Panagiotis Stamatakis

Panagiotis Stamatakis (Greek: Παναγιώτης Σταµατάκης) (c. 1840[lower-alpha 2]–1885) (sometimes anglicised as Panayotis or Stamatakes) was a Greek archaeologist. He is noted particularly for his role in supervising the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann at Mycenae in 1876, and his role in recording and preserving the archaeological remains at the site.

Panagiotis Stamatakis | |

|---|---|

Παναγιώτης Σταµατάκης | |

The only conjectured photograph of Stamatakis, taken during the excavation of Grave Circle A at Mycenae in 1876.[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Born | c. 1840 Varvitsa, Laconia, Greece |

| Died | March 19, 1885 |

| Occupation | Archaeologist |

| Known for | Excavations around Greece, particularly at Mycenae |

| Title | Ephor General (1884–1885) |

Stamatakis was a leading figure of his day in Greek archaeology, being promoted to the country's highest archaeological office (Ephor General of Antiquities) in 1884. In the wider scholarly community, however, his work and significance was largely forgotten after his death.[lower-alpha 3] Modern reassessment of the excavations at Mycenae, fuelled in large part by the rediscovery in the early 21st century of Stamatakis' notebooks from the site,[6][7] led in turn to a re-evaluation of his importance to the Mycenae excavations and to archaeology more generally: he has been described as "one of the great Greek archaeologists of the nineteenth century".[8]

Life and career

Stamatakis was born in the village of Varvitsa in Laconia. Almost nothing is known of his early life: he certainly had no university education, and appears to have been largely self-taught in archaeology.[9]

In January 1866, he was hired as an assistant to Panagiotis Efstratiadis,[10] the Ephor (overseer) General of Antiquities, and sworn in as a civil servant on 15 July.[11] His first task was to record antiquities held in private collections,[1] to enable the Greek Archaeological Service to gain an understanding of the number and condition of ancient finds unearthed to date.[12]

In 1871, then working as an assistant in the Archaeological Office of the Ministry of Education,[14] Stamatakis was invited by the Archaeological Society of Athens to become a travelling ephor for the society,[lower-alpha 4] known as an "apostle".[1] A major part of his role as an "apostle" was to persuade citizens to surrender illegally-excavated antiquities to the state. His energetic approach to these efforts, later described as "tireless in his work, unyielding in the discharge of his duties and unshakeable in the matters of ethics",[1] led to the establishment of public archaeological collections throughout Greece, and the basis for many future archaeological museums,[1] including those at Sparta,[16] Thebes and Chaeronea.[17]

On 3 March 1875, he assumed the post of ephor of central Greece[18] with the Greek Archaeological Service,[11] which was at that time expanding its ranks to include a number of such officers.[13]

During his career, Stamatakis travelled and excavated widely in Greece. He discovered and excavated a tholos tomb at the site of the Heraion of Argos,[19] and his finds in Argos formed the basis for the early collection of the Archaeological Museum of Argos, opened in 1878.[20] He campaigned in Boeotia against the illegal excavation and trade of antiquities from 1871 onwards,[13] carrying out excavations in 1873–1875 at Tanagra following the illegal looting of the necropolis there in the early 1870s,[21] where the looting of around 10,000 tombs had raised concerns about antiquities looting and smuggling among the Greek press and population.[22] His excavations brought to light various funerary reliefs and inscriptions.[21] He also worked in the Aegean islands, producing the first archaeological maps of Delos and Mykonos.[23] From 1872 to 1873, he stayed on Delos to supervise the excavation of the French School at Athens at the sanctuary of Heracles, directed by J. Albert Lebègue.[24]

Excavations at Mycenae, 1876–1877

Background to the excavations

The German archaeologist and businessman Heinrich Schliemann first visited Mycenae in 1868,[25] and tried unsuccessfully to secure a permit to excavate there throughout the early 1870s. The permit to excavate at the site belonged to the Archaeological Society of Athens,[3] and Schliemann wrote in January 1870 to Stefanos Koumanoudis, secretary of the society, to propose that he excavate the site on their behalf.[26] In this letter, he expressed his belief that the royal tombs of Mycenae might be found within the citadel.[26] However, Schliemann's letter of 26 February 1870 to Frank Calvert indicated that his petition had been unsuccessful.[26] Further events in Greece, particularly the Dilessi murders of April, put paid to any prospect of an official permit that year, and Schliemann left Greece for Troy, where he excavated until 1873.

Throughout his time in Troy, Schliemann continued to push for permission to excavate in Greece. On 16 November 1872, he became a member of the Archaeological Society of Athens,[27] and in January 1873 he made another petition, to Panagiotis Efstratiadis and to Dimitrios Kallifronas, the Minister for Ecclesiastical Affairs and Public Education, which was again refused.[28] Further efforts to offer 'Treasure of Priam', excavated from Troy in May 1873, in exchange for permission, were similarly rebuffed.[29] At first, he divided his attentions between Mycenae and Olympia, but the Greek government awarded the permit for Olympia to the German government early in 1874, to which Schliemann reacted in fury.[30] Between 23 February and 4 March 1874, Schliemann travelled to Mycenae, hired workers and made an illegal excavation, digging 34 test trenches around the site[31] and only stopping when forced to do so by the police, on Kallifronas' and Efstratiadis' orders.[32][33]

In 1874, Dimitrios Voulgaris — famous for the corruption of his governments[34] — became Prime Minister for the eighth and final time. The new government, through Kallifronas' successor Ioannis Valassopoulos, gave Schliemann permission to excavate, but gave ultimate responsibility for the project to the Greek Archaeological Service under Efstratiadis. Efstratiadis in turn stipulated that Stamatakis should serve as supervisor to the project, responsible for ensuring that Schliemann followed the terms of his permit and that the interests of the Greek state in preserving the antiquities were respected.[35]

Schliemann's excavations of 1876

"Mr Schliemann, from the very beginning of the excavations, has shown a tendency to destroy, against my wishes, everything Greek or Roman in order that only what he identifies as Pelasgian houses and tombs remain and be preserved. Whenever pottery sherds of the Greek and Roman period are uncovered, he treats them with disgust. If in the course of the work they fall into his hands, he throws them away. We, however, collect everything – what he calls Pelasgian, and Greek and Roman pieces."

—Stamatakis, August 1874.[36]

Legal troubles prevented Schliemann from beginning the excavations until 28 July 1876.[30] On July 21, Valassopoulos had confirmed Stamatakis as overseer of the excavation, and made clear that it was being treated as an operation of the Archaeological Society of Athens, for whom Schliemann was in effect working.[18]

Stamatakis kept a daily diary of the excavations, and supplemented this with regular reports to his superiors in the Greek government and the Archaeological Society.[37] Among his major contributions to the excavations was establishing the system for classifying finds by material.[37] More generally, he insisted on the meticulous recording of all finds, often clashing with Schliemann's desire to demolish anything that was not "Homeric", and οften slowed or stopped part of the work in order to ensure that finds, such as the relief of the Lion Gate, could be properly assessed and protected.[37] While Schliemann only visited the site, at least at first, in the mornings and evenings, Stamatakis remained throughout the day, supervising the work,[37] and it was he who took charge of the recording, sorting and processing of finds.[38] His efforts and documentation have been credited with preserving the "scientific integrity" of the excavation, and preventing its descent into "gold-digging".[39]

Schliemann's initial excavations took place around the Lion Gate and, when Stamatakis insisted that he stop removing material from around the gate until its structural integrity could be assessed, the Tomb of Clytemnestra. On 27 August, Stamatakis halted the excavations for three days, in protest at the difficulty of supervising Schliemann's rapidly-expanding workforce (now numbering seventy workers, versus thirty in July) and at Schliemann's attempts to remove finds, particularly stelae, from the site.[40] Schliemann's behaviour, however, remained focused on completing the excavations as quickly as possible: he had hired a total of 125 workers by September.[41]

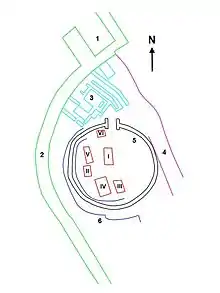

The excavation of Grave Circle A took place over only eleven days.[39] Schliemann discovered five shaft graves within the circuit, conventionally numbered with Roman numerals I–V. Schliemann's recording of this phase of the excavation has been described as having 'serious scientific shortcomings, including the often vague and confusing information he provided on findspots.'[42] Schliemann gave no detailed account of the arrangements of the graves, and what details he did include were frequently incorrect, often adjusting the truth to fit a neater arrangement.[43] Stamatakis, by contrast, maintained a detailed account of the position of each burial and the finds associated with it, and his rediscovered notebooks formed the basis of a major reassessment of the Grave Circle A burials in 2009.[44] In contrast to Schliemann's emphasis on speedily recovering the finds, Stamatakis sought to analyse the material and its stratigraphy fully before removing it: he attempted, for instance, to study the position and emplacement of the stelae above the shaft graves, in order to test a hypothesis that they might have been fixed in the ground considerably later than the burials they marked.[45] In the case of Grave I, Schliemann's failure to record the stratigraphy of the layers above the graves, born out of a desire to excavate as quickly as possible, has been blamed for the destruction of valuable information as to whether Mycenaean figurines, dated around four centuries later than the burials, might have been placed in the grave as offerings during the re-building of Grave Circle A in the Late Mycenaean period.[46]

Relationship with Schliemann

"Mr Schliemann conducts the excavations as he wishes, paying no regard either to the law or to the instructions of the Ministry or to any official. Everywhere and at all times he prefers to look to his own advantage."

—Stamatakis, September 1874.[47]

The relationship between Stamatakis and Schliemann was strained. Schliemann referred to him only once in his 1878 publication of Mycenae, his own monograph on the site and excavations, as 'a government clerk'.[23] In his letters, Schliemann called him "a government spy",[41] and his wife Sophia Schliemann referred to him as "our enemy".[48] In his own letters to his superiors in the Archaeological Society of Athens and the Greek Archaeological Service, Stamatakis twice threatened to resign.[42] When ordered to stop digging or slow down the work, both Heinrich and Sophia could be aggressive: on one occasion, Stamatakis reported to Athens that Heinrich had "began to insult [him] coarsely', and that Sophia had 'abuse[d] [him] in front of the workers, saying that [he] was illiterate and fit only to conduct animals".[41] By early October, Stamatakis and Schliemann were speaking only through intermediaries.[49]

Schliemann left Mycenae on 4 December 1876: in a letter to Max Müller, he wrote that Stamatakis "would have made an excellent executioner",[50] and professed his determination never to excavate in Greece again.[51] Later, in 1877, he described him as "the brute delegate of the Greek government".[52]

No securely-identified image of Stamatakis survives, and it has been suggested that Schliemann had him edited out of an illustration published in Mycenae as a consequence of their poor relationship.[1] After Stamatakis' death, Schliemann referred to him in his monograph Tiryns as a "distinguished archaeologist".[53]

Stamatakis' work at Mycenae after Schliemann's departure

.jpg.webp)

Schliemann left Mycenae on 4 December 1876, with many finds remaining partially exposed in the ground and several trenches unfinished.[54] Stamatakis would continue working at the site until January 1878,[55] aiming both to head off any possibility of looting and to ensure that Schliemann's excavations were properly finished. He was also responsible in this period for the safe transportation of the antiquities found at Mycenae to Athens,[56] where they were stored, against Schliemann's protests, in the basement of the National Bank.[57] At the end of December, it was agreed that they would be moved to a new display in the Polytechneion, which Stamatakis arranged, ordering the finds according to the burials with which they were discovered.[58]

Stamatakis returned to Mycenae early in January 1877.[59] Following the observation of a trench to the south side of the Grave Circle, Stamatakis excavated and discovered, along with Vasilios Drosinos, Schliemann's surveyor,[31] the remains of the so-called "Ramp House", including a treasury of gold vessels, jewellery and a signet ring.[55] This assemblage, known as the "Acropolis Treasure", has been interpreted as the contents of a looted shaft grave.[31] Much of its material was imported, showing connections between Mycenae and Central Europe.[55] Another major project undertaken by Stamatakis in this period was the systematic photography of the finds and remains at Mycenae.[60]

In June 1877,[61] Stamatakis excavated two Mycenaean chamber tombs at Spata near Athens.[62] On 1 November, he returned to Mycenae, and began excavating on the 9th: by the 19th, a sixth Shaft Grave (numbered as VI), containing two burials, was discovered near the entrance to the Grave Circle, and Stamatakis excavated it on that day.[63] In December, he uncovered four further cist graves towards the outside of the Grave Circle.[64]

After Mycenae

In 1879, Stamatakis excavated the burial mound of the Theban 'Sacred Band' on the battlefield of Chaeronea, and in 1882 he began the excavation of the polyandrion of the Thespian warriors who died at the Battle of Delium in 424 BCE.[17] Most of his archaeological work remained unpublished at the time of his death:[1] he also carried out excavations at Delphi, Phthiotis and throughout Greece.

In 1881, he is said to have carried out the clearing of a well on the acropolis of Daulis in Phocis, uncovering a number of Classical vase fragments.[65] In 1882, he invited Christos Tsountas, then aged 25,[66] to accompany him on a tour of Boeotia, combatting the illicit trade in antiquities — an event which has been described as the beginning of Tsountas' 'apprenticeship' to Stamatakis.[67]

In 1884, on the retirement of Panagiotis Efstratiadis,[2] Stamatakis was promoted to Ephor General, the highest office in the Greek Archaeological Service. He died less than a year later, on 19 March 1885, of malaria: contemporary newspapers reported that he had contracted the disease during his excavations at Chaeronea,[11] and he had certainly suffered from it for a number of years.[66] He was buried in the First Cemetery of Athens, in a tomb whose headstone was designed by Wilhelm Dörpfeld, a German architect and archaeologist who had assisted Schliemann with his excavations at Troy. Some time afterwards, however, the tomb was demolished, apparently because Stamatakis lacked any living descendants to whom ownership of it could be passed.[11] However, it has been noted that several surviving 19th-century graves in the First Cemetery belong to people without living heirs, and suggested on that basis that "the municipality of Athens considered the grave to be rather unimportant".[68]

Footnotes

Notes

- The identification is uncertain: it has also been identified as Heinrich Schliemann.[1]

- Stamatakis' precise date of birth is not known: Petrakos approximates it to 1830,[2] Traill gives it as "about 1840",[3] while Stamatakis' contemporary Minos Lappas, who wrote his eulogy, said that he devoted his life to archaeology "from the age of twenty". Since he began working for the Ephor General of Antiquities in 1866, this would support a birth date no later than 1846.[4]

- A 2006 study reassessing his impact on the excavations of Mycenae called him an "underrated and elusive figure".[5]

- Since its foundation in 1834, the Greek Archaeological Service had employed only one member of staff, plus occasional assistants.[15] The Archaeological Society of Athens, formed in 1837, aimed to support the Greek state in matters of antiquities management and protection, but remained (and remains) distinct from the Greek Archaeological Service and the Greek government.[13]

References

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi & Paschalidis 2019, p. 112.

- Petrakos 2011, p. 15.

- Traill 2012, p. 79.

- Petrakos 2005, p. 117.

- Prag et al. 2009, p. 234.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi 2020, pp. 279–280.

- Prag et al. 2009, p. 233.

- Traill 2012, p. 84.

- Traill 2012, p. 205.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi 2020, p. 277.

- Athens Archaeological Society 2019.

- Zachariou 2013, p. 15.

- Petrakos 2007, p. 22.

- Petrakos 2007, p. 23.

- Petrakos 2007, pp. 22–23.

- Raftopoulou 1998, p. 140.

- Archaeological Museum of Thebes 2016.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 79.

- Antonaccio 1992, p. 100.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi 2020, pp. 277–278.

- Marchand 2011, p. 207.

- Galanakis 2011, p. 193–194.

- Prag et al. 2009, p. 235.

- Vasilikou 2006, pp. 17–21.

- Moorehead 2016, p. 145.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 20.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 25.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 29.

- Vasilikou 2011, pp. 29–36.

- Dickinson 1976, p. 161.

- French 2013, p. 20.

- Antoniadis & Kouremenos 2021, p. 187.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 39.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 44.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 53.

- Quoted in Traill 2012, p. 81.

- Traill 2012, p. 80.

- Traill 2012, p. 82.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi 2020, p. 278.

- Traill 2012, pp. 81–82..

- Moorehead 2016, p. 163.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi & Paschalidis 2019, p. 113.

- Dickinson et al. 2012, p. 170.

- Prag et al. 2009.

- Traill 2012, p. 83.

- Dickinson et al. 2012, p. 173.

- Quoted in Traill 2012, p. 82.

- Traill 1989, p. 103.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 107.

- Moorehead 2016, p. 168.

- Dickinson et al. 2012, p. 169.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 131.

- Schliemann 1886, p. liv.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi & Paschalidis 2019, p. 115.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi 2020, p. 283.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 134.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 137.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi & Paschalidis 2019, pp. 117–118.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 141.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 157.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 164.

- Prag et al. 2009, pp. 235–236.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 167.

- Vasilikou 2011, p. 168.

- Wace & Thompson 1912, p. 26.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi & Paschalidis 2019, p. 123.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi 2020, p. 285.

- Antoniadis & Kouremenos 2021, p. 194.

Bibliography

- Antoniadis, Vyron; Kouremenos, Anna (2021). "Selective Memory and the Legacy of Archaeological Figures in Contemporary Athens: The Case of Heinrich Schliemann and Panagiotis Stamatakis". The Historical Review/La Revue Historique. 17: 181–204. doi:10.12681/hr.27071. S2CID 238067293.

- Antonaccio, Carla (1992). "Terraces, Tombs, and the Early Argive Heraion". Hesperia. 61 (1): 85–105. doi:10.2307/148184. JSTOR 148184.

- Archaeological Museum of Thebes (2016). "The scientific work". Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- Athens Archaeological Society (2019). "Stamatakis Panagiotis". Archived from the original on 27 January 2019.

- Dickinson, O.T.P.K.; Papazoglou-Manioudaki, Lena; Nafplioti, Argyro; Prag, A.J.N.W. (2012). "Mycenae Revisited Part 4: Assessing the New Data". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 107: 161–188. doi:10.1017/S0068245412000056. JSTOR 41721882. S2CID 162150714.

- Dickinson, O.T.P.K. (1976). "Schliemann and the Shaft Graves". Greece and Rome. 23 (2): 159–168. doi:10.1017/S0017383500019161. JSTOR 642224. S2CID 162408938.

- French, Elizabeth (2013) [2002]. Mycenae: Agamemnon's Capital. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 9780752419510.

- Galanakis, Yannis (2011). "An unpublished stirrup jar from Athens and the 1871–2 private excavations in the outer Kerameikos". Annual of the British School at Athens. 106: 167–200. doi:10.1017/S0068245411000074. JSTOR 41721707. S2CID 162544324.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi, Eleni; Paschalidis, Constantinos (2019). "The unacknowledged Panayotis Stamatakis and his invaluable contribution to the understanding of Grave Circle A at Mycenae". Archaeological Reports (65): 111–126. JSTOR 26867451.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi, Eleni (2020). "Panagiotis Stamatakis: "Valuing the ancient monuments of Greece as sacred wealth…"". In Lagogianni-Georgakarakos, Maria; Koutsogiannis, Thodoris (eds.). These Are What We Fought For: Antiquities and the Greek War of Independence. Athens: Archaeological Resources Fund. pp. 276–289. ISBN 978-960-386-441-7.

- Marchand, Fabienne (2011). "A New Profession in a Funerary Inscription from Tanagra". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 178: 207–209.

- Moorehead, Caroline (2016). Priam's Gold: Schliemann and the Lost Treasures of Troy. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1-78453-487-5.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2011). Η εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. Οι Αρχαιολόγοι και οι Ανασκαφές 1837–2011 (Κατάλογος Εκθέσεως). Athens.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Petrakos, Vasileios (2007). "The Stages of Greek Archaeology". In Valavanis, Panos (ed.). Great Moments in Greek Archaeology. Athens: Kapon Press. pp. 16–35.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2005). "Η λεηλασία της Τανάγρας και ο Παναγιώτης Σταματάκης". Mentor. 76: 141–150.

- Prag, A.J.N.W.; Papazoglou-Manioudaki, Lena; Neave, R.A.H.; Smith, Denise; Musgrave, J.H.; Nafplioti, A. (2009). "Mycenae Revisited, Part 1: The human remains from Grave Circle A: Stamatakis, Schliemann and two new faces from Shaft Grave VI". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 104: 233–277. doi:10.1017/S0068245400000241. JSTOR 20745367. S2CID 161384796.

- Raftopoulou, Stella (1998). "New Finds from Sparta". British School at Athens Studies. 4: 125–140. JSTOR 40960265.

- Schliemann, Heinrich (1886). Tiryns. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Traill, David (2012). "Schliemann's Mycenae excavations through the eyes of Stamatakis". In Korres, George Styl; Karadimas, Nektarios; Flouda, George (eds.). Archaeology and Heinrich Schliemann. A Century after his Death. Αssessments and Prospects. Myth – History – Science (PDF). Athens. pp. 79–84. ISBN 978-960-93-3929-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Traill, David (1989). "The Archaeological Career of Sophia Schliemann". Antichthon. 23: 99–107. doi:10.1017/S0066477400003725. S2CID 148137252.

- Wace, Alan J.B.; Thompson, Maurice Scott (1912). Prehistoric Thessaly : being some account of recent excavations and explorations in north-eastern Greece from Lake Kopais to the borders of Macedonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vasilikou, Dora (2011). Το χρονικό της ανασκαφής των Μυκηνών, 1870–1878 [The Chronology of the Excavation of Mycenae, 1870–1878] (PDF). Athens: Archaeological Society of Athens. ISBN 978-960-8145-87-0. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- Vasilikou, Dora (2006). Οι ανασκαφές της Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας στις Κυκλάδες 1872–1910. Athens: Archaeological Society of Athens.

- Zachariou, Maria (2013). Looking at the Past of Greece through the Eyes of Greeks (M.A.). University of Virginia.