Patrick Lyon (blacksmith)

Patrick Lyon (1769, Edinburgh, Scotland – April 15, 1829, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) was a Scottish-born American blacksmith, mechanic and inventor. After being falsely accused and imprisoned for a 1798 bank robbery, he became a working class hero.[1] A self-made businessman, he was among the foremost American makers of hand-pumped fire engines.[2]

Artist John Neagle's portrait of him, Pat Lyon at the Forge (1826–27), alludes to his unjust imprisonment, and is an iconic work in American art.

Biography

Lyon and his parents moved to London when he was a child, and he worked in various factories, beginning at about age 10.[3] He emigrated to Philadelphia in November 1793,[3] where he worked as a journeyman, before opening his own business in May 1797.[3]

Bank of Pennsylvania robbery

.jpg.webp)

Prior to 1798, the Bank of Pennsylvania conducted business from an office in Philadelphia's Masonic lodge.[4] Following a robbery attempt at the lodge, the bank signed a lease with Carpenters' Hall, and hired contractor Samuel Robinson to prepare the hall for the bank's operations.[4] Two previous banks had operated out of Carpenters' Hall, while their permanent buildings were under construction.[4] Robinson hired Lyon to create new locks for the vault in the cellar of the hall, and brought the vault's iron doors to Lyon's shop on August 11.[5] Lyon completed his work on August 13, and the doors were reinstalled that day.[5]

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania served as the temporary capital of the United States from 1790 to 1800. In 1793, one fifth of the city's population had died in a yellow fever epidemic; the disease reappeared in 1797, and again the following summer. In late-August 1798, President John Adams, Congress, and many of the inhabitants abandoned the city. On August 28, Lyon and his 19-year-old assistant Jamie fled Philadelphia by ship to Lewes, Delaware, but Jamie died of yellow fever within two days of their arrival.[5]

On the night of August 31/September 1, while much of the city was deserted, the Bank of Pennsylvania's reserves of $162,821 in cash and Spanish gold were stolen from the vault in Carpenters' Hall.[6] There were no signs of thieves having broken into the building, and Lyon's locks on the iron doors were undamaged. Lyon was still in Delaware weeks later where he learned that he was the prime suspect in the robbery, and returned to Philadelphia to clear his name. He met with officers of the bank and the mayor of Philadelphia, but they came away suspecting that Lyon had secretly made an extra set of keys for the robbery.[7] In the midst of the worsening yellow fever epidemic, he was arrested without evidence and thrown into Walnut Street Gaol: "Upon the presumption that his locks were so good nobody but himself could open them, he was thrown into prison and there kept for a long time."[8]

The robbery turned out to be an inside job. Isaac Davis, a member of the Carpenters' Company, and Thomas Cunningham, the night watchman at Carpenters' Hall, were the only conspirators. Cunningham died of yellow fever within days of the robbery, and Davis came under suspicion after making major deposits into a number of Philadelphia banks, including the Bank of Pennsylvania.[9] Davis confessed, and was granted a pardon from Pennsylvania's governor in exchange for returning the bank's money. Davis returned all but $2,000, disappeared from Philadelphia, and never served a day in jail.[4]

Even after Davis's October 1798 confession, Philadelphia's high constable John Haines would not release Lyon, but reduced his bail from $150,000 to $2,000 (still, more than the blacksmith's net worth). Haines convened a grand jury in January 1799, but it refused to indict Lyon and he was released.[4]

Narrative

Lyon wrote a narrative about his imprisonment: The Narrative of Patrick Lyon, who suffered three Months severe Imprisonment in Philadelphia Gaol, on merely a vague Suspicion of being Concerned in the Robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania: with his Remarks thereon (1799).[3] In its introduction, he pleaded for equal justice for rich and poor.[1] The frontispiece of the publication was an engraved portrait by Philadelphia artist James Akin, and showed a 30-year-old Lyon in Walnut Street Prison, incongruously dressed as a gentleman, seated on a Chippendale chair, and holding a technical drawing and calipers.

An 1800 British review of the Narrative was dismissive of Lyon's grammar and writing style, but concluded:

The picture he has drawn of the judicial exercise of justice in Pennsylvania, as well as of the Police, impartiality, and humanity, of a Philadelphia prison, well merit the attention of those Britons who are so forward, on all occasions, to proclaim the blessings of American liberty, to the disparagement of our own. We must not omit to mention, however, that Lyon was perfectly innocent as to the crime of which he was suspected.[10]

Lawsuit

Lyon filed a civil lawsuit for malicious prosecution and false imprisonment against the bank president, the head cashier, a bank board member and High Constable Haines. The case went to trial in July 1805. William Rawle, defense attorney for the bank, freely acknowledged that Lyon had been in southern Delaware, 150 mi (240 km) away, at the time of the robbery.[5] But Rawle also repeatedly stressed what an "ingenious" man Lyon was, implying that he had been the mastermind behind the crime.[5] The jury didn't buy Rawle's argument, found that the bankers and constable had conspired to act with malice toward Lyon, and awarded him $12,000 in damages.[4] The defendants appealed, but settled out of court with Lyon for $9,000 in March 1807, just as a second trial was about to begin.[4]

Fire apparatus

_p.417.jpg.webp)

"[Patrick Lyon] had a profound effect on the development of fire apparatus in the United States."[2] Other "engine-builders were soon superseded by the famous locksmith, who invented a new and improved fire-engine, which he announced would throw more water than any other, and with a greater force."[11] Lyon's patent for an "engine for throwing water" was approved on February 12, 1800.[12] His design featured a surge tank encased in a square column at the center of the engine, vertical pump cylinders, double decks, and hinged lever bars at the ends. These came to be known as "Philadelphia-style hand pumpers," and he built examples for the Good Will and Philadelphia Fire Companies in 1803.[11]

Philadelphia was one of the first American cities to build a gravity-fed municipal water system. In 1802, Frederick Graff "designed the first post-type hydrants in the shape of a 'T' with a drinking fountain on one side and a 4-1/2-inch water main on the other."[13] Initially, these hydrants were used to fill buckets that were passed by a bucket brigade to fill a fire engine's reservoir. In 1804, Lyon invented the first hose wagon, which transported 600 ft (180 m) of copper-riveted leather hose to the hydrants. Its bed also could be used as an additional reservoir. The use of hoses eliminated the need for bucket brigades, and allowed 11 men to do the work of 100.[13] A description of Lyon's hose wagon:

It was an oblong box upon wheels, six feet nine inches long by two feet six inches wide and two feet deep; the hose was carried in the box without a cylinder. It was used as a reservoir also when the hose was in service for holding water to feed the engines. The box had arms at the front and back to assist in changing its position, and lanterns on either side with candles; this wonder of the age cost ninety-eight dollars. The first fire at which the hose company turned out was ... on the 3d of March, 1804. [T]his was the first occasion at which the first hose-carriage was in service at a fire in Philadelphia." In August, 1804, the bell apparatus was affixed to the carriage. In March, 1805, a railing was put around the top to enable the company to carry eight hundred feet of hose.[14]

Lyon built engines for other Philadelphia fire companies – the Pennsylvania, United States, Hand-in-Hand, Good Intent and Washington companies – as well as for fire companies in cities and towns in Pennsylvania and other states.[11]

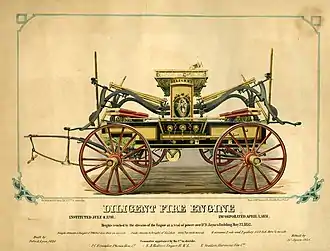

Diligent Fire Engine

Lyon's masterpiece was the 1820 engine Diligent,[11] a double-decker, end-stroke hand pumper built for Philadelphia's Diligent Fire Company, and "one of the most powerful pumpers in the United States."[15] Planks laid over the engine's reservoir created twin upper decks, where eight men pumped (four facing each end), and hinged lever bars that folded down allowed an additional sixteen men (eight at each end) to pump from the ground.[16] The fire company was so pleased with the engine that they made Lyon a lifetime member.[2]

In a May 22, 1852 contest of man-versus-steam, the 32-year-old Diligent competed against the new steam-powered pumper Young America, made in Cincinnati and owned by a Baltimore fire company.[17] Before a crowd of some 50,000, at 3rd & Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, Diligent and Young America shot streams of water against or over an early skyscraper, the 129 ft (39 m) Jayne Building.[17] Diligent was triumphant in all three tasks—shooting a single stream of water to a height of 196.5 ft (59.9 m) using a 1-inch nozzle; shooting two simultaneous streams to a height of 155.75 ft (47.47 m) using 3/4-inch nozzles; and shooting four simultaneous streams to a height of 134 ft (41 m) using 1/2-inch nozzles.[17] Diligent remained in service until after the Civil War.[18]

Surviving engines by Lyon

It is estimated that Lyon built about fifty fire engines over the course of his career.[19] At least eight of them survive:

- A circa-1800 hand pumper, built for the Volunteer Fire Company of Philadelphia, is in the collection of the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.[20]

- An 1803 hand pumper, "Pat Lyon," built for the Jonestown Engine Company of Jonestown, Pennsylvania, is the centerpiece of the town's fire museum.[21]

- An 1803 hand pumper, "Lazaretto," built for the Philadelphia Lazaretto (quarantine hospital), Essington, Pennsylvania, is in the collection of the Lazaretto Interpretive Museum.

- An 1806 double-decker hand pumper, built for the Independent Fire Company of Annapolis, Maryland, is in the collection of the Fire Museum of Maryland.[22]

- An 1809 double-decker hand pumper, built for the Friendship Fire Company of Orwigsburg, Pennsylvania, is in the collection of the Schuylkill Historical Fire Society Museum in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania.[23]

- An 1812 double-decker hand pumper, "Old Washy," built for the Washington Fire Company of Newtown, Pennsylvania, is exhibited in the town's old firehouse.[24]

- An 1812 double-decker hand pumper, built for the American Engine Company of Philadelphia. The engine was purchased by Womelsdorf, Pennsylvania in 1846, it remained in service until about 1890, and it is still owned by the borough.[19] Currently on display at the Reading Area Firefighters Museum, Reading Pennsylvania

- An 1820 double-decker hand-pumper, built for the Rainbow Fire Company of Reading, Pennsylvania, is in the collection of the Historical Society of Berks County.[25]

Personal

Lyon married a woman named Ann, and their daughter Clementina was born in 1796. At the time of his 1798 imprisonment, Lyon was a recent widower. Ann had died of yellow fever,[5] and Clementina died at age 9 months, in March 1797, and was buried in the churchyard of St. Peter's Episcopal Church (Philadelphia).

Lyon owned a house on Library [now Sansom] Street, east of 5th Street.[11] He was a member of Philadelphia's St. Andrew's Society, a charitable organization that provided aid to Scottish immigrants.[11] He was also a Freemason.[26]

Lyon was buried in 1829 in an unmarked grave in the same churchyard as his daughter. Burial records note: "The grave of the celebrated 'Pat Lyon' adjoins [Clementina Lyon's], no stone,"[27] but do not list Ann Lyon among the burials.

Obituary:

DIED—at Philadelphia, Patrick Lyon, hydraulic engine maker, who was one of the most ingenious workers in mettle [sic, metal], in the United States, especially as a blacksmith; so much so, that when the [B]ank of Pennsylvania was robbed many years ago, he was arrested and tried, (though acquitted), for the crime, mainly, if not almost exclusively, for the reason of a belief that he was the only man capable of unlocking the vaults, by false keys. For this prosecution he recovered high damages.[28]

Pat Lyon at the Forge

On November 4, 1825, Lyon commissioned painter John Neagle to paint his portrait:[26]

I wish you, sir, to paint me at full length, the size of life, representing me at the smithery, with a bellows-blower, hammers and all the et-ceteras of the shop around me. I wish you to understand clearly, Mr. Neagle, that I do not desire to be represented in this picture as a gentleman—to which character I have no pretensions. I want you to paint me at work at my anvil, with my sleeves rolled up and a leather apron on. I have had my eyes upon you. I have seen your pictures, and you are the very man for the work.[29]

Neagle measured everything in Lyon's shop, including the sitter: "five feet six inches and three quarters in his boots."[26] At Lyon's request, Neagle introduced the Walnut Street Gaol into the portrait:

It was seen with its cupola through the window of his shop, which stood on Library street. This was a whim of Lyon, to commemorate his unjust imprisonment in the building on the charge of picking the locks of the old Bank of Pennsylvania and robbing it of a large amount of money. Many objected to the introduction of the prison into the picture, but Judge Hopkinson, who was his counsel in this very interesting trial, approved of the whim, saying: "That is right, Lyon: preserve the recollection of the old prison, as it is a very important part of your history."[29]

The completed portrait made its public debut in Philadelphia in May 1827, at the 16th annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), under the title: "Full length Portrait of Mr. Patrick Lyon, representing him as engaged at his anvil."[30] Later that year, critic William Dunlap praised the portrait when it was exhibited in New York City at the National Academy of Design:

Patrick Lyon the Blacksmith.—One of the best, and most interesting pictures in the present exhibition of the National Academy at the Arcade Baths, is a blacksmith standing by his anvil, resting his brawny arm and blackened hand upon his hammer, while a youth at the bellows, renews the red heat of the iron his master has been laboring upon.

This picture is remarkable, both for its execution and subject. Mr. Neagle of Philadelphia, the painter, has established his claim to a high rank in his profession, by the skill and knowledge he has displayed in composing and completing so complicated and difficult a work. The figure stands admirably; the dress is truly appropriate; the expression of the head equally so; and the arm is a masterly performance. The light and indications of heat, are managed with perfect skill. In the background at a distance, is seen the Philadelphia prison, and thereby "hangs a tale," whether true in all particulars, is perhaps of little moment; I give it as I took it.[31]

Lyon lent the portrait to the Boston Athenaeum for an 1828 exhibition, and the club purchased it from him for $400.[26] He then commissioned Neagle to make a second version, which was exhibited at PAFA's 18th annual exhibition in May 1829, a month after Lyon's death: "Portrait of the late Patrick Lyon, at the Forge, the second picture of this subject."[30]

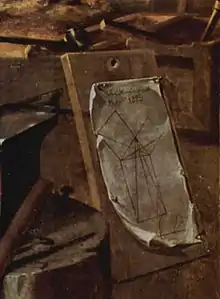

The second version is slightly larger, Neagle's brushwork is looser, and Lyon's facial expression is sterner. But the only major departure from the original is the addition of a board in the right foreground, to which is nailed a drawing illustrating the Pythagorean theorem.[26] Neagle signed and dated the 1829 portrait above the Pythagorean theorem illustration.

The original portrait – 93.75 in (238.1 cm) by 68 in (170 cm), and dated: "1826 & 7" – is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[32] The second version – 94.5 in (240 cm) by 68.5 in (174 cm), and dated: "1829" – is owned by PAFA,[33] as is a c.1826 compositional study for the original.[34] Neagle's head-and-bust study of Lyon is in the collection of the Philadelphia History Museum,[35] as is a compositional study for the 1829 version.[36] Another study is in private hands.[37]

In popular culture

- A February 22, 1832 parade in Philadelphia, celebrating the 100th anniversary of George Washington's birth, featured a horse-drawn float with blacksmiths pounding anvils before an image of "Pat Lyon at the Forge."[38]

- The Mechanic Fire Company of Philadelphia, established 1839, adopted "Pat Lyon at the Forge" as their emblem, and painted it on their parade hats.[39] One of these parade hats set an auction record when it sold at Sotheby's NYC in January 1988 for $27,500.[40]

- The Locksmith of Philadelphia – 1839 serialized novel by Joseph Howe[41]

- Patrick Lyon, or The Philadelphia Locksmith – 1843 play by James Rees[42]

- Pat Lyon, the Master Locksmith – 1890 youth novel by Charles Morris

- Robbery in Philly: The Ninth Token (Time Game Book 9), 2019 youth book/game. As Patrick Lyon is held in a Philadelphia prison, Marcus and Samantha Willoughby gather evidence to prove he is innocent of bank robbery.

References

- Ransom R. Patrick, "John Neagle, Portrait Painter, and Pat Lyon, Blacksmith," The Arts Bulletin, vol 33, no. 3 (September 1951), pp. 213-251. (subscription $)

- Robert Burns, "When the Watchman Spun his Rattle, Cry Was 'Throw Out Your Buckets!'" Fire Engineering Magazine, vol. 120 (July 1976).

- Patrick Lyon, The Narrative of Patrick Lyon, who suffered three Months severe Imprisonment in Philadelphia Gaol, on merely a vague Suspicion of being Concerned in the Robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania: with his Remarks thereon. Philadelphia: Printed by Francis and Robert Bailey, at Yorick's Head, No. 116, High-Street. 1799.

- Ron Avery, "Carpenters' Hall — America's First Bank Robbery," from ushistory.org Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Laura Rigal, The American Manufactory: Art, Labor, and the World of Things in Early Republic (Princeton University Press, 2001), pp. 179-203.

- "America's First Bank Robbery". Carpenters' Hall. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- "What Not to Do After Robbing a Bank: Put the Money Right Back". InsideHook. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- "Old Landmarks in Philadelphia," Scribner's Monthly Magazine, vol. 12, no. 2 (June 1876), p. 165.

- "The Bank Robber who deposited the money in the same bank". A Silly Point. 2020-09-04. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine, vol. 5, no. 2 (April 1800), Anti-Jacobin Press, Peterborough-Court, Fleet Street, London, pp. 556-557.

- John Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884, Volume 3 (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Company, 1884), p. 1907.

- Joseph Delaplaine, "List of American Patents," The Emporium of Arts and Sciences, Philadelphia, vol. 1, no. 5 (September 1812), p. 392.

- Robert E. Booth, Jr. and Katharine Booth, "Folk Art on Fire," catalogue essay, The Philadelphia Antiques Show (2004), p. 89.

- John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: J. M. Stoddart & Co., third edition, 1879), pp. 417-18.

- Diligent Fire Company / Veteran Fireman's Fire Hat, from National Museum of American History.

- George Escol Sellers, "Early Engineering Reminiscences," The American Machinist (New York City), vol. 9, no. 22 (May 29, 1886), p. 4.

- Diligent Fire Engine, from Library Company of Philadelphia.

- "Firemen's Jubilee: Grand Parade of Firemen in Philadelphia," The New York Times, October 17, 1865.

- 1812 Patrick Lyon "Philadelphia-Style" Hand Pumper, from Womelsdorf Volunteer Fire Company.

- Leigh Mitchell Hodges, "Old-Time Tools Tell Stories," Popular Science, vol. 149, no. 4 (October 1946), p. 117.

- History, from Jonestown Fire Company.

- 1806 Pat Lyon Pumper, from Fire Truck World.

- 1809 Orwigsburg hand pumper, from Facebook.

- The History of the Newtown Fire Association (PDF).

- Rainbow Fire Company 1820 pumper, from Historical Society of Berks County.

- Bruce W. Chambers, "The Pythagorean Puzzle of Patrick Lyon," The Art Bulletin, vol. 58, no. 2 (July 1976), pp. 225-233. (subscription $)

- Saint Peter Churchyard, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, from Interment.net

- Niles' Weekly Register (Baltimore, Maryland), vol. 36, no. 924 (May 30, 1829), p. 223.

- T. Fitzgerald, "John Neagle, The Artist," Lippincott's Magazine of Literature, Science and Education, vol. 1, no. 5 (May 1868), J. B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia, pp. 480-81.

- Peter Hastings Falk, The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Volume 1, 1807–1870 (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1888), pp. 7, 150.

- William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, Volume 2 (New York: George Scott and Co., 1834), pp. 375-376.

- Pat Lyon at the Forge, from MFAB.

- 1829 version of "Pat Lyon at the Forge," from PAFA.

- Study for "Pat Lyon at the Forge," from PAFA.

- Patrick Lyon, from SIRIS.

- Study for "Pat Lyon at the Forge," from SIRIS.

- Patrick Lyon, from SIRIS.

- "The Celebration—The Procession," The Philadelphia Album and Ladies' Literary Port Folio, vol. 6, no. 8 (February 25, 1832), p. 61.

- Jean Lipman, Elizabeth V. Warren and Robert Bishop, Young America: A Folk-Art History (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1986), illustrated, p. 78.

- Rita Reif, "Folk Art Collection," The New York Times, June 17, 1988.

- Peregrine (Joseph Howe), "The Locksmith of Philadelphia," Bentley's Miscellany, Volume 5 (London: Samuel Bentley, printer, 1839), pp. 272-280.

- The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization: American Drama (London, England: The Athenian Society, 1903), p. 46.