Peruvian retablo

Retablos are a sophisticated Peruvian folk art in the form of portable boxes which depict religious, historical, or everyday events that are important to the Indigenous people of the highlands. It is a tradition originated in Ayacucho.

The Spanish word retablo comes from the Latin retro-tabulum (“behind the table or altar”), which was later shortened to retabulum. This is a reference to the fact that the first retablos were placed on or behind the altars of Catholic churches in Spain and Latin America. They were three-dimensional statues or images inside a decorated frame.

Origins

The retablos probably originated with the Christian knights of the Crusades and the Spanish reconquista (the 700-year struggle against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula).

The Christian warriors, who frequently found themselves far away from their home churches, carried small portable box-altars for worship and protection against their enemies. These earliest retablos usually featured religious themes, especially those involving Santiago (Saint James), the patron saint-warrior in the fight against the Moors.

Retablos came to the New World as small portable altars, Nativity scenes and other religious topics used by the early priests to evangelize the Indigenous.

Adam and Eve

There is a story of how a Catholic priest effectively used a retablo to hold the attention of his Indigenous audience. He began with a closed retablo, and told a long story about what was in the box, which he kept closed:

- a naked man

- ...a naked woman

- ...a snake

- ...temptation...

- sin...and punishment.

- He eventually opened the box and revealed that he was talking about...the creation of Adam and Eve.

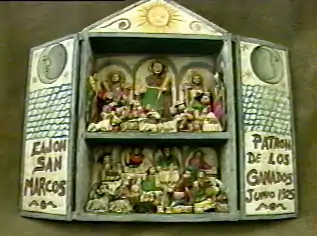

Patron saint of cattle

In a syncretic process, the early retablos brought by the Spanish merged with Indigenous beliefs in the Andean region to acquire certain magical or symbolic properties which had been the attributes of local spirits before the Conquest. This was particularly true of the retablos named after St. Mark, known as cajones sanmarcos (“boxes of St. Mark”). Since St. Mark is the patron saint of farm animals, his spirit was used to invoke protection of cattle from disease and theft. These early retablos were wooden boxes with figures inside carved from stone, ivory or wood.

Daily life and identity

Later, retablos evolved to include daily scenes in the lives of the Andean people, such as harvests, processions, feasts, and tableaux depicting shops and homes.

The use of wood for the outside box remained, but other materials, such as gypsum, clay, or a potato-gypsum-clay paste mix, were increasingly used for the figures because of their ease of handling and durability.

In the 1940s more and more artists were using retablos as a vehicle for affirming and recording the distinct identity of the Indigenous people of the Andean region. They are also a defense of Indigenous culture and values in the face of the modernization and the penetration of their culture by that of the white Hispanic elites of Lima.

Ayacucho and Nicario Jiménez

The tradition of making cajones sanmarcos or retablos is very strong in the mountainous Peruvian region around the city of Ayacucho. In recent years the political violence and the fighting between the Peruvian Army and the Marxist Sendero Luminoso (“Shining Path”) guerrillas around Ayacucho has forced many peasant families in the area to migrate to the capital city of Lima, where they make and sell their crafts commercially.

Nicario Jiménez Quispe (Quispe is his mother’s name) is a master artisan of the craft of making retablos. He was born in 1957 in a small highland Andean village near Ayacucho, and learned how to make retablos from his father and other skilled craftsmen. He has studied at the University of San Marcos in Lima, and has exhibited his retablos in Peru and abroad in several international competitions. His photo was taken while doing a demonstration at American University’s Language and Foreign Studies Department in 1991.

Ayacucho

In 1968 Nicario’s family moved from their small village to the city of Ayacucho. A decade later Nicario Jiménez had his first chance to display his retablos alongside those of his father in a Lima gallery. The quality of and unique style of his work quickly caught the attention of many Peruvian and foreign connoisseurs of retablo folk art. In 1986 he opened his own workshop-gallery in Lima.

His themes

He frequently injects elements that remind us of his Andean heritage. For example, this Crucifix has three coca leaves below the heart of Christ. He says he put them there to remind us that coca leaves (not cocaine) play an important role in Indigenous Andean cultures.

The curandero (shaman)

The shaman, or curandero (healer) practices traditional folk medicine. He uses various herbs, including coca leaves, and passes a live Andean guinea pig (the cuy) over the body or the patient as a diagnostic tool. The cuy is then killed and its entrails studied to diagnose the illness and prescribe treatment, which is a combination of traditional medicinal herbs and Christian practices.

Yawar fiesta

This retablo shows a ceremony (“Yawar Fiesta”) involving a struggle between a bull (symbol of the Spanish) and a condor (symbol of the Andeans). The condor is tied to the back of the bull, who is infuriated and cannot rid itself of the condor, and eventually dies from exhaustion. The condor is then set free. It spreads its wings, and it becomes the symbol of the freedom of the Andean Indigenous peoples.

The Pistaku (cutter of throats)

Pistaku is a Quechua Indigenous word meaning “cutter of throats,” and he is the subject of an oral tradition among the Andean people. The Pistaku attacks and kills solitary travelers in the countryside in order to extract their fat. He is portrayed as a foreigner, and is tall, bearded, wears boots, and generally looks like a European.

The top part of the retablo represents the Colonial period and shows the Pistaku dressed as a Franciscan priest who extracts human fat to make bells whose sound varies according to the victim.

The middle portion shows the modern period when the Pistaku, wearing a cape, is a long-haired gringo who extracts fat to lubricate his airplanes and machines.

The final portion of the retablo is contemporary. The Pistaku appears more violent, especially in the period of former President Alán García. The human fat he extracts now not only serves to lubricate airplanes and machinery, but also to pay the external debt and buy weapons.

Sendero Luminoso (“Shining Path”)

In recent years there have been more controversial retablos, such as those showing exploitation and mistreatment of the Indigenous peoples, and the plight of the Andean people caught between leftist guerrillas and the security forces of the State.

One recurring theme is the way the campesino is caught between the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) Marxist guerrillas and the military.

See also

References

- Craven, Roy C., Jr. “Andean Art: An Endangered Tradition.” Américas, vol. 30, no. 1, January 1978, pp. 41-47.

- Egan, Martha. “The Retablos of Nicario Jiménez.” Artspace (Southwestern Contemporary Arts Quarterly), Summer, 1987, pp. 11-13.

- Jiménez Quispe, Nicario. Cuadernos de Arte y Cultura Popular. Lima: Taller-Galería de Retablos Ayacuchanos, Lima, no. 1, 1990.

- Milliken, Louise. Folk Art of Peru. Washington: The Phillips Collection, 1978.

- Sebastianis Stefania. Erranze plastiche. Antropologia e storia del retablo andino. Roma: Cisu, 2002.

- Sebastianis Stefania. La costruzione dell’indianità. L’arte popolare di Ayacucho dall’indigenismo ai siti web. Udine: Forum Editrice Universitaria Udinese, 2006.

- Sordo, Emma María. Retablos from Ayacucho, a Traditional Popular Art of the Peruvian Andes. University of Florida MA Thesis, 1987.

- Stein, Steve, Popular Art and Social Change in the Retablos of Nicario Jimenez Quispe. Edward Mellen Press, 2005. 3. 3.9.