Pamelaria

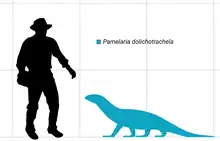

Pamelaria is an extinct genus of allokotosaurian[2] archosauromorph reptile known from a single species, Pamelaria dolichotrachela, from the Middle Triassic of India.[1] Pamelaria has sprawling legs, a long neck, and a pointed skull with nostrils positioned at the very tip of the snout. Among early archosauromorphs, Pamelaria is most similar to Prolacerta from the Early Triassic of South Africa and Antarctica. Both have been placed in the family Prolacertidae. Pamelaria, Prolacerta, and various other Permo-Triassic reptiles such as Protorosaurus and Tanystropheus have often been placed in a group of archosauromorphs called Protorosauria (alternatively called Prolacertiformes), which was regarded as one of the most basal group of archosauromorphs. However, more recent phylogenetic analyses indicate that Pamelaria and Prolacerta are more closely related to Archosauriformes than are Protorosaurus, Tanystropheus, and other protorosaurs, making Protorosauria a polyphyletic grouping.[3]

| Pamelaria Temporal range: Middle Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration of Pamelaria dolichotrachela | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Allokotosauria |

| Family: | †Azendohsauridae |

| Genus: | †Pamelaria Sen, 2003 |

| Type species | |

| †Pamelaria dolichotrachela Sen, 2003[1] | |

A 2015 analysis by Nesbitt et al. found that Pamelaria was the basalmost member of a newly formulated archosauromorph group also containing the Trilophosauridae and the newly redescribed genus Azendohsaurus, which had previously been mistaken for a sauropodomorph dinosaur. This new group was called the Allokotosauria.[2] Later studies generally agreed with Nesbitt et al.'s findings,[4] but some additionally postulated that Pamelaria was more closely related to Azendohsaurus than to trilophosaurids.[5][6]

Description

Based on known specimens, Pamelaria reached a length of about 2 m. The neck, made up of six thick and elongated cervical vertebrae, comprises much of this length. The limbs are robust, roughly equal in size, and sprawl outward from the body. The pectoral girdle is large and plate-like. The tail is thick near its base and narrows closer to its tip.[1]

The skull of Pamelaria is small and pointed with small, conical teeth. The naris (the opening in the bone for the nasal passage) is a single hole positioned at the tip of the snout. The back margin of the skull viewed from above is strongly arched. The orbits or eye sockets are large. The upper temporal fenestrae at the top of the skull are small while the lower temporal fenestrae behind the orbits are quite large. Like those of protorosaurs, the skull of Pamelaria lacks a connection between the quadrate and the jugal bones along the bottom of the skull, meaning that each lower temporal fenestra is not fully enclosed by bone. The lower jaw has a large raised portion in front of the jaw joint called the coronoid process.[1]

Discovery and naming

Fossils of Pamelaria have been found in the Middle Triassic Yerrapalli Formation in Andhra Pradesh, India. The known material represents six individuals from three fossil sites. The most well preserved is a mostly complete and articulated skeleton and is the holotype specimen of Pamelaria. A second partial skeleton belongs to a smaller individual. The other individuals are represented by isolated bones found in association with bones of the archosaur Yarasuchus, Pamelaria was named in 2003 in honor of vertebrate paleontologist Pamela Lamplugh Robinson. The species name dolichotrachela means "long neck" in Greek.[1]

Classification

Pamelaria is a basal member of Archosauromorpha, the clade or evolutionary grouping that includes crocodilians, birds, and all reptiles more closely related to crocodilians and birds than to lizards (which form their own clade, Lepidosauromorpha). Among basal archosauromorphs, Pamelaria is most similar in appearance to Prolacerta from the Early Triassic of South Africa and Antarctica. When Pamelaria was named in 2003, both were placed in the family Prolacertidae. Pamelaria, Prolacerta, and other prolacertids were considered to belong to a diverse group of archosauromorphs called Protorosauria, which also includes the families Protorosauridae and Tanystropheidae. The features that are most often used to classify protorosaurs are long cervical vertebrae and a gap below the lower temporal fenestra of the skull, both of which are found in Pamelaria.[1]

Beginning in 1998, phylogenetic analyses showed that Prolacerta was not closely related to other protorosaurs; it was found to be in a more derived position than protorosaurs, closer the clade Archosauriformes. A 2009 analysis confirmed that this was also the case for Pamelaria. Both Pamelaria and Prolacerta were closely related to Archosauriformes while other protorosaurs formed a clade near the base of Archosauromorpha. The 2009 analysis also found that Prolacertidae was paraphyletic, with Prolacerta being more closely related to archosauriforms than is Pamelaria. This result suggests that features such as a long neck that were once regarded as evidence of a close relationship between Pamelaria and Prolacerta instead evolved independently in both taxa. Below is the cladogram from the 2009 analysis showing the relationships of Pamelaria and other archosauromorphs:[3]

| Archosauromorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nesbitt et al. (2015) found Pamelaria to be the basalmost allokotosaurian.[2]

Paleobiology

Posture

The neck of Pamelaria was probably held above the rest of the body in life. At the base of the neck, the zygapophysial joints between successive vertebrae are angled to allow for dorsoventral or up-and-down movement of the neck. Closer to the skull the joints are angled in such a way that dorsoventral movement would be restricted but lateral or side-to-side movement would be possible. Therefore, Pamelaria would be able to raise and lower its neck from the base and turn its neck along the rest of its length. However, sideways movement would be limited because the cervical vertebrae are thick.[1]

The tail of Pamelaria is thick and heavy, possibly acting as a counterbalance to the long neck. The tail is tall near its base due to high neural arches above the vertebrae and long chevrons below them. Long sacral and caudal ribs restricted lateral movement, making most of the tail inflexible. The shape of the femur (upper leg bone) indicates that Pamelaria had large caudofemoralis muscles that further restricted the tail's movement (caudofemoralis muscles anchor to the base of the tail and insert into the femur).[1]

The equal length of the fore and hindlimbs suggests that Pamelaria was quadrupedal. The limb bones join loosely with the pectoral and pelvic girdles. Their shape indicates that they sprawled outward in life, giving Pamelaria a posture similar to that of lizards. Pamelaria would have rotated its limbs horizontally to move, pushing off from its outermost toe as do living lizards. To support its weight, Pamelaria may have used both its limbs and the base of its tail, possibly raising the rest of its tail while walking (a behavior also seen in some lizards) to reduce friction with the ground.[1]

Diet

The small conical teeth that line the edges of the upper and lower jaws and the surface of the palate suggest that Pamelaria was insectivorous. Insect burrows are common in Yerrapalli Formation, suggesting that insects would have been an abundant food source.[1]

References

- Sen, K. (2003). "Pamelaria dolichotrachela, a new prolacertid reptile from the Middle Triassic of India". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 21 (6): 663–681. Bibcode:2003JAESc..21..663S. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(02)00110-4.

- Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Flynn, John J.; Pritchard, Adam C.; Parrish, J. Michael; Ranivoharimanana, Lovasoa; Wyss, André R. (2015-12-07). "Postcranial Osteology of Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis (?Middle to Upper Triassic, Isalo Group, Madagascar) and its Systematic Position Among Stem Archosaur Reptiles" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 398: 1–126. doi:10.5531/sd.sp.15. hdl:2246/6624. ISSN 0003-0090.

- Gottmann-Quesada, A.; Sander, P.M. (2009). "A redescription of the early archosauromorph Protorosaurus speneri Meyer, 1832, and its phylogenetic relationships". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 287 (4–6): 123–200. doi:10.1127/pala/287/2009/123.

- Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.

- Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2017-08-21). "A new horned and long-necked herbivorous stem-archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 8366. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.8366S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08658-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5567049. PMID 28827583.

- Pritchard, Adam C.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2017-10-01). "A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (10): 170499. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470499P. doi:10.1098/rsos.170499. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5666248. PMID 29134065.