Phaedrus (Athenian)

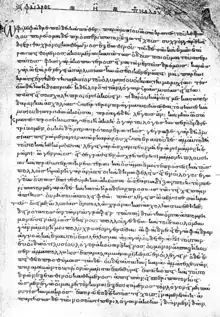

Phaedrus (/ˈfiːdrəs, ˈfɛdrəs/), son of Pythocles, of the Myrrhinus deme (Greek: Φαῖδρος Πυθοκλέους Μυῤῥινούσιος, Phaĩdros Puthokléous Murrhinoúsios; c. 444 – 393 BC), was an ancient Athenian aristocrat associated with the inner-circle of the philosopher Socrates. He was indicted in the profanation of the Eleusinian Mysteries in 415 during the Peloponnesian War, causing him to flee Athens.

He is best remembered for his depiction in the dialogues of Plato. His philosophically erotic role in his eponymous dialogue and the Symposium inspired later authors, from the ancient comedic playwright Alexis[1] to contemporary philosophers like Robert M. Pirsig and Martha Nussbaum.[2]

Life

Phaedrus, whose name translates to "bright" or "radiant" in particular how one might show light on something, "to reveal" at its earliest etymology,[3] was born to a wealthy family sometime in the mid-5th century BC, and was the first cousin of Plato's stepbrother Demos.[1] All sources remember him as an especially attractive young man.[4] His depiction in the writing of Plato has led scholars to assume that he did not have his own system of philosophy, despite his interest in such contemporaneous movements as rhetoric, tragedy and sophism.[1] He is present for the speeches delivered in Plato's Protagoras,[5] whose dramatic date of 433/432[1] suggests that Phaedrus was involved in prominent Athenian intellectual circles from a young age; the dialogue also notes his early interest in astronomy and long-standing friendship with the physician Eryximachus.[3] The Symposium's certain dramatic date of 416 suggests his close association with Socrates by this time.[1] Further details in Plato's writing point to Phaedrus' interests in mythology and natural science.[3]

On the Mysteries, an extant speech of Andocides, names Phaedrus as one of the individuals indicted by the city of Athens, at the behest of the metic Teucrus, in the profanation of the Eleusinian mysteries,[6] a major domestic event preceding the calamitous Sicilian Expedition in 415. Inscribed records of the property confiscated from the profaners of the mysteries[7] and a speech of Lysias[8] further attest to his role in this event.[1] Phaedrus fled Athens at this time along with the other accused parties, losing his wealth and property in the process. Some scholars had previously interpreted Andocides as naming Phaedrus in his list of mutilators of the Herms,[2] a contemporaneous Athenian scandal, but this is generally dismissed within present scholarship.[1]

Phaedrus married his first cousin, whose name is Pheobe, circa 404. After his early death in 393, his wife remarried Aristophanes, son of Nicophemus.[1]

Depiction in literature and influence

In his eponymous Platonic dialogue, Phaedrus recites a speech attributed to Lysias, while he calls upon several classical myths to construct a tragic account of Eros in the Symposium. His character in Plato, along with the ill-fated implications of his oncoming exile, has long exerted influence on literature and philosophy. Among the ancients, Alexis' mid-late 4th century comedic play Phaedrus depicts a man philosophizing on the nature of eros,[1] while Diogenes Laërtius assumes Phaedrus to be Plato's "favorite" individual.[9] Modern scholars such as Nussbaum and John Sallis have interpreted his character as an embodiment of the fecundity and potential tragedy of philosophical eroticism.[2][3]

References

- Debra Nails, The People of Plato, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2002; pp. 233–234

- Martha Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001; pp. 200–224

- John Sallis, Being and Logos, Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 1997; pp. 104–172

- e.g., Plato, Phaedrus, 228c

- Plato, Protagoras, 315c

- Andocides, On the Mysteries, 1.15

- "IG I3 421 Sale of property confiscated from those condemned for mutilating the Herms and profaning the Mysteries (A)". Attic Inscriptions Online. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- Lysias, 32

- Diogenes Laërtius, 3.29