Perseus (spy)

Perseus (Russian: Персей, romanized: Persey) was the code name of a hypothetical Soviet atomic spy that, if real, would have allegedly breached United States national security by infiltrating Los Alamos National Laboratory during the development of the Manhattan Project, and consequently, would have been instrumental for the Soviets in the development of nuclear weapons.

Among researchers of the subject there is some consensus that Perseus was actually a creation of Soviet intelligence.[1][2] Hypotheses include that "Perseus" was created as a composite of several different spies, disinformation to distract from specific spies, or may have been invented by the KGB to promote itself to the Soviet leadership to obtain more state funding.

There were, however, multiple confirmed Soviet spies on the Manhattan project. They included Theodore Hall, George Koval, Morton Sobell, David Greenglass, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Klaus Fuchs, and Harry Gold.[3]

Character and history

A reference to the profile of a spy who can be identified with Perseus describes them as an American scientist of young age at the time of the Manhattan Project.[4][5]

If they were real, Perseus would have supposedly been of age to participate in the Spanish Civil War.[6][7]

In the early 1940s Perseus would have been in New York City visiting his sick parents.[7] During his stay in that city, they would have managed to be recruited by the GRU after looking for and contacting Morris Cohen,[8] an American who joined the Communist Party during the Great Depression[5] and worked as a Soviet spy.[9]

The meeting with Cohen must have been between September 1941 and July 1942, before Cohen enlisted in the army and left for the Western Front in Europe.[8]

Perseus reportedly introduced themself to Cohen as a physicist who had been invited to join the work at Los Alamos research center. By 1942, Perseus was supposedly already working at Los Alamos, being that they would have started sometime at least 18 months before German physicist and fellow atomic spy Klaus Fuchs, who joined the Manhattan Project in mid-1944. However, Perseus appears to have been recruited by the Soviets around the same (or at least a nearby) time as Fuchs.[8]

According to articles published in Russia by The New Times, Perseus would have collaborated with the Soviet government for purely ideological reasons to the point that they refused any financial rewards in exchange for classified information, since they were convinced that the United States would use the atomic bomb against the Soviet Union, allegedly claiming that:

"The Pentagon is of the opinion [...] that it will take the Soviet Union decades to harness atomic energy. In the meantime, America will destroy socialism by means of the uranium bomb."[8]

With Morris Cohen in Europe, his wife, Lona Cohen, took it upon herself to travel to Albuquerque on one or two occasions (depending on the source consulted) to serve as a carrier.

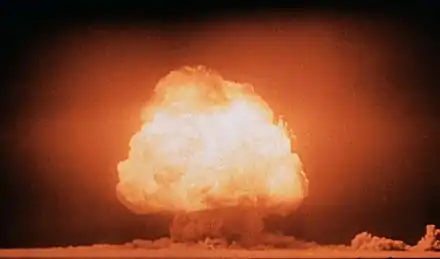

Once there, Lona Cohen would have received information allegedly directly from Perseus, and took it to the Soviet consul in New York City, Anatoli Yatskov. This information allegedly included crucial details about the Trinity Test, which was detonated in July 1945.[8]

In the 1950s, Perseus was supposedly under the control of Rudolf Abel.[10]

According to one source, Perseus was supposedly still alive in 1991.[8]

Perseus was also allegedly referred by or identified with the code names of «Mr. X»,[8] «Youngster»,[11] FOGEL,[12] PERS[11][12][13] and «Mlad».[11][14]

This name is also given to a spy at White Sands Missile Range, located further south near Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Alleged confirmations of existence

Vladimir Chikov

In April 1991, KGB colonel and public relations officer Vladimir Chikov published articles in the Russian weekly "The New Times" in which he commented on the existence of a Russian spy who worked in the Manhattan Project under the code name of Perseus, giving details of his recruitment and achievements.[8]

Regarding the information published by Chikov in The New Times, an article in The Washington Post comments:

"There are some contradictions and inconsistencies in Chikov's version of how Perseus was recruited, which make his New Times article a somewhat unreliable source. But unless the Russian intelligence agency is playing a gigantic hoax, there seems little doubt that the Kremlin had such an agent. The latest batch of intelligence documents contains information that could only have come from a scientist with direct access to the innermost secrets of the Manhattan Project."[8]

Anatoli Yatskov

In an interview published in 1992, the former Soviet consul in New York, Anatoli Yatskov, confirmed the existence of Perseus,[8] as an important figure among scientists working on the Manhattan Project.[15]

During his tenure as consul, Yatskov used the pseudonym Anatoly Yakovlev and served as a Soviet intelligence agent, coordinating atomic spies in the United States.[8]

Yatskov gave details about Perseus' recruitment, how he sent information from New Mexico to New York (through Morris Cohen's wife), and confirmed that the Soviet Union received information from both Klaus Fuchs and Perseus.[8]

Morris Cohen and Lona Cohen

In an interview given before his death in 1995, the American-born Soviet spy Morris Cohen confirmed that in addition to Klaus Fuchs, there was a second physicist in the Manhattan Project who worked as a Soviet spy.[4]

The details in Cohen's story coincide with the statements of Colonel Vladimir Chikov a few years earlier, such as the recruitment of people close to the Manhattan Project as spies, the existence (suspected by American intelligence) of an unidentified scientist who collaborated with Soviet intelligence, and the interaction of said scientist with Lona Cohen (Morris Cohen's wife) to transport stolen information.[5]

According to Cohen, by the fall of 1994 there were very few people left in Soviet intelligence ("two or maybe three") who knew the real name of the second spy scientist.[4]

For her part, shortly before her death in 1992, Lona Cohen had a telephone interview with historian Walter Schneir. In that interview, Lona Cohen confirmed that she had made at least one trip between Albuquerque and New York to transport classified information stolen from the United States, but she could not quite remember who she had interviewed with in New Mexico, saying that it was probably a scientist or physicist.[8]

References in the Venona project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program run by the Signal Intelligence Service that (later became part of the National Security Agency,) started in the Second World War and was active since February 1943 to October 1980.[16]

The objective of the program was to intercept and decrypt messages from diplomats, intelligence agencies (such as the NKVD and the KGB), business representatives and other actors of the Soviet government.[17]

Despite the fact that only a fraction of the messages intercepted by Venona were suitable for decryption,[18] the project left an archive of around 3000 decrypted and translated messages.[19]

Although there is no mention of Perseus in the Venona files, there are references to a spy under the code name PERS[13] or FOGEL.[12] Apparently, at some point the codename PERS was turned into Perseus by mistake.[12]

PERS was identified in the Venona files as part of the group of four Soviet spies (of which only 3 had been identified) who infiltrated the Manhattan Project.[12]

Despite the fact that by 2012 a publication by NSA's Center for Cryptologic History described PERS as "important, but still unidentified",[13] the references in the Venona files have been questioned[11] or even used to confirm that Perseus never existed.[14]

In 2009, VOGEL/PERS was outed as being actually Russell A. McNutt, a civil engineer employed by the company Kellex to work on facilities at Oak Ridge, who was recruited as a spy by Julius Rosenberg.[20]

4th spy at Los Alamos

From the early 1950s till 1995, three Soviet spies had been confirmed to have infiltrated Los Alamos: Klaus Fuchs (German physicist), David Greenglass (military man and brother-in-law of Julius Rosenberg) and Theodore Hall (American physicist).[14]

Fuchs voluntarily confessed to British MI5 authorities in January 1950[21] and this subsequently lead to Greenglass in June of that same year.[22] Finally, Hall's involvement was not identified until the release of documents from Venona in 1995,[14] a few years before his death in 1999.[23]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, publications like those by Chikov and Yatskov strengthened the theory of a possible fourth spy in Los Alamos, who would have been identified as Perseus (the PERS in the Venona files) or FOGEL.[12]

Alleged rebuttals of existence

Pavel Sudoplatov

In 1994 the lieutenant general and Soviet agent Pavel Sudoplatov published a book titled Special Tasks.[24]

In the book, Sudoplatov referred to the statements made by Anatoly Yatskov, and stated that he did not remember that code name and, that in his opinion, it could be that Yatskov or his associates created Perseus to cover the true identities of Soviet informants.[24]

However, Sudoplatov also acknowledged that the codename Perseus was used to refer to or cover a number of agents and anonymous sources.[25]

Sudoplatov misidentified Bruno Pontecorvo as the spy codenamed "Mlad", who is now identified as Ted Hall by researchers.[26]

John Earl Haynes

United States Cold War historian John Earl Haynes concluded that Perseus was an invention,[11] relying on the research of authors Joseph Albright, Marcia Kunstel and Gary Kern.[14]

In an index of false names, pseudonyms, and real names of spies, Haynes notes under the Perseus entry that:

"“Perseus" also "Mlad"/"Youngster" aka Arthur Fielding: unidentified Soviet source, American physicist in the Manhattan Project. Likely a faked composite by Vladimir Chikov and the SVR combining part of the story of Theodore Hall with misdirection and distortion."[11]

However, Haynes acknowledges that although Perseus was an invention, there must have been a 4th Soviet spy operating in Los Alamos during the development of the Manhattan Project in addition to the 3 spies identified until 1995: Klaus Fuchs, David Greenglass and Theodore Hall.[14]

Albright and Kunstel

In their book Bombshell: The Secret Story of America's Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy, authors Joseph Albright and Marcia Kunstel dedicate the twentieth chapter to Perseus under the title of "The Perseus Myth" in which they conclude that the spy never existed.[2]

According to the authors, the KGB may have created Perseus for the purposes of self-promotion, to justify its own existence, and even to secure more state funding.[2]

Gary Kern

In 2006 mail that was made public, author Gary Kern explained why he believed Perseus was an invention. Kern believes that Perseus was an extremely risky disinformation operation with multiple objectives, including:[27]

- Show that the KGB was vital for the Soviet Union and, after 1991, for Russia.

- Prove that the KGB dominated the field (intelligence and espionage) better than the American and British agencies, since the latters were never able to catch the hypothetical Russian agent.

- Give more credit and prestige to Soviet intelligence agents for the development of nuclear weapons, even if this meant diminishing the contribution of Soviet scientists.

- Use Soviet spies of foreign origin living in Russia for propaganda, particularly the Cohens.

- Have some financial gain with the possible sale of the story.

Alleged identities

.jpg.webp)

Philip Morrison

In April 1999 American scientist, activist, and president of the Federation of American Scientists from 1970 to 2000, Jeremy Stone, published his memoirs under the title Every Man Should Try: Adventures of a Public Interest Activist.[7]

Motivated by an article in The Washington Post about Vladimir Chikov's publications in Russia,[24] Stone decided to take on the subject, and in his book he disclosed conversations and visits he had with someone he knew personally and only identified with the pseudonym "Scientist X" (or "Dr. X" [24][28]), and explained why he believed that this "Scientist X" was the real Perseus.[7]

Despite the use of a pseudonym, thanks to the information in the book, the "Scientist X" was easily identified as Philip Morrison, a physicist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[7]

Morrison denied the accusation and gave a solid rebuttal against it,[6][29] noting that:

- According to Chikov, Perseus participated in the Spanish Civil War, but during this time (1936–1939), Morrison was studying or about to graduate from Berkeley.[6] Also, during his childhood, Morrison contracted polio, which affected his legs to the point that he required a cane to walk, making it unlikely that he could fight in a war.[7]

- According to another source, Perseus would have been in New York City between 1941 and 1942 visiting his parents, but at the time Morrison's parents resided in Philadelphia[7] and his family lived in Pittsburgh.[6]

Other reasons that led Stone to suspect Morrison were questioned, namely:[7]

- Stone thought that the ideas expressed in a phrase attributed to Perseus were similar to ideas expressed by Morrison (although Stone accepted that, had Perseus existed, his phrases would have been in English, to later be translated into Russian (in publications such as Chikov's) and then translated back into English by US media).

- During a 1994 conversation between the two, Stone was already suspicious of Morrison, so he brought up the subject of Perseus indirectly and Morrison's reaction (according to Stone) was so nervous that his knees trembled, but this could be explained by the aftermath of the polio that Morrison suffered in his childhood.

To all of the above, Stone accepted Morrison's rebuttal, stating that: "In the light of these facts, which I certainly cannot contradict, [...] I can only accept your denial that you are Perseus."[28]

Finally, thanks to the controversy raised by the event, several academics and people close to the Federation of American Scientists expressed their wishes for Stone to apologize, and even expressed the idea of calling Stone to present his resignation as head of the Federation.[7]

Oscar Seborer

According to historian John Earl Haynes and academic Harvey Klehr, thanks to FBI documents that were declassified in the 2010s, they were able to confirm the existence of a suspected fourth spy who they identified as Oscar Seborer.[14]

Seborer was an American engineer who was drafted into the United States Army in 1942[30] and, like all his siblings, had sympathy for the Communist Party USA.[31]

Given his education as an engineer, Seborer was assigned to the Special Engineer Detachment,[30] a program that identified members of the army with specific skills or technical training, and funneled them to the Manhattan Project.[32][33]

However, Haynes and Klehr are emphatic that Seborer should not be identified with Perseus, since while Perseus would have been an invention probably based on Theodore Hall, Seborer's life and profile have no relation to the characteristics attributed to Perseus.[14]

Theodore Hall

According to historian John Earl Haynes and academic Harvey Klehr, although Perseus never really existed,[14] some aspects of his character were based on or coincide with the American Soviet spy and physicist Theodore Hall.[11] These aspects include:

- Age: Hall was the youngest scientist working on the Manhattan Project,[23] while the possible reference by Morris Cohen defines Perseus as young[4] and another codename attributed to Perseus is "Youngster".[11]

- Parents' residence: According to Vladimir Chikov, Perseus would have sought to be recruited by the GRU in New York City, after a visit to his parents.[7] Hall's parents lived in New York City, and were coincidentally visited by Hall about the same time.[6]

- Attributed code names: According to Haynes and Klehr, the use of the code name "Mlad" has been wrongly attributed to Perseus, but it actually identified Hall.[14] Likewise, the code name "Youngster" has been attributed to both Hall[11] and Perseus.[12]

- Lifespan: According to Vladimir Chikov, Perseus was still alive in 1991;[8] Hall did not pass away until 1999[23] and his identity as a spy was not exposed until 1995.[14]

Born in New York City, Hall was an American physicist who was considered a prodigy from an early age, and graduated from Harvard University at 18. Concerned about the advance of fascism at the time, Hall developed sympathies for socialism.[34]

Although Haynes and Klehr noted that the agent identified as Perseus (or sometimes as "Mlad") has attributes and characteristics that do not match Hall, they still concluded that Perseus must have actually been an invention, the result of a misinformation operation with the goal of protecting Hall, who was still alive in the early 1990s.[14] This could explain the presence of attributes that coincide between both at the same time of others that do not.

In popular culture

On August 19, 2020, Perseus was first referenced in the worldwide teaser trailer for Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War.[35][36][37] He was later confirmed as the main antagonist in the game's campaign which is set in both the 1980s and the Vietnam War.[38] In the game, Perseus is an international spy ring made up of espionage agents and rogue operators, with connections to a great number of anti-Western groups. The group is supposedly headed by a Soviet intelligence officer under the codename "Perseus". Perseus loosely appears during the game's campaign and is featured in the final scenes of the Pro-Soviet ending as the one responsible for taking control of the fictional Operation Greenlight, which saw the insertion of nuclear weapons in every major European city, as an ultimate countermeasure to a Soviet invasion. The character referred to as "Perseus" is voice acted by American actor William Salyers.[39]

See also

Bibliography

- Albright, Joseph; Kunstel, Marcia (1997). "The Perseus Myth". In Times Books (ed.). Bombshell: The Secret Story of America's Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy (First ed.) (published September 16, 1997). ISBN 978-0812928617. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Benson, Robert L. (August 7, 2012). The Venona Story (PDF). Fort George G. Meade, Maryland: Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Goodman, Michael (July 2005). "Who Is Trying to Keep What Secret From Whom and Why? MI5-FBI Relations and the Klaus Fuchs Case". Journal of Cold War Studies. 7 (3): 124–146. doi:10.1162/1520397054377160. ISSN 1531-3298. S2CID 57560118. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Jones, Vincent C. (1985) [1985]. Elsberg, John W. (ed.). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb (PDF) (First ed.). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Klehr, Harvey; Haynes, John Earl (September 2019). Central Intelligence Agency (ed.). "On the Trail of a Fourth Soviet Spy at Los Alamos" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. 63 (3): 1–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Rhodes, Richard (1 August 1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-68-480400-2. LCCN 95011070. OCLC 456652278. OL 7720934M. Wikidata Q105755363 – via Internet Archive.

- Rothstein, Linda (July 4, 1999). "Nuclear Secrets: The Perseus Papers" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 5 (4): 17–19. doi:10.2968/055004006. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Sagdeev, Roald (May 1993). "Russian scientist save American secrets" (Google Books). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 49 (4): 32–36. Bibcode:1993BuAtS..49d..32S. doi:10.1080/00963402.1993.11456342. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

References

- Klehr & Haynes 2019, p. 1,13.

- Albright & Kunstel 1997, p. 267–277.

- "Espionage". Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- "Morris Cohen; stole U.S. Atoms secrets for Soviets". Chicago Tribune. Cox Media Group. June 28, 1995. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

I think that two or maybe three people remain in the Russian Intelligence Service who know his real name.

- "American spy for Soviets dies with secret". The Baltimore Sun. Cox Media Group. June 28, 1995. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Rothstein 1999, p. 19.

- Chandler, David L. (June 14, 1999). "Friendship lost in 'Perseus' quest; Espionage: A respected activist's charges that a Manhattan Project scientist shared U.S. nuclear secrets with the Soviets has created a rift between them". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Dobbs, Michael (October 4, 1992). "How Soviets stole U.S. Atoms Secrets". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Editorial Staff (July 5, 1995). "Soviet Spyes Morris Cohen dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Egorov, Boris (August 21, 2020). "Who is the mysterious Soviet spy 'Perseus' from the new Call of Duty game?". www.rbth.com. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Haynes, John Earl (April 2009). "Cover Name, Cryptonym, Pseudonym, and Real Name Index. A Research Historian's Working Reference. Compiled by John Earl Haynes". www.johnearlhaynes.org/. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

"Perseus" also "Mlad"/"Youngster" [...] Likely a faked composite by Vladimir Chikov and the SVR combining part of the story of Theodore Hall with misdirection and distortion.

- "Venona: Soviet Espionage and the American Response, 1939–1957. Preface". Central Intelligence Agency. March 19, 2007. Archived from the original on November 1, 2006. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

The four assets apparently were Klaus Fuchs (covernames CHARLES and REST), David Greenglass (covernames BUMBLEBEE and CALIBRE), Theodore Alvin Hall (covername YOUNGSTER [MLAD]), and a source covernamed FOGEL and PERS; see New York 1749–50 to Moscow, 13 December 1944, Translation 76. PERS seems to have been arbitrarily or erroneously converted to "Perseus" (there is no covername Perseus in the Venona messages) in Russian memoirs as the Soviet and Russian intelligence services sought to describe a high-level source in the Manhattan Project. For more on Russian claims for Perseus, see Chikov, "How the Soviet intelligence service `split' the American atom," (Part 1), p. 38.

- Benson 2012, p. 18.

- Klehr & Haynes 2019, p. 1.

- Sagdeev 1993, p. 35.

- Benson 2012, p. 7-8.

- Benson 2012, p. 5.

- Benson 2012, p. 15.

- Benson 2012, p. 14.

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey; Vassiliev, Alexander (2009). Yale University Press (ed.). Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. pp. 34–39..

- Goodman 2005, pp. 130–131.

- Rhodes 1995, pp. 428–30.

- Cowell, Alan S. (November 10, 1999). "Theodore Hall, Prodigy and Atomic Spy, Dies at 74". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

Theodore Alvin Hall, who was the youngest physicist to work on the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos during World War II and was later identified as a Soviet spy, died on Nov. 1 in Cambridge, England, where he had become a respected, if not a truly leading, pioneer in biological research. He was 74.

- Rothstein 1999, p. 18.

- Schecter, Jerrold L. (May 2, 1994). "In Defense of Gen. Sudoplatov's Story". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Albright & Kunstel 1997, p. 276.

- Gary, Kern (February 17, 2006). "The PERSEUS Disinformation Operation (Kern)". lists.h-net.org/ (Mailing list). Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Accuser in Spy Case Accepts a Denial". The New York Times. May 14, 1999. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

In the light of these facts, which I certainly cannot contradict, Mr. Stone wrote in response on Tuesday, I can only accept your denial that you are Perseus.

- Goodwin, Irwin (July 1999). "New Book Unmasks Scientist X as Spy, But Facts of Case Tell a Different Story". Physics Today. 52 (7): 39–40. Bibcode:1999PhT....52g..39G. doi:10.1063/1.882748. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Klehr & Haynes 2019, p. 5.

- Klehr & Haynes 2019, p. 4.

- Jones 1985, p. 349.

- Jones 1985, p. 497.

- Curley, Robert (ed.). "Theodore Hall. American-born physicist and spy". www.britannica.com (Encyclopedia article.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- Parrish, Ash (August 19, 2020). "Call of Duty: Black Ops: Cold War Is The Next Call Of Duty". kotaku.com. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Hollister, Sean (August 19, 2020). "Call of Duty Black Ops: Cold War is official, will be 'inspired by actual events'". www.theverge.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Onder, Cade (August 19, 2020). "Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War officially revealed". GameZone. Archived from the original on August 30, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- Higham, Michael (August 27, 2020). "Call Of Duty: Black Ops Cold War Revealed: A Direct Sequel To Black Ops 1". www.gamespot.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War". IMDb. November 13, 2020.