Operation Bodyguard

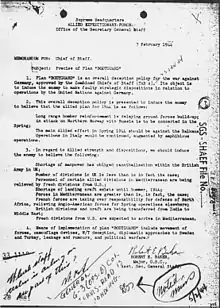

Operation Bodyguard was the code name for a World War II deception strategy employed by the Allied states before the 1944 invasion of northwest Europe. Bodyguard set out an overall stratagem for misleading the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht as to the time and place of the invasion. Planning for Bodyguard was started in 1943 by the London Controlling Section, a department of the war cabinet. They produced a draft strategy, referred to as Plan Jael, which was presented to leaders at the Tehran Conference in late November and, despite skepticism due to the failure of earlier deception strategy, approved on 6 December 1943.

| Operation Bodyguard | |

|---|---|

| Part of Operation Neptune | |

| |

| Type | Military deception |

| Planned | 14 July 1943 – 6 June 1944 |

| Planned by | |

| Objective |

|

| Executed by | Allied states |

| Outcome |

|

Bodyguard was a strategy under which all deception planners would operate. The overall aim was to lead the Germans to believe that an invasion of northwest Europe would come later than was planned and to expect attacks elsewhere, including the Pas-de-Calais, the Balkans, southern France, Norway and Soviet attacks in Bulgaria and northern Norway. The key part of the strategy was to attempt to hide the amount of troop buildup in Southern England, by developing threats across the European theatre, and to emphasise an Allied focus on major bombing campaigns.

The main stratagem was not an operational approach; instead it set out the overall themes for each subordinate operation to support. Deception planners in England and Cairo developed a number of operational implementations (of which the most significant was Operation Fortitude which developed a threat to Pas-de-Calais).

In June 1944 the Allied forces successfully landed and established a beachhead in Normandy. Later evidence demonstrated that German intelligence had believed significant parts of the deceptions, particularly the order of battle for the armies in Southern England. Following the invasion, Hitler delayed redeploying forces from Calais and other regions to defend Normandy for nearly seven weeks (Bodyguard had been intended to delay this for at least 14 days). Evidence suggests that the threat against Pas-de-Calais, and to a lesser extent Norway and Southern Europe, contributed to the German decision.

Background

During World War II, prior to Bodyguard, the Allies made extensive use of deception and developed many new techniques and theories. The main protagonists at this time were 'A' Force, set up in 1940 under Dudley Clarke, and the London Controlling Section, chartered in 1942 under the control of John Bevan.[1][2] German coastal defences were stretched thin in 1944, as they prepared to defend all of the coast of northwest Europe. The Allies had already employed deception operations against the Germans, aided by the capture of all of the German agents in the United Kingdom and the systematic decryption of German Enigma communications. Once Normandy had been chosen as the site of the invasion, it was decided to attempt to deceive the Germans into thinking it was a diversion and that the true invasion was to be elsewhere.

At that stage of the war, Allied and German intelligence operations were heavily mismatched. Through the signals work at Bletchley Park, many of the German lines of communication were compromised since intercepts, codenamed Ultra, gave the Allies insights into how effectively their deceptions were operating. In Europe, the Allies had good intelligence from resistance movements and aerial reconnaissance. By comparison, most of the German spies sent into Britain had been caught or had handed themselves in and turned into double agents (under the XX System). Some of the compromised agents were so trusted that by 1944, German intelligence had stopped sending new infiltrators. Within the German command structure internal politics, suspicion and mismanagement meant intelligence gathering had only limited effectiveness.[3][4]

By 1943, Hitler was defending the entire western coast of Europe, with no clear knowledge of where an Allied invasion might land. His tactic was to defend the entire length and to rely on reinforcements to respond to any landings quickly. In France the Germans deployed two Army Groups. One of them, Army Group B, was deployed to protect the coastline; the Fifteenth Army covering the Pas-de-Calais region and the Seventh Army in Normandy.[5] Following a decision to defer the invasion, Operation Overlord, until 1944, the Allies conducted a series of deceptions intended to threaten invasion in Norway and France. Bodyguard was preceded in late 1943 by Operation Cockade, which was intended to confuse the German high command as to Allied intentions and to draw them into air battles across the Channel. In that respect, Cockade was not a success, with German forces barely responding even as a fake invasion force crossed the channel and turned back some distance from its "target".[6]

Plan Jael

Planning for Bodyguard began even before Operation Cockade was fully under way, following the decision that Normandy would be the site of the coming invasion. The departments responsible for deception, 'A' Force, COSSAC's Ops (B) and the London Controlling Section, began to address the problem of achieving tactical surprise for Overlord. They produced a paper, entitled "First Thoughts", on 14 July 1943 that outlined many of the concepts that would later form the Bodyguard plan. However, since Cockade concluded with limited success, most of the Allied high command were sceptical that any new deception would work.[7][8]

In August, Colonel John Henry Bevan, head of the London Controlling Section, presented a draft plan. Codenamed Jael, a reference to the Old Testament heroine who killed an enemy commander by deception, it would have attempted to deceive the Germans into thinking that the Allies had delayed the invasion for a further year but instead concentrated on the Balkan theatre and on air bombardment of Germany through 1944. The plan had a mixed reception in the Allied High command, and in October, a decision on the draft was deferred until after the Tehran Conference, a month later.[8]

Meanwhile, COSSAC had been working on its own deception strategy, "Appendix Y" of Operation Overlord plan. The plan, also known as Torrent, had originated in early September at COSSAC and started life as a feint invasion of the Calais region shortly before D-Day and eventually, after the failure of a similar scheme during Cockade, transformed into a plan to divert attention from troops building up in the south-west of England.[9] The early ideas, which later became Operation Bodyguard, recognised that the Germans would expect an invasion. Instead, the core of the plan suggested misleading the Germans as to the exact time and location of the invasion and keeping them on the back foot once it had landed.[7]

In November and December 1943, the Allied leaders met twice, first in Cairo (23–27 November) and then in Tehran (28 November–1 December), to decide on strategy for the following year. Bevan attended the conference and received his final orders on 6 December. Furnished with the final details of Overlord, Bevan returned to London to complete the draft. The deception strategy, now codenamed Bodyguard, was approved on Christmas Day 1943. The new name had been chosen based on a comment by Winston Churchill to Joseph Stalin at the Tehran Conference: "In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies".[10][11]

Early 1944 planning

Operation Bodyguard aimed to deceive the enemy as to the timing, weight and direction of the prospective Allied invasion in France. It had three main goals: to make the Pas-de-Calais appear to be the main invasion target, to mask the actual date and time of the assault and to keep German reinforcements in Pas-de-Calais (and other parts of Europe) for at least 14 days after landing.[12]

Bodyguard set out a detailed scenario that the deceivers would attempt to "sell" to the Germans. It included Allied belief in air bombardment as an effective way of winning the war, with the 1944 focus on building bomber fleets. It then specified invasions across the entire European coastline: in Norway, France and the Mediterranean. In January, planners began to fill in the details of Bodyguard, producing the various sub-operations to cover each of the invasions and misdirection.[13]

The task fell to two main departments. 'A' Force, under Dudley Clarke, which had been successful early on, once again took charge of the Mediterranean region. In Europe, however, responsibility shifted away from the LCS, which took on a coordination role. Prior to Dwight Eisenhower's appointment as Supreme Commander, all planning for Overlord fell to the Chief of Staff to the Supreme Commander Allied Forces (COSSAC), Frederick E. Morgan. Under his regime, the deception department, Ops (B), had received limited resources and left most of the planning so far to the London Controlling section. With Eisenhower's arrival, Ops (B) expanded and Dudley Clarke's deputy from 'A' Force, Noel Wild, was placed in control. With the new resources, the department put together the largest single segment of Bodyguard, Operation Fortitude.[13]

Western Front

Bodyguard focused on obfuscating the impending Normandy landings, planned for spring/summer 1944, and so the main effort was focused around the Western front. The planners created Fortitude, building on elements of the earlier Cockade, which encapsulated an entire fictional Allied invasion plan against targets in France and Norway. Its main undertaking was, through the various deception techniques, to overstate the size of the Allied forces in Britain through early 1944, enabling them to threaten multiple targets at once.

Operation Fortitude

Under the Fortitude "story", the Allies intended to invade both Norway and Pas-de-Calais. Using similar techniques to the 1943 Cockade operation (fictional field armies, faked operations, and false "leaked" information) the intention was to increase the apparent size of the Allied forces to make such a large-scale attack seem possible. To allow the plan to stay manageable it was divided into two main sections, each with numerous sub-plans; Fortitude North and South.

Fortitude North was aimed at German forces in Scandinavia and based around the fictional British Fourth Army, based in Edinburgh. The Fourth Army had first been activated the previous year, as part of Cockade to threaten Norway and tie down the enemy divisions stationed there. The Allies created the illusion of the army via fake radio traffic (Operation Skye) and leaks through double agents.[14][15]

Fortitude South employed similar deception in the south of England, threatening an invasion at Pas-de-Calais by the fictional 1st U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) led by U.S. General George Patton. France was the crux of the Bodyguard plan: with Calais as the most logical choice for an invasion, the Allied high command had to mislead the German defences in a very small geographical area. The Pas-de-Calais offered advantages over the chosen invasion site, such as the shortest crossing of the English Channel and the quickest route into Germany. Having a high regard for Patton, German command, particularly Rommel, took steps to heavily fortify that area of coastline. The Allies decided to amplify this belief of a Calais landing.[16]

General Bernard Montgomery, commanding the Allied landing forces, knew that the crucial aspect of any invasion was the ability to grow a beachhead into a full front. He also had only limited divisions at his command, 37 compared to around 60 German formations. Fortitude South's main aims were to give the impression of a much larger invasion force (the FUSAG) in the South-East of England, to achieve tactical surprise in the Normandy landings and, once the invasion had occurred, to mislead the Germans into thinking it was a diversionary tactic with Calais the real objective.[16]

Operation Ironside

While Fortitude represented the major thrust of Bodyguard in support of the Normandy landings, several smaller plans added to the overall picture of confusion. On the Western Front, the largest of them was Operation Ironside. Intercepted communications during January 1944 indicated German high command feared the possibility of landings along the Bay of Biscay, particularly near Bordeaux. The next month, it ordered anti-invasion exercises to be carried out in the region. To play on those fears, the Allies instigated Operation Ironside.[17]

The plot for Ironside was that two divisions sailing from the United Kingdom would land on the Garonne estuary ten days after D-Day. After a beachhead had been established, a further six divisions would arrive directly from the United States. The force would then capture Bordeaux before it linked up with the supposed Operation Vendetta, another deception operation, forces in the south of France.[18][19]

Ironside was implemented entirely via double agents: "Tate", "Bronx" and "Garbo".[17] The Twenty Committee, in charge of anti-espionage and deception operations of British military intelligence, feared the plausibility of the story and so did not promote it too heavily through their agents. Messages sent to their German handlers included elements of uncertainty.[20] That, combined with the fact that Bordeaux was an implausible target (the landing site was far outside the range of fighter cover from the United Kingdom), meant that the Germans took very little notice of the rumours and even went as far as to identify it as a probable deception. However, the Abwehr continued to send questions to their agents related to the landings until early June, and after D-Day, the Germans continued to maintain a state of readiness in the region.[17]

Political pressure

One recurring theme for Bodyguard was the use of political deception. Bevan had concerns over the impact that physical and wireless deception could have. In early 1944, he proposed a wholly political ploy, Operation Graffham, as a way to bolster elements of Bodyguard.[21] Ronald Wingate extended those ideas to create the larger Operation Royal Flush a few months later.[22]

Despite not gaining much traction with the targeted governments, Graffham still influenced the thinking of German commanders and pushed them towards accepting other aspects of Bodyguard.[23]

Royal Flush was, however, less successful, with a report by the Abwehr identifying the targeted countries as "outspoken deception centres". It was the last political overture attempted as part of Bodyguard.[24]

Operation Graffham

Graffham's political target was Sweden, and its main aim was to support the goals of Fortitude North. It was intended to imply that the Allies were building political ties with Sweden in preparation for an upcoming invasion of Norway. The operation involved meetings between several British and Swedish officials as well as the purchase of Norwegian securities and the use of the Double-Cross System to spread false rumours. Sweden maintained a neutral stance during the war, and if its government believed in an imminent Allied invasion of Norway, that would filter through to German intelligence.[21][25][26]

Planning for the operation began in February 1944. Bevan was concerned that Fortitude North was not sufficient in creating a threat against Norway and so he proposed Graffham as an additional measure. In contrast to the other aspects of Bodyguard, the operation was planned and executed by the British, with no American involvement.[21]

Graffham was envisioned as an extension of existing pressure the Allies were placing on Sweden to end its neutral stance, one example being the requests to end the export of ball bearings, an important component in military hardware, to Germany. By increasing that pressure with additional false requests, Bevan hoped to convince the Germans further that Sweden was preparing to join the Allies.[25]

The impact of Graffham was minimal. The Swedish government agreed to few of the concessions requested during the meetings, and few high-level officials were convinced that the Allies would invade Norway. Overall, the influence of Graffham and Fortitude North on German strategy in Scandinavia is disputed.[27][28]

Operation Royal Flush

Royal Flush was proposed and planned by the LCS's Ronald Wingate in April 1944. Building on the approach of Graffham, he hoped to support other Bodyguard deceptions in the Western and Mediterranean theatres by making political overtures to Sweden, Spain and Turkey. The operation continued Graffham's work in Sweden by having ambassadors from the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union demand for the Germans to be denied access to the country after an Allied invasion of Norway.[22][29]

Mediterranean theatre

Overall control of Bodyguard came out of London, local implementation of the Mediterranean portions was left to 'A' Force. By then, Clarke had split the group into several sections, between Egypt and Italy, with responsibility for strategic or tactical deception.[13] From the outset, Bodyguard focused on the Fortitude threat being developed on the Western Front. Deceptions that were planned in the Mediterranean were intended to tie down forces by creating threats to that appeared to have just enough realism.[30]

In late 1943, the Allies had opened a front in Italy, and after the 1944 Normandy landings, focus returned to the Mediterranean as a second front was debated.[31][32] Eventually, deceptions had to be realigned to the Allies' new invasion plans since they, at first, threatened the very place that the earlier operations had suggested as a target.[33][34]

Operation Zeppelin

Zeppelin was the Mediterranean equivalent of Fortitude. It was intended to tie down German forces in the area by threatening landings in the Balkans, particularly Crete or Romania. 'A' Force used similar tactics as before by simulating the existence of the Ninth, Tenth and Twelfth Armies in Egypt via exercises and radio traffic. Although German high command believed that the forces were real, only three under-strength divisions were actually in the area.[30]

Operation Copperhead

Copperhead was a small decoy operation within the scope of Bodyguard that was suggested by Clarke and planned by 'A' Force.[35] The deception, undertaken just prior to D-Day, was intended to mislead German intelligence as to the whereabouts of Bernard Montgomery. It was theorised that as a well-known battle commander, if Montgomery were outside England, that would signal to the Germans that an invasion was not imminent.

The actor M.E. Clifton James, who bore a strong resemblance to the general, made public appearances in Gibraltar and North Africa. The Allies hoped it would indicate a forthcoming invasion via the Mediterranean.

The operation is not known to have made a significant impact. According to captured enemy generals, German intelligence believed that it was Montgomery but still guessed that it was a feint.[36]

Normandy landings

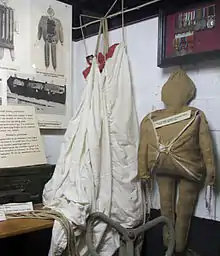

Elements of the Bodyguard plan were in operation on 6 June 1944 in support of Operation Neptune (the amphibious assault of Normandy). Elaborate naval deceptions (Operations Glimmer, Taxable and Big Drum) were undertaken in the English Channel.[37] Small ships and aircraft simulated invasion fleets lying off Pas-de-Calais, Cap d'Antifer and the western flank of the real invasion force.[38] At the same time Operation Titanic involved the RAF dropping fake paratroopers to the east and west of the Normandy landings.

Juan Pujol García, a Spanish double agent working for British intelligence (code named "Garbo") in high standing with the Germans, transmitted information about the Allied invasion plan with a further warning that the Normandy invasion was not a diversion. This information was transmitted at the behest of the British High Command in order to increase his credibility to the Germans and was done at a time when it was too late to fortify Normandy.

Following the landings, some small tactical deceptions were used to add further confusion. Operation Paradise (I–V) established a number of decoy exits and staging areas around the Normandy beaches to draw German attacks.[39]

Deception methods

The Bodyguard deceptions were implemented in several ways, including double agents, radio traffic and visual deception. Once planning for each stage had been completed, various operational units were tasked with carrying out the deceptions. In some cases this could be specialist formations, such as R Force, but in other cases it fell to regular units.

Special means

A large part of the various Bodyguard operations involved the use of double agents. The British "Double Cross" anti-espionage operation had proven very successful from the outset of the war.[40] The LCS was able to use double agents to send back misleading information about Allied invasion plans.[41]

By contrast, Allied intelligence was very good. Ultra, signals intelligence from decrypted German radio transmission, confirmed to planners that the German high command believed in the Bodyguard deceptions and gave them the enemy's order of battle.[42][43]

Visual deception

The practice of using mock tanks and other military hardware had been developed during the North Africa campaign, especially in Operation Bertram for the attack at El Alamein.

For Bodyguard, the Allies put less reliance in those forms of deception since they believed that the German ability to directly reconnoitre England was limited. Some mock hardware was, however, created, particularly dummy landing craft that were stockpiled in the supposed FUSAG staging area.

Aftermath

Operation Bodyguard is regarded as a tactical success, delaying the Fifteenth Army in the Pas-de-Calais for seven weeks thus allowing the Allies to build a beachhead and ultimately win the Battle of Normandy. In his memoirs, General Omar Bradley called Bodyguard the "single biggest hoax of the war".[44]

In his 2004 book, The Deceivers, Thaddeus Holt attributes the success of Fortitude to the trial run of Cockade in 1943: "FORTITUDE in 1944 could not have run as smoothly as it did if the London Controlling Section and its fellows had not gone through the exercise of COCKADE in the year before."[45]

References

- Latimer (2004), pp. 148–149

- Cruickshank (2004)

- Latimer (2001), pp. 207–208

- Holt (2004)

- Latimer 2001, pg 206

- Holt 2004, pp. 478–480

- Holt 2004, pp. 494–496

- Crowdy 2008, pp. 226–228

- Holt 2004, pp. 502–503

- Holt 2004, pp. 504–505

- Cave Brown 1975, pp. 1–10

- Hesketh 2000, p. 12

- Crowdy 2008, pp. 229–230

- Holt 2004, pp. 486

- Cave Brown 1975, pp. 464–466

- Latimer 2001, pp. 218–232

- Holt (2005), pp. 560–561

- Holt (2005), p. 559

- Hesketh (1999), p. 103

- Howard (1990), p. 125

- Barbier (2007), p. 52

- Holt (2005), p. 558

- Barbier (2007), p. 54

- Howard (1990), p. 127

- Levine (2011), p. 219

- Sexton 1983, p. 112

- Barbier (2007), p. 53

- Barbier (2007), p. 185

- Crowdy (2008), p. 289

- Latimer 2001, p. 215

- Holt (2005), p. 620

- Lloyd (2003), p. 93

- Holt (2005), p. 602

- Crowdy (2008), p. 290

- Rankin (2008), p. 178

- Niv by Graham Lord, Orion Books, 2003. P.123

- Barbier (2007), pp. 70–71

- Barbier (2007), pp. 108–109

- Holt (2005), p. 578

- Masterman 1972

- Ambrose 1981, p. 269

- Cave Brown 1975

- Lewin 2001, p. 292

- Latimer 2001, p. 238

- Holt 2004, p. 493

Bibliography

Books

- Barbier, Mary (2007). D-Day Deception: Operation Fortitude and the Normandy Invasion. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0275994792.

- Cave Brown, Anthony (1975). Bodyguard of Lies: The Extraordinary True Story Behind D-Day. London: Comet Book. OCLC 794962630.

- Crowdy, Terry (23 September 2008). Deceiving Hitler: Double Cross and Deception in World War II. Osprey. ISBN 978-1846031359.

- Hesketh, Roger (2000). Fortitude: The D-Day Deception Campaign. Woodstock: The Overlook Press. ISBN 1585670758.

- Holt, Thaddeus (2004). The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0743250427.

- Howard, Michael (1990). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Strategic deception. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521401456.

- Jablonsky, David (1991). Churchill, the Great Game and Total War. Frank Cass. ISBN 0714633674.

- Latimer, John (2001). Deception in War. New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 9781585673810.

- Lewin, Ronald (2001) [1978]. Ultra goes to War (Penguin Classic Military History ed.). London: Penguin Group. ISBN 9780141390420.

- Levine, Joshua (2011). Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII That Saved D-Day. London: HarperCollins UK. ISBN 978-0007413249.

- Lloyd, Mark (2003). The Art of Military Deception. New York: Pen and Sword. ISBN 1473811961.

- Mallmann-Showell, J. P. (2003). German Naval Code Breakers. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 0711028885. OCLC 181448256.

- Masterman, John C. (1972) [1945]. The Double-Cross System in the War of 1939 to 1945. Australian National University Press. ISBN 9780708104590.

- Rankin, Nicholas (2008). Churchill's Wizards: The British Genius for Deception, 1914–1945. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571221950.

Journals

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1981). "Eisenhower, the Intelligence Community, and the D-Day Invasion". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. Wisconsin Historical Society. 64 (4): 261–277. ISSN 0043-6534.

- Sexton, Donal J. (1983). "Phantoms of the North: British Deceptions in Scandinavia, 1941–1944". Military Affairs. Society for Military History. 47 (3): 109–114. doi:10.2307/1988080. ISSN 0026-3931. JSTOR 1988080.

Websites

- Cruickshank, Charles (2004). "Clarke, Dudley Wrangel (1899–1974)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30937. Retrieved 6 December 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)