On Her Majesty's Secret Service (novel)

On Her Majesty's Secret Service is the tenth novel and eleventh book in Ian Fleming's James Bond series, first published in the UK by Jonathan Cape on 1 April 1963. After the relative disappointment of The Spy Who Loved Me, the author made a concerted effort to produce another novel adhering to the tried and tested formula.[1] The initial and secondary print runs sold out, with over 60,000 books sold in the first month, double that of the previous book.[2] Fleming wrote the book in Jamaica whilst the first film in the Eon Productions series of films, Dr. No, was being filmed nearby.

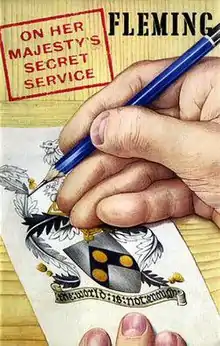

First edition cover, published by Jonathan Cape | |

| Author | Ian Fleming |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping (Jonathan Cape ed.) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 1 April 1963 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 288 |

| Preceded by | The Spy Who Loved Me |

| Followed by | You Only Live Twice |

On Her Majesty's Secret Service is the second book in what is known as the "Blofeld trilogy", which begins with Thunderball and concludes with You Only Live Twice. The story centres on Bond's ongoing search to find Ernst Stavro Blofeld after the Thunderball incident; through contact with the College of Arms in London Bond finds Blofeld based in Switzerland. After meeting him in disguise and discovering his latest plans, Bond attacks the centre where he is based, although Blofeld escapes in the confusion. Bond meets and falls in love with Contessa Teresa "Tracy" di Vicenzo during the story. The pair marry at the end of the story, but hours after the ceremony Blofeld attacks the couple, and kills Tracy.

Fleming made a number of revelations about Bond's character within the book, including showing an emotional side that was not present in the previous stories. In common with Fleming's other Bond stories, he used the names and places of people he knew or had heard of and Blofeld's research station on Piz Gloria was based on Schloss Mittersill, which the Nazis had turned into a research establishment examining the Asiatic races.

On Her Majesty's Secret Service received broadly good reviews in the British and American press. The novel was adapted to run as a three-part story in Playboy in 1963, serialised in the Daily Express newspaper (11 parts) and then developed as a daily cartoon strip in the Daily Express in 1964–1965.[3] In 1969 the novel was adapted as the sixth film in the Eon Productions James Bond film series and was the only film to star George Lazenby as Bond. In 2014 On Her Majesty's Secret Service was adapted as a play on BBC Radio, starring Toby Stephens.

Plot

For more than a year, James Bond, British Secret Service operative 007, has been involved in "Operation Bedlam": trailing the private criminal organisation SPECTRE and its leader, Ernst Stavro Blofeld. The organisation had hijacked two nuclear devices in an attempt to blackmail the western world, as described in Thunderball. Convinced SPECTRE no longer exists, Bond is frustrated by MI6's insistence that he continue the search and his inability to find Blofeld. He composes a letter of resignation for his superior, M.

While composing his letter, Bond encounters a beautiful, suicidal young woman named Contessa Teresa "Tracy" di Vicenzo first on the road and subsequently at the gambling table, where he saves her from a coup de deshonneur by paying the gambling debt she is unable to cover. The following day Bond follows her and interrupts her attempted suicide, but they are captured by professional henchmen. They are taken to the offices of Marc-Ange Draco, head of the Unione Corse, the biggest European crime syndicate. Tracy is the daughter and only child of Draco who believes the only way to save his daughter from further suicide attempts is for Bond to marry her. To facilitate this, he offers Bond a dowry of £1 million (£24 million in 2023 pounds[4]); Bond refuses the offer, but agrees to continue romancing Tracy while her mental health improves.

Afterwards, Draco uses his contacts to inform Bond that Blofeld is somewhere in Switzerland. Bond returns to England to be given another lead: the College of Arms in London has discovered that Blofeld has assumed the title and name of Comte Balthazar de Bleuville, and, wanting formal confirmation of the title, has asked the College to declare him the reigning count.

On a visit to the College of Arms, Bond finds that the family motto of Sir Thomas Bond is "The World Is Not Enough", and that he might be (though unlikely) Bond's ancestor. On the pretext that a genetically-inherited minor physical abnormality (a lack of earlobes) needs a personal confirmation, Bond impersonates a College of Arms representative, Sir Hilary Bray, to visit Blofeld's lair atop Piz Gloria, where he finally meets Blofeld. Blofeld has lost weight and undergone plastic surgery, partly to remove his earlobes, but also to disguise himself from the police and security services who are tracking him down.

Bond learns that Blofeld has apparently been curing a group of young British and Irish women of their livestock and food allergies. In truth, Blofeld and his aide, Irma Bunt, have been brainwashing them into carrying biological warfare agents back to Britain and Ireland in order to destroy the agricultural economy, upon which post-World War II Britain depends. Believing himself discovered, Bond escapes by ski from Piz Gloria, chased by SPECTRE operatives, a number of whom he kills in the process. Afterward, in a state of total exhaustion, he encounters Tracy. She is in the town at the base of the mountain after being told by her father that Bond may be in the vicinity. Bond is too weak to take on Blofeld's henchmen alone and she helps him escape to the airport. Smitten by the resourceful, headstrong woman, he proposes marriage and she accepts. Bond then returns to England and works on the plan to capture Blofeld and thwart his plot.

Helped by Draco's Union Corse, Bond mounts an air assault against the clinic and Blofeld. Whilst the clinic is destroyed, Blofeld escapes down a bobsled run and - although Bond gives chase - Blofeld escapes. Bond flies to Germany where he marries Tracy. The two of them drive off on their honeymoon, but a few hours later, Blofeld and Bunt drive past firing a machine gun. Tracy is murdered in the attack.

Characters and themes

On Her Majesty's Secret Service contains what the author of "continuation" Bond novels Raymond Benson calls "major revelations" about Bond and his character.[5] These start with Bond's showing an emotional side, visiting the grave of Casino Royale's Vesper Lynd, which he did every year.[5] The emotional side continues with Bond asking Tracy to marry him.[6] The character of Tracy is not as well defined as some other female leads in the Bond canon, but Benson points out that it may be the enigmatic quality that Bond falls in love with.[7] Benson also notes that Fleming gives relatively little information about the character, only how Bond reacts to her.[7]

Academic Christoph Lindner identifies the character of Marc-Ange Draco as an example of those characters who have morals closer to those of the traditional villains, but who act on the side of good in support of Bond; others of this type include Darko Kerim (From Russia, with Love), Tiger Tanaka (You Only Live Twice) and Enrico Colombo ("Risico").[8] Fellow academic Jeremy Black noted the connection between Draco and World War II; Draco wears the King's medal for resistance fighters. The war reference is a method used by Fleming to differentiate good from evil and raises a question about "the distinction between criminality and legality", according to Black.[9]

Background

On Her Majesty's Secret Service was written in Jamaica at Fleming's Goldeneye estate in January and February 1962,[10] whilst the first Bond film, Dr. No, was being filmed nearby.[11] The first draft of the novel was 196 pages long and called The Belles of Hell.[12] Fleming later changed the title after being told of a nineteenth-century sailing novel called On Her Majesty's Secret Service, seen by Fleming's friend Nicholas Henderson in Portobello Road Market.[13]

As with all his Bond books, Fleming used events or names from his life in his writing. In the 1930s, Fleming often visited Kitzbühel in Austria to ski; he once deliberately set off down a slope that had been closed because of the danger of an avalanche. The snow cracked behind him and an avalanche came down, catching him at its end: Fleming remembered the incident and it was used for Bond's escape from Piz Gloria.[14] Fleming would occasionally stay at the sports club of Schloss Mittersill in the Austrian Alps; in 1940 the Nazis closed down the club and turned it into a research establishment examining the Asiatic races. It was this pseudo-scientific research centre that inspired Blofeld's own centre of Piz Gloria.[15]

The connection between M and the inspiration for his character, Rear Admiral John Godfrey, was made apparent with Bond visiting Quarterdeck, M's home. He rings the ship's-bell for HMS Repulse, M's last command: it was Godfrey's ship too.[16] Godfrey was Fleming's superior officer in Naval Intelligence Division during the war[17] and was known for his bellicose and irascible temperament.[18] During their Christmas lunch, M tells Bond of an old naval acquaintance, a Chief Gunnery Officer named McLachlan. This was actually an old colleague of both Godfrey and Fleming's in the NID, Donald McLachlan.[11]

The name Hilary Bray was that of an old-Etonian with whom Fleming worked at the stock broking firm Rowe & Pitman,[19] whilst Sable Basilisk was based on "Rouge Dragon" in the College of Arms. Rouge Dragon was the title of heraldic researcher Robin de la Lanne-Mirrlees who asked Fleming not to use the title in the book, although it did appear in the manuscript and typescripts;[20] in a play on words, Fleming used Mirrlees's address, a flat in Basil Street, and combined it with a dragon-like creature, a basilisk, to come up with the name.[21] Mirrlees had Spanish antecedents, generally born without earlobes and Fleming used this physical attribute for Blofeld.[19] Mirrlees also discovered that the line of the Bonds of Peckham bears the family motto "The World is Not Enough", which Fleming appropriated for Bond's own family.[15] Mirrlees also produced the family crest for the character.[1]

Fleming also used historical references for some of his names and Marc-Ange Draco's name is based upon that of El Draco, the Spanish nickname for Sir Francis Drake,[19] a fact also used by J. K. Rowling for the naming of her character Draco Malfoy.[22] For Tracy's background, Fleming used that of Muriel Wright, a married wartime lover of Fleming's, who died in an air-raid,[23] and Bond's grief for the loss of his wife is an echo of Fleming's at the loss of Wright.[24] Fleming did make mistakes in the novel, however, such as Bond ordering a half-bottle of Pol Roger Champagne: Fleming's friend Patrick Leigh Fermor pointed out that Pol Roger was the only champagne at the time not to be produced in half-bottles.[25]

On Her Majesty's Secret Service is the second book in what is called "the Blofeld trilogy", sitting between Thunderball, where SPECTRE is introduced and You Only Live Twice, where Blofeld is finally killed by Bond.[26] Although Blofeld is present in Thunderball, he directs operations from a distance and as such he and Bond never meet and On Her Majesty's Secret Service constitutes his and Bond's first meeting.[5]

Release and reception

On Her Majesty's Secret Service was published on 1 April 1963 in the UK as a hardcover edition by publishers Jonathan Cape;[27] it was 288 pages long and cost 16 shillings.[28] A limited edition of 285 copies was also printed, 250 for sale, being numbered and signed by Fleming, the remainder signed and marked 'For Presentation'.[29] Artist Richard Chopping once again undertook the cover art for the first edition.[27] There were 42,000 advance orders for the hardback first edition[30] and Cape did an immediate second impression of 15,000 copies, selling over 60,000 by the end of April 1963.[31] By the end of 1963 it had sold in excess of 75,000 copies.[32]

The novel was published in America in August by the New American Library,[27] after Fleming changed publishers from Viking Press after The Spy Who Loved Me.[33] The book was 299 pages long and cost $4.50[34] and it topped The New York Times Best Seller list for over six months.[27]

In 2023 Ian Fleming Publications—the company that administers all Fleming's literary works—had the Bond series edited as part of a sensitivity review to remove or reword some racial or ethnic descriptors. The rerelease of the series was for the 70th anniversary of Casino Royale, the first Bond novel.[35]

Reviews

Writing in The Guardian, critic Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing under the name Francis Iles, noted that the two minor grammatical errors he spotted were "likely to spoil no one's enjoyment"[36] of the novel as he considered that On Her Majesty's Secret Service was "not only up to Mr. Fleming's usual level, but perhaps even a bit above it."[36] Writing in The Guardian's sister paper, The Observer, Maurice Richardson pondered if there had been "a deliberate moral reformation"[37] of Bond. However, he notes Bond still has his harder side when needed. Richardson also thought that "in reforming Bond Mr. Fleming has reformed his own story-telling which had been getting very loose".[37] Overall he thought that "O.H.M.S.S. is certainly the best Bond for several books. It is better plotted and retains its insane grip until the end".[37]

Raymond Mortimer, writing for The Sunday Times, said that "James Bond is what every man would like to be, and what every woman would like between her sheets";[15] meanwhile the critic for The Times considered that after The Spy Who Loved Me, "On Her Majesty's Secret Service constitutes a substantial, if not quite a complete, recovery."[28] In the view of the reviewer, it was enough of a recovery for them to point out that "it is time, perhaps, to forget the much exaggerated things which have been said about sex, sadism and snobbery, and return to the simple, indisputable fact that Mr. Fleming is a most compelling story-teller."[28] Marghanita Laski, writing in The Times Literary Supplement, thought that "the new James Bond we've been meeting of late [is] somehow gentler, more sentimental, less dirty."[38] However, she considered that "it really is time to stop treating Ian Fleming as a Significant Portent, and to accept him as a good, if rather vulgar thriller-writer, well suited to his times and to us his readers."[38]

The New York Herald Tribune thought On Her Majesty's Secret Service to be "solid Fleming",[15] while the Houston Chronicle considered the novel to be "Fleming at his urbanely murderous best, a notable chapter in the saga of James Bond".[15] Gene Brackley, writing in the Boston Globe, wrote that Bond "needs all the quality he can muster to escape alive"[39] from Blofeld's clutches in the book and this gives rise to "two of the wildest chase scenes in the good guys-bad guys literature".[39] Regarding the fantastic nature of the plots, Brackley considered that "Fleming's accounts of the half-world of the Secret Service have the ring of authenticity"[39] because of his previous role with the NID.

Writing for The Washington Post, Jerry Doolittle thought that Bond is "still irresistible to women, still handsome in a menacing way, still charming. He has nerves of steel and thews of whipcord",[34] even if "he's starting to look a little older."[34] Doolittle was fulsome in his praise for the novel, saying "Fleming's new book will not disappoint his millions of fans".[34] Writing in The New York Times, Anthony Boucher—described by a Fleming biographer, John Pearson, as "throughout an avid anti-Bond and an anti-Fleming man"[40]—was again damning, although even he admitted that "you can't argue with success".[41] However, he went on to say that "simply pro forma, I must set down my opinion that this is a silly and tedious novel."[41] Boucher went on to bemoan that although On Her Majesty's Secret Service was better than The Spy Who Loved Me, "it is still a lazy and inadequate story",[41] going on to say that "my complaint is not that the adventures of James Bond are bad literature ... but that they aren't good bad literature".[41] Boucher finished his review lamenting that "they just aren't writing bad books like they used to."[41]

The opposite point of view was taken by Robert Kirsch, writing in the Los Angeles Times, who considered Fleming's work to be a significant point in fiction, saying that the Bond novels "are harbingers of a change in emphasis in fiction which is important."[42] The importance, Kirsch claimed, sprung from "a revolution in taste, a return to qualities in fiction which all but submerged in the 20th-century vogue of realism and naturalism"[42] and the importance was such that they were "comparable ... only to the phenomenon of Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories".[42] Kirsch also believed that "with Fleming, ... we do not merely accept the willing suspension of disbelief, we yearn for it, we hunger for it."[42] The critic for Time magazine referred to previous criticism of Fleming and thought that "in Fleming's latest Bond bombshell, there are disquieting signs that he took the critics to heart"[43] when they complained about "the consumer snobbery of his caddish hero".[43] The critic mourned that even worse was to follow, however, when "Bond is threatened with what, for an international cad, would clearly be a fate worse than death: matrimony".[43] However, eventually a "deus ex machina (the machine, reassuringly, is a lethal red Maserati) ... saves James Bond from his better self."[43]

Adaptations

Serialisation (1963)

On Her Majesty's Secret Service was serialised in the April, May and June 1963 issues of Playboy.[44]

On Her Majesty's Secret Service was serialised in the Daily Express, March 18-29 1963.[45]

Comic strip (1964–65)

Ian Fleming's 1963 novel was adapted as a daily comic strip published in the Daily Express newspaper, and syndicated worldwide; the strip ran for nearly a year, from 29 June 1964 to 17 May 1965. The adaptation was written by Henry Gammidge and illustrated by John McLusky.[46] The strip was reprinted by Titan Books in On Her Majesty's Secret Service, published in 2004,[47] and again in The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2, published in 2011.[48]

On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969)

In 1969 the novel was adapted into the sixth film in the Eon Productions series. It starred George Lazenby in his only appearance in the Bond role.[49] With the films being produced in a different order to the books, the continuity of storylines was broken and the films altered accordingly.[50] Even so, the character of Blofeld was present in the previous film, You Only Live Twice, and he and Bond had met: this previous meeting was ignored for the plot of On Her Majesty's Secret Service.[50] The film only made minor changes to the plot.[51]

Radio (2014)

In 2014 the novel was adapted for BBC Radio 4's Saturday Drama strand. Toby Stephens, who played Gustav Graves in Die Another Day, portrayed Bond. Joanna Lumley appeared in both the film and radio adaptations of the novel.[52]

No Time to Die (2021)

Elements of the novel were incorporated into the film No Time to Die, including use of the key phrase, "We have all the time in the world," and themes involving biological warfare.

References

- Gilbert 2012, p. 351.

- Gilbert 2012, p. 332.

- Gilbert 2012, p. 357-8.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Benson 1988, p. 132.

- Benson 1988, p. 133.

- Benson 1988, p. 134.

- Lindner 2009, p. 39.

- Black 2005, p. 59.

- Benson 1988, p. 22.

- Lycett 1996, p. 398.

- Benson 1988, p. 23.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 204.

- Chancellor 2005, pp. 15–16.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 205.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 58.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 192.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 74.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 113.

- Gilbert 2012, p. 352.

- Lycett 1996, p. 404.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 93.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 150.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 155.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 95.

- Benson 1988, p. 131.

- Benson 1988, p. 24.

- "New Fiction". The Times. 4 April 1963. p. 16.

- Gilbert 2012, p. 360-362.

- Lycett 1996, p. 419.

- Lycett 1996, p. 420.

- Lycett 1996, p. 430.

- Lycett 1996, p. 383.

- Doolittle, Jerry (25 August 1963). "007 Seems a Bit Longer in Tooth". The Washington Post. p. G7.

- Simpson, Craig (25 February 2023). "James Bond books edited to remove racist references". The Sunday Telegraph.

- Iles, Francis (3 May 1963). "Criminal Records". The Guardian. p. 8.

- Richardson, Maurice (31 March 1963). "The reformation of Fleming and Bond: On Her Majesty's Secret Service". The Observer. p. 25.

- Laski, Marghanita (5 April 1963). "Strictly for Thrills". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 229.

- Brackley, Gene (22 August 1963). "Cmdr. James Bond Finds the Going Tough". The Boston Globe. p. 19.

- Pearson 1967, p. 99.

- Boucher, Anthony (25 August 1963). "On Assignment with James Bond". The New York Times.

- Kirsch, Robert (25 August 1963). "James Bond Appeal? It's Elementary, Watson". Los Angeles Times. p. E14.

- "Books: Fate Worse than Death". Time. 30 August 1963. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Lindner 2009, p. 92.

- Gilbert 2012, p. 357.

- Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- Gilbert 2012, p. 358.

- McLusky et al. 2011, p. 6.

- Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 82.

- Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 97.

- Vinciguerra, Thomas (27 December 2019). "50 Years Later, This Bond Film Should Finally Get Its Due". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "BBC Radio 4 – Saturday Drama". BBC. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

Bibliography

- Gilbert, Jon (2012). Ian Fleming: The Bibliography. London: Queen Anne Press.

- Pearson, John (1967). The Life of Ian Fleming: Creator of James Bond. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-233-9.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-85286-040-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-85799-783-5.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Smith, Jim; Lavington, Stephen (2002). Bond Films. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0709-4.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Lawrence, Jim; Fleming, Ian; Horak, Yaroslav (2011). The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84856-432-9.

Further reading

- Simpson, Paul (2002). The Rough Guide to James Bond. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-142-5.