Park Theatre (Manhattan)

The Park Theatre, originally known as the New Theatre, was a playhouse in New York City, located at 21–25 Park Row in the present Civic Center neighborhood of Manhattan, about 200 feet (61 m) east of Ann Street and backing Theatre Alley. The location, at the north end of the city, overlooked the park that would soon house City Hall. French architect Marc Isambard Brunel collaborated with fellow émigré Joseph-François Mangin and his brother Charles on the design of the building in the 1790s. Construction costs mounted to precipitous levels, and changes were made in the design; the resulting theatre had a rather plain exterior. The doors opened in January 1798.

New Theatre (1798-99) | |

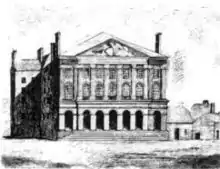

The theatre and surrounding neighborhood c. 1830. | |

| Address | 23 Park Row, New York, NY |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40.711512°N 74.007600°W |

| Owner |

|

| Type | Broadway |

| Capacity | 2,000 |

| Current use | Demolished |

| Construction | |

| Opened | January 1798 |

| Demolished | December 16, 1848 (fire) |

| Rebuilt | 1850 as 4 retail outlets by Wm. Astor and I.N. & J.J. Phelps. |

| Architect |

|

| Tenants | |

In its early years, the Park enjoyed little to no competition in New York City. Nevertheless, it rarely made a profit for its owners or managers, prompting them to sell it in 1805. Under the management of Stephen Price and Edmund Simpson in the 1810s and 1820s, the Park enjoyed its most successful period. Price and Simpson initiated a star system by importing English talent and providing the theatre a veneer of upper-class respectability. Rivals such as the Chatham Garden and Bowery theatres appeared in the 1820s, and the Park had to adapt to survive. Blackface acts and melodrama squeezed Italian opera and English drama out of their preferential positions. Nevertheless, the theatre maintained its upscale image until it burned down in 1848.

Construction

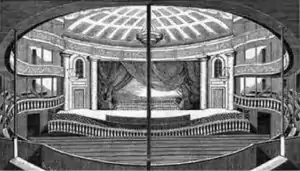

In the late 18th century, New York's only playhouse was the decaying and increasingly low-brow John Street Theatre. Tired of attending such an establishment, a group of wealthy New Yorkers began planning the construction of a new playhouse in 1795.[1] Investors bought 113 shares at $375 each to cover the estimated $42,375 cost. To plan the structure, the owners hired celebrated architect Marc Isambard Brunel, a Frenchman who had fled to New York to avoid the Reign of Terror and was then the city's engineer. Part way through construction, however, the project ran out of money. The owners sold more shares for what would eventually mount to a construction cost of more than $130,000.[2] As a cost-saving measure, Brunel's exterior design for the building was not implemented. The resulting three-story structure measured 80 feet (24 m) wide by 165 feet (50 m) deep and was made of plain dressed stone. The overall effect was an air of austerity.[3] The interiors, on the other hand, were quite lavish. The building followed the traditional European style of placing a gallery over three tiers of boxes, which overlooked the U-shaped pit.[4]

Early management

The section of Manhattan where the theatre stood was not stylish: the New Theatre, as it was called, was neighbor to Bridewell Prison, a tent city's worth of squatters, and the local poorhouse.[5] Lewis Hallam, Jr., and John Hodgkinson, both members of the John Street Theatre company, obtained the building's lease. They hired remnants of the Colonial Old American Company to form the nucleus of the theatre's in-house troupe and thus give the establishment the sheen of tradition and American culture.[6] Meanwhile, the men quarreled, and construction continued languorously. The theatre finally held its first performance on January 29, 1798, despite still being under construction. The gross was an impressive $1,232, and, according to theatre historian T. Allston Brown, hundreds of potential patrons had to be turned away.[7]

New York newspapers generally praised the New Theatre:

On Monday evening last, the New Theatre was opened to the most overflowing house that was ever witnessed in this city. Though the Commissioners have been constrained to open it in an unfinished state, it still gave high satisfaction.

The essential requisites of hearing and seeing have been happily attained. We do not remember to have been in any Theatre where the view of the stage is so complete from all parts of the house, or where the actors are heard with such distinctness. The house is made to contain about 2,000 persons. The audience part, though wanting in those brilliant decorations which the artists have designed for it, yet exhibited a neatness and simplicity which were highly agreeable. The stage was everything that could be wished. The scenery was executed in a most masterly style. The extensiveness of the scale upon which the scenes are executed, the correctness of the designs, and the elegance of the painting, presented the most beautiful views which the imagination can conceive. The scenery was of itself worth a visit to the theatre.[8]

The theatre offered performances on Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. William Dunlap eventually joined the management team. Hallam parted mid-season, and Hodgkinson waited for season's end before doing the same. Dunlap remained as sole proprietor; his expenses were so great that he had to make at least $1,200 per week to break even.[9] He left in 1805 after declaring bankruptcy. After a few more failed managers, the owners sold the theatre to John Jacob Astor and John Beekman in 1805. These men kept it until its demolition in 1848.[10]

The Park as high culture

Over three months in 1807, English-born architect John Joseph Holland remodeled the theatre's interior. He added gas lighting, coffee rooms, roomier boxes, and a repainted ceiling.

After acquiring a controlling interest in the theatre, Stephen Price became manager in 1808. He instituted a star system, whereby he paid English actors and actresses to play English dramas there. Price spent much time in England, including four years (1826–1830) as manager of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, where he recruited successful actors for the Park and for a circuit of theatres in other American cities. During this period, Price left much of the operating management of the theatre to Edmund Simpson. The Park at this point was already known for high-class entertainments, but Price and Simpson's policies helped to reinforce this as they booked English drama, Italian opera, and other upper-class bills, such as actress Clara Fisher. Price and Simpson also fostered the careers of many American performers, including Edwin Forrest and Charlotte Cushman.

The Park burned down in May 1820, and was entirely destroyed except for its exterior walls. The owners rebuilt the following year, and reopened in September 1821. The company performed at the Anthony Street Theatre during the rebuilding.[11]

In the early 1820s, the New Theatre was New York's only theatre, and the lack of competition allowed the theatre to enjoy its most profitable period.[12] The Chatham Garden Theatre was built in 1823 and provided the first real challenge to the Park's primacy; the Bowery Theatre followed in 1826. The New Theatre, having lost its newness, became known as the Park Theatre around this time. At first, each of the rivals aimed for the same upper-class audience. However, by the late 1820s and early 1830s, the Bowery and Chatham Garden had begun to cater to a more working-class clientele. In comparison, the Park became the theatre of choice for bon ton.[13] This was helped by the evolution of its neighborhood. New York home owners had steadily moved northward from Bowling Green so that by this point, the Park stood in an upper-class residential area and fronted City Hall and a large park.[14] Coffeehouses and hotels soon followed.

Despite its upper-class luster, however, some commentators found due cause to criticize the Park. In her landmark book, Domestic Manners of the Americans, the British writer Frances Trollope gave a mixed review:

The piece was extremely well got up, and on this occasion we saw the Park Theatre to advantage, for it was filled with well-dressed company; but still we saw many 'yet unrazored lips' polluted with the grim tinge of hateful tobacco, and heard, without ceasing, the spitting, which of course is its consequence. If their theaters had the orchestra of the Feydeau, and a choir of angels to boot, I could find but little pleasure, so long as they were followed by this running accompaniment of thorough base.[15]

Final years

_-_desaturated_version.jpg.webp)

By the late 1830s, blackface acts and Bowery-style melodrama had come to eclipse traditional drama in popularity for New York audiences. Simpson adapted, booking more novelty acts and entertainments that emphasized spectacle over high culture.[16] The patronage changed, as well, as the New York Herald noted:

On Friday night the Park Theatre contained 83 of the most profligate and abandoned women that ever disgraced humanity; they entered in the same door, and for a time mixed indiscriminately with 63 virtuous and respectable ladies. ... Men of New York, take not your wives and daughters to the Park Theatre, until Mr. Simpson pays some respect to them by constructing a separate entrance for the abandoned of the sex.[17]

Nevertheless, the theatre's traditional patronage continued to support it, and the Park largely maintained its high-class reputation.[18]

Edgar Allan Poe wrote a more critical editorial in the Broadway Journal:

The well-trained company of rats at the Park Theatre understand, it is said, their cue perfectly. It is worth the price of admission to see their performance. By long training they know precisely the time when the curtain rises, and the exact degree in which the audience is spellbound by what is going on. At the sound of the bell [signaling the start of the show] they sally out; scouring the pit for chance peanuts and orange-peel. When, by the rhyming couplets, they are made aware that the curtain is about to fall, they disappear—through the intensity of the performers. A profitable engagement might be made, we think, with "the celebrated Dog Bill" [part of William Cole's act in P. T. Barnum's American Museum].[19]

The Park Theatre was finally destroyed by fire on December 16, 1848. The Astor family opted not to rebuild it, the more fashionable clientele having moved north to Washington Square and Fifth Avenue; instead they had stores constructed on the site.

References

Notes

- Barnham:839

- Nagler:522-4

- Nagler:522-4

- Barnham:839

- Henderson:49-52

- Bank:115

- Brown:12

- The Daily Advertiser and the Commercial Advertiser, 31 Jan 1798, quoted in Nagler:423

- Nagler:524

- Nagler:522

- Law, Jonathan, ed. The Methuen Drama Dictionary of the Theatre, p. 23 (2011)

- Henderson:51

- Henderson:49

- Henderson:50

- Trollope:263-4; emphasis in original

- Henderson:51

- "Morning Herald: ..."

- Henderson:52

- Poe's Broadway Journal, 1 November 1845, quoted in Poe:454

Sources

- Banham, Martin, ed. (2000). The Cambridge Guide to Theatre (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0521434378.

- Bank, Rosemarie K. (1997). Theatre Culture in America, 1825-1860. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0521563879.

- Brown, T. Allston (1903). A History of the New York Stage: From the First Performance in 1732 to 1901. Vol. 1. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co.

- Dunlap, William (1833a). History of the American Theatre. Vol. 1. London: Richard Bentley. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- Dunlap, William (1833b). History of the American Theatre. Vol. 2. London: Richard Bentley. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- Fay, Theodore S.; Dakin, James H. (1831). Views in New-York and its environs, from accurate, characteristic & picturesque drawings, taken on the spot, expressly for this work. New York: Peabody & Co.:31-4.

- Henderson, Mary C. (2004). The City and the Theatre: The History of New York Playhouses - A 250 Year Journey from Bowling Green to Times Square (Rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Back Stage Books. ISBN 0823006379.

- Ireland, Joseph N. (1866). Records of the New York Stage, from 1750 to 1860. Vol. 1. New York: T. H. Morrell. ISBN 9780608416915. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- Ireland, Joseph N. (1867). Records of the New York Stage, from 1750 to 1860. Vol. 2. New York: T. H. Morrell. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- "Morning Herald: Ladies of New York Look Well to This Thing". New York Herald. September 18, 1838. Archived at Infotrac: 19th Century U. S. Newspapers.

- Nagler, A. M. (1952). A Source Book in Theatrical History (New Dover ed.). New York: Dover. pp. 521–542. ISBN 0486205150.

- Poe, Edgar Allan (2006). Barger, Andrew (ed.). Entire Tales & Poems of Edgar Allan Poe (1st ed.). Memphis: BottleTree Books. ISBN 0976254182.

- Trollope, Francis Milton (1832). Domestic Manners of the Americans. London: Whittaker, Treacher, & Co.

- "Views in the City of New-York: Park Row" The New-York Mirror, a Repository of Polite Literature and the Arts Vol. 8 No. 5 (1830-08-07), pp. 33–4. Online provider: HathiTrust.