Portuguese nobility

The Portuguese nobility was a social class enshrined in the laws of the Kingdom of Portugal with specific privileges, prerogatives, obligations and regulations. The nobility ranked immediately after royalty and was itself subdivided into a number of subcategories which included the titled nobility and nobility of blood at the top and civic nobility at the bottom, encompassing a small, but not insignificant proportion of Portugal's citizenry.

The nobility was an open, regulated social class. Accession to it was dependent on a family's or, more rarely, an individual's merit and proven loyalty to the Crown in most cases over generations. Formal access was granted by the monarch through letters of ennoblement and a family's status within the noble class was determined by continued and significant services to Crown and country. Living outside the laws of the nobility immediately revoked an individual's status and that of his descendants.

Unlike many other European countries, power in Portugal was effectively centralised in the Crown, despite attempts to the contrary by the nobility, most notably during the reign of King João II, as was the capacity to confer nobility and other awards as well as to refuse them.

During the Portuguese monarchy, as well as enjoying the most privileged status and access to Court, members of the nobility, particularly the titled nobility, including major hierarchs of the Roman Catholic Church, held the most important offices of State – administrative, judicial, political and military. With the needs of an ever larger global empire and the rise of mercantilism, and growth in importance of the mercantile class, privileges were increasingly widened, eroding the relative power held particularly by the titled nobility, a situation which was accelerated significantly during the reign of King José I, as a result of the policies of his prime minister, the Marquis of Pombal, himself recently elevated to the highest echelons of the nobility.

With the Portuguese Constitution of 1822 and the introduction of a constitutional monarchy, all noble privileges were extinguished, and the influence of the traditional nobility declined significantly. Notwithstanding, nobility – hereditary or otherwise – continued to be recognised in law as a status with certain prerogatives, albeit merely honorific ones, until the establishment of the Portuguese Republic in 1910.

Descendants of Portugal's hereditary nobles have continued to bear their families' titles and coats of arms according to the standards and regulations established before the Republic, and currently sustained by the Institute of Portuguese Nobility (Instituto da Nobreza Portuguesa), whose honorary president is D. Duarte Pio, Duke of Braganza, head of the House of Braganza and presumptive heir to the Portuguese throne.

History

The Portuguese nobility can be traced back to the reign of Alfonso VI of Leon, whose reign saw the sons of Leonese nobility established as gentry in the north of Portugal, between the Minho River and the Douro River. This was the region of the sun and the most powerful men of the kingdom. They united nobility of birth to the authority and prestige of public office.

They were followed in the hierarchy, in descending order, by infancies, cavaleiros (knights) and escudeiros (squires). A title of Spanish origin, filho de alguém, applied to senior functionaries and gave rise to the word fidalgo, who, in the 14th century, became widespread and went on to name all of noble lineage, thereby designating the highest class of the nobility, without distinction of rank.

Renaissance

By the time of the reign of Manuel I of Portugal (1495–1521), during the Portuguese Renaissance, for example, when they were appointed captains of the fleet of Pedro Álvares Cabral, who arrived in Brazil on April 22, 1500, the Portuguese nobility already had registers dating back to the 12th century. The noble members of Cabral's fleet followed this feature, since most descended from families of Castile and León, who had settled in Portugal, who had already rendered several generations of service. The few exceptions – such as Bartolomeu Dias, who received his rank and arms which he transmitted to his descendants – show the importance attributed at this period to the discoveries made.

It was also the reign of King Manuel I that rules were established that define the use of the degrees of nobility (hereditary titles), and the use of heraldic arms, preventing abuses in the adoption of both and establishing the rights of the nobility. The nobles were subject to the king and were arranged in two orders, each with three degrees:

- First Order

- 1st grade: Fidalgo Cavaleiro

- 2nd grade: Fidalgo Escudeiro

- 3rd grade: Moço Fidalgo

- 4th grade: Fidalgo Capelão (for ecclesiastics)

- Second Order

- 1st grade: Cavaleiro Fidalgo

- 2nd grade: Escudeiro Fidalgo

- 3rd grade: Moço da Câmara

- 4th grade: Capelão Fidalgo (for ecclesiastics)

All nobles were considered vassals of the King of Portugal. To rise in status, a noble was expected to demonstrate loyalty and service to the king.

The battle of Alcácer Quibir in 1578 was an unmitigated disaster for Portugal. King Sebastian of Portugal died on the battlefield along with most of the Portuguese nobility, leading to the end of the Aviz dynasty.

Afonso I, Duke of Braganza, founder of the House of Braganza

Afonso I, Duke of Braganza, founder of the House of Braganza_-_Autor_desconhecido.png.webp)

16th century Portuguese illustration from the Códice Casanatense, depicting a Portuguese nobleman with his retinue in Portuguese India

16th century Portuguese illustration from the Códice Casanatense, depicting a Portuguese nobleman with his retinue in Portuguese India Maria, Duchess of Viseu, one of the richest women in Europe during the Renaissance

Maria, Duchess of Viseu, one of the richest women in Europe during the Renaissance

Though the 15th and 16th centuries were rich in acts of bravery and heroic deeds, the deeds related to the Age of Discoveries were not represented symbolically for new arms in Portuguese blazon. Few were granted, and not all heraldic grants were recorded. This did not occur with those involved in combat, especially during the occupation of northern Africa, which feature many coats of arms with their own attributes, such as "Moorish head." The heraldry of the Discoveries is restricted to inherited symbols from the family, or canting arms, such as Nuno Leitao da Cunha, with nine wedges (cunhas), or the goats of Cabral, without suggesting or representing the challenges found in the sea and its conquest. The arms of Nicolau Coelho, which contain a base undy silver and blue, which can symbolize the conquered sea, is a rare exception.

Modern era

.jpg.webp)

In the first half of the 18th century, the Royal Equestrian Academy (today known as the Portuguese School of Equestrian Art) was founded by King João V of Portugal as a riding school exclusively accessible to the Portuguese royal family and the nobility. Good horsemanship was and still is considered a hallmark of the Portuguese nobility, equestrianism continuing to this day to be the traditional sport of the class.

Following the Proclamation of the Portuguese Republic in 1910, the nobility was officially disbanded and ennoblement was prohibited under the Portuguese Constitution. Notwithstanding, although the status of nobility has not been recognised in law since 1910, legitimate titles of nobility (those granted by a reigning monarch before the 5th October 1910) have been given legal recognition and protection, including under Article 26 of the Portuguese Constitution, in conjunction with articles 70 and 72 of the Civil Code, as established by decision of Portugal's Supreme Court of Justice in 2014.[1]

Duarte Nuno, Duke of Braganza, created the Portuguese Council of Nobility during the Republic to study the former monarchy's laws and grants of nobility, and to update the genealogies of ennobled families, maintaining records on the transmission of hereditary titles in accordance therewith. The predominant activity of the Council was the identification of living heirs to historical titles and coats of arms.

After Dom Duarte Nuno's death, his son Duarte Pio, Duke of Braganza, declared the Council of Nobility disbanded, following criticism in relation to a handful of questionable decisions. Subsequently, the Instituto da Nobreza Portuguesa was established by representatives of Portugal's titled nobility, with the acquiescence and support of the Duke of Braganza – its honorary president – as a self-regulating private body which continues the work and maintains the records of the original Council of Nobility.

.png.webp) John II of Braganza, first Braganza to become King as John IV of Portugal

John II of Braganza, first Braganza to become King as John IV of Portugal Duarte de Sousa da Mata Coutinho, an untitled, but powerful noble and hereditary High-Courier of the Kingdom

Duarte de Sousa da Mata Coutinho, an untitled, but powerful noble and hereditary High-Courier of the Kingdom Leonor de Almeida Portugal, 4th Marquise of Alorna, notable author and poet popularly known as Alcipe

Leonor de Almeida Portugal, 4th Marquise of Alorna, notable author and poet popularly known as Alcipe.jpg.webp)

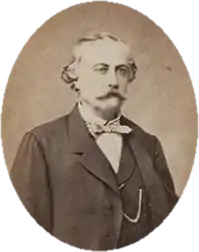

Nuno de Mendoça Rolim de Moura Barreto, 1st Duke of Loulé and Prime Minister under King Pedro V and King Luís I

Nuno de Mendoça Rolim de Moura Barreto, 1st Duke of Loulé and Prime Minister under King Pedro V and King Luís I

Hierarchy of the Nobility

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

.png.webp)

The ranks of the titled nobility, although similar to those in other European countries, have their idiosyncrasies in Portugal. They are as follows:

- Royal Dukedoms

- Dukedoms

- Marquisates

- Countships

- Viscountcies with honours of Grandeza

- Viscountcies

- Baronies

- Lordships (abolished by the Charter of 19 May 1863)

- Fidalgo

The holders of all titles of Count, Marquis and Duke were automatically imbued with Grandeza of the kingdom of Portugal. The rank of Grandeza was automatic also for Bishops, Archbishops, Cardinals and the Patriarch of Lisbon, as well as for the Peers of the Realm during the constitutional monarchy when the House of Peers was established in the Portuguese Cortes. In addition, in rare circumstances, viscountcies were given the attribute of "Honras de Grandeza", placing them on a rank equivalent to countships. This is the case with the viscountcies of Asseca and Balsemão, for example.

In extraordinary circumstances, certain titleholders were granted the hereditary title of "Parente d'El Rei". As well as denoting a historic blood relationship with the Crown, it was a sign of exceptional merit and raised the titleholder's status above that of all other titled nobility, with the exception of royal dukes. Examples include the dukes of Cadaval, marquesses of Lavradio and Valença, and counts of Óbidos.

All nobles titles were effectively hereditary but most required new concessions for their respective heirs. In rare occasions, these were given to members of the same family that were not the immediate heir. Titles were granted:

- De juro e herdade: in perpetuity, according to the law, where to be inherited a title required no further concession from the Crown or the State, but merely its acknowledgement.

- Em vida: limited to 1, 2, 3 or 4 holders, as specified by the grant, thereafter requiring a specific concession from the Crown to be inherited or renewed.

In Portugal and Brazil, the honorific Dom (pronounced [ˈdõ]) is often used for men who belong to the House of Braganza.[2] Otherwise, in Portugal, it is used by members of families of some of its titled nobility.[3] Unless ennobling letters patent specifically authorised its use, Dom was not attributed to members of Portugal's untitled nobility: Since hereditary titles in Portugal descended according to primogeniture, the right to the style of Dom was the only apparent distinction between cadets of titled families and members of untitled noble families.[3]

Fidalgos constituted the lowest rank of nobility of blood.

_-_Colijn_de_Coter_(attributed)_(cropped).png.webp)

Royally-held noble titles

In addition to their royal titles, members of Portugal's royal family have held a number of noble titles, either through acquisition prior to the family's accession to the throne or by grant of the monarch. Following the proclamation of the republic in 1910, these titles have been used by various members of the royal family, notably by the Duke of Braganza's younger brothers and by his three children. The following are titles that have been held at various times by Portuguese royalty:

Titles held by the monarch

Titles held by the heir to the Portuguese throne

.jpg.webp)

Titles held by the heir to the royal heir

Titles held by the monarch's children

Other titles bestowed on royalty

See also

Sources

References and notes

- "Acórdão do Supremo Tribunal de Justiça".

- Angus Stevenson, ed. (2007). Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. 1, A–M (Sixth ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 737. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2.

- Tourtchine, Jean-Fred (September 1987). "Le Royaume de Portugal - Empire du Bresil". Cercle d'Études des Dynasties Royales Européenes. III: 103. ISSN 0764-4426.

- Title held by the reigning monarch's 2nd child

- Title held by the reigning monarch's 3rd child

_mini.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)

_-_Genealogia_de_D._Manuel_Pereira%252C_3.%C2%BA_conde_da_Feira_(1534)_(cropped).png.webp)

_-_Lesser.png.webp)