Penobscot Expedition

The Penobscot Expedition was a 44-ship American naval armada during the Revolutionary War assembled by the Provincial Congress of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The flotilla of 19 warships and 25 support vessels sailed from Boston on July 19, 1779, for the upper Penobscot Bay in the District of Maine carrying an expeditionary force of more than 1,000 American colonial marines (not to be confused with the Continental Marines) and militiamen. Also included was a 100-man artillery detachment under the command of Lt. Colonel Paul Revere.

| Penobscot Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Destruction of the American Fleet at Penobscot Bay, 14 August 1779, Dominic Serres | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

700[1] 10 warships[2] |

3,000 19 warships[2] 25 support ships[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 86 killed, wounded, captured or missing[3][4] |

474 killed, wounded, captured or missing 19 warships sunk, destroyed or captured 25 support ships sunk, destroyed or captured[5] | ||||||

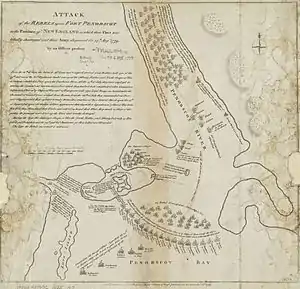

The expedition's goal was to reclaim control of mid-coast Maine from the British who had captured it a month earlier and renamed it New Ireland. It was the largest American naval expedition of the war. The fighting took place on land and at sea around the mouth of the Penobscot and Bagaduce rivers at Castine, Maine, over a period of three weeks in July and August. It resulted in the United States' worst naval defeat until Pearl Harbor 162 years later in 1941.[6]

On June 17, British Army forces landed under the command of General Francis McLean and began to establish a series of fortifications around Fort George on the Majabigwaduce Peninsula in the upper Penobscot Bay, with the goals of establishing a military presence on that part of the coast and establishing the colony of New Ireland. In response, the Province of Massachusetts raised an expedition to drive them out, with some support from the Continental Congress.

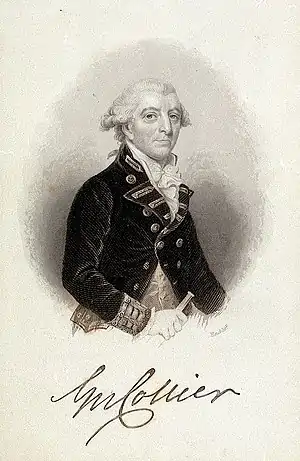

The Americans landed troops in late July and attempted to besiege Fort George in actions that were seriously hampered by disagreements over control of the expedition between land forces commander Brigadier General Solomon Lovell and expedition commander Commodore Dudley Saltonstall, who was later dismissed from the Navy for ineptitude. For almost three weeks, General McLean held off the assault until a British relief fleet arrived from New York on August 13 under the command of Sir George Collier, driving the American fleet to destruction up the Penobscot River. The survivors of the expedition made an overland journey back to more populated parts of Massachusetts with minimal food and arms.

Background

British war planners looked for ways to gain control over the New England colonies following the somewhat successful raid on Machias in 1777 and General John Burgoyne's failed Saratoga campaign, but most of their effort was directed at another campaign against the southern colonies. Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord George Germain and his Under-Secretary William Knox were responsible for the war effort, and they wanted to establish a base on the coast of the District of Maine that could be used to protect Nova Scotia's shipping and communities from American privateers and raiders.[7][8] The British also hoped to keep open the timber supply of the Maine coast for masts and spars for the Royal Navy. The coast down to the Penobscot was also next to the Bay of Fundy, which was easily approached from the large British naval base at Halifax. Loyalist refugees in Castine had also proposed establishing a new colony or province to be called New Ireland as a precursor to New Brunswick.[9][10] Sir Francis Bernard supported the idea of a new colony, as it would make "a resort for the persecuted loyalists of New England".[11]

John Nutting was a Loyalist who had piloted Sir George Collier's expedition against Machias, and Knox induced him to write to Germain in January 1778 to promote the idea of a British military presence in Maine; he later dispatched him to London to do so in person. Nutting described the Castine peninsula as having a harbor that "could hold the entire British Navy" and was so easily defensible that "1,000 men and two ships" could protect it against any Continental force. He also proposed that the strategic location of such a post would help to carry the war to New England and would offer protection for Nova Scotia.[12] Germain drafted orders for Lieutenant General Henry Clinton on September 2, to establish "a province between the Penobscot and St. Croix rivers. Post to be taken on Penobscot River".[13]

Germain ordered Clinton to "send such a detachment of troops at Nova Scotia, or of the provincials under your immediate command, as you shall judge proper and sufficient to defend themselves against any attempt the rebels in those parts may be able to make during the winter to take post on Penobscot River, taking with them all necessary implements for erecting a fort, together with such ordnance and stores as may be proper for its defense, and a sufficient supply of provisions."[14] However, Nutting's ship was captured by an American privateer and he was forced to dump his dispatches, bringing an end to the idea of a new colony in 1778.[13]

Order of battle

Royal Navy

- British Squadron, commanded by George Collier[15]

- HMS Raisonnable (64 guns)

- HMS Greyhound (32 guns)

- HMS Blonde (32 guns)

- HMS Virginia (32 guns)

- HMS Galatea (20 guns)

- HMS Camilla (20 guns)

- HMS Nautilus (18 guns)

- HMS Otter (14 guns)

- HMS Albany (14 guns)

- HMS North (14 guns)

Continental Navy

- 1st Squadron, commanded by Solomon Lovell[15]

- Warren (32 guns)

- Vengeance (24 guns)

- Charming Sally (22 guns) (privateer)[16]

- Black Prince (18 guns) (privateer)[17]

- Hunter (18 guns)

- Active (16 guns)

- Hazard (16 guns)

- Tyrannicide (14 guns)

- Springbird (12 guns) (privateer)[18]

- Rover (10 guns) (privateer)[19]

- 2nd Squadron, commanded by Dudley Saltonstall[15]

- Monmouth (24 guns)

- Putnam (24 guns)

- Hector (20 guns)

- Hampden (20 guns) (privateer)[20]

- Sky Rocket (16 guns)

- Defense (16 guns) (privateer)[21]

- Nancy (16 guns) (privateer)[22]

- Diligence (14 guns)

- Providence (14 guns)

British forces arrive

Nutting reached New York in January 1779, but General Clinton had received copies of the orders from other messengers. Clinton had already assigned the expedition to General Francis McLean who was based in Halifax, and he sent Nutting there with Germain's detailed instructions.[23]

McLean's expedition set sail from Halifax on May 30, and arrived in the Penobscot Bay on June 12. The next day, McLean and Captain Andrew Barkley, the commander of the naval convoy, identified a suitable site at which they could establish a post.[24] On June 16, his forces began landing on a peninsula that was called Majabigwaduce (Castine, Maine) between the mouth of the Bagaduce River and a finger of the bay leading to the Penobscot River.[6] The troops numbered approximately 700, consisting of 50 men of the Royal Artillery and Engineers, 450 of the 74th Regiment of (Highland) Foot, and 200 of the 82nd (Duke of Hamilton's) Regiment.[1] They began to build a fortification on the peninsula which jutted into the bay and commanded the principal passage into the inner harbor.

Fort George was established in the center of the small peninsula, with two batteries outside the fort to provide cover for Albany, which was the only ship expected to stay in the area. A third battery was constructed on an island south of the bay near the mouth of the Bagaduce River, in which Albany was harbored. Construction of the works occupied the troops for the next month, until rumors came that an American expedition was being raised in Boston to oppose them,[25] following which efforts were redoubled to prepare works suitable for defense against the Americans.[26] Captain Henry Mowat of the Albany was familiar with Massachusetts politics, and he took the rumors quite seriously and convinced General McLean to leave additional ships that had been part of the initial convoy. Some of the convoy ships had already left, but the orders were countermanded before armed sloops North and Nautilus were able to leave.[27]

American reaction

When news reached the American authorities at Boston, they hurriedly made plans to drive the British from the area. The Penobscot River was the gateway to lands controlled by the Penobscot Indians who generally favored the British, and Congress feared that they would lose any chance of enlisting the Penobscots as allies if a fort were successfully constructed at the mouth of the river. Massachusetts was also motivated by the fear of losing their claim over the territory in any post-war settlement.[28]

To spearhead the expedition, Massachusetts petitioned Congress for the use of three Continental Navy warships: the 12-gun sloop Providence, 14-gun brig Diligent, and 32-gun frigate Warren. The rest of more than 40 vessels were made up of ships of the Massachusetts State Navy and private vessels under the command of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall.[N 1] The Massachusetts authorities mobilized more than 1,000 militia, acquired six small field cannons, and placed Brigadier General Solomon Lovell in command of the land forces. The expedition departed from Boston harbor on July 19 and arrived off Penobscot on the afternoon of July 25.[29]

Landing

On July 25, nine of the larger vessels in the American flotilla exchanged fire with the Royal Navy ships from 15:30 to 19:00. While this was going on, seven American boats approached the shore for a landing, but turned back when British fire killed a soldier in one of the boats.[30]

On July 26, Lovell sent a force of Continental Marines to capture the British battery on Nautilus Island (also known as Banks Island),[31] while the militia were to land at Bagaduce. The marines achieved their objective, but the militia turned back when British cannon overturned the leading boat, killing Major Daniel Littlefield and two of his men.[32] Meanwhile, 750 men landed under Lovell's command and began construction of siege works under constant fire. On July 27, the American artillery bombarded the British fleet for three hours, wounding four men aboard HMS Albany.[33]

Assault

On July 28, under heavy covering fire from the Tyrannicide, Hunter, and Sky Rocket, Brigadier General Peleg Wadsworth led an assault force of 400 (200 marines and 200 militia)[34] ashore before dawn at Dyce's Head on the western tip of the peninsula with orders to capture Fort George. They landed on the narrow beach and advanced up the steep bluff leading to the fort. The British pickets, who included Lieutenant John Moore, put up a determined resistance but received no reinforcement from the fort and were forced to retire, leaving the Americans in possession of the heights. Eight British troops were captured.[4] At this point, Lovell ordered the attackers to halt and entrench where they were. Instead of assaulting the fort, Lovell had decided to build a battery within "a hundred rods" of the British lines and bombard them into surrender.[35] The American casualties in the assault had been severe: "one hundred out of four hundred men on the shore and bank",[36] with the Continental Marines suffering more heavily than the militia. Commodore Saltonstall was so appalled by the losses incurred by his marines that he refused to land any more and even threatened to recall those already on shore.[34] In addition his flagship, the Continental frigate Warren, suffered considerable damage during the engagement with hits to the warship's mainmast, forestay and gammoning.[37]

Although possessing significant naval superiority over the British, over the next two weeks the excessively cautious Saltonstall dawdled despite repeated requests by General Lovell that he attack Mowatt's position at the entrance to the harbor. Instead he largely maneuvered the American fleet around the mouth of the Penobscot River beyond the range of the British guns with only occasional ineffective attempts to engage the British. As long as the British warships continued to hold the harbor they were able to pin down the American forces on the ground with concentrated fire and prevent them from taking Fort George.[38]

Realizing that time was running out, on August 11 General Lovell again wrote to Saltonstall pleading for him to attack saying: "I mean not to determine on your mode of attack; but it appears to me so very practicable, that any farther delay must be infamous; and I have it this moment by a deserter from one of their ships, that the moment you enter the harbour they will destroy them."[39] Saltonstall's ineptitude at Penobscot would lead to his being dismissed from the Navy as being "ever after incompetent to hold a government office or state post" the following October by the "Committee for Enquiring into the Failure of the Penobscot Expedition" of the Massachusetts General Court which determined that failure of the expedition was primarily the result of the "want of proper Spirit and Energy on the part of the Commodore", that he "discouraged any Enterprizes or offensive Measures on the part of our Fleet", and that the destruction of the fleet was occasioned "principally by the Commodore's not exerting himself at all at the time of the Retreat in opposing the Enemies' foremost Ships in pursuit".[40][41]

Siege

On July 29, one American was killed.[43] July 30, both sides cannonaded each other all day,[44] and on July 31 two American sailors belonging to the Active were wounded by a shell.[43] Lovell ordered a night assault on August 1 against the Half-Moon Battery next to Fort George, whose guns posed a danger to American shipping, and the Americans opened fire at 02:00. Colonel Samuel McCobb's center column, comprising his own Lincoln County Regiment, broke and fled as soon as the British returned fire. The left column comprising Captain Thomas Carnes and a detachment of marines, and the right column comprising sailors from the fleet, kept going and stormed the battery. As dawn broke, the Fort's guns opened up on the captured battery and a detachment of redcoats charged out and recaptured the Half-Moon, routing the Americans and taking 18 prisoners with them. Their own casualties were four men missing (who were killed), and 12 wounded.[45]

The siege continued with minor skirmishing on August 2 with militiaman Wheeler Riggs of Falmouth being killed by an enemy cannon shot that bounced off a tree before hitting him.[43] On August 4, Surgeon John Calef recorded in his journal that several men were wounded in exchanges of fire.[46] On August 5, one man was killed and another captured,[43] and on August 7, 100 Americans engaged 80 British with one killed and one wounded on the American side and two wounded among the British.[47]

During this time, the British had been able to send word of their condition, and request reinforcements, and on August 3 Captain (later Vice Admiral) Sir George Collier led a fleet of ten warships out of New York.[48]

The next day, Saltonstall launched a naval attack against the British fort, but Collier's British relief fleet arrived and attacked the American ships. The privateer Hampden and one other vessel were captured by frigates HMS Blonde and HMS Virginia.[49][50] Over the next two days, the American fleet fled upstream on the Penobscot River pursued by Collier. On August 13, an American officer was wounded by enemy fire.[43] On August 14 and 16 all of the vessels were scuttled and burned by their own crews while the rest were destroyed at Bangor. Several transports were either captured or later salvaged by the British.[51][52] The surviving crews then fled overland to Boston with almost no food or ammunition.

Casualties

Over the course of the siege, Colonel David Stewart claims the British garrison suffered 25 killed and 34 wounded.[3] Stewart gives no figures for captured or missing, but 26 prisoners are known to have been taken by the Americans.[4]

Apart from the 100 men killed and wounded during the assault of July 28, the known American casualties throughout the siege came to 12 killed, 16 wounded and one captured, in addition to "several wounded" on August 4. The History of Penobscot says that "our whole loss of men was probably not less than 150".[53] The chaotic retreat however, brought the American loss up to 474 killed, wounded, captured or missing.[5]

Aftermath

A committee of inquiry blamed the American failure on poor coordination between land and sea forces and on Commodore Saltonstall's failure to engage the British naval forces. On September 7, a Warrant for Court Martial was issued by the Navy Board, Eastern Department, against Saltonstall.[N 2] Upon trial he was declared to be primarily responsible for the debacle, found guilty, and dismissed from military service. Paul Revere, who commanded the artillery in the expedition, was accused of disobedience and cowardice. This resulted in his dismissal from the militia, even though he was later cleared of the charges. Peleg Wadsworth, who mitigated the damage by organizing a retreat, was not charged in the court martial.

Historian George Buker suggests that Saltonstall may have been unfairly blamed for the defeat.[54] Buker argues that Saltonstall was unfairly represented by Lovell and others, and that Saltonstall was a scapegoat for the campaign's failure despite his tactically correct decisions given the geographic and military conditions in Penobscot Bay.

A year later the British Cabinet formally approved the New Ireland project on August 10, 1780, and King George III gave his assent the following day to the proposal to separate "the country lying to the northeast of the Piscataway [Piscataqua] River" from the province of Massachusetts Bay in order to establish "so much of it as lies between the Sawkno [Saco] River and the St. Croix, which is the southeast [sic] boundary of Nova Scotia into a new province, which from its situation between the New England province and Nova Scotia, may with great propriety be called New Ireland".[55] Pursuant to the terms of the 1783 Peace of Paris all British forces then evacuated Fort George (followed by some 600 Loyalists who removed from the area to St. Andrews on Passamaquoddy Bay) and abandoned their attempts to establish New Ireland.[56] During the War of 1812, however, British forces again occupied Fort George (still calling the area New Ireland) from September 1814 to April 1815 and used it as a naval base before withdrawing again with the arrival of peace.[57][58][59] Full ownership of present-day Maine (principally the northeastern borders with New Brunswick) remained disputed until the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842. The "District of Maine" was a part of Massachusetts until 1820 when it was admitted into the Union as the 23rd state as part of the Missouri Compromise.

Legacy

In 1972 the Maine Maritime Academy and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology searched for and found the wreck of Defence, a privateer that was part of the American fleet.[60] Evidence of scuttled ships was also found under the Joshua Chamberlain Bridge in Bangor and under the Bangor town dock, and several artifacts were recovered. Cannonballs were also reported to have been recovered during the construction of the concrete casements for the I-395 bridge in 1986.

The earthworks of Fort George stand at the mouth of the Penobscot River in Castine, accompanied by concrete work added later by the Americans in the 19th century. Archaeological evidence of the expedition, including cannonballs and cannon, was located during an archaeological project in 2000–2001.

Since 2004 a comprehensive exhibit on the Penobscot Expedition has been provided by the Castine Historical Society, located at its base on School Street, Castine.[61]

In 2021, San Francisco Unified School District announced that it would strip Paul Revere's name from Paul Revere K-8 for his role in the Penobscot Expedition. The San Francisco Board of Education mistakenly believed the expedition was to steal land from the Penobscot people.[62]

In popular culture

Bernard Cornwell's 2010 historical novel The Fort gives an account of the expedition. It draws attention to the presence there of a junior British officer named John Moore, later a famous general.

References

- Buker, p. 11

- Campbell, p. 498

- Stewart, p. 115

- Buker, p. 176, note 67

- Boatner, p. 852

- Bicheno, p.149

- Alden, John R. A History of the American Revolution New York: Alfred A Knopf Inc. 1960, pp. 217-18

- Buker, pp. 4–5

- Sloan, Robert W. New Ireland: Men in Pursuit of a Forlorn Hope, 1779 -1784, Maine Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 19 (Fall 1979 ), pp. 73–90

- Faibisy, John D. Penobscot, 1779: The Eye of a Hurricane Maine Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 19 (Fall 1979 ), pp. 91–117.

- Jones, E. Alfred, The Loyalists of Massachusetts, Their Memorials, Petitions and Claims, London: Saint Catherine Press, 1930, pp. 70–71

- Nutting to Germain, London, January 17, 1778, Public Records Office, London: Colonial Office Papers. CO. 5, America and West Indies, 1689-1819, vol. 155, no. 88, Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa

- Buker, p. 5

- Germain to Clinton, Whitehall, September 2, 1778, no. 11, American Manuscripts (Carleton Papers), 1775-1783 (transcripts), Public Archives of Canada. Ottawa, vol. 7, no. 27, pp. 239-41

- George Nafziger, Battle of Penobscot August 1779, United States Army Combined Arms Center.

- "Privateering and piracy: the effects of New England raiding upon Nova Scotia during the American Revolution, 1775-1783". U. Mass. Amherst. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- "BEVERLY PRIVATEERS IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION". colonialsociety.org/. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- "Privateering and piracy: the effects of New England raiding upon Nova Scotia during the American Revolution, 1775-1783". U. Mass. Amherst. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- "Privateering and piracy: the effects of New England raiding upon Nova Scotia during the American Revolution, 1775-1783". U. Mass. Amherst. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- "The Penobscot Expedition: A Terrible Day for the Patriots". warfarehistorynetwork.com. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- "BEVERLY PRIVATEERS IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION". colonialsociety.org/. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- "Privateering and piracy: the effects of New England raiding upon Nova Scotia during the American Revolution, 1775-1783". U. Mass. Amherst. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- Buker, p. 6

- Buker, p. 7

- Buker, p. 13

- Buker, p. 15

- Buker, p. 14

- Bicheno, pp. 149–150

- Calef, John MD (published under "J.C. Esq. a Volunteer") The Siege of Penobscot by the Rebels containing a Journal of the Proceedings of His Majesty's Forces against the Rebels in July, 1779, and a Postscript, giving some Account of the Country, &c, &c (short title) London: Printed for G. Kearsley, in Fleet-Street, and Ashby and Neele, (late Spilsbury's) Russel-Court, Covent Garden. 1781. pp. 3-6

- Buker, p. 37

- A Naval History of the American Revolution: Chapter XII, The Penoboscot Expedition, http://www.americanrevolution.org/navy/nav12.html

- Buker, pp. 36,39–40

- Buker, p. 41

- Goold, quoting General Wadsworth

- Buker, pp. 42–45

- Williams and Chase, p. 89, quoting William D. Williamson's History of Maine. Williamson got this casualty information directly from General Wadsworth

- Calef, pp 8-10

- Deposition of Allan Hallet of the Brig Active sworn to in Court, September 25, 1779, Massachusetts State Papers, 1775-89, 2: 34, Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, Record Group 360, National Archives Microfilm Publication M247, Roll 79, Item 65

- Lovell to Saltonstall, August 11, 1779; Calef, p.36

- Adoption of the "Report of the Committee for Enquiring into the Failure of the Penobscot Expedition", Chapter 459 of "The Acts and Resolves Public and Private of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay 1779-1780" October 7, 1779

- The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, volume XXI, page 217, Boston: Wright & Potter, 1922, https://books.google.com/books?id=BVxHAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA217

- Joseph Williamson, "Sir John Moore at Castine during the Revolution," Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Second Series, Volume II, 1891, p. 403.

- Goold, quoting William Moody's Journal

- Buker, p. 49

- Buker, pp. 50–52

- Buker, p. 56

- Buker, p. 66

- Campbell, p. 497

- "The Penobscot Expedition: A Terrible Day for the Patriots". warfarehistorynetwork.com. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- Bicheno, p. 152

- "Sir George Collier's Account of Penobscot" London Gazette, Extraordinary Edition, September 24, 1779

- "Penobscot Expedition Archaeological Project Field Investigations 2000 and 2001 FINAL REPORT". denix.osd.mil. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- Williams and Chase, p. 90

- Buker

- Burrage, Henry S. Maine in the Northeastern Boundary Controversy. Portland: Marks Printing House (Printed for State of Maine), 1919. p.21

- Maine Historical Society Collections II, p. 400

- Nova Scotia Royal Gazette, September 14, 1814, p. 3; Niles Weekly Register, October 6, 1814, p. 52

- Whipple, Joseph History of Acadia, pp. 91-92 and 98

- Young, George F.W. The British Capture & Occupation of Downeast Maine 1814-1815/1818, Chapter VI

- "Defence". Archived from the original on 2010-04-25. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- "Penobscot Expedition 1779: Making Revolutionary History".

- Kamiya, Gary. "The Five-Second Cancellation of Abraham Lincoln". The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

Notes

- Navy Board Eastern Department

Boston July 13, 1779

To Dudley Saltonstall Esqr Commander of the Ship Warren

Your ship being ready for the Sea you are to take under your direction the Brigt Diligent & all the Vessells belonging to or employed by this State for an Expedition Against the Enemy at Penobscot & proceed with them on said Expedition after Rendezvousing at Townsend where you will meet with & take with you the Sloop Providence Brigt Active & any other Vessell destined to the same Service. You are to take every Measure & use your Utmost Endeavours to Captivate Kill or destroy the Enemies whole Force both by Sea & Land & the more effectually to answer that purpose you are to Consult Measures & preserve the greatest harmony with the Commander of the Land Forces that the Navy & Army may Cooperate & assist each other when that business is Effected or if on your Arrival you shall find the Enemy have left Penobscot & that shore & retired out of your reach You are then to take with you the Sloop Providence & Brigt Diligent who are Ordered to Cruise with you and under your Command & after furnishing the Commanders of them with Copys of your orders & proper directions & Signals proceed immediately to &c. &c.

The aforegoing is a true Extract of the orders given by the Navy Board Eastern department to Captain Saltonstall so far as they relate to the Penobscot Expedition as appears of record.

Attest Willm Story C N B E d - Warrant for Court Martial On Dudley Saltonstall Esq.

September 7th 1779

Navy Board Eastern Department

To Saml. Nicholson Esq. Captain Commander in the Navy of the United States of America.

Whereas the principal part of the Fleet employed in the Expedition against the Enemy at Penobscot Particularly the Ship Warren, Sloop Providence, Brigantine Diligent, all under the Command of Dudley Saltonstall Esq. late Captn. And Comdr. Of the Continental Frigate Warren, have been destroyed and lost as is Suggested by the bad conduct of the said Dudley Saltonstall, & his conduct is now therefore become a proper subject for the Examination and Judgment of Court Martial.

We do therefore by virtue of the Power and Authority with which we are vested hereby Order and Direct that a Court Martial be called for that purpose, which Court Martial we do hereby appoint to consist of you the aformd. Saml. Nicholson as President - and of John Peele Rathbone - and Samuel Tucker Esq. Captain in the C. Navy - and of Mr. David Phipps. Adam Thaxter - and Hopley Yeaton first Lieutenants in the C. Navy - and of Seth Baxter - Edmond Arrowsmith - and Willm. Jones Captains of Marines in C. Navy - and of Saml. Pritchard - William Waterman - and Peter Green Lieutents. Of Marines in C. Navy - who together are to constitute this Court Martial, to set on board the Continental Ship Deane now lying in the Harbour of Boston, on Tuesday the 14th Day of this Inst. September. at 10 Clock in the Forenoon with power to Adjourn from Time to Time and Place to Place as occasions may require - And the Court Martial being so constituted and met at Time and Place aforesd. and Qualified agreeable to the Resolutions of Congress, are to consider & thoroughly examine the Conduct of the said Dudley Saltonstall during his command aforesd. and hear & examine all such Matters & Informations, as shall then be bro't before you, relating to the Conduct of the said Dudley Saltonstall during his aforesd. Command on proper Evidence, thereon to Try, Determine, & make up Judgment on the said Dudley Saltonstall for the aforesd. Losses, & his Conduct during his Command aforesaid. According to the Rules of Naval Discipline, and the Articles for the Regulation of the American Navy.

And if in any Respect found guilty of being by his Conduct the occasion of the Disgrace and Losses aforesd. To pass sentence accordingly - which sentence you are to return to us with the Evidence & other Papers had before you.

And you are hereby Authorized, and Empowered to Order and Direct the attendance of any Master at Arms - Sergeants of Marines, or any other Officer, or Seaman of the C. Navy, who may be wanted as an Attendant on your said Court, & also to Summon such Witnesses as you may suppose able to give Testimony in the Matter.

And for so doing this shall be to you, & each of you Members of said Court Martial, hereby appointed, and all others concerned a sufficient Warrant.

Given under our Hands at Boston this Seventh Day of September AD 1779 - In the fourth year of the Independence of the United States of America.

W(illiam) Vernon

J(ames) Warren

Sources

- Bicheno, Hugh (2003). Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolutionary War. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-715625-2. OCLC 51963515.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo (1966). Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence, 1763–1783. London: Cassell & Company. ISBN 0-304-29296-6.

- Buker, George E. (2002). The Penobscot Expedition: Commodore Saltonstall and the Massachusetts Conspiracy of 1779. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-212-9. OCLC 47869426.

- Campbell, John; Berkenhout, John; Yorke, Henry Redhead (1813). Lives of the British Admirals: Containing Also a New and Accurate Naval History, from the Earliest Periods. Vol. V. London: C. J. Barrington. OCLC 17689863.

- Goold, Nathan (1831). Bagaduce Expedition, 1779: Collections of the Maine Historical Society. Vol. X, 1899, 2nd Series.

- Hunter III, James W (2003). "Penobscot Expedition Archaeological Project Field Report" (PDF). Naval Historical Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-04-08. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- Stewart, David (1977) [1822]. Sketches of the Character, Manners, and Present State of the Highlanders of Scotland; with Details of the Military Service of the Highland Regiments. Vol. II. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers.

- Wheeler, George A (1875). History of Castine: Battle Line of Four Nations. Bangor, Maine: Burr & Robinson. OCLC 2003716.

- Williams and Chase (1882). History of Penobscot, Maine, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches. Cleveland, OH: Williams, Chase & Co.

Further reading

- Thesis – Penobscot Expedition

- Jonathan Mitchell's Regiment – Begaduce Expedition. Maine Historical Society

- British journal of the attack

- Paul Revere's account of the attack

- Cornwell, Bernard (2010). The Fort. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-733172-7. Retrieved 2018-09-01. A historical novel depicting the Penobscot Expedition, with a non-fiction "Historical Note" (pp. 451–468) on sources and key details.

External links

- Revolutionary War-Era Swivel Gun reveals its secrets (about a gun raised from Penobscot Bay)

- "The Ancient Penobscot, or Panawanskek." The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries concerning The Antiquities, History, and Biography of America. Third Series, Vol. I, No. II; Whole Number, Vol. XXI, No. II, February, 1872. Morrisina, N.Y., Henry B. Dawson. pp. 85–92.

- A Short History of the Penobscot Expedition