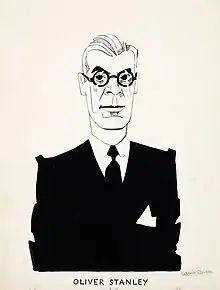

Oliver Stanley

Oliver Frederick George Stanley MC PC MP (4 May 1896 – 10 December 1950) was a prominent British Conservative politician who held many ministerial posts before his relatively early death.

Oliver Stanley | |

|---|---|

Stanley in 1934 | |

| Member of the British Parliament for Bristol West | |

| In office 6 July 1945 – 10 December 1950 | |

| Preceded by | Cyril Culverwell |

| Succeeded by | Sir Walter Monckton |

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | |

| In office 22 November 1942 – 26 July 1945 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Viscount Cranborne |

| Succeeded by | George Hall |

| Secretary of State for War | |

| In office 5 January 1940 – 11 May 1940 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Leslie Hore-Belisha |

| Succeeded by | Anthony Eden |

| President of the Board of Trade | |

| In office 28 May 1937 – 5 January 1940 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Walter Runciman |

| Succeeded by | Sir Andrew Duncan |

| Secretary of State for Transport | |

| In office 22 February 1933 – 29 June 1934 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | John Pybus |

| Succeeded by | Leslie Hore-Belisha |

| Member of the British Parliament for Westmorland | |

| In office 30 October 1924 – 5 July 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Sir John Weston |

| Succeeded by | William Fletcher-Vane |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 May 1896 London, England, UK |

| Died | 10 December 1950 (aged 54) Sulhamstead, Berkshire, England, UK |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse |

Maureen Vane-Tempest-Stewart

(m. 1920; died 1942) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent(s) | Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby Lady Alice Montagu |

| Education | Eton College |

| Profession | Barrister |

Background and education

Stanley was the second son of Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby, by his wife Lady Alice, daughter of William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester. Edward Stanley, Lord Stanley was his elder brother. He was educated at Eton, but did not proceed to the University of Oxford due to the outbreak of World War I.[1][2]

Military career

During the First World War, Stanley was commissioned into the Lancashire Hussars, before transferring to the Royal Field Artillery in 1915. He achieved the rank of captain, and won both the Military Cross and the Croix de Guerre.[1]

Political career

After he was demobilised, Stanley was called to the bar by Gray's Inn in 1919.[1] In the 1924 general election he was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Westmorland. From 1945 he sat for Bristol West.

Ministerial career

He soon came to the attention of the Conservative leaders and held a number of posts in the National Government of the 1930s. As Minister of Transport he was responsible for the introduction of a 30 miles per hour speed limit and driving tests for new drivers. In May 1938 whilst President of the Board of Trade he achieved a rare distinction in British politics when his brother Lord Stanley became Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs – a rare example of two brothers sitting in the same Cabinet, more so as their father, a former Conservative minister, was still alive. Nevertheless, five months later Edward died. (Another example is that of two Labour Party brothers, David Miliband and his brother Ed Miliband, who were appointed to the British Cabinet in June 2007.)

In January 1940 Stanley was appointed Secretary of State for War after the previous incumbent, Leslie Hore-Belisha, had been sacked after falling out with the leading officers. Much was expected of Stanley's tenure in this office, as his father had held it during the First World War, but four months later the government fell and Stanley was replaced by Anthony Eden. Churchill offered Stanley the Dominions Office, which Stanley turned down.[1] Instead, Churchill made Stanley a personal link with intelligence agencies, notably as founder of the London Controlling Section. Two years later Stanley's political fortunes revived when Churchill appointed him Secretary of State for the Colonies, a post which he held until the end of the war.

Last years

After the Conservatives' massive defeat in the 1945 general election Stanley was prominent amongst those rebuilding the party and he came to be regarded as one of the most important Conservative MPs. He was a governor of The Peckham Experiment in 1949.[3] He succeeded his father as Chancellor of the University of Liverpool. By this time, however, his health was in decline; and he died on 10 December 1950 at his home in Sulhamstead.[1]

Had Stanley lived longer, he might well have been appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer when the Conservatives formed a government the following year.[4] Historian Sir Charles Petrie went further, and insisted in his 1972 memoirs (A Historian Looks At His World) that "the greatest blow the Conservative Party has sustained since the late war was the premature death of Oliver Stanley. He was one of the most gifted men of the century, and would have made a very great Prime Minister. ... He was as brilliant a conversationalist as a public speaker."[5]

Family

Stanley married Lady Maureen Vane-Tempest-Stewart, daughter of Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 7th Marquess of Londonderry, and the Hon. Edith Chaplin, in 1920. They had one son and one daughter:

- Michael Charles Stanley (1921–1990), who married (Aileen) Fortune Constance Hugh Smith and had two sons;[6] and

- Kathryn Edith Helen Stanley DCVO (1923–2004), Lady-in-Waiting to Queen Elizabeth II from 1955 to 2002 and who married Sir John Dugdale KCVO (1923–1994) and had two daughters and two sons.[6]

Lady Maureen died in June 1942, aged 41. Stanley survived her by eight years and died in December 1950, aged 54.[6]

References

- Whitfield, Andrew. "Stanley, Oliver Frederick George (1896–1950)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36249. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Stanley, Rt Hon. Oliver Frederick George, (1896–10 Dec. 1950), PC 1934; MP (C) Bristol West since 1945; Chancellor of Liverpool University since 1948". WHO'S WHO & WHO WAS WHO. 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u232113. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- "The Bulletin of the Pioneer Health Centre". Peckham. 1 (5). September 1949. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Howard 1987, p. 178-9

- Petrie, Sir Charles (1972). A Historian Looks at His World. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. pp. 193. ISBN 978-0283978500.

- Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage. Vol. 3 (107th ed.). Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke's Peerage. doi:10.5118/bpbk.2003. ISBN 978-0-9711966-2-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Books cited

- Howard, Anthony RAB: The Life of R. A. Butler, Jonathan Cape 1987 ISBN 978-0224018623

_(2022).svg.png.webp)