Guyot, Edme-Gilles (1755). Nouvelles Recréations Physiques et Mathématiques translated by Dr. W. Hooper in London (1st ed. 1755)

- "Robertson" (Robert, Étienne-Gaspard) (1830–34). Mémoires récréatifs, scientifiques et anecdotiques d'un physicien-aéronaute.

- David J. Jones(2011). 'Gothic Machine: Textualities, Pre-Cinematic Media and Film in Popular Visual Culture, 1670–1910', Cardiff: University of Wales Press ISBN 978-0708324073

- David J Jones (2014). 'Sexuality and the Gothic Magic Lantern, Desire, Eroticism and Literary Visibilities from Byron to Bram Stoker', Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 9781137298911.

- Douglas, Evelyn. Phantasmagoria. 1st ed. Vol. 1. Chelmsford: J. H. Clarke, 1887. Print.

- Barber, Theodore. Phantasmagorical Wonders: The Magic Lantern Ghost Show in Nineteenth-Century America. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. N.p.: Indiana UP, 1989. Print.

External links

Media related to Phantasmagoria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Phantasmagoria at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of phantasmagoria at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of phantasmagoria at Wiktionary- Mervyn Heard's "Phantasmagoria: The Secret Life of the Magic Lantern"

- Adventures in Cybersound: "Robertson's Phantasmagoria"

- Mervyn Heard's short history of the Phantasmagoria

- Visual Media site with much pre-cinema information

- Another short history, with more description of Philipstal's shows in London

- Burns, Paul The History of the Discovery of Cinematography An Illustrated Chronology

- Utsushi-e (Japanese Phantasmagoria)

- Esther Leslie on Benjamin's Arcades Project

- The Museum of Precinema Precinema Museum, Italy. Collection includes original Phantasmagoria magic lanterns and slides