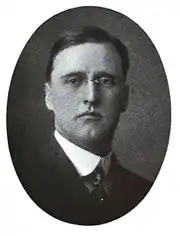

Olaf Swenson

Olaf Swenson ( December 16, 1883 – August 23, 1938) was a Seattle-based fur trader and adventurer active in Siberia and Alaska in the first third of the 20th century. His career intersected with activities of notable explorers of the period, and with the Russian Civil War. He is credited with leading the rescue of the Karluk survivors from Wrangel Island in 1914. According to historian Thomas C. Owen, Swenson's "practicality and zest for adventure made him an ideal entrepreneur on the arctic frontier..."[1]

Born and raised in Michigan, Swenson first reached the far north as a Nome prospector in 1901. The next year he signed on for a prospecting venture in Siberia, spending two summers and one winter on the Chukchi Peninsula. He returned to Siberia in 1905, this time with his wife and their infant son. His introduction to trading came when their ship was wrecked and he contracted to salvage cargo on a share basis. He continued to trade at Anadyr until 1911. In 1913, Swenson and C.L. Hibbard of Seattle formed the Hibbard-Swenson Company which operated trading schooners and steamers on the Siberian coast, buying furs and ivory and trading a variety of general merchandise until 1921. Swenson continued this business as Olaf Swenson & Co. until 1923 when the Bolshevik victory led to seizure of his business. Two years of negotiations led to a contract with the Soviet government to supply goods on a cost-plus basis and buy furs. This arrangement persisted through 1930. The difficulties of getting furs and personnel out of the Siberian Arctic led to the first commercial flights across the Bering Strait. The fourth such flight crashed in a Siberian winter storm, killing aviation pioneer Carl Ben Eielson and his mechanic in 1929. Swenson's memoir Northwest of the World contains observations on commerce, conditions, and native life in northeast Siberia and won critical praise for its direct style and vivid description.

Early life

Olaf Swenson was born in Manistee, Michigan, the second son of Nils and Amelia (née Peterson or Petersen) Swenson. Nils was a Swedish emigrant and at that time a prosperous hotel and saloon keeper. Amelia died in childbirth when Olaf was six years old, and the baby died shortly afterward. Another sister died accidentally in childhood. Nils never remarried, and the two boys were raised in the home of their grandparents, Ole and Sophie Petersen.[2][n 1]

Prospecting for gold in Alaska and Siberia

Nils and Olaf went to Nome, Alaska, in 1901 to prospect for gold. Finding little success, they signed on to help work a claim on shares. This was a paying proposition but nobody got rich, and Olaf and his father returned to Seattle for the winter. The next spring they returned to Nome and signed on for a prospecting expedition to the Chukchi Peninsula of northeastern Siberia sponsored by the Northeastern Siberian Company, Limited. They spent two summers and one winter in Siberia, mostly on the Arctic coast, but found no exploitable gold and returned to Seattle in the fall of 1903. Returning Northeastern Siberian Company prospectors reported promising signs including colors in every stream panned and graphite deposits. Some still thought exploitable placer gold would eventually be found. However, the Deseret News quoted Nels [sic] and Olaf Swenson as expecting that the wealth would come from [gold-bearing] quartz deposits.[4]

Family

After returning from Siberia, Swenson worked in Seattle for American Biscuit Company for a year and a half.[5] In May 1904 he married Emma Charlotte Johnson in Seattle. Charlotte, as she preferred to be known, had immigrated from Sweden in 1903.[6] They had at least one son and two daughters. Their son died in Nome in 1910 of diphtheria contracted on board ship from Seattle.[7] Their daughter Marion was born about 1912 and Marjorie (sometimes spelled Marguery or Margery) about 1918.[8]

Trading in the Anadyr region of Siberia

In 1905, Swenson set out on another prospecting expedition for the Northeastern Siberian Company, this time bringing along his wife and their six-month-old son. In Hanford's account, Swenson was the organizer and by implication the leader of this expedition. Their ship, the gasoline schooner Barbara Hernster, struck a reef near Providence Bay, Siberia, July 28, 1905, and the family reached shore by boat through heavy surf. The ship was subsequently refloated and beached, and Swenson contracted to salvage the cargo in exchange for a share. Subsequently the group and their cargo were picked up and transported to Anadyr,[n 2] where Swenson set up a trading station selling the salvaged supplies. These found a ready market, since the Russo-Japanese War had disrupted normal supply channels.[10]

Swenson is sometimes credited with the first discovery of gold in northeastern Siberia; he credits a group of prospectors headed by Luke Nadeau, part of the same expedition he was on. Swenson was dispatched to Nome with $8,000 worth of gold in 1906. His family went with him. Swenson returned to Anadyr with more trade goods while Charlotte and their son returned "to civilization".[11]

Swenson's trading station of this period is described as lying on St. Nicholas Bay (not named on modern maps), 12 miles (19 km) from Russian Spit (Russkaya Koshka, the northern spit delimiting the outer Anadyr estuary) and 8 miles (13 km) from mountains. Since there are no mountains sufficiently close on the south side of the estuary and no nearby bays north of the estuary, this puts the likely location on the northern mainland shore of the estuary.[12] Swenson (though he does not explicitly say so) was trading under the Northeastern Siberian Company concession.[13] In 1908 the steamer Corwin landed freight and miners at the Northeastern Siberian Company's trading station on the north shore of Anadyr Bay; the current from the river was strong at this location.[14]

Swenson traveled by dogsled at least as far as Cape Navarin and Korfa Bay to trade.[15] Trade goods were packed in parcels of roughly uniform value, sized to fit on Chukchi sleds. Swenson also brought some American-style retail practices including premiums and credit sales. The credit extended to trappers could take the form of both operating supplies and household goods against next year's fur harvest or a later delivery. Swenson spent alternate winters in Anadyr through 1910-1911.[16]

1910 was a year of transition for the Northeastern Siberian Company. The Russian government declined to renew its concession, its president resigned, and it was absorbed by a Russian-French partnership.[1] Swenson went into a Montana cattle ranching venture with his father in 1911, but the venture did not last long; Olaf did not like ranching much, and when his father died in 1912 he sold the ranch. Swenson made a short trading voyage to the Siberian coast in a chartered schooner in 1911 and a longer trip in 1912 in the motor schooner Polar Bear. This second voyage was a partnership with the Hibbard-Stewart company of Seattle and Captain L.L. Lane.[17]

Business of the Hibbard-Swenson and Olaf Swenson companies

Hibbard-Swenson Company

This partnership was formed in 1913 with the purchase of the steam bark Belvedere (formerly an arctic whaler) and lasted through 1921. It eventually expanded to include multiple ships trading from the Sea of Okhotsk to the north coast of Siberia.[18]

Operations

The Hibbard-Swenson company bought furs, whalebone, and walrus and mammoth ivory for cash as well as barter; furs included squirrel, ermine, sable, red fox, white fox, cross fox, wolf, wolverine, deer, hair seal, brown bear, and polar bear. The pattern of the trade was to spend the winter purchasing and packaging trade goods. April through August was spent picking up furs on the Siberian coast. The fall included walrus hunting and sometimes whaling, and miscellaneous shipping with stops in Alaska and Siberia. Turnover was about $1 million per year in the early 1920s.[19][20]

Operations in Kamchatka are described by Sten Bergman, who was in Kamchatka 1920-1922: "Klutchi....is the seat of the Kamchatkan fur trade, and several fur-trading firms have their depots here. The biggest of them are the Hudson's Bay Company and the Olaf Swenson Company — the latter is the concern of a Swedish American of that name. His name is known and esteemed in every dwelling throughout the entire peninsula. Every spring Swenson comes over from Seattle with his steamer, which is laden with everything imaginable that Kamchatka can stand in need of."[21]

Swenson described financing local agents prior to the Bolshevik victory: "It had been our custom to pick out a local spot, put a good man in charge there, and finance him against the business he would do for us, letting him operate in his own name and extend credit according to his own judgment."[22] According to a Soviet source, Swenson had 16 personal agents and provided financing to an additional 14 independent traders, with a total annual turnover in excess of $1 million.[23]

In the period before the Bolshevik victory, trade goods included "foodstuffs, canned milk, canned fruit, clothing of every kind (including frilly things for women), hardware of all kinds, toys for children, a great many luxuries which many of them had never known before." Trade goods mentioned at other locations in Swenson's narrative include flour, wieners (in barrels), oranges, sugar, tea, tobacco, pilot bread, eggs, calico, dishes, needles, thread, knives, pots, pans, chamber pots, firearms and ammunition, motor launches, gasoline, kerosene, Mackinaws and other waterproof clothing, boots, caps, heavy woolen clothing, and corduroy breeches with lacings on the legs. Customers included Russians as well as natives.[24] Alcohol is not mentioned in his lists of trade goods. [n 3]

Impact of the Russian Revolution and civil war

In June 1920, the New York Times reported that Bolshevik partisans had attacked, seized, and looted the Anadyr post of the Hibbard-Swenson Company the preceding January. The leader of the Anadyr Bolsheviks was misidentified as a Seattle seaman named Mikoff, possibly a confusion of the Bolshevik leader Montikoff and a German-American seaman Walter Ahrns who was also involved. According to a report collected in 1922 by Lieutenant John Marie Creighton, USN, from Swenson's local manager John Lampe, the store was seized but not looted and was eventually reclaimed, though not before Lampe found it necessary to flee temporarily. Lampe also managed to maintain a position of neutrality between the first Revcom headed by Montickoff and the group of traders who violently deposed it. (For a synopsis of events as reported by Soviet sources, see P. Gray.)[26]

For a brief period in 1921 and 1922, the White forces were resurgent in the Russian Far East and maintained a tenuous control along the coast. This development had its advantages and its disadvantages. As Swenson put it, Kamchatka was "full of Russians who had come up with the Whites" and they all wanted American clothing and gear. However, "the revolution didn't care much about the importance of the fur traffic and was constantly getting in our way."[27] At one point Swenson's ship was required to evacuate ninety White troops, disarmed at Swenson's insistence, from Okhotsk to Ola.[28] This period also let Swenson get to know several White officers including Colonels Bochkarev [Swenson writes Bochkarov] and Fielkovsky at Gizhiga.[29] Some of these associations would cause him trouble later.

Hibbard-Swenson Company dissolved early in 1922. C.L. Hibbard withdrew from Asian ventures, but Swenson wanted to continue. He formed Olaf Swenson & Company in March 1922 to take over the assets and trading network. Backers included Bryner & Company of Vladivostok, a major trading house in the Russian Far East, Denbigh and Company of Japan and Vladivostok, which had interests in Kamchatka fishing, and other Russian firms. Swenson was President and Treasurer.[30]

The Red Army took Vladivostok in October 1922, and the Soviet government began to consolidate its control of the Northeast. In early 1923 the Soviets seized four trading schooners at East Cape, Siberia, including one owned by Olaf Swenson & Company (the Blue Sea) and one chartered to Swenson, on charges of trafficking alcohol. (The New York Times article suggested that competition with the Hudson's Bay Company could have been a factor, since that company's country manager was the brother of the Soviet governor). Swenson does not discuss this seizure or charge specifically.[31] Later that year the Yakut Revolt was suppressed and the last organized White force under Anatoly Pepelyayev was defeated at Ayan (a port village on the Sea of Okhotsk) on June 17, 1923. In October 1923, G.G. Suddock, Agent for Olaf Swenson Co. at Ayan, arriving in Seattle from Ayan by way of Japan, confirmed to a reporter for the Prescott (AZ) Evening Courier that the Bolshevik victory was complete and there was no more White resistance.[32]

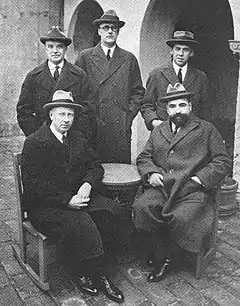

Adapting to the Bolshevik victory

With the Bolshevik victory, Swenson found not just two schooners but his entire Siberian business and stock impounded and a warrant out for his arrest. The issues besides alcohol (if that was really an issue) were taxes and his perceived close association with the Whites. He briefly discusses allegations of selling guns to the Whites, suggesting they were inflated, and attributes some allegations to disgruntled competitors. (Hunting arms and ammunition were a regular part of his business.) He does not mention an allegation of a check for $500,000 found in the pocket of an executed White officer. Swenson reports he declined an offer from a former White officer to raid the coast and recover the furs by force. Instead he and R.S. Pollister (Vice President of Olaf Swenson & Co.) went to China to obtain a Soviet visa and began a long slow process of negotiation to release the furs, trading stock, and books. The ultimate resolution was a contract entered in 1925 to deliver goods in Siberia to Moscow's specification on a cost-plus basis and export furs. This contract was renewed for five years in 1926 and expanded in 1928 after negotiations with the head of the Soviet fur trust in London. Other associates in this venture were Maurice Cantor and Irving W. Herskovits of New York. In this period, the business name often appears as Swenson Trading Company or Swenson Fur Trading Company. Local trade was handled by a Soviet government trading organization which specified the goods and set fur prices. Swenson reports prices paid to the trappers were reduced in this period and the range of trade goods narrowed to necessities.[33]

The contract appears not to have been renewed after 1930. Swenson spent time in Russia in 1931, 1932, and 1933 settling accounts, attending fur sales, and winding up affairs.[34]

Shipping losses

The companies operated multiple vessels at various times. This list of losses may be incomplete.

Belvedere

This former whaler, the company's first ship, sank off the Russian coast, September 16, 1919. The ship was forced into ice near shore by a storm and holed or crushed. All 30 crew and 3 passengers survived.

Kolyma

This power schooner was stranded and wrecked on Sledge Island July 22, 1920, driven ashore in a storm after having left Nome to take shelter in the lea of the island. The vessel was a total loss. All the crew reached safety.

Kamchatka

The Hibbard-Swenson Company diesel auxiliary schooner Kamchatka (formerly the whaling bark Thrasher) was lost to fire in the Bering Sea April 14, 1921. The crew, including Swenson, escaped without loss of life and reached Alaska in a motor launch and a whaleboat. They had no water and subsisted on wieners and oranges from the cargo, running the launch's engine on distillate due to a lack of gasoline.[35][36]

The office of Hibbard-Swenson company's Japanese affiliate was destroyed by fire the same night the Kamchatka was lost.[37]

Elisif

The Elisif, captained by Edwin Larson, was frozen in on the Arctic coast during the winter 1928-9. Resupplied by the Nanuk, she attempted to reach Kolyma with R.S. Pollister aboard as supercargo and A.P. Jochimsen as ice pilot. The ship was punctured by floating ice and beached to prevent sinking. The ship's company evacuated in boats. They initially reached Uelen and planned to wait there for pickup. However a fierce storm came up and when they tried to move their boats to a safer location, they were unable to land again. They made for Little Diomede Island, landed there, and were picked up by the Coast Guard cutter Northland and taken to Nome.[38][39]

Involvement with the Canadian Arctic Expedition

Icebound ships and a trek with news

Belvedere, with Stephen Cottle as her captain and Olaf Swenson on board, became stuck in the ice off the north coast of Alaska in the fall of 1913 while carrying supplies for Vilhjalmur Stefansson's Canadian Arctic Expedition to the transfer point at Herschel Island. The expedition ship Karluk was frozen in about 25 miles (40 km) offshore and subsequently was carried away by moving ice. The whaler Elvira under Captain C.T. Pedersen was frozen in, damaged by the ice and further damaged in a storm, requiring her crew to transfer to the Belvedere. Swenson and Pedersen (accompanied by Enuk, a north-slope Iñupiaq, and later also by Peter, an Indian from the Chandlar lake area) traveled to Circle City and then Fairbanks by foot and dogsled to carry news and arrange relief supplies. They left Icy Reef October 21 and reached Fairbanks November 15, covering an estimated distance of 630 miles (1,010 km). Their route initially took them up the Kongakut River.[n 4] They lost their compass in deep snow during a storm and thereafter navigated by topography alone, adding considerable distance to their planned route. They eventually crossed over the divide, reaching what they believed to be the head of the Salmon River. From there they went overland to Chandlar Lake, and thence to Fort Yukon and Circle by old trails. The final leg to Fairbanks used the Government winter mail trail.[40][41]

Karluk rescue 1914

In 1914 Hibbard-Swenson Company chartered the newly built motor schooner King & Winge to carry relief supplies to the Belvedere and complete the normal trading run. King & Winge became stuck in the ice near Point Barrow and bent her propeller. The ship was extricated by the revenue cutter Bear on August 22. They met the Belvedere at Point Barrow, delivered the supplies, took on some crewmen from the Elvira, and subsequently put into at Nome August 30. Bear arrived the same day and reported that its attempt to rescue the crew of the Karluk from Wrangel Island off the northeast Siberian coast had been thwarted by bad weather, ice and low fuel. Stefansson's former secretary Burt McConnell then requested that King & Winge attempt a rescue; this request was reiterated by Captain Bartlett of the Karluk. Swenson set out for Wrangel Island in the King & Winge with A.P. Jochimsen as Master. They stopped at East Cape, Siberia, and picked up an umiak and a party of natives to man it, in case they had to cross ice interspersed with open water. As they approached the beach in the umiak, the native crew was alarmed to see one of the Karluk survivors vigorously pumping a rifle, but Swenson reassured them in their language. They removed a total of twelve expedition survivors from two separate camps. The survivors included an Inupiaq couple and their two children. The survivors were later transferred to the Bear.[42]

The H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest gives a somewhat different account, with Swenson returning to Seattle and C.L. Hibbard on the King & Winge with Jochimsen. McCurdy's does not list sources; the origin of this account is unknown. It conflicts with both contemporary and later sources listed for the preceding paragraph.[43]

North Cape to Irkutsk trek 1928-9

In the fall of 1928, Swenson was frozen in off North Cape, Siberia (now Cape Schmidt) in the M.S. Elisif. Impatient to get back to Seattle and hungry for adventure, Swenson decided on an overland trek to Irkutsk, which was served by the Trans-Siberian Railway.[38][44]

The first stage employed dogsleds, leaving North Cape October 19, 1928. The route proceeded along the coast, cutting inland on either side of Chaunskaya Bay, to the Kolyma River. Then the party went up the river to Srednekolymsk,[n 5] arriving December 4. They left Srednekolmysk cutting west overland on an old Government trail through flat, forested country dotted by lakes. They switched from dogsleds to reindeer sleds at a village he records as Solgutter.[48]

Much of the ensuing leg of the trip employed an established relay network of reindeer teams and drivers. They crossed the Indigirka River at Zashiversk and then proceeded through Abbi (this is presumably Abyy but if so they seem to have taken a circuitous route) to reach Verkhoyansk January 6, 1929. Heading south for Yakutsk, they were asked to carry the mail; this improved their access to reindeer teams but involved traveling day and night. The route to Yakutsk went over Tukulan Pass with a spectacular, precipitous descent into the valley of the Aldan River. At the foot of the pass they switched to horse sleighs and proceeded to Yakutsk. They arrived in Yakutsk January 16. Swenson was held up in Yakutsk four days due to visa problems and then proceeded to Irkutsk, arriving February 9. A dispatch from Moscow to the New York Times, datelined March 5, reports his trip. The entire trek amounted to over 4,300 miles (6,900 km).[49][n 6]

The New York Times dispatch also disclosed plans for airplane service between Alaska and the Siberian coast, for which Swenson had just secured permission from the Soviet government. These plans were soon realized when Noel Wien flew $150,000 in furs from the Elisif on March 8. Three further flights were planned but the Soviet government withdrew permission.[50][51][52]

Eielson plane crash near North Cape

The Nanuk was frozen in for the winter of 1929-30 at North Cape, with Swenson and his 17-year-old daughter Marion aboard. Swenson contracted with Alaskan Airways, headed by the noted arctic flyer and explorer Carl Ben Eielson, to fly out furs and crew members. After one successful round trip, Eielson was delayed by a search for a downed plane in Alaska. Resuming after the delay, Eielson and his mechanic Frank Borland flew into a fierce storm over the Siberian coast and crashed, flying into terrain with the throttle wide open. A faulty altimeter may have been a contributing factor. A major search ensued, using both aircraft (American, Canadian, and Soviet) and dogsleds. The fate of both the plane and the ship (with a high-school girl aboard) captured the public's imagination. The New York Times arranged for Marion Swenson to send regular dispatches on the progress of the search.[53] The downed plane was found January 24, 1930, by Joe Crossan and Harold Gillam,[54] and the first body was discovered February 13 by Soviet searchers from the ship Stavropol, Mavriky Slepnyov, and Joe Crossan. Gillam arrived in the evening and identified Borland.[55] Four days later the body of Eielson was found. Swenson and his daughter were flown out February 7 by T.M. (Pat) Reid. The Nanuk returned successfully to Nome and then Seattle, arriving in early August 1930.[56][n 7]

Sled dogs

Swenson is sometimes erroneously credited with introducing the Siberian Husky to the United States. He was an enthusiastic dogsledder who regularly used sled dogs in his work and made at least two long treks. He wrote about selecting dogs for enthusiasm and stamina and about the characteristics of a good lead dog. It is not clear whether Swenson's favorite lead dog Billkoff ever reached the United States. There were Siberian sled dogs in Alaska since 1908 and the early importers are known. Swenson imported Chukchi dogs for Leonhard Seppala in 1927 and for Seppala's collaborator Elizabeth (Peg) Ricker in 1930. These dogs are believed to have been the last Siberian sled dogs exported for many years. The Ricker dogs were used a working team by the crew of the Nanuk in 1929-30.[58][59]

Death

Swenson died August 23, 1938 (age 54) in Seattle of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. The reports in the New York Times and the Polar Times mentioned the possibility of an accident while cleaning the newly purchased gun.[60][61][62]

Writings

Four short nonfiction pieces by Olaf Swenson in Blue Book magazine 1938-39 are listed in a web database.[63]

Northwest of the World was published by Dodd Mead, New York, in 1944. An English edition with different pagination was published by Hale, London in 1951. A French edition was published under the title Au Pays du Renard Blanc in 1953 and 1957. There were also Swedish and Norwegian editions. The book has been cited by historians of Siberia and Alaska.[1][41][64][n 8]

Notes and references

- Notes

- Amelia was identified from Olaf Swenson's death certificate. Ole and Sophia Petersen and their children, including Amelia, age 17, appear in the 1880 census for Manistee. Oluf [sic] and Sven Swenson are listed as resident in the household in 1900. The family had emigrated from Norway. Sophie Peterson is mentioned as great-grandmother of Marion Swenson (Olaf's daughter) in a story about Marion's wedding.[3]

- Anadyr is the name of a gulf of the Bering Sea on the Siberian coast, of the Anadyr River flowing into the gulf, of its estuary (also called Anadyrski Limon in Russian sources and Anadyr Bay in some older English-language sources) and of a small city on the estuary. Anadyr can also refer to an administrative district of Russia established 1889. Although the city did not officially acquire the name until 1923, it occurs in earlier sources. See for instance Forsyth, Stephan, West. Swenson may be using the term to refer to the region rather than the city. The location of the trading station is discussed later in the section. According to the San Francisco Call, the ship dispatched to transport the party was the schooner Abler which then provided transport to Oscar Iden-Zeller; the initial report in the Call from August 8 said the schooner Alice was sent.[9]

- Swenson writes that it was his policy not to carry or trade alcohol because "natives and alcohol do not go well together." He tells two anecdotes related to the absence of alcohol, one from the Anadyr days and one from the north coast during the Soviet days.[25] Alcohol sale was one of the complaints against the Northeastern Siberian Company leading to the loss of its concession.[1] Material in Crow et al. indicates that alcohol sales were handled off-the-books in at least one Northeastern Siberian Company station to preserve deniability, and prompted objections to company management from some of their personnel who did not realize the sales were on the company's behalf. Since Swenson was an independent contractor rather than an employee he may have been able to set his own policy.

- The OCR transcription of the Fairbanks Times account reads Turnei River. This probably originally read Turner, an old name for the Kongakut. Likewise the mention of the "Salmon River" may refer to the Sheenjek River. Swenson's mention of Lake Chandler (Chandlar Lake in the Fairbanks Times story) may be to Chandalar Lake; it clearly does not refer to the lake west of Anaktuvuk Pass.

- Swenson discusses two American trading vessels operating on Siberian rivers. The schooner Nome was in Srednekolymsk when Swenson passed through in 1928, having ascended part of the Indigirka the previous year, at least as far as the village of Russky Ust (Russkoye Ustye) in the delta. The Polar Bear was reported to be in Yakutsk (on the Lena River), having previously been aground in the Kolyma since 1920 until it was freed by local Kolymchanians digging a canal for the purpose.[45][46] (Captain Sigard K. Gudmundson, probably the "Chris Gudmansen" who Swenson reports grounded the Polar Bear by going too far upriver at high water, held a Soviet concession for fur trading in the Kolyma district from 1921.)[47]

- Durany's dates in the New York Times account are a little earlier than Swenson's. This section follows Swenson except for the Irkutsk arrival which Swenson does not date. Swenson thought that this trip had not been done previously (at least in a single winter), an opinion he formed by asking people he encountered on the way whether they had heard of a similar effort. However, at least four American and European parties made slightly longer journeys over the same or similar routes. Two parties from the USS Rodgers traveled basically the same route from Cape Serdze-Kamen to Srednekolymsk and then Verkhoyansk, one proceeding from there to the Lena delta in search of the Jeanette expedition survivors. Both then returned to the US via Verkhoyansk, Yakutsk and Irkutsk. The later part of their journey was made in the summer and included riverboat travel. Harry de Windt and Oscar Iden-Zeller made comparable journeys in the reverse direction.

- The Nanuk was subsequently chartered, and then sold, to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and appeared in at least three motion pictures.[57]

- Northwest of the World includes material on the Chukchi people (Swenson writes Chuckcho) of northeastern Siberia, including observations on clothing, food, tobacco pipes, shelter, hospitality, religion, funeral customs, euthanasia, sexuality, family structure, child rearing, sports, trading practices, distinction between coastal and inland Chuckchi, and property rights in hunting. Other native peoples are discussed more briefly, including the Karakee (presumably Kereks) (houses, dog training, craftsmanship), Lamuts (Even) (clothing, humor), Yukaghir (decimation by epidemic), and Yakuts (houses, reindeer driving, the samma strekla [a triggered bow with a trip-wire, used for hunting; a menace to unwary travelers], sociability, cattle, historical tradition of entry into northeastern Siberia in response to Cossack incursions). There is also material on relations with Tsarist and Soviet authorities, some events and personalities of the Russian civil war, descriptions of walrus hunting and other hunting and trapping practices, several good bear stories, and the aftermath of the 1923 ice tsunami at Ust Kamchatka. The material is often told in anecdotal fashion or flashback and it is sometimes difficult to establish location or chronology. Names are sometimes spelled phonetically, and places on the coast often have English names current among Pacific seamen of the period.[65]

- References

- Owen

- Swenson pp 1-2,4,241; Washington Digital Archives a.

- US Census 1880 and 1900 Manistee, Michigan, Spokane Daily Chronicle

- Swenson pp 6-12; New York Times July 28, 1902, October 30, 1903; Deseret News, Oct 29, 1903

- Swenson p 13

- Washington Digital Archives a, c

- Swenson p 127

- Swenson pp 255-259; Census Seattle 1930, Washington Digital Archives b; Associated Press; New York Times, March 9, 1930

- San Francisco Call, August 8 and Dec 24, 1905

- Crow et al.; Hanford; Bureau of Navigation; Swenson pp 13-17

- Hanford; Lofgren; Swenson pp 17-18

- Swenson pp 74-76, 86

- Hunt 1975 pp 262-264, Crow

- West p 136.

- Swenson p 23

- Swenson pp 27-28, 77-78, 90-91

- Swenson pp 90-91

- Swenson pp 91,163

- Swenson p 91

- New York Times March 13, 1916; Fur Trade Review

- Bergman

- Swenson p 165

- Letter of E.A. Minkin, head of the Commission of Concessions, quoted by Crow et al.

- Swenson pp 162-163 and various locations

- Swenson pp 179-182

- New York Times June 22, 1920, Gay, P. Gray

- Swenson pp 154,158

- Swenson pp 158-160

- Swenson pp 155-162

- Fur Trade Review; Hanford; Marine Review

- New York Times, June 20, 1923; June 21, 1923

- Prescott (AZ) Evening Courier Oct 31, 1923

- Swenson pp 163, 160, 164-167, 171-173, 162-163; New York Times July 31, 1923; Forsyth p 264; Stephan p 166; Saul pp104-105

- Swenson p 267

- Minerals management Service b.

- Swenson pp127-144

- Swenson p143

- Tacoma Public Library (c)

- Swenson p 256; New York Times August 14, 1929; Gleason

- Tacoma Public Library a.; Minerals Management Service a.; Swenson pp100-117; Fairbanks Daily Times

- Hunt (1986)

- Swenson pp 118-126; Hunt (1986); McConnell; Boston Evening Transcript; Bartlett; Cochran; McKinlay; Mills; Niven

- Tacoma Public Library b.

- Swenson pp 177-178,192

- Swenson pp231-234, 236-237

- Gray

- New York Times July 24, 1921

- Swenson pp 193-230, 234-239

- Swenson pp 239-254; Durany

- Szurovy

- Harkey, Ira (1991). Pioneer Bush Pilot. Bantam Books. pp. 265–277. ISBN 0553289195.

- Rearden, Jim (2009). Alaska's First Bush Pilots, 1923-30. Missoula: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 62–84. ISBN 9781575101477.

- Swenson pp255-266; Swenson, Marion; Thrapp

- Swenson, Marion

- Slepnyov; Negenblya

- Gleason

- Tacoma Public Library (d); Gleason

- Swenson pp 182-189

- Thomas

- Washington Digital Archives a

- New York Times, August 25, 1938

- The Polar Times

- Galactic

- Forsyth; Jones; Stephan; Tichotsky

- Swenson, various locations

Sources

- Associated Press. "Home From the Arctic Wastes" Photograph showing Olaf and Marion Swenson being greeted by family members on their return from the Arctic; the caption identifies Mrs. Swenson and Marion's younger sister Marguery (in some papers including the New London Day, Mar 6, 1930 p 16) or Margery (in the Hartford Courant Mar 6, 1930 p3).

- Bartlett, Robert A. and Hale, Ralph T. (1916) The last voyage of the Karluk : flagship of Vilhjalmar Stefansson's Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913-16 McClelland, Toronto pp 312–323. accessed April 29, 2009.

- Bergman, Sten. (1927) Through Kamchatka by Dog Sled and Skis, London, Seeley, Service & Co., 1927 p 106. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c005358112&seq=9

- Boston Evening Transcript Sept 1, 1914, p 7. "Fails to get Karluk crew. Cutter Bear runs short of coal and is returning to Nome."

- Bureau of Navigation, US Dept. of Commerce. Annual list of merchant vessels of the United States Loss of American Vessels Reported during Fiscal Year 1906, p 385.

- Cochran, C.S. (1915). "Report of northern cruise, Coast Guard cutter Bear". Annual report of the United States Coast Guard. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 79–86.

- Crow, John, Anastasia Yarzuktina, and Oksana Kolomiets "American traders and the native people of Chukotka in the early 20th Century" 2010 International Conference on Russian America, Sitka, AK August 18–22.

- Deseret News, Oct 29, 1903 "Prospectors return from northeastern Siberia and report favorably on its minerals".

- Duranty, Walter (1929) "Travels 4,375 miles in coldest Siberia" New York Times March 6 p 6. accessed May 2, 2009.

- Fairbanks Daily Times Nov 16, 1913 p 4 "Two Traders Return from Arctic and Report Fears That Are Felt for Steamship Karluk" (OCR text; image requires registration.)

- Forsyth, James (1994) A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990. Cambridge University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-521-47771-9

- Fur Trade Review 49 (8) May 1922 New Siberian-American trading company formed pp 126–128

- Galactic Central magazine database accessed April 2009, May 2011, November 2016. This link goes out of date periodically as the database grows; see Swenson, Olaf in the site's author index.

- Gay, James Thomas. "Some Observations of Eastern Siberia, 1922" The Slavonic and East European Review 54 (2) 1976, pp. 248–261

- Gleason, Robert J. Icebound in the Siberian Arctic: The Story of the Last Cruise of the Fur Schooner Nanuk and the International Search for Famous Arctic Pilot Carl Ben Eielson Alaska Northwest Pub. Co., 1977 ISBN 978-0-88240-067-9

- Gray, David. Canada's little arctic navy. The ships of the CAE. Canadian Museum of Civilization

- Gray, Patty A. The Predicament of Chukotka's Indigenous Movement: Post-Soviet Activism in the Russian Far North Cambridge University Press, 2005 pp 88–90

- Hanford, Cornelius Holgate (1924) Seattle and environs, 1852–1924, v. 3 Pioneer Historical Pub. Co., 1924, p 541.

- Hunt, William R. (1986) Stef: A Biography of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Canadian Arctic Explorer University of British Columbia Press, 1986 ISBN 0-7748-0247-2 accessed May 3, 2009.

- Hunt, William R. (1975) Arctic Passage. The Turbulent History of the Land and People of the Bering Sea 1697-1975. Charles Scribner's Sons, NY.

- Jones, Preston (2007) Empire's Edge: American Society in Nome, Alaska, 1898-1934. University of Alaska Press, 2007 ISBN 1-889963-89-5

- Lofgren, Svante (1947) "Some Swedish business pioneers in Washington Yearbook American Swedish Historical Museum p65.

- Marine Review v 52 May 1922 "From the Northwest" p 222

- McConnell, Burt M. (1914) "Got Karluck's men as hope was dim", New York Times September 15 p 7. accessed April 29, 2009.

- McKinlay, William Laird (1999) The last voyage of the Karluk: a Survivor's Memoir of Arctic Disaster Macmillan ISBN 0-312-20655-0.

- Mills, William James (2003) Exploring Polar Frontiers: a Historical Encyclopedia ABC-CLIO, 2003 ISBN 1-57607-422-6 "Bartlett, Bob" pp67–70. Accessed April 29, 2009.

- Minerals Management Service, U.S. Department of Interior. "Shipwrecks off Alaska's coast." accessed April 26, 2009 (a) query Elvira 1913 (b) query Kamchatka 1921 Updated link:Shipwrecks off Alaska's Coast

- Negenblya I.E. Above the Arctic limitless. Yakutsk. 1997. pp. 157–159

- New York Times, July 28, 1902, "To mine gold in Siberia" p 1

- New York Times, October 30, 1903. "Siberian mineral wealth" p 1

- New York Times, March 13, 1916 "Goes to meet Stefansson; Captain Olaf Swenson will do some hunting in the arctic" p 3.

- New York Times, June 22, 1920 "Trade post looter known. Mikoff, Reputed Leader of Anadyr Rising ..." p 7.

- New York Times, July 24, 1921 "Gets fur concessions; American Skipper Says Siberian Soviet Government Has Granted Them" p2

- New York Times, June 20, 1923 "3 American ships seized by Soviets"

- New York Times, June 21, 1923 "Ships Soviets seized had liquor cargoes" p 30.

- New York Times, July 31, 1923 "Report cruelty in Siberia; Crew of Released American..."

- New York Times, August 14, 1929 "Crew taken off wrecked schooner" p47.

- New York Times, March 9, 1930 "Tragedy of the arctic snows" (photo section; one photo shows Marion Swenson with her parents and sister).

- New York Times, January 9, 1931 "Captain Jochimsen, arctic hero, dead" p 20. accessed April 29, 2009.

- New York Times, August 25, 1938 "Arctic trader shot dead" p5.

- Niven, Jennifer (2001) The Ice Master: The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk. Hyperion, ISBN 0-7868-8446-0, pp336–350. accessed May 2, 2009

- Owen, Thomas C. (2008) "Chukchi gold: American enterprise and Russian xenophobia in the Northeastern Siberia Company". Pacific Historical Review 77 (1), pp 49–85.

- Prescot [AZ] Evening Courier Oct 31, 1923 "Last of Russ White forces are defeated" p 1.

- San Francisco Call "Schooner hits a reef in fog" August 8, 1905, p 5

- San Francisco Call "Tramps through the snows of bleak siberia" December 24, 1905 p8

- Saul, Norman E. (2006) Friends or foes?: the United States and Soviet Russia, 1921-1941 University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-1448-6 pp104–105

- Slepnyov M.T. "Tragedy in Long Strait" Soviet Arctic (Moscow). 1937. p.10

- Stephan, John J. (1996) The Russian Far East: A History Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2701-5, ISBN 978-0-8047-2701-3 p 168

- Szurovy, Géza (2004) Bushplanes Zenith Press (MBI Publishing) St. Paul, MN.

- Swenson, Olaf (1944) Northwest of the World. Dodd Mead, NY online edition at Hathi Trust

- Swenson, Marion "Eielson's throttle found wide open; height misjudged" New York Times January 28, 1930.

- Spokane Daily Chronicle, Nov. 15, 1937 "Miss Swenson wed Thursday" mentions great-grandmother Sophie Peterson.

- Tacoma Public Library (a), "Ships and Shipping Database"; query Elvira accessed April 28, 2009. This source quotes Gordon Newell, "Maritime Events of 1913," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, p. 230.

- Tacoma Public Library (b), "Ships and Shipping Database"; query King & Winge accessed April 29, 2009. This source quotes Gordon Newell, "Maritime Events of 1914," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, pp 242–3.

- Tacoma Public Library (c), "Ships and Shipping Database"; query Elisif accessed April 30, 2009. This source quotes Gordon Newell, "Maritime Events of 1929-1930," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, p. 403.

- Tacoma Public Library (d), "Ships and Shipping Database"; query Nanuk accessed April 30, 2009. This source quotes Gordon Newell, "Maritime Events of 1933," H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, p. 423.

- The Polar Times October 1938 p 17 "Swenson, '14 hero of arctic, is found slain"

- Thomas, Bob. (2001) "Where did they come from and what did they look like? Part II" The International Siberian Husky Club, NEWS, September/October.

- Thrapp, Dan L., (1991) "Eielson, Carl Ben(jamin)" Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: A-F, U of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-9418-2, p456.

- Tichotsky, John (2000) Russia's diamond colony: the republic of Sakha Routledge, ISBN 90-5702-420-9 p 72

- United States Census 1880, 1900, Manistee, Michigan at Familysearch.org

- Washington digital archives. http://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov/ (a) query Washington death records, Olaf Swenson, 1938. (b) query Washington death records, Marion Ferguson, 1951. Accessed April 10, 2009. (c) query King County marriage records, Olaf Swenson, 1904, accessed Jan 21, 2010. (d) query marriage records under "Detailed Search" Thomas Ferguson, Marion Swenson; accessed March 1, 2013. Wedding was Nov. 11, 1937 and Marjorie Swenson was a witness.

- West, Ellsworth Luce (1965) as told to Eleanor Ransom Mayhew. Captain's papers: a log of whaling and other sea experiences; Barre Publishers, Barre, MA

Further reading

- Yarzutkina, Anastasia A. Trade on_the_Icy_Coasts. The management of_American traders in the settlements of Chukotka Native Inhabitants. Terra Sebus: Acta Musei Sabesiensis Special issue. Russian Studies. From the early Middle Ages to the Present Day. Sorin Armire, Cristian Ioan Popa, Maxim Trushin, eds. 2014, pp. 361-381

- Sablin, Ivan. Interactions and Elites in Late Pre-Soviet and Early Soviet Chukotka, 1900–1931 Social Evolution & History. 12(1) March 2013 (not a direct link; search title)

- Rytkheu, Yuri, trans. by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse (fiction) A Dream in Polar Fog (Archipelago Books, 2006). ISBN 978-0-9778576-1-6

- Crichton, Clarke. Frozen-in! (Putnam, 1930) account of the 1929-30 voyage of the Nanuk

- Swenson, Olaf. Northwest of the world; forty years trading and hunting in northern Siberia (Dodd, Mead & Company, 1944 )

External links

- Alaska archives photo of Marion and Olaf Swenson, North Cape, 1930 The accompanying caption lists this as March 1930 but it is either earlier or not at North Cape or both. The New York Times has Marion Swenson back in Seattle March 1.

- Maps useful in identifying locations in Northwest of the World: