Original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature with a proclivity to sinful conduct in need of regeneration.[1] The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (the story of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden), in a line in Psalm 51:5 ("I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me"),[2] and in Paul's Epistle to the Romans, 5:12-21 ("Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned").[3][1]

The belief began to emerge in the 3rd century, but only became fully formed with the writings of Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD), who was the first author to use the phrase "original sin" (Latin: peccatum originale).[4][5] Influenced by Augustine, the councils of Carthage (411–418 AD) and Orange (529 AD) brought theological speculation about original sin into the official lexicon of the Church.[6]

Protestant reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin equated original sin with concupiscence (or "hurtful desire"), affirming that it persisted even after baptism and completely destroyed freedom to do good, proposing that original sin involved a loss of free will except to sin.[7] The Jansenist movement, which the Roman Catholic Church declared heretical in 1653, also maintained that original sin destroyed freedom of will.[8] Instead, the Catholic Church declares that "Baptism, by imparting the life of Christ's grace, erases original sin and turns a man back towards God, but the consequences for nature, weakened and inclined to evil, persist in man and summon him to spiritual battle",[9] and that "weakened and diminished by Adam's fall, free will is yet not destroyed in the race."[10]

History of the doctrine

Scriptural background and early development

Judaism does not see human nature as irrevocably tainted by some sort of original sin,[11] while for the Apostle Paul Adam's act released a power into the world by which sin and death became the natural lot of mankind.[12] Early Christianity had no specific doctrine of original sin prior to the 4th century.[13] The idea developed incrementally in the writings of the early Church fathers in the centuries after the New Testament was composed.[14] The authors of the Didache, the Shepherd of Hermas, and the Epistle of Barnabas, all from the late 1st or early 2nd centuries, assumed that children were born without sin; Clement of Rome and Ignatius of Antioch, from the same period, took universal sin for granted but did not explain its origin from anywhere; and while Clement of Alexandria in the late 2nd century did propose that sin was inherited from Adam, he did not say how.[15]

The biblical bases for original sin are generally found in the following passages, the first and last of which explain why the sin is described as "original":

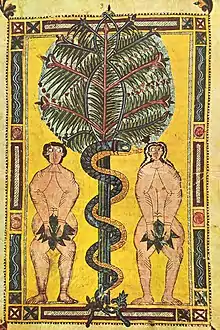

- Genesis 3, the story of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden;[16]

- Psalm 51:5, "I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me";[17]

- Paul's Epistle to the Romans, 5:12–21, "Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned..."[1][18]

Genesis 3, the story of the Garden of Eden, makes no association between sex and the disobedience of Adam and Eve, nor is the serpent associated with Satan, nor are the words "sin," "transgression," "rebellion," or "guilt" mentioned;[19] the words of Psalm 51:5 read: "Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin my mother conceived me", but while the speaker traces their sinfulness to the moment of their conception, there is little to support the idea that it was meant to be applicable to all humanity.[20] While Paul in Romans writes that "through one man (i.e., Adam) sin entered into the world," his meaning is not that God punishes later generations for the deeds of Adam, but that Adam's story is representative for all humanity.[12]

Second Temple Judaism

.JPG.webp)

The first writings to discuss the first sin at the hands of Adam and Eve were early Jewish texts in the Second Temple Period. In these writings, there is no notion that sin is inherent to an individual or that it is transmitted upon conception. Instead, Adam is more largely seen as a heroic figure and the first patriarch. Demeaning discussions of the beginnings of sin draw greater attention to the stories of Cain or the sons of God mentioned in Genesis 6.

Despite the lack of a notion of original sin, by the 1st century, a number of texts did discuss the roles of Adam and Eve as the first to have committed sin. Wisdom of Solomon states that "God created man for incorruption [...] but death entered the world by the envy of the devil" (2:23–24).[21] Ecclesiasticus describes that "Sin began with a woman, and we must all die because of her" (25:24).[22][lower-alpha 1] While this translation suggests a doctrine of original sin, it has also been criticized on precisely those grounds. The notion of the hereditary transmission of sin from Adam was rejected by both 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch in favor of individual responsibility for sin. Despite describing death as having come to all men through Adam, these texts also held to the notion that it is still the individual that is ultimately responsible for committing his own sin and that it is the individual's sin, rather than the sin of Adam and Eve, that God condemns in a person.[23] Ian McFarland argues that it is the context of this Judaism through which Paul's discussions on the fall of Adam are to be better understood.[lower-alpha 1]

Paul

The writings of Paul were extremely important in terms of the development of the doctrine of original sin. Paul uses much of the same language observed in 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch, such as Adam-death associations. Paul also emphasizes the individual human responsibility for their sins when he described the predominance of death over all "because all have sinned" (Romans 5:12).[24][25]

For the first century after the writings of Paul were written, Christians wrote little about the story of the fall or Adam and Eve more broadly. It is only when the writings of authors such as Justin Martyr and Tatian were produced in the second half of the second century onwards that increased discussion on the story of Adam's fall begins to be written.[lower-alpha 1]

Greek Fathers before Augustine

Justin Martyr, a 2nd-century Christian apologist and philosopher, was the first Christian author to discuss the story of Adam's fall after Paul. In Justin's writings, there is no conception of original sin and the fault of sin lies at the hands of the individual who committed it. In his Dialogue with Trypho, Justin wrote "The Christ has suffered to be crucified for the race of men who, since Adam, were fallen to the power of death and were in the error of the serpent, each man committing evil by his own fault" (chapter 86) and "Men [...] were created like God, free from pain and death, provided they obeyed His precepts and were deemed worthy by Him to be called His sons, and yet, like Adam and Eve, brought death upon themselves" (chapter 124).[26] Irenaeus was an early father appealed to by Augustine on the doctrine of original sin,[5] although he did not believe that Adam's sin was as severe as later tradition would hold and he was not wholly clear about its consequences.[27] One recurring theme in Irenaeus is his view that Adam, in his transgression, is essentially a child who merely partook of the tree ahead of his time.[28]

Clement of Alexandria in the late 2nd century did propose that sin was inherited from Adam, but did not say how.[15] Origen of Alexandria had a notion similar to, but not the same as original sin. To Origen, Genesis was largely a story of allegory. On the other hand, he also believed in the pre-existence of the soul, and theorized that individuals are inherently predisposed to committing sin on account of the transgressions committed in their pre-worldly existence.

Origen is the first to quote Romans 5:12–21, rejecting the existence of a sinful state inherited from Adam. To Origen, Adam's sin sets an example that all humanity partakes in, but is not inherently born into. Responding to and rejecting Origen's theories, Methodius of Olympus rejected the pre-existence of the soul and the allegorical interpretation of Genesis, and in the process, was the first to describe the events of Adam's life as the "Fall".[26]

Greek Fathers would come to emphasize the cosmic dimension of the Fall, namely that since Adam, human beings are born into a fallen world, but held fast to belief that man, though fallen, is free.[5] They thus did not teach that human beings are deprived of free will and involved in total depravity, which is one understanding of original sin among the leaders of the Reformation.[29][30] During this period the doctrines of human depravity and the inherently sinful nature of human flesh were taught by Gnostics, and orthodox Christian writers took great pains to counter them.[31][32] Christian apologists insisted that God's future judgment of humanity implied humanity must have the ability to live righteously.[33][34]

Latin Fathers before Augustine

Tertullian, perhaps the first to believe in hereditary transmission of sin, did so on the basis of the traducian theory. He posited to help explain the origins of the soul, which stated that each individual's soul was derived from the soul of their two parents, and therefore, because everyone is ultimately a descendant of Adam through sexual reproduction, the souls of humanity are partly derived from Adam's own soul – the only one directly created by God, and as a sinful soul, the derived souls of humanity, too, are sinful. Cyprian, on the other hand, believed that individuals were born already guilty of sin, and he was the first to link his notion of original guilt with infant baptism. Cyprian writes that the infant is "born has not sinned at all, except that carnally born according to Adam, he has contracted the contagion of the first death from the first nativity." Another text to assert the connection between original sin and infant baptism was the Manichaen Letter to Menoch, although it is of disputed authenticity.[35]

In addition was Cyril of Jerusalem, who thought humans were born free of sin, but he also believed that, as adults, humanity was naturally biased towards sinning. Ambrose accepted the idea of hereditary sin, also linking it, like Cyprian, to infant baptism, but as a shift from earlier proponents of a transmitted sin, he argued that Adam's sin was solely his own fault, in his attempt to attain equality with God, rather than the fault of the devil. One contemporary of Ambrose was Ambrosiaster, the first to introduce a translation of Romans 5:12 that substituted the language of all being in death "because all sinned" to "in him all sinned".

Augustine's primary formulation of original sin was based on a mistranslation of Romans 5:12. This mistranslation would act as the basis for Augustine's complete development of the doctrine of original sin, and Augustine would quote Ambrosiaster as the source.[36] Augustine himself was not able to read Hebrew or Greek and relied on the translations produced by others. Some exegetes still justify the doctrine of original sin based on the wider context of Romans 5:12–21.[37][38]

Hilary of Poitiers did not clearly articulate a concept of original sin, though anticipates the views of Augustine, as he declared that all humanity is implicated in Adam's downfall.[39]

Augustine

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) taught that Adam's sin[lower-alpha 2] is transmitted by concupiscence, or "hurtful desire",[40][41] resulting in humanity becoming a massa damnata (mass of perdition, condemned crowd), with much enfeebled, though not destroyed, freedom of will.[5] When Adam sinned, human nature was thenceforth transformed. He believed that prior to the Fall Adam had both the freedom to sin and not to sin (posse peccare, posse non peccare), but humans have no freedom to choose not to sin (non posse non peccare) after Adam's Fall.[42] Augustine found the original sin inexplicable given the understanding that Adam and Eve were "created with perfect natures" which would fail to explain how the evil desire arose in them in the first place.[43]

Adam and Eve, via sexual reproduction, recreated human nature. Their descendants now live in sin, in the form of concupiscence, a term Augustine used in a metaphysical, not a psychological sense.[lower-alpha 3] Augustine insisted that concupiscence was not "a being" but a "bad quality", the privation of good or a wound.[lower-alpha 4] He admitted that sexual concupiscence (libido) might have been present in the perfect human nature in paradise, and that only later it became disobedient to human will as a result of the first couple's disobedience to God's will in the original sin.[lower-alpha 5] In Augustine's view (termed "Realism"), all of humanity was really present in Adam when he sinned, and therefore all have sinned. Original sin, according to Augustine, consists of the guilt of Adam that all humans inherit. Although earlier Christian authors taught the elements of physical death, moral weakness, and a sin propensity within original sin, Augustine was the first to add the concept of inherited guilt (reatus) from Adam whereby an infant was eternally damned at birth. Augustine held the traditional view that free will was weakened but not destroyed by original sin until he converted in 412 AD to the Stoic view that humanity had no free will except to sin as a result of his anti-Pelagian view of infant baptism.[44]

Augustine articulated his explanation in reaction to his understanding of Pelagianism that would insist that humans have of themselves, without the necessary help of God's grace, the ability to lead a morally good life, thus denying both the importance of baptism and the teaching that God is the giver of all that is good. According to this understanding, the influence of Adam on other humans was merely that of bad example. Augustine held that the effects of Adam's sin are transmitted to his descendants not by example but by the very fact of generation from that ancestor. A wounded nature comes to the soul and body of the new person from their parents, who experience libido (or concupiscence). Augustine's view was that human procreation was the way the transmission was being effected. He did not blame, however, the sexual passion itself, but the spiritual concupiscence present in human nature, soul and body, even after baptismal regeneration.[lower-alpha 6] Christian parents transmit their wounded nature to children, because they give them birth, not the "re-birth".[lower-alpha 7] Augustine used Ciceronian Stoic concept of passions, to interpret Paul's doctrine of universal sin and redemption. In that view, also sexual desire itself as well as other bodily passions were consequence of the original sin, in which pure affections were wounded by vice and became disobedient to human reason and will. As long as they carry a threat to the dominion of reason over the soul they constitute moral evil, but since they do not presuppose consent, one cannot call them sins. Humanity will be liberated from passions, and pure affections will be restored only when all sin has been washed away and ended, that is in the resurrection of the dead.[lower-alpha 8][45]

Augustine believed that unbaptized infants go to hell as a consequence of original sin.[lower-alpha 9][46] The Latin Church Fathers who followed Augustine adopted his position, which became a point of reference for Latin theologians in the Middle Ages.[47] In the later medieval period, some theologians continued to hold Augustine's view. Others held that unbaptized infants suffered no pain at all: unaware of being deprived of the beatific vision, they enjoyed a state of natural, not supernatural happiness. Starting around 1300, unbaptized infants were often said to inhabit the "limbo of infants".[48] The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1261[49] declares: "As regards children who have died without Baptism, the Church can only entrust them to the mercy of God, as she does in her funeral rites for them. Indeed, the great mercy of God who desires that all men should be saved, and Jesus' tenderness toward children, which caused him to say, 'Let the children come to me, do not hinder them',[50] allow us to hope that there is a way of salvation for children who have died without Baptism. All the more urgent is the Church's call not to prevent little children coming to Christ through the gift of holy Baptism." But the theory of Limbo, while it "never entered into the dogmatic definitions of the Magisterium [...] remains [...] a possible theological hypothesis".[51]

Augustine also identified male semen as the means by which original sin was made heritable, leaving only Jesus Christ, conceived without semen, free of the sin passed down from Adam through the sexual act.[52] This sentiment was echoed as late as 1930 by Pope Pius XI in his Casti connubii: "The natural generation of life has become the path of death by which original sin is communicated to the children."[53]

Pelagius' response

The theologian Pelagius reacted thoroughly negatively to Augustine's theory of original sin. Pelagius considered it an insult to God that humans could be born inherently sinful or biased towards sin, and Pelagius believed that the soul was created by God at conception, and therefore could not be imbued with sin as it was solely the product of God's creative agency. Adam did not bring about inherent sin, but he introduced death to the world. Furthermore, Pelagius argued, sin was spread through example rather than hereditary transmission. Pelagius advanced a further argument against the idea of the transmission of sin: since adults are baptized and cleansed of their sin, their children are not capable of inheriting a sin that the parents do not have to begin with.[54]

Cassian

In the works of John Cassian (c. 360–435), Conference XIII recounts how the wise monk Chaeremon, of whom he is writing, responded to puzzlement caused by his own statement that "man even though he strive with all his might for a good result, yet cannot become master of what is good unless he has acquired it simply by the gift of Divine bounty and not by the efforts of his own toil" (chapter 1). In chapter 11, Cassian presents Chaeremon as speaking of the cases of Paul the persecutor and Matthew the publican as difficulties for those who say "the beginning of free will is in our own power", and the cases of Zaccheus and the good thief on the cross as difficulties for those who say "the beginning of our free will is always due to the inspiration of the grace of God", and as concluding: "These two then; viz., the grace of God and free will seem opposed to each other, but really are in harmony, and we gather from the system of goodness that we ought to have both alike, lest if we withdraw one of them from man, we may seem to have broken the rule of the Church's faith: for when God sees us inclined to will what is good, He meets, guides, and strengthens us: for 'At the voice of thy cry, as soon as He shall hear, He will answer thee'; and: 'Call upon Me', He says, 'in the day of tribulation and I will deliver thee, and thou shalt glorify Me'. And again, if He finds that we are unwilling or have grown cold, He stirs our hearts with salutary exhortations, by which a good will is either renewed or formed in us."[55]

Cassian did not accept the idea of total depravity, on which Martin Luther was to insist.[56] He taught that human nature is fallen or depraved, but not totally. Augustine Casiday states that, at the same time, Cassian "baldly asserts that God's grace, not human free will, is responsible for 'everything [that] pertains to salvation' – even faith".[57] Cassian pointed out that people still have moral freedom and one has the option to choose to follow God. Colm Luibhéid says that, according to Cassian, there are cases where the soul makes the first little turn,[58] but in Cassian's view, according to Casiday, any sparks of goodwill that may exist, not directly caused by God, are totally inadequate and only direct divine intervention ensures spiritual progress;[59] and Lauren Pristas says that "for Cassian, salvation is, from beginning to end, the effect of God's grace".[60]

Church reaction

Opposition to Augustine's ideas about original sin, which he had developed in reaction to Pelagianism, arose rapidly.[61] After a long and bitter struggle several councils, especially the Second Council of Orange in 529, confirmed the general principles of Augustine's teaching within Western Christianity.[5] However, while the Western Church condemned Pelagius, it did not endorse Augustine entirely and, while Augustine's authority was accepted, he was interpreted in the light of writers such as Cassian.[62] Some of the followers of Augustine identified original sin with concupiscence[lower-alpha 10] in the psychological sense, but Saint Anselm of Canterbury challenged this identification in the 11th century, defining original sin as "privation of the righteousness that every man ought to possess", thus separating it from concupiscence. In the 12th century the identification of original sin with concupiscence was supported by Peter Lombard and others,[5] but was rejected by the leading theologians in the next century, most notably by Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas distinguished the supernatural gifts of Adam before the fall from what was merely natural, and said that it was the former that were lost, privileges that enabled man to keep his inferior powers in submission to reason and directed to his supernatural end. Even after the fall, man thus kept his natural abilities of reason, will and passions. Rigorous Augustine-inspired views persisted among the Franciscans, though the most prominent Franciscan theologians, such as Duns Scotus and William of Ockham, eliminated the element of concupiscence and identified original sin with the loss of sanctifying grace.

Eastern Christian theology has questioned Western Christianity's ideas on original sin from the outset and does not promote the idea of inherited guilt.[64]

The Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther (1483–1546) asserted that humans inherit Adamic guilt and are in a state of sin from the moment of conception. The second article in Lutheranism's Augsburg Confession presents its doctrine of original sin in summary form:

It is also taught among us that since the fall of Adam all men who are born according to the course of nature are conceived and born in sin. That is, all men are full of evil lust and inclinations from their mothers' wombs and are unable by nature to have true fear of God and true faith in God. Moreover, this inborn sickness and hereditary sin is truly sin and condemns to the eternal wrath of God all those who are not born again through Baptism and the Holy Spirit. Rejected in this connection are the Pelagians and others who deny that original sin is sin, for they hold that natural man is made righteous by his own powers, thus disparaging the sufferings and merit of Christ.[65]

Luther, however, also agreed with the Roman Catholic doctrine of the Immaculate Conception (that Mary was conceived free from original sin) by saying:

[Mary] is full of grace, proclaimed to be entirely without sin. God's grace fills her with everything good and makes her devoid of all evil. God is with her, meaning that all she did or left undone is divine and the action of God in her. Moreover, God guarded and protected her from all that might be hurtful to her.[66]

Protestant Reformer John Calvin (1509–1564) developed a systematic theology of Augustinian Protestantism by interpretation of Augustine of Hippo's notion of original sin. Calvin believed that humans inherit Adamic guilt and are in a state of sin from the moment of conception. This inherently sinful nature (the basis for the Calvinistic doctrine of "total depravity") results in a complete alienation from God and the total inability of humans to achieve reconciliation with God based on their own abilities. Not only do individuals inherit a sinful nature due to Adam's fall, but since he was the federal head and representative of the human race, all whom he represented inherit the guilt of his sin by imputation. Redemption by Jesus Christ is the only remedy.

John Calvin defined original sin in his Institutes of the Christian Religion as follows:

Original sin, therefore, seems to be a hereditary depravity and corruption of our nature, diffused into all parts of the soul, which first makes us liable to God's wrath, then also brings forth in us those works that Scripture calls "works of the flesh" (Gal 5:19). And that is properly what Paul often calls sin. The works that come forth from it – such as adulteries, fornications, thefts, hatreds, murders, carousings – he accordingly calls "fruits of sin" (Gal 5:19–21), although they are also commonly called "sins" in Scripture, and even by Paul himself.[67]

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (1545–1563), while not pronouncing on points disputed among Catholic theologians, condemned the teaching that in baptism the whole of what belongs to the essence of sin is not taken away, but is only cancelled or not imputed, and declared the concupiscence that remains after baptism not truly and properly "sin" in the baptized, but only to be called sin in the sense that it is of sin and inclines to sin.[68]

In 1567, soon after the close of the Council of Trent, Pope Pius V went beyond Trent by sanctioning Aquinas's distinction between nature and supernature in Adam's state before the Fall, condemned the identification of original sin with concupiscence, and approved the view that the unbaptized could have right use of will.[5] The Catholic Encyclopedia refers: "Whilst original sin is effaced by baptism concupiscence still remains in the person baptized; therefore original sin and concupiscence cannot be one and the same thing, as was held by the early Protestants (see Council of Trent, Sess. V, can. v).".[69]

Modern theologians

Søren Kierkegaard, Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr thought that the doctrine of original sin is not necessarily linked to some act of disobedience by the first human beings; rather, the Fall describes every human person's existential situation.[70] Karl Barth rejected the concepts of original guilt and original corruption for being, as he thought, deterministic and undermining human responsibility; instead, he advanced, as noted by Loke, "an alternative conception of Original Sin (Ursünde) which rests upon the idea that God sees, addresses, and treats humanity as a unity on account of the disobedience that is universal."[71] For Barth, Adam did not pass on sin as corruption. In response to Augustine's problem of the inexplicability of original sin, Loke responds that God is not the first cause of evil, rather created libertarian agents who freely choose evil are the first causes of evil.[72]

Denominational views

Roman Catholicism

The Catechism of the Catholic Church says:

By his sin Adam, as the first man, lost the original holiness he had received from God, not only for himself but for all humans.

Adam and Eve transmitted to their descendants human nature wounded by their own first sin and hence deprived of original holiness and justice; this deprivation is called "original sin".

As a result of original sin, human nature is weakened in its powers, subject to ignorance, suffering and the domination of death, and inclined to sin (this inclination is called "concupiscence").[73]

Anselm of Canterbury wrote: "The sin of Adam was one thing but the sin of children at their birth is quite another, the former was the cause, the latter is the effect."[74] In a child original sin is distinct from the fault of Adam, it is one of its effects. The effects of Adam's sin according to the Catholic Encyclopedia are:

- Death and suffering: "One man has transmitted to the whole human race not only the death of the body, which is the punishment of sin, but even sin itself, which is the death of the soul."

- Concupiscence or inclination to sin: baptism erases original sin but the inclination to sin remains.

- The absence of sanctifying grace in the new-born child is also an effect of the first sin, for Adam, having received holiness and justice from God, lost it not only for himself but also for humanity. Baptism confers original sanctifying grace, lost through the Adam's sin, thus eliminating original sin and any personal sin.[69]

The Catholic Church teaches that every human person born on earth is made in the image of God.[75][76] Within man "is both the powerful surge toward the good because we are made in the image of God, and the darker impulses toward evil because of the effects of Original Sin".[77] Furthermore, it explicitly denies that guilt is inherited from anyone, maintaining that instead humanity inherits its own fallen nature. In this it differs from the Calvinist position that each person actually inherits Adam's guilt, and teaches instead that "original sin does not have the character of a personal fault in any of Adam's descendants [...] but the consequences for nature, weakened and inclined to evil, persist in man".[78]

The Catholic Church has always held baptism to be for the remission of sins including the original sin, and, as mentioned in Catechism of the Catholic Church, 403,[79] infants too have traditionally been baptized, though not held guilty of any actual personal sin. The sin that through baptism is remitted for them could only be original sin. Baptism confers original sanctifying grace that erases original sin and any actual personal sin. The first comprehensive theological explanation of this practice of baptizing infants, guilty of no actual personal sin, was given by Augustine of Hippo, not all of whose ideas on original sin have been adopted by the Catholic Church – the church has condemned the interpretation of some of his ideas by certain leaders of the Protestant Reformation.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains that in "yielding to the tempter, Adam and Eve committed a personal sin, but this sin affected the human nature that they would then transmit in a fallen state. [...] Original sin is called "sin" only in an analogical sense: it is a sin 'contracted' and not 'committed' – a state and not an act" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 404).[80] This "state of deprivation of the original holiness and justice [...] transmitted to the descendants of Adam along with human nature" (Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, 76)[81] involves no personal responsibility or personal guilt on their part (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 405). Personal responsibility and guilt were Adam's, who because of his sin, was unable to pass on to his descendants a human nature with the holiness with which it would otherwise have been endowed, in this way implicating them in his sin. The doctrine of original sin thus does not impute the sin of the father to his children, but merely states that they inherit from him a "human nature deprived of original holiness and justice", which is "transmitted by propagation to all mankind".[82]

In the theology of the Catholic Church, original sin is the absence of original holiness and justice into which humans are born, distinct from the actual sins that a person commits. The absence of sanctifying grace or holiness in the new-born child is an effect of the first sin, for Adam, having received holiness and justice from God, lost it not only for himself but also for humanity.[69] This teaching explicitly states that "original sin does not have the character of a personal fault in any of Adam's descendants".[78] In other words, human beings do not bear any "original guilt" from Adam's particular sin, which is his alone. The prevailing view, also held in Eastern Orthodoxy, is that human beings bear no guilt for the sin of Adam. The Catholic Church teaches: "By our first parents' sin, the devil has acquired a certain domination over man, even though man remains free."[83]

The Catholic doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary is that Mary was conceived free from original sin: "the most Blessed Virgin Mary was, from the first moment of her conception, by a singular grace and privilege of almighty God and by virtue of the merits of Jesus Christ, Savior of the human race, preserved immune from all stain of original sin".[84] The doctrine sees her as an exception to the general rule that human beings are not immune from the reality of original sin.

For the Catholic doctrine, Jesus Christ also was born without the original sin, by virtue of the fact that he is God and was incarnated by the Holy Spirit in the womb of the Virgin Mary.

As Mary was conceived without original sin, this statement opens to the fourth Marian dogma of the Assumption of Mary to Heaven in body and soul, according to the unchangeable dogmatic definition publicly proclaimed by Pope Pius XII. The Assumption to Heaven, with no corruption of the body, was made possible by Mary's being born without the original sin, while, according to Aquinas, other persons need to wait for the final resurrection of the flesh in order to get the sanctification of the whole human being.[85]

Post-conciliar developments

Soon after the Second Vatican Council, biblical theologian Herbert Haag raised the question: "Is original sin in Scripture?".[86] According to his exegesis, Genesis 2:25[87] would indicate that Adam and Eve were created from the beginning naked of the divine grace, an originary grace that, then, they would never have had and even less would have lost due to the subsequent events narrated. On the other hand, while supporting a continuity in the Bible about the absence of preternatural gifts (Latin: dona praeternaturalia)[88] with regard to the ophitic event, Haag never makes any reference to the discontinuity of the loss of access to the tree of life. Genesis 2:17[89] states that, if one ate the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, one would surely die, and the adverb indicates that, by avoiding this type of choice, one would have the possibility but not the certainty of accessing to the other tree. Therefore, in 1970 Latin American biblical scholar Carlos Mesters wondered if "Eden [is] golden age or goad to action", protology or eschatology, nostalgia for an idealized past or hope for something that has yet to happen as it is claimed by Revelation 2:7[90] and Revelation 22:2.[91][92]

Some warn against taking Genesis 3 too literally. They take into account that "God had the church in mind before the foundation of the world" (as in Ephesians 1:4)[93][94] as also in 2 Timothy 1:9:[95] "...his own purpose and grace, which was given us in Christ Jesus before the world began."[96] In his 1986 book 'In the Beginning...', Pope Benedict XVI referred to the term "original sin" as "misleading and unprecise".[97] Benedict does not require a literal interpretation of Genesis, or of the origin of evil, but writes: "How was this possible, how did it happen? This remains obscure. [...] Evil remains mysterious. It has been presented in great images, as does chapter 3 of Genesis, with the vision of two trees, of the serpent, of sinful man."[98][99]

Lutheranism

The Lutheran Churches teach that original sin "is a root and fountain-head of all actual sins."[100]

Eastern Christianity

The Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Churches' version of original sin is the view that sin originates with the Devil, "for the devil sins from the beginning (1 John iii. 8)".[101] The Eastern Church never subscribed to Augustine of Hippo's notions of original sin and hereditary guilt. The church does not interpret "original sin" as having anything to do with transmitted guilt but with transmitted mortality. Because Adam sinned, all humanity shares not in his guilt but in the same punishment.[102]

The Eastern Churches accept the teachings of John Cassian, as do Catholic Churches Eastern and Western,[56] in rejecting the doctrine of total depravity, by teaching that human nature is "fallen", that is, depraved, but not totally. Augustine Casiday states that Cassian "baldly asserts that God's grace, not human free will, is responsible for 'everything [that] pertains to salvation' – even faith".[57] Cassian points out that people still have moral freedom and one has the option to choose to follow God. Colm Luibhéid says that according to Cassian, there are cases where the soul makes the first little turn,[58] while Augustine Casiday says that, in Cassian's view, any sparks of goodwill that may exist, not directly caused by God, are totally inadequate and only direct divine intervention ensures spiritual progress.[59] Lauren Pristas says that "for Cassian, salvation is, from beginning to end, the effect of God's grace".[60]

Eastern Christianity accepts the doctrine of ancestral sin: "Original sin is hereditary. It did not remain only Adam and Eve's. As life passes from them to all of their descendants, so does original sin."[103] "As from an infected source there naturally flows an infected stream, so from a father infected with sin, and consequently mortal, there naturally proceeds a posterity infected like him with sin, and like him mortal."[104]

The Orthodox Church in America makes clear the distinction between "fallen nature" and "fallen man" and this is affirmed in the early teaching of the church whose role it is to act as the catalyst that leads to true or inner redemption. Every human person born on this earth bears the image of God undistorted within themselves.[105] In the Eastern Christian understanding, it is explicitly denied that humanity inherited guilt or a fallen nature from anyone; rather, humanity inherits sin's consequences and a fallen environment: "while humanity does bear the consequences of the original, or first, sin, humanity does not bear the personal guilt associated with this sin. Adam and Eve are guilty of their willful action; we bear the consequences, chief of which is death."[106]

The view of Eastern Christianity varies on whether Mary is free of all actual sin or concupiscence. Some Patristic sources imply that she was cleansed from sin at the Annunciation, while the liturgical references are unanimous that she is all-holy from the time of her conception.[107][108]

Anglicanism

The original formularies of the Church of England also continue in the Reformation understanding of original sin. In the Thirty-Nine Articles, Article IX "Of Original or Birth-sin" states:

Original Sin standeth not in the following of Adam, (as the Pelagians do vainly talk); but it is the fault and corruption of the Nature of every man, that naturally is ingendered of the offspring of Adam; whereby man is very far gone from original righteousness, and is of his own nature inclined to evil, so that the flesh lusteth always contrary to the spirit; and therefore in every person born into this world, it deserveth God's wrath and damnation. And this infection of nature doth remain, yea in them that are regenerated; whereby the lust of the flesh, called in the Greek, Φρονεμα σαρκος, which some do expound the wisdom, some sensuality, some the affection, some the desire, of the flesh, is not subject to the Law of God. And although there is no condemnation for them that believe and are baptized, yet the Apostle doth confess, that concupiscence and lust hath of itself the nature of sin.[109]

However, more recent doctrinal statements (e.g. the 1938 report Doctrine in the Church of England) permit a greater variety of understandings of this doctrine. The 1938 report summarizes:

Man is by nature capable of communion with God, and only through such communion can he become what he was created to be. "Original sin" stands for the fact that from a time apparently prior to any responsible act of choice man is lacking in this communion, and if left to his own resources and to the influence of his natural environment cannot attain to his destiny as a child of God.[110]

Methodism

The Methodist Church upholds Article VII in the Articles of Religion in the Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church:

Original sin standeth not in the following of Adam (as the Pelagians do vainly talk), but it is the corruption of the nature of every man, that naturally is engendered of the offspring of Adam, whereby man is very far gone from original righteousness, and of his own nature inclined to evil, and that continually.[111]

Methodist theology teaches that a believer is made free from original sin when they are entirely sanctified:[112]

We believe that entire sanctification is that act of God, subsequent to regeneration, by which believers are made free from original sin, or depravity, and brought into a state of entire devotement to God, and the holy obedience of love made perfect. It is wrought by the baptism with or infilling of the Holy Spirit, and comprehends in one experience the cleansing of the heart from sin and the abiding, indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit, empowering the believer for life and service. Entire sanctification is provided by the blood of Jesus, is wrought instantaneously by grace through faith, preceded by entire consecration; and to this work and state of grace the Holy Spirit bears witness.[112]

Seventh-day Adventism

Seventh-day Adventists believe that humans are inherently sinful due to the fall of Adam,[113] but they do not totally accept the Augustinian/Calvinistic understanding of original sin, taught in terms of original guilt, but hold more to what could be termed the "total depravity" tradition.[114] Seventh-day Adventists have historically preached a doctrine of inherited weakness, but not a doctrine of inherited guilt.[115] According to Augustine and Calvin, humanity inherits not only Adam's depraved nature but also the actual guilt of his transgression, and Adventists look more toward the Wesleyan model.[116]

In part, the Adventist position on original sin reads:

The nature of the penalty for original sin, i.e., Adam's sin, is to be seen as literal, physical, temporal, or actual death – the opposite of life, i.e., the cessation of being. By no stretch of the scriptural facts can death be spiritualised as depravity. God did not punish Adam by making him a sinner. That was Adam's own doing. All die the first death because of Adam's sin regardless of their moral character – children included.[116]

Early Adventist pioneers (such as George Storrs and Uriah Smith) tended to de-emphasise the morally corrupt nature inherited from Adam, while stressing the importance of actual, personal sins committed by the individual. They thought of the "sinful nature" in terms of physical mortality rather than moral depravity.[116] Traditionally, Adventists look at sin in terms of willful transgressions, and believe that Christ triumphed over sin.

Though believing in the concept of inherited sin from Adam, there is no dogmatic Adventist position on original sin.

Jehovah's Witnesses

According to the theology of Jehovah's Witnesses, all humans are born sinners, because of inheriting sin, corruption, and death from Adam. They teach that Adam was originally created perfect and sinless, but with free will; that the Devil, who was originally a perfect angel, but later developed feelings of pride and self-importance, seduced Eve and then, through her, persuaded Adam to disobey God, and to obey the Devil instead, rebelling against God's sovereignty, thereby making themselves sinners, and because of that, transmitting a sinful nature to all of their future offspring.[117][118] Instead of destroying the Devil right away, as well as destroying the disobedient couple, God decided to test the loyalty of the rest of humankind, and to prove that they cannot be independent of God successfully, but are lost without God's laws and standards, and can never bring peace to the earth, and that Satan was a deceiver, murderer, and liar.[119]

Jehovah's Witnesses believe that all humans possess "inherited sin" from the "one man" Adam, and teach that verses such as Romans 5:12–22, Psalm 51:5, Job 14:4, and 1 Corinthians 15:22 show that humanity is born corrupt and dies because of inherited sin and imperfection, and that inherited sin is the reason and cause for sickness and suffering, made worse by the Devil's wicked influence. They believe Jesus is the "second Adam", being the sinless Son of God and the Messiah, and that he came to undo Adamic sin; and that salvation and everlasting life can only be obtained through faith and obedience to the second Adam.[117][118][119][120][121][122] They believe that "sin" is "missing the mark" of God's standard of perfection, and that everyone is born a sinner, due to being the offspring of sinner Adam.[123]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) rejects the doctrine of original sin. The church's second Articles of Faith reads, "We believe that men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam's transgression."[124] The church's founder Joseph Smith taught that humans had an essentially godlike nature, and were not only holy in a premortal state, but had the potential to progress eternally to become like God.[125] Latter-day Saints take this creed-like statement as a rejection of the doctrine of original sin and any notion of inherited sinfulness.[125] Thus, while modern members of the LDS Church will agree that the fall of Adam brought consequences to the world, including the possibility of sin, they generally reject the idea that any culpability is automatically transmitted to Adam and Eve's offspring.[126] Children under the age of eight are regarded as free of all sin and therefore do not require baptism.[127] Children who die prior to age eight are believed to be saved in the highest degree of heaven.[128]

The LDS Church's Book of Moses states that the Lord told Adam that "thy children are conceived in sin".[129] Apostle Bruce R. McConkie stated that this means that the children were "born into a world of sin".[130]

Swedenborgianism

In Swedenborgianism, exegesis of the first 11 chapters of Genesis from The First Church has a view that Adam is not an individual person. Rather, he is a symbolic representation of the "Most Ancient Church", having a more direct contact with heaven than all other successive churches.[131][132] Swedenborg's view of original sin is referred to as "hereditary evil", which passes from generation to generation.[133] It cannot be completely abolished by an individual man, but can be tempered when someone reforms their own life,[134] and are thus held accountable only for their own sins.[135]

Quakerism

Most Quakers (also known as the Religious Society of Friends), including the founder of Quakerism, George Fox, believe in the doctrine of inward light, a doctrine that states that there is "that of God in everyone".[136] This has led to a common belief among many liberal and universalist Quakers affiliated with the Friends General Conference and Britain Yearly Meeting, based on the ideas of Quaker Rufus Jones among others, that rather than being burdened by original sin, human beings are inherently good, and the doctrine of universal reconciliation, that is, that all people will eventually be saved and reconciled with God.

However, this rejection of the doctrine of original sin or the necessity of salvation is not something that most conservative or evangelical Quakers affiliated with Friends United Meeting or Evangelical Friends Church International tend to agree with. Although the more conservative and evangelical Quakers also believe in the doctrine of inward light, they interpret it in a manner consistent with the doctrine of original sin, namely, that people may or may not listen to the voice of God within them and be saved, and people who do not listen will not be saved.

References

Notes

- McFarland 2011, p. 30, n. 5 additionally cites "2 Enoch 41 (cf. 30–2); Apocalypse of Abraham 23–4; 2 Baruch 48:42; 54:15; 56:5–6; and 4 Ezra 3:21–3; 4:30; 7:11–12, 116–18".

- Augustine taught that Adam's sin was both an act of foolishness (insipientia) and of pride and disobedience to God of Adam and Eve. He thought it was a most subtle job to discern what came first: self-centeredness or failure in seeing truth. Augustine wrote to Julian of Eclanum: "Sed si disputatione subtilissima et elimatissima opus est, ut sciamus utrum primos homines insipientia superbos, an insipientes superbia fecerit." (Contra Julianum, V, 4.18; PL 44, 795). This particular sin would not have taken place if Satan had not sown into their senses "the root of evil" (radix Mali): "Nisi radicem mali humanus tunc reciperet sensus" (Contra Julianum, I, 9.42; PL 44, 670)

- Thomas Aquinas explained Augustine's doctrine pointing out that the libido ("concupiscence"), which makes the original sin pass from parents to children, is not a libido actualis, i.e. sexual lust, but libido habitualis, i.e. a wound of the whole of human nature: "Libido quae transmittit peccatum originale in prolem, non est libido actualis, quia dato quod virtute divina concederetur alicui quod nullam inordinatam libidinem in actu generationis sentiret, adhuc transmitteret in prolem originale peccatum. Sed libido illa est intelligenda habitualiter, secundum quod appetitus sensitivus non continetur sub ratione vinculo originalis iustitiae. Et talis libido in omnibus est aequalis". (STh Iª–IIae q. 82 a. 4 ad 3).

- "Non substantialiter manere concupiscentiam, sicut corpus aliquod aut spiritum; sed esse affectionem quamdam malae qualitatis, sicut est languor". (De nuptiis et concupiscentia, I, 25. 28; PL 44, 430; cf. Contra Julianum, VI, 18.53; PL 44, 854; ibid. VI, 19.58; PL 44, 857; ibid., II, 10.33; PL 44, 697; Contra Secundinum Manichaeum, 15; PL 42, 590.

- Augustine wrote to Julian of Eclanum: "Quis enim negat futurum fuisse concubitum, etiamsi peccatum non praecessisset? Sed futurus fuerat, sicut aliis membris, ita etiam genitalibus voluntate motis, non libidine concitatis; aut certe etiam ipsa libidine – ut non vos de illa nimium contristemus – non qualis nunc est, sed ad nutum voluntarium serviente". (Contra Julianum, IV. 11. 57; PL 44, 766). See also his late work: Contra secundam Iuliani responsionem imperfectum opus, II, 42; PL 45,1160; ibid. II, 45; PL 45,1161; ibid., VI, 22; PL 45, 1550–1551. Cf. Schmitt 1983, p. 104

- Sexual desire is, according to bishop of Hippo, only one – though the strongest – of many physical realisations of that spiritual libido: "Cum igitur sint multarum libidines rerum, tamen, cum libido dicitur neque cuius rei libido sit additur, non fere assolet animo occurrere nisi illa, qua obscenae partes corporis excitantur. Haec autem sibi non solum totum corpus nec solum extrinsecus, verum etiam intrinsecus vindicat totumque commovet hominem animi simul affectu cum carnis appetitu coniuncto atque permixto, ut ea voluptas sequatur, qua maior in corporis voluptatibus nulla est; ita ut momento ipso temporis, quo ad eius pervenitur extremum, paene omnis acies et quasi vigilia cogitationis obruatur". (De civitate Dei, XIV, 16; CCL 48, 438–439 [1–10]). See also: Schmitt 1983, p. 97. See also Augustine's: De continentia, 8.21; PL 40, 363; Contra Iulianum VI, 19.60; PL 44, 859; ibid. IV, 14.65, z.2, s. 62; PL 44, 770; De Trinitate, XII, 9. 14; CCL 50, 368 [verse: IX 1–8]; De Genesi contra Manicheos, II, 9.12, s. 60; CSEL 91, 133 [v. 31–35]).

- "Regeneratus quippe non regenerat filios carnis, sed generat; ac per hoc in eos non quod regeneratus, sed quod generatus est, trajicit". (De gratia Christi et de peccato originali, II, 40.45; CSEL 42, 202[23–25]; PL 44, 407.

- Cf. De civitate Dei, ch. IX and XIV; On the Gospel of John, LX (Christ's feelings at the death of Lazarus, Jn 11)

- Infernum, literally "underworld", later identified as limbo.

- In Catholic theology, the meaning of the word "concupiscence" is the movement of the sensitive appetite contrary to the operation of the human reason. The apostle St Paul identifies it with the rebellion of the "flesh" against the "spirit". "Concupiscence stems from the disobedience of the first sin. It unsettles man's moral faculties and, without being in itself an offence, inclines man to commit sins."[63]

Citations

- Vawter 1983, p. 420.

- Psalm 51:5

- Romans 5:12–21

- Patte 2019, p. 892.

- Cross 1966, p. 994.

- Wiley 2002, p. 56.

- Wilson 2018, pp. 157–187.

- Forget 1910.

- Catechism Catholic Church 405

- Council of Trent (Sess. VI, cap. i and v)

- Pies 2000, p. xviii.

- Boring 2012, p. 301.

- Obach 2008, p. 41.

- Wiley 2002, pp. 37–38.

- Wiley 2002, pp. 38–39.

- Genesis 3

- Psalm 51:5

- Romans 5:12–21

- Toews 2013, p. 13.

- Alter 2009, p. 181.

- Wisdom of Solomon 2:23–24

- Ecclesiasticus 25:24

- Toews 2013, pp. 26–32.

- Romans 5:12

- Toews 2013, pp. 38–47.

- Toews 2013, pp. 48–61.

- Wiley 2002, pp. 40–42.

- Bouteneff 2008, p. 79.

- Wallace & Rusk 2011, pp. 255, 258.

- Turner 2004, p. 71.

- Lohse 1966, p. 104.

- Wallace & Rusk 2011, p. 258.

- McGiffert 1932, p. 101.

- Wallace & Rusk 2011, pp. 258–259.

- BeDuhm & Mirecki, The Light and the Darkness: Studies in Manichaeism and Its World, Brill 2020, p. 154

- Toews 2013, pp. 62–72.

- Moo 1996.

- Morris 1988.

- Williams, D. H. (October 2006). "Justification by Faith: a Patristic Doctrine" (PDF). The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 57 (4): 649–667. doi:10.1017/S0022046906008207. S2CID 170253443.

- "Original Sin". Biblical Apologetic Studies. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Nicholson 1842, p. 118.

- Loke, Andrew Ter Ern (2022). Evil, Sin and Christian Theism. Routledge. p. 123.

- Loke, Andrew (2022). Evil, Sin and Christian Theism. London: Routledge. p. 63.

- Wilson 2018, pp. 16–18, 157–159, 269–271, 279–285.

- Brachtendorf 1997, p. 307.

- "Past Roman Catholic statements about Limbo and the destination of unbaptised infants who die?". Religioustolerance.org. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Study by International Theological Commission (19 January 2007), The Hope of Salvation for Infants Who Die Without Being Baptized, 19–21

- Study by International Theological Commission (19 January 2007), The Hope of Salvation for Infants Who Die Without Being Baptized, 22–25

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1261

- Mark 10:14; cf. 1 Timothy 2:4

- Study by International Theological Commission (19 January 2007), The Hope of Salvation for Infants Who Die Without Being Baptized, secondary preliminary paragraph; cf. paragraph 41.

- Stortz 2001, pp. 93–94.

- Obach 2008, p. 43.

- Toews 2013, pp. 73–89.

- Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series II/Volume XI/John Cassian/Conferences of John Cassian, Part II/Conference XIII/Chapter 11 s:Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series II/Volume XI/John Cassian/Conferences of John Cassian, Part II/Conference XIII/Chapter 11

- Elton 1963, p. 136.

- Casiday 2006, p. 103.

- Cassian, John (1985). Conferences. Paulist Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-8091-2694-1.

- Moss 2009, p. 4.

- "Lauren Pristas, The Theological Anthropology of John Cassian". Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- Wallace & Rusk 2011, pp. 284–285.

- González 1987, pp. 58-.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 2515

- McGuckin 2010.

- Theodore G. Tappert, The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1959), 29.

- Luther's Works, American edition, vol. 43, p. 40, ed. H. Lehmann, Fortress, 1968

- John Calvin, The Institutes of the Christian Religion, II.1.8, LCC, 2 vols., trans. Ford Lewis Battles, ed. John T. McNeill (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1960), 251 (p. 217 of CCEL edition). Cf. Institutes of the Christian Religion at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- "Paul III Council of Trent-5". Ewtn.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Harent 1911.

- Loke, Andrew Ter Ern (2022). Evil, Sin and Christian Theism. London: Routledge. p. 124.

- Loke, Andrew Ter Ern (2022). Evil, Sin and Christian Theism. London: Routledge. p. 124.

- Loke, Andrew Ter Ern (2022). Evil, Sin and Christian Theism. London: Routledge. p. 69.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". Vatican.va. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- De conceptu virginali, xxvi

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". Vatican.va. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Man, The Image of God Paperback – Christoph Cardinal Schoenborn : Ignatius Press". Ignatius.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Morality". Usccb.org. 14 August 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church - IntraText". www.vatican.va. 405. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 403

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 404

- Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, 76

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church - IntraText, 404". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Item 407 in section 1.2.1.7.

- Pius IX, Ineffabilis Deus (1854) quoted in Catechism of the Catholic Church, 491

- Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, III, q. 27. a. 2 referenced in Norberto Del Prado (1919). Divus Thomas et bulla dogmatica "Ineffabilis Deus" (in Latin). p. xv. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018 – via archive.org., with imprimatur di Friar Leonardus Lehu, Vic. Magistri Generalis, O.P.

- Haag 1966.

- Genesis 2:25

- Haag 1966, pp. 11, 49–50.

- Genesis 2:17

- Revelation 2:7

- Revelation 22:2

- Mesters 1970.

- Ephesians 1:4

- "The Holy Spirit and the Trinity (Part 1) (Sermon)". www.bibletools.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- 2 Timothy 1:9

- "Before the World Began". Institute for Creation Research. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Ratzinger 1986, p. 72.

- "General Audience of 3 December 2008: Saint Paul (15). The Apostle's teaching on the relation between Adam and Christ | BENEDICT XVI". vatican.va. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Pope ponders original sin, speaks about modern desire for change". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "The Solid Declaration of the Formula of Concord". Book of Concord. 1580. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "The Longer Catechism of The Orthodox, Catholic, Eastern Church • Pravoslavieto.com". www.pravoslavieto.com. question 157. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ""Orthodox view on Immaculate Conception", Antiochian Christian Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand , and the Philippines". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012.

- Stavros Moschos. "Original Sin And Its Consequences". Biserica.org. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "The Longer Catechism of The Orthodox, Catholic, Eastern Church, 168".

- "Do Not Resent, Do Not React, Keep Inner Stillness | Glory to God for All Things". Fatherstephen.wordpress.com. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "St. Augustine & Original Sin".

- Mother Mary and Ware, Kallistos, "The Festal Menaion", p. 47. St. Tikhon's Seminary Press, 1998.

- Cleenewerck 2008, p. 410.

- "The Thirty-Nine Articles". Anglicans Online. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Doctrine in the Church of England, 1938, London: SPCK; p. 64

- The United Methodist Church: The Articles of Religion of the Methodist Church – Article V—Of the Sufficiency of the Holy Scriptures for Salvation Archived 10 July 2012 at archive.today

- "Christian Holiness and Entire Sanctification". Church of the Nazarene Manual 2017–2021. Church of the Nazarene. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- The SDA Bible Commentary, vol. 5, p. 1131.

- Woodrow W. Whidden. "Adventist Theology: The Wesleyan Connection" (PDF). Bibelschule.info. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- E. G. White, Signs of the Times, 29 August 1892

- Gerhard Pfandl. "Some thoughts on Original Sin" (PDF). Biblical Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Jehovah's Witnesses—Proclaimers of God's Kingdom. Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society. 1993. pp. 144–145.

- What Does the Bible Really Teach?. Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society. 2005. p. 32.

- "The Watchtower 1973, page 724" – "Declaration and resolution", The Watchtower, 1 December 1973, p. 724.

- Penton, M.J. (1997). Apocalypse Delayed. University of Toronto Press. pp. 26–29. ISBN 9780802079732.

- "Angels—How They Affect Us". The Watchtower: 7. 15 January 2006.

- ADAM – jw.org. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- Adam's Sin – The Time for True Submission to God – jw.org. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- Articles of Faith 1:2

- Alexander, p. 64.

- Merrill, Byron R. (1992). "Original sin". In Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 1052–1053. ISBN 0-02-879602-0. OCLC 24502140.

- Moroni 8; "Chapter 20: Baptism", Gospel Principles, (Salt Lake City, Utah: LDS Church, 2011) pp. 114–119.

- "Doctrine and Covenants 137". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. verse 10. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- "Moses 6". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. verse 55. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- Bruce R. McConkie (1985), A New Witness for the Articles of Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book) p. 101.

- Swedenborg 1749–56, p. 410.

- Emanuel Swedenborg. Arcana Coelestia, Vol. 1 of 8. Forgotten Books. ISBN 9781606201077. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Swedenborg 1749–56, p. 96, n. 313: "But as to hereditary evil, the case is this. Everyone who commits actual sin thereby induces on himself a nature, and the evil from it is implanted in his children, and becomes hereditary. It thus descends from every parent, from the father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and their ancestors in succession, and is thus multiplied and augmented in each descending posterity, remaining with each person, and being increased in each by his actual sins, and never being dissipated so as to become harmless except in those who are being regenerated by the Lord. Every attentive observer may see evidence of this truth in the fact that the evil inclinations of parents remain visibly in their children, so that one family, and even an entire race, may be thereby distinguished from every other.".

- Swedenborg 1749–56, p. 229, n.719: "There are evils in man [that] must be dispersed while he is being regenerated, that is, which must be loosened and attempered by goods; for no actual and hereditary evil in man can be so dispersed as to be abolished. It still remains implanted; and can only be so far loosened and attempered by goods from the Lord that it does not injure, and does not appear, which is an arcanum hitherto unknown. Actual evils are those that are loosened and attempered, and not hereditary evils; which also is a thing unknown.".

- Swedenborg 1749–56, p. 336, n.966: "It is to be observed that in the other life no one undergoes any punishment and torture on account of his hereditary evil, but only on account of the actual evils [that] he himself has committed.".

- John L. Nickals, ed. (1975). Journal of George Fox. Religious Society of Friends. p. 774. light of Christ, xl, xliii, xliv, 12, 14, 16, 29, 33–5, 60, 64, 76, 80, 88, 92, 115, 117, 135, 143–4, 150, 155, 173, 174–6, 188, 191, 205, 225–6, 234–7, 245, 274–5, 283–4, 294–6, 303–5, 309, 312, 317–335, 339–40, 347–8, 361, 471–2, 496–7, 575, 642

Bibliography

- Alter, Robert (2009). The Book of Psalms. W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393337044.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A discursive commentary on Genesis 1-11. Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567372871.

- Boring, M. Eugene (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664255923.

- Bouteneff, Peter C. (2008). Beginnings: Ancient Christian Readings of the Biblical Creation Narratives. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4412-0183-6.

- Brachtendorf, J. (1997). "Cicero and Augustine on the Passions". Revue des Études Augustiniennes. Paris: Institut d'études augustiniennes. 43 (2): 289–308. doi:10.1484/J.REA.5.104767.

- Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery. Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- Casiday, A. M. C. (2006). Tradition and Theology in St John Cassian. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929718-4.

- Cleenewerck, Laurent (2008). His Broken Body: Understanding and Healing the Schism Between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. Euclid University Press. ISBN 978-0-615-18361-9.

- Collins, C. John (2014). "Adam and Eve in the Old Testament". In Reeves, Michael R. E.; Madueme, Hans (eds.). Adam, the Fall, and Original Sin: Theological, Biblical, and Scientific Perspectives. Baker Academic. ISBN 9781441246417.

- Cross, Frank Leslie (1966). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. OL 5382229M.

- Fox, Robin Lane (2006). The Unauthorized Version: Truth and Fiction in the Bible. London: Penguin. ISBN 9780141022963.

- Kelly, J. N. D. (2000). Early Christian Doctrines (5th rev. ed.). London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-5252-8.

- Elton, Geoffrey Rudolph (1963). Reformation Europe, 1517–1559. Collins. p. 136.

- Forget, Jacques (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- González, Justo L. (1987). A History of Christian Thought. Vol. 2: From Augustine to the Eve of the Reformation. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-17183-5.

- Haag, Herbert (1966). Biblische Schöpfungslehre und kirchliche Erbsündenlehre (in German). Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk. pp. 11, 49-50. English translation: Haag, Herbert (1969). Is original sin in Scripture?. New York: Sheed and Ward. ISBN 9780836202502.

- Harent, S. (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Levison, Jack (1985). "Is Eve to Blame? A Contextual Analysis of Sirach 25: 24". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 47 (4): 617–623. JSTOR 43717056.

- Lohse, Bernhard (1966). A Short History of Christian Doctrine. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0423-4.

- McFarland, Ian A. (2011). In Adam's Fall: A Meditation on the Christian Doctrine of Original Sin. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444351651.

- McGiffert, Arthur C. (1932). A History of Christian Thought. Vol. 1, Early and Eastern. New York; London: C. Scribner's sons.

- McGuckin, John Anthony (2010). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9254-8.

- Mesters, Carlos (1970). Paraíso terrestre: ¿nostalgia o esperanza? (in Portuguese). Bonum. OCLC 981273435. English translation: Mesters, Carlos (1974). Eden, Golden Age Or Goad to Action?. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-0-8028-2317-5.

- Moo, Douglas J. (1996). The Epistle to the Romans. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2317-5.

- Morris, Leon (1988). The Epistle to the Romans. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8834-4103-9.

- Moss, Rodney (May 2009). "Review of Casiday's Tradition and Theology in St. John Cassian" (PDF). Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae. XXXV (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2012.

- Nicholson, William (1842). An Exposition of the Catechism of the Church of England. John Henry Parker.

- Obach, Robert (16 December 2008). The Catholic Church on Marital Intercourse: From St. Paul to Pope John Paul II. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-3089-6.

- Patte, Daniel (2019). "Original Sin". In Daniel Patte (ed.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Christianity, Two Volume Set. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-5326-8943-7.

- Pies, Ronald W. (2000). The Ethics of the Sages: An Interfaith Commentary on Pirkei Avot. Jason Aronson. ISBN 9780765761033.

- Ratzinger, Cardinal Joseph (1986). In the Beginning...'. A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall (PDF). Translated by Boniface Ramsey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- Schmitt, É. (1983). Le mariage chrétien dans l'oeuvre de Saint Augustin. Une théologie baptismale de la vie conjugale. Études Augustiniennes (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stortz, Martha Ellen (2001). "Where or When Was Your Servant Innocent?". In Bunge, Marcia J. (ed.). The Child in Christian Thought. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846938.

- Swedenborg, Emanuel (1749–56). Arcana Coelestia, Vol. 1 of 8. Translated by John F. Potts (2008 Reprint ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60620-107-7.

- Toews, John (2013). The story of original sin. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 9781620323694.

- Trapè, Agostino (1987). S. Agostino, introduzione alla dottrina della grazia. Collana di Studi Agostiniani 4. Vol. I – Natura e Grazia. Roma: Nuova Biblioteca agostiniana. p. 422. ISBN 88-311-3402-7.

- Turner, H. E. W. (2004). The Patristic Doctrine of Redemption: a study of the development of doctrine during the first five centuries (2004 Reprint ed.). Eugene, Or.: Wipf & Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-930-9.

- U.S. Catholic Church (2003). Catechism of the Catholic Church : with modifications from the Editio Typica (2nd ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50819-3.

- Vawter, Bruce (1983). "Original Sin". In Richardson, Alan; Bowden, John (eds.). The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664227487.

- Wallace, A. J.; Rusk, R. D. (2011). Moral Transformation: the original Christian paradigm of salvation. New Zealand: Bridgehead Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4563-8980-2.

- Wiley, Tatha (2002). Original Sin: Origins, Developments, Contemporary Meanings. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4128-9.

- Williams, Patricia A. (2001). Doing Without Adam and Eve: Sociobiology and Original Sin. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451415438.

- Wilson, Kenneth M. (25 May 2018). Augustine's Conversion from Traditional Free Choice to "Non-free Free Will": A Comprehensive Methodology. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-155753-8.

- Woo, B. Hoon (2014). "Is God the Author of Sin?—Jonathan Edwards's Theodicy". Puritan Reformed Journal. 6 (1): 98–123.

See also

External links

- Article "Original Sin" in Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Book of Concord Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Defense of the Augsburg Confession, Article II: Of Original Sin; from an early Protestant perspective, part of the Augsburg Confession.

- Original Sin According To St. Paul by John S. Romanides

- Ancestral Versus Original Sin by Father Antony Hughes, St. Mary Antiochian Orthodox Church, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Original Sin by Michael Bremmer

- Catholic Church

- Council of Trent (17 June 1546). "Canones et Decreta Dogmatica Concilii Tridentini: Fifth Session, Decree concerning Original Sin". at www.ccel.org. Retrieved 1 November 2013.